Triumph and Tragedy in Mudville (25 page)

Read Triumph and Tragedy in Mudville Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

The Shot Heard ’Round the World: The New York Giants swarm Bobby Thomson after his three-run, ninth-inning home run beats the Brooklyn Dodgers—and wins the Giants the National League title—at the Polo Grounds on October 3, 1951.

Credit: Bettmann/Corbis

To this day, I can never adequately describe the feeling that went through me as I circled the bases…. I can remember feeling as if time was just frozen. It was a delirious, delicious moment and when my feet finally touched home plate and I saw my teammates’ faces, that’s when I realized I had won the pennant with one swing of the bat. And I’d be a liar if I didn’t admit that I’ll cherish that moment till the day I die.

Janus has two faces because we need to look both ways toward transcendence and reality—somehow titrating both to forge a reasonable approach to life. As Bucky (Fuller, not Dent of the glorious 1978 home run) said: “Unity is plural and, at minimum, is two.” And as Amos (the prophet, not Rusie the Hall of Fame pitcher) proclaimed (Amos 3:3): “Can two walk together, except they be agreed?”

Books reviewed:

A Whole Different Ball Game: The Sport and Business of Baseball

by Marvin Miller

Ted Williams: A Portrait in Words and Pictures,

edited by Dick Johnson, text by Glenn Stout

My Favorite Summer, 1956

by Mickey Mantle and Phil Pepe

The Home Run Heard ’Round the World: The Dramatic Story of the 1951 Giants-Dodgers Pennant Rac

e by Ray Robinson

Reprinted with permission from the

New York Review of Books

. Copyright © 1991 NYREV, Inc. First published October 24, 1991.

I

f you wish to divide Americans into two unambiguous groups, what would you choose as the best criterion? Males and females, east and west of the Mississippi? May I suggest, instead, the following question: “What was Justice Blackmun’s worst decision?” Anti-abortionists, and conservatives in general, will reply without a moment’s hesitation:

Roe

v.

Wade

. Liberals might need to think for a moment, but if they like baseball as well, they will surely answer:

Flood

v.

Kuhn

. For, in 1972, the same Harry Blackmun who gave us

Roe

v.

Wade

also wrote the 5–3 decision (with the usual trio of Douglas, Marshall, and Brennan in opposition) denying outfielder Curt Flood the right to negotiate freely with other teams following the expiration of his contract with the St. Louis Cardinals, and upholding the admittedly illogical exemption of major league baseball from all antitrust legislation (on the preposterous argument that this game alone—for none other enjoys such a waiver—is a sport and not a business).

Curt Flood was one of the best ballplayers of the 1960s, a fine outfielder with a nearly .300 lifetime batting average. Following the 1969 season, after twelve good years with the Cards, he was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies—and he didn’t want to go (or at least he wanted the option, available to any free man, of placing his services on the market and negotiating with other teams). But major league baseball, by explicit judicial sanction, had always enforced a system of peonage based upon the reserve clause. This statement, present in all contracts, “reserved” the player’s services to his club for the following season, even if terms had not been reached on a new contract. (That is, the player could be “reappointed”—without his approval, take it or leave it—for a following year at the same terms as the last season.) In effect, the reserve clause provided a perpetual contract because owners granted themselves the power of indefinite extension, year after year. Thus, teams owned players and could pay and trade them almost at will. A player had but one “recourse,” really a death warrant, rather than a weapon: he could refuse to sign, but to what avail? No other team would hire him.

Owners insisted that they needed such a provision to prevent baseball’s wreckage by bidding wars—an odd argument that management must be protected from itself by oppressing workers. In two previous rulings, in 1922 and 1953, the Supreme Court had upheld baseball’s exemption from antitrust legislation, thereby depriving players of any judicial remedy for abuses of the reserve clause. (The Court did not present a constitutional defense of management, but rather passed the buck, stating that any regulation of baseball’s traditional ways must be instituted by Congress.) Blackmun’s regrettable decision of 1972 includes a mixture of platitudes about the sanctity of our national pastime, combined with a third passing of the buck.

All Americans not

living in a hole know that circumstances have since reversed dramatically: the reserve clause is history and players now have adequate power and fair representation in negotiating contracts. Consequently, players are coequal with management, and their gargantuan salaries hog more news than their accomplishments on the field. (I don’t want to bore you with figures so endlessly repeated in the press that they have become a litany.)

Two other points are equally obvious to all fair-minded observers, but not so frequently stressed. First, contrary to the doomsday predictions made by owners for more than a century, baseball remains in good health. Owners insisted that free agency would lead to an unfair concentration of talent, but free bidding has increased interest and competition on the field by reducing the differences among teams and giving most a chance for a championship. Between 1949 and 1964 a New York team played in the World Series in all years but 1959. The Yankees alone won nine World Series during this period. These were blissful years for a Yankee fan like me, but not good for baseball and the rest of the country. No such dynasties exist today; talent is too mobile and this year’s last can become next season’s first.

Second, effective unionizing of players had produced this more equable distribution of baseball’s immense revenues. (The vast increase arises from TV and radio contracts, and remarkably effective merchandizing—but owners wouldn’t have shared the bounty voluntarily.) I doubt that a better success story for trade unionism can be told in our times. Dave Winfield, a great veteran player and one of the most thoughtful men in the game today, said it all: “I have been a part of the best union for workers in this country. I don’t think that baseball players have been greedy, or that the union has been greedy or nasty. The owners used to make all the money. Now they share it.”

As much as traditional trade unionists may take heart from this success, special circumstances prohibit a translation into more conventional workplaces. We are, after all, speaking of a few hundred “workers” (major league players) in a market that brings in billions of dollars a year for the exercise of their talents. The average person in an office or on an assembly line simply cannot generate such resources for potential sharing. As Gene Orza, general counsel of the Players Association, once said to me: “Workers vs. bosses just can’t be the rhetoric any more. I would rather talk of playing capitalists vs. entrepreneurial capitalists.”

I do not

generally believe in “great man” theories of history, but I cannot think of a better case for the importance of a single person. The Players Association owes its success to good sense and good fortune in not hiring a management shill to lead a nascent association that would have become a company club (the previous history of players’ “unions”), but in bucking baseball’s “in-house” tradition and appointing Marvin Miller, lifelong trade union professional, chief economist for the United Steelworkers of America, and a brilliant, persistent, patient, and principled man (also an old Dodger fan from a Brooklyn boyhood).

Miller, who created an effective union out of the Players Association and served as its executive director from the mid-sixties to the early eighties, has finally written his long-awaited account:

A Whole Different Ball Game: The Sport and Business of Baseball

. The jacket copy by the great announcer Red Barber (voice of the hated Bums and later the beloved Yanks in my youth) states with all the one-sided strength of the genre, but with undeniable justice and accuracy:

When you speak of Babe Ruth, he is one of the two men, in my opinion, who changed baseball the most. He changed the construction of the game, the construction of bats as well as the ball. And the second most influential man in the history of baseball is Marvin Miller…. Miller formed the players’ union. And from the union we have free agency, we have arbitration. We have the entire structure of baseball changed—the entire relationship between the players and the owners.

If we ask how such a radical change could occur so quickly, two factors stand out. (Though we should, following recent events in the former Soviet Union, recognize that complex systems, when they change at all, tend to transform by rupture rather than imperceptible evolution.) First, the new revenues of our TV culture provided a gargantuan pie to divide; no matter how much power players gained, they could not have achieved their current economic might from gate receipts. Second, players had to start very far down in order to rise so far—and we must ask why they were so oppressed (or, rather, “underempowered,” if oppressed seems too strong a word for stars in the entertainment industry, whatever their exploitation).

Why, then, did

players have so little power in the pre-Miller era? Why were they so underpaid, so devoid of influence over their own lives and futures? Why could the owner’s pawn, first commissioner of baseball Kenesaw Mountain Landis, ban Shoeless Joe Jackson and the seven other Black Sox for life—without trial and without any hope of redress—after a court had dismissed charges against them of throwing the World Series? Why did the stigma stick so strongly, and permanently, to yield this, the most poignant of all baseball stories: Jackson ended up behind the counter of a liquor store in his native South Carolina. One day, more than thirty-five years after the Black Sox scandal, Ty Cobb stopped by. Cobb brought some bottles to the register, but Jackson just looked down, said nothing, and began to ring up the transaction. The puzzled Cobb exclaimed: “Joe, don’t you recognize me?” “Of course I do, Ty,” Jackson replied, “but I wasn’t sure you wanted to know me.” (Only Cobb and Rogers Hornsby had lifetime batting averages higher than Jackson’s. Cobb himself was widely suspected, probably correctly, of consorting with gamblers and occasionally throwing games.)

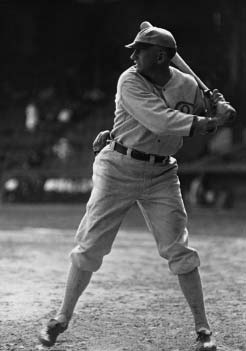

Shoeless Joe Jackson, circa 1919.

Credit: Corbis

The reasons for this underempowerment are complex, but consider two intertwined aspects. Owners played an effective game of “divide and conquer” against a group of mostly young and uneducated players (Rube, the nickname of so many early players, reflected a common background). Hardly any of the early players went to college and few finished high school. Baseball, for all the mythological hyping, really took root as a people’s sport in America, while football remained a minor pastime for a collegiate elite. Owners nipped any fledgling attempts at organization among players by providing a few paternalistic scraps and then invoking the same bogeymen that stalled unionization in more fertile fields of factories and mines—“not real baseball people,” “trying to undermine the game,” “radicals,” “outside agitators.” A grizzled miner with twenty years in the pits, a huge debt at the company store, and thousands of compatriots might see through the bluff; an eighteen-year-old farmboy, with no one to represent him and only a few hundred colleagues, might never think of mounting a challenge. Moreover, owners had great success in invoking the hoary and elaborate mythology of baseball as a “game” and a “national pastime”—the same line that the Supreme Court has bought three times. “How can you even raise a question about salaries?” owners would intone: “Where else could a person actually get paid for playing a game? Thank your lucky stars, shut up, play, and don’t complain.” The ruse worked for nearly one hundred years.

This interplay of baseball’s sporting mythology and its commercial reality fascinates me more than anything else about the game as a social phenomenon in America. Each year’s flood of baseball books can be neatly partitioned into these two basic categories. I shall call them H-mode and Q-mode, for hagiographical and quotidian reality. Such a division seems especially well marked in this season of anniversaries. Miller tells us that he chose this year to publish (in Q-mode) because he wished to launch his book on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the founding of the Players Association in 1966. As for the H-mode, you would have to live in the same hole previously mentioned not to know that 1991 is the fiftieth anniversary for the greatest achievements of two baseball saints—Joe DiMaggio’s fifty-six-game hitting streak and Ted Williams’s .406 batting average (no one has exceeded .390 since then). The

New York Times

has run a box in every issue this season detailing Joe and Ted’s daily accomplishments in 1941. President Bush invited DiMaggio and Williams to the White House on July 9, and then flew them, with baseball commissioner Fay Vincent, up to Toronto aboard Air Force 1 to take in the sixty-second All-Star Game. Bush, who had entertained Elizabeth II in Washington just a few days before, stated: “I didn’t think I’d get to meet royalty so soon after the queen’s visit.”

I will therefore

devote this year’s World Series–time review of baseball books to a contrast of the H-and Q-modes, in particular to a comparison of Miller’s anniversary with books devoted to three milestones in the hagiographical tradition—the story of a career (Ted Williams on the fiftieth anniversary of his greatest achievement), a season (Mickey Mantle’s favorite 1956 campaign on its thirty-fifth anniversary), and even of an incident (Bobby Thomson’s most famous of all home runs, on the fortieth anniversary of its few-second trajectory from bat to the left-field seats). (The mills of the gods may grind exceedingly fine but the microscope of hagiography probes even more minutely.) I may also cite another, and more immediate, reason for choosing to contrast Miller’s book with three different representatives of the hagiographical tradition. The existence of the myth—particularly its unfair, but clever exploitation by owners—made Marvin Miller necessary.