Triumph and Tragedy in Mudville (22 page)

Read Triumph and Tragedy in Mudville Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

“But for this” must therefore drive the tale of Bill Buckner’s legs into the only version that can validate the canonical story. In short, poor Bill must become the one and only cause and focus of ultimate defeat or victory. That is, if Buckner fields the ball properly, the Sox win their first World Series since 1918 and eradicate the curse of the Bambino. But if Buckner bobbles the ball, the Mets win the Series instead, and the curse continues in an even more intense and painful way. For Buckner’s miscue marks the unkindest bounce of all, the most improbable, trivial little error sustained by a good and admired man. What hath God wrought?

Except that Buckner’s error did

not

determine the outcome of the World Series for one little reason, detailed above but all too easily forgotten. When Wilson’s grounder bounced between Buckner’s legs, the score was already tied! (Not to mention that this game was the sixth and, at worst for the Sox, the penultimate game of the Series, not the seventh and necessarily final contest. The Sox could always have won game seven and the entire Series, no matter how the negotiations of God and Satan had proceeded over Bill Buckner as the modern incarnation of Job in game six.) If Buckner had fielded the ball cleanly, the Sox would not have won the Series at that moment. They would only have secured the opportunity to do so, if their hitters came through in extra innings.

We can easily excuse any patriotic American who is not a professional historian, or any casual visitor for that matter, for buying into the canonical story of the Alamo—all the brothers were valiant—and not learning that a healthy and practical Bowie might have negotiated an honorable surrender at no great cost to the Texian cause. After all, the last potential eyewitness has been underground for well over a century. We have no records beyond the written reports, and historians cannot trust the account of any eyewitness, for the supposed observations fall into a mire of contradiction, recrimination, self-interest, aggrandizement, and that quintessentially human propensity for spinning a tall tale.

But any baseball fan with the legal right to sit in a bar and argue the issues over a mug of the house product should be able to recall the uncomplicated and truly indisputable facts of Bill Buckner’s case with no trouble at all, and often with the force of eyewitness memory, either exulting in impossibly fortuitous joy, or groaning in the agony of despair and utter disbelief, before a television set. (To fess up, I should have been at a fancy dinner in Washington, but I “got sick” instead and stayed in my hotel room. In retrospect, I should not have stood in bed.)

The subject attracted my strong interest because, within a year after the actual event, I began to note a pattern in the endless commentaries that have hardly abated, even fifteen years later—for Buckner’s tale can be made relevant by analogy to almost any misfortune under a writer’s current examination, and Lord only knows we experience no shortage of available sources for pain. Many stories reported, and continue to report, the events accurately—and why not, for the actual tale packs sufficient punch, and any fan should be able to extract the correct account directly from living and active memory. But I began to note that a substantial percentage of reports had subtly, and quite unconsciously I’m sure, driven the actual events into a particular false version—the pure “end member” of ultimate tragedy demanded by the canonical story “but for this.”

I keep a growing file of false reports, all driven by requirements of the canonical story—the claim that, but for Buckner’s legs, the Sox would have won the Series, forgetting the inconvenient complexity of a tied score at Buckner’s ignominious moment, and sometimes even forgetting that the Series still had another game to run. This misconstruction appears promiscuously, both in hurried daily journalism and in rarefied books by the motley crew of poets and other assorted intellectuals who love to treat baseball as a metaphor for anything else of importance in human life or the history of the universe. (I have written to several folks who made this error, and they have all responded honorably with a statement like: “Omigod, what a jerk I am! Of course the score was tied. Jeez [sometimes bolstered by an invocation of Mary and Joseph as well], I just forgot!”)

For example, a front-page story in

USA Today

for October 25, 1993, discussed Mitch Williams’s antics in the 1993 Series in largely unfair comparison with the hapless and blameless Bill Buckner:

Williams may bump Bill Buckner from atop the goat list, at least for now. Buckner endured his nightmare Oct. 25,1986. His Boston Red Sox were one out away from their first World Series title since 1918 when he let Mookie Wilson’s grounder slip through his legs.

Or this from a list of Sox misfortunes, published in the

New York Post

on October 13, 1999, just before the Sox met the Yanks (and lost of course) in their first full series of postseason play:

Mookie Wilson’s grounder that rolled through the legs of Bill Buckner in Game 6 of the 1986 World Series. That happened after the Red Sox were just one out away from winning the World Series.

For a more poetic view between hard covers, consider the very last line of a lovely essay written by a true poet and devoted fan to introduce a beautifully illustrated new edition of the classic poem about failure in baseball,

Casey at the Bat

:

Triumph’s pleasures are intense but brief; failure remains with us forever, a mothering nurturing common humanity. With Casey we all strike out. Although Bill Buckner won a thousand games with his line drives and brilliant fielding, he will endure in our memories in the ninth inning of the sixth game of a World Series, one out to go, as the ball inexplicably, ineluctably, and eternally rolls between his legs.

1

But the nasty little destroyer of lovely canonical stories then pipes up in his less mellifluous tones: “But I don’t know how many outs would have followed, or who would have won. The Sox had already lost the lead; the score was tied.” Factuality embodies its own form of eloquence; and gritty complexity often presents an even more interesting narrative than the pure and archetypal “end member” version of our canonical stories. But something deep within us drives accurate messiness into the channels of canonical stories, the primary impositions of our minds upon the world.

To any reader who now raises the legitimate issue of why a scientist should write an essay about two stories in American history that bear no evident relevance to any overtly scientific question, I simply restate my opening and general argument: human beings are pattern-seeking, story-telling creatures. These mental propensities generally serve us well enough, but they also, and often, derail our thinking about all kinds of temporal sequences—in the natural world of geological change and the evolution of organisms, as well as in human history—by leading us to cram the real and messy complexity of life into simplistic channels of the few preferred ways that human stories “go.” I call these biased pathways “canonical stories”—and I argue that our preferences for tales about directionality (to explain patterns), generated by motivations of valor (to explain the causal basis of these patterns) have distorted our understanding of a complex reality where different kinds of patterns and different sources of order often predominate.

I chose my two stories on purpose—Bowie’s letter and Buckner’s legs—to illustrate two distinct ways that canonical stories distort our reading of actual patterns: first, in the tale of Jim Bowie’s letter, by relegating important facts to virtual invisibility when they cannot be made to fit the canonical story, even though we do not hide the inconvenient facts themselves, and may even place them on open display (as in Bowie’s letter at the Alamo), and second, in the tale of Bill Buckner’s legs, where we misstate easily remembered and ascertainable facts in predictable ways because these facts did not unfold as the relevant canonical stories dictate.

These common styles of error—hidden in plain sight, and misstated to fit canonical stories—arise as frequently in scientific study as in historical inquiry. To cite, in closing, the obvious examples from our standard misreadings of the history of life, we hide most of nature’s diversity in plain sight when we spin our usual tales about increasing complexity as the central theme and organizing principle of both evolutionary theory and the actual history of life. In so doing, we unfairly privilege the one recent and transient species that has evolved the admittedly remarkable invention of mental power sufficient to ruminate upon such questions.

This silly and parochial bias leaves the dominant and most successful products of evolution hidden in plain sight—the indestructible bacteria that have represented life’s mode (most common design) for all 3.5 billion years of the fossil record (while

Homo sapiens

hasn’t yet endured for even half a million years—and remember that it takes a thousand million to make a single billion). Not to mention that if we confine our attention to multicellular animal life, insects represent about 80 percent of all species, while only a fool would put money on us, rather than them, as probable survivors a billion years hence.

For the second imposition of canonical stories upon different and more complex patterns in the history of life—predictable distortion to validate preferred tales about valor—need I proceed any further than the conventional tales of vertebrate evolution that we all have read since childhood, and that follow our Arthurian mythology about knights of old and men so bold? I almost wince when I find the first appearance of vertebrates on land, or of insects in the air, described as a “conquest,” although this adjective retains pride of place in our popular literature.

And we still seem unable to shuck the image of dinosaurs as born losers vanquished by superior mammals, even though we know that dinosaurs prevailed over mammals for more than 130 million years, starting from day one of mammalian origins. Mammals gained their massively delayed opportunity only when a major extinction, triggered by extraterrestrial impact, removed the dinosaurs—for reasons that we do not fully understand, but that probably bear no sensible relation to any human concept of valor or lack thereof. This cosmic fortuity gave mammals their chance, not because any intrinsic superiority (the natural analog of valor) helped them to weather this cosmic storm, but largely, perhaps, because their small size, a side-consequence of failure to compete with dinosaurs in environments suited for large creatures, gave mammals a lucky break in the form of ecological hiding room to hunker down.

Until we abandon the silly notion that the first amphibians, as conquerors of the land, somehow held more valor, and therefore embody more progress, than the vast majority of fishes that remained successfully in the sea, we will never understand the modalities and complexities of vertebrate evolution. Fish, in any case, encompass more than half of all vertebrate species today, and might well be considered the most persistently successful class of vertebrates. So should we substitute a different canonical story called “there’s no place like home” for the usual tale of conquest on imperialistic models of commercial expansion?

If we must explain the surrounding world by telling stories—and I suspect that our brains do force us into this particular rut—let us at least expand the range of our tales beyond the canonical to the quirky, for then we might learn to appreciate more of the richness out there beyond our pale and usual ken, while still honoring our need to understand in human terms. Robert Frost caught the role and necessity of stories—and the freedom offered by unconventional tales—when he penned one of his brilliant epitomes of deep wisdom for a premature gravestone in 1942:

And were an epitaph to be my story

I’d have a short one ready for my own.

I would have written of me on my stone:

I had a lover’s quarrel with the world.

Books reviewed:

Ball Four Plus Ball Five

by Jim Bouton

Mr. October: The Reggie Jackson Story

by Maury Allen

T

rue innovation carries within itself the seeds of its own obsolescence. Our urges to copy when unimaginative, or to improve and extend when more inspired, convert yesterday’s rebel into today’s ho-hum.

First published in

Washington Post Book World

, June 21, 1981.

Jim Bouton shined during the closing days of the great Yankee dynasty. He won two games in the 1964 World Series, but could not stop the Cardinals and their Gibson machine single-handedly. He pitched so hard that his cap, obeying Newton’s third law, often flew off as his body lunged forward. Mickey Mantle called him the “bulldog.” But his arm went bad and he won only nine games during his last four years as a Yankee. In 1969, he tried to come back as a marginally effective knuckleballer, barely holding on in the bullpen of the hapless Seattle Pilots (now the respectable Milwaukee Brewers), an expansion team that spent its single year of life mired deep in the cellar of the American League West. There he composed

Ball Four

, an honest and irreverent daily account of a baseball season viewed from within and below. Its candor scandalized a profession that expected to keep its secrets and come before the reading public with traditional books about sexless, Coke-drinking, cardboard heroes. Bouton’s book was so successful that honest confession replaced myth-making as a preferred literary genre of the field.

Ten years later, Bouton has reissued

Ball Four

with a forty-page update, inevitably titled

Ball Five

. In rereading classics, I am always struck by the contrast between memory and reality. Many of the famous scenes of

Ball Four

have not lost their impact, but I remembered them as chapters, while they actually appear as paragraphs. Although

Ball Four

does recount the flaky antics of grown men, such as an unbeauty contest conducted to pick Yogi Berra’s successor on the “all-ugly nine” among active players, its real focus is on the anxieties and frustrations of a sore-armed athlete on a third-rate team. Its strength, in retrospect, lies not in its exposés—tame stuff compared with later works modeled upon it, and notoriously silent on race and real sex, while reasonably explicit about drinking and pill popping. Rather its relentless, even tedious, rendition of daily hopes, pettinesses, and pains—why did they yank me, why didn’t they pitch me—displays a human side of sports that we never discern in baseball books of the pre-Bouton era.

Ball Four

is a permanent antidote to the common view that ballplayers are hunks of meat, naturally and effortlessly displaying the talents that nature provided. Excellence in anything is a single-minded struggle, to be valued if only for its rarity. The honest struggles of winners

and

losers are our sustaining hopes for a species mired in mediocrity—whether the struggle be expressed in relentless search for the perfect knuckleball, the holy grail, or the Great American Novel.

Ball Five

recounts Bouton’s last decade as a broadcaster, actor, divorcé, and even comeback pitcher for the Atlanta Braves. It is studded with quotable one-liners. On Billy Martin’s reaction to

Ball Four

(before he wrote his own book in the Boutonian tradition): “Billy Martin…came running across the field hollering for me to get the hell out…. Because I’ve grown accustomed to the shape of my nose, I got the hell out.” On the high salaries that Bouton never enjoyed: “My position is that while the players don’t deserve all that money, the owners don’t deserve it even more.” Still,

Ball Five

is too sketchy to merit purchase on its own strength; for it is only a little less insubstantial than its title. Yet if

Ball Five

served as a vehicle for bringing

Ball Four

back into print, then it has done its part.

Today, Bouton’s book as exposé seems almost quaint in comparison with those that followed. Indeed, we will never again see books in the style of

Lucky to Be a Yankee

, the heroic account of Joe DiMaggio that set such an unrealistic pattern for my own youth. Maury Allen, author of a fine post-Boutonian book on the hero of my childhood (

Where Have You Gone, Joe DiMaggio?

), has now written

Mr. October

, a perfectly adequate, though uninspired, biography of Reggie Jackson.

Mr. October

is a sports book in the old style. It contains much hackneyed writing in the heroic tradition: “Harnessing all the power in his 205-pound twenty-five-year-old body, Jackson exploded in a flash as the ball moved toward the plate.” It tells the heartwarming stories of Reggie’s visits to dying cancer patients, old and young. One picture caption reads: “Reggie has extraordinary demands on his time but always finds time for kids. Here he makes a handicapped lad one happy fellow.” Allen even puts in a good word for George Steinbrenner, citing his charitable contributions to underprivileged kids. It purveys quick and dirty conclusions as profundity—including the psychobabble interpretation of Jackson’s relationship with Billy Martin offered by “a leading Bellevue psychiatrist” who requested anonymity because he had never met either men, but only read about them.

Yet, through all this hasty conventionality,

Mr. October

contains some honestly forthright and controversial material. Its discussions about the sex lives of players on the road is far more extensive than Bouton’s was. Allen’s account of persistent racism at both ends of the hierarchy—how many black owners and utility infielders do you see?—is as serious an indictment of modern baseball as anyone could raise. To make it in the majors, a black man had still better be a star—like Reggie Jackson. It is Jim Bouton’s legacy that even the most ordinary of sports books now outdoes

Ball Four

in candor.

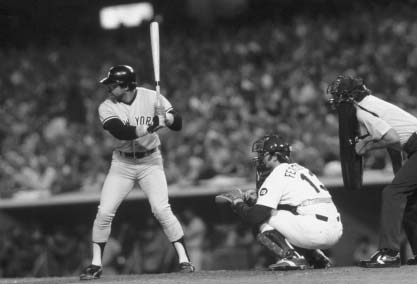

Reggie Jackson, playing for the Yankees, bats against the Los Angeles Dodgers in the 1978 World Series.

Credit: Neil Preston/Corbis

Yet I wonder. Surely we don’t want dishonest books that misrepresent real people. Yet the ballplayer as unadorned hero has a legitimate place in American mythology. To me, Joe DiMaggio looks as elegant selling Mr. Coffee today as he did swinging a bat when I was a kid. As a nation, we are too young to have true mythic heroes, and we must press real human beings into service. Honest Abe Lincoln the legend is quite a different character from Abraham Lincoln the man. And so should they be. And so should both be treasured, as long as they are distinguished. In a complex and confusing world, the perfect clarity of sports provides a focus for legitimate, utterly unambiguous support of disdain. The Dodgers are evil, the Yankees good. They really are, and have been for as long as anyone in my family can remember.

So Reggie, I am happy to know you a bit better as a man. But I will always remember you most for a glorious day in 1977—in October, of course—when you destroyed the enemy with three homers on three pitches. And I’ll keep eating those Reggie bars, even though the taste leaves something to be desired, and even though the Baby Ruth was named for Grover Cleveland’s daughter.