Triumph and Tragedy in Mudville (19 page)

Read Triumph and Tragedy in Mudville Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

I

can only beg indulgence for opening a sporting commentary with the most venerable of professorial conceits: a quotation from the classics. Nearly twenty-five hundred years ago, long before Mr. Doubleday didn’t invent baseball in 1839, Protagoras characterized our lamentable tendency to portray all complex issues as stark dichotomies of us against them: “There are two sides to every question, exactly opposite to each other.”

Often, we highlight these caricatures by pairing the poles of our dichotomies in rhyme or alliteration as well—as in nature vs. nurture for the origin of our behaviors, or brain vs. brawn for the sources of manly success. Strength for the warrior and the athlete; smarts for the scholar and the tycoon.

First published in the

New York Times

, June 25, 2000. Reprinted with permission of the

New York Times.

Discerning sports fans do not carry this dichotomy to the extreme of regarding their athletic heroes as pervasively deficient in mind—as if God gave each person just so much “oomph,” thus requiring that an ounce of intellect be rendered back for each ounce of muscle added on. Rather, we tend to characterize the mental skill of athletes as an intuitive grasp of bodily movement and position, a “physical intelligence,” if you will. Thus, we do recognize a mental component in DiMaggio’s grace, in the beautiful and devastatingly effective motions of Michael Jordan or Muhammad Ali, and even in the sheer force of Shaq pushing through to the basket. (Perhaps no one can stop three hundred pounds of acceleration, but the big man still has to know where he should end up.)

This fallacious belief in the intuitive and physical nature of athletic mentality may best be summarized in the common sports term for a player on a roll of successive triumphs at bat or basket: “He’s unconscious!”

On the other side of the same misconception, we often blame the intrusion of unwanted consciousness when a fine player, after many years of professional success, encounters a glitch in performing the ordinary operations of his trade. Thus, when Chuck Knoblauch “freezes,” and suddenly cannot execute the conventional flip from second to first base, we say that his conscious brain has intruded upon a bodily skill that must be honed by practice into a purely automatic and virtually infallible reflex.

I do not regard this conventional view as entirely wrong, but I do think that, for two major reasons, we seriously undervalue the mental side of athletic achievement when we equate the intellectual aspect of sports with unverbalizable bodily intuition and regard anything overtly conscious as “in the way.”

First, one of the most intriguing, and undeniable, properties of great athletic performance lies in the impossibility of regulating certain central skills by overt mental deliberation: the required action simply doesn’t grant sufficient time for the sequential processing of conscious decisions. The defining paradox, and delicious fascination, of hitting a baseball lies most clearly within this category.

Batters just don’t have enough time to judge a pitch from its initial motion and then to decide whether and how to swing. Batters must “guess,” from the depths of their study and experience, before a pitcher launches his offering; and a bad conjecture can make even the greatest hitters look awfully foolish, as when Pedro Martinez throws his change-up with the exact same arm motion as his fastball, and the batter, guessing heat, has already completed his swing before the ball ever lollygags across the plate.

Indeed, such mental operations cannot proceed consciously and sequentially. But these skills do not therefore become a lesser form of intellect confined to the bodily achievements of athletes. Many of the most abstract and apparently mathematical feats of mind fall into the same puzzling category.

For example, several of history’s greatest mental calculators have been able to specify the algorithms, or rules of calculation, that they claim to use in performing effectively instantaneous feats, like specifying the day of the week for any date in any year, no matter how many centuries past or future. But extensive studies show that these calculators work too quickly to achieve their results by any form of conscious and sequential figuring.

Second, the claim that Knoblauch’s distress arises from the imposition of brain upon feeling (or mind upon matter) represents the worst, and most philistine, of mischaracterizations. Yes, one form of unwanted, conscious mentality may be intruding upon a different and required style of unconscious cognition. But we encounter mentality in either case, not body against mind. Knoblauch’s problem takes the same form as many excruciating impediments in purely mental enterprises with writer’s block as the most obvious example, when obsession with learned rules of style and grammar impedes the flow of good prose. And we surely cannot designate our unblocked mode as less intellectual merely because we cannot easily describe its delights or procedures.

I don’t deny

the differences in style and substance between athletic and conventional scholarly performance, but we surely err in regarding sports as a domain of brutish intuition (dignified, at best, with some politically correct euphemism like “bodily intelligence”) and literature as the rarefied realm of our highest mental acuity. The greatest athletes cannot succeed by bodily gifts alone. They must also perform with their heads, and they study, obsess, rage against their limitations, and practice and perfect with the same dedication and commitment that all good scholars apply to their Shakespeare.

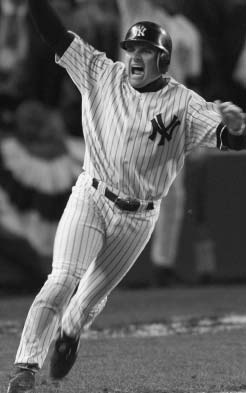

Yankee Chuck Knoblauch, in happier times, hits a home run in game three of the 1999 World Series against the Atlanta Braves. In the 2000 World Series against the Mets, Knoblauch would bat 1 for 10 as the designated hitter but would not play a single inning at second base.

Credit: Reuters New-Media Inc./Corbis

Mark McGwire, endlessly studying the videos of every pitch for every pitcher he will ever face, surely matches a careful scholar’s checking every last footnote for his monograph of a lifetime. McGwire’s mental skill may be harder to verbalize, but not because athletes are stupid or intrinsically less articulate than writers. Rather, this style of unconscious mentality gropes for verbal description in all domains of its operation. In my admittedly limited personal experience, I have found great performers of classical music even less able than ballplayers to articulate the bases for their success.

And so, to Chuck Knoblauch, a truly fine ballplayer, we can only say: This too will pass. I look forward to seeing you at the stadium on a cool day in late October. Top of the ninth, two outs, game seven of the World Series. Some National League victim hits a grounder to second, and you flip the ball deftly to first for the final out. Yanks win the Series, four games to three. And, following the conventions for scoring plays in baseball, this last out goes down in history with the code for a second baseman’s assist followed by a first baseman’s putout—4–3.

B

aseball did not win its central place in America’s heart and culture because the sport, in a silliness of common parlance, “imitates life” or stands as a symbol for larger truths and trends of human existence. Rather, baseball became America’s defining sport for the far more ordinary and concrete reasons of simple persistence and pervasiveness. One would have to inhabit a particularly tall ivory tower, or a particularly deep cave, to deny the status of sport as a central institution of human culture.

Baseball, as the codified form of a large variety of basically similar stick-and-ball games, has, like the poor, always been with us. Teams, leagues, and various lists of “official” rules had coalesced by the mid-nineteenth century, but Jane Austen refers to something called “base ball” in her 1797 novel

Northanger Abbey

, and various contests based on hitting a ball with a stick and scoring by running around bases came to America in the early days of European colonization, and then grew, diversified, and coalesced as the nation expanded and knit together.

Reprinted with permission from

Natural History

(March 2002). Copyright the American Museum of Natural History (2002).

One might assume, given the current popularity of football and basketball among Americans of all social classes, that these sports, rather than baseball, should carry (or at least share) the status of “national pastime.” But these games are neophytes in popular acclaim, as anyone of my generation will remember. They do boast a reasonably long following, but mainly as college sports. During my childhood, professional basketball and football were distinctly minor enterprises with short seasons and limited followings. Baseball, however, known to every sentient fan, and played with enthusiasm by farmers, street urchins, and swells (or whatever prosperous young men have been called at various times), has been keeping us together from our beginnings.

If I may offer just one person’s testimony, I am enmeshed in four generations of serious rooting. My immigrant grandfather acclimatized to America by watching Jack Chesbro win forty-one games for the New York Highlanders in 1904. My father regaled me with tales of Ruth and Gehrig, the ultimate secular gods of his world. I have been a passionate Yankee fan from the tears of joy at age eight for victory over the Brooklyn Dodgers in the 1949 World Series to bitter tears in November 2001 at a gruesomely painful ending in Phoenix—that is, from DiMaggio to Jeter. My son, a native of Boston, has switched to the Red Sox; he rises by the bashed dreams and plunges into the despairs of that particularly painful form of rooting. (I was especially touched when he interviewed me last year for a paper in his college sociology course on baseball as a mode of bonding between fathers and sons—though daughters will now be commonly included as well—especially in past generations when fathers, culturally restrained to far greater emotional distance, could use this opportunity for forging ties otherwise hard to establish.)

Baseball’s status as both a secular religion and an embodiment of important themes in American history imposes a common, yet paradoxical, problem for any exhibit dedicated to conveying the essence and vitality of the enterprise. How can a museum display two apparently different, even contradictory, aspects of a single subject at the same time, especially when both embody primary responsibilities of museums in general: the role of the reliquary (reverent displays of sacred objects, whose importance lies in their very being), and the role of the teacher (instructive display of informative objects, whose importance lies in their ability to inspire questions)? How can the awe of reverence mix with the skepticism of learning?

In my observations, only two museums have ever managed to solve this common dilemma in a consistent, even triumphant way: the Ellis Island Immigration Museum (where I can pay homage to my grandfather’s courage, as embodied in full walls devoted to respectful display of such humble but noble items as battered traveling bags and lockets of loved ones left behind, and also study the history of American immigration in any desired degree of detail) and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York (where I can immerse myself among the actual relics of our primary secular religion and also trace nearly any desired detail or generality about the history of baseball and its linkages to American life).

The wonderful selection from Cooperstown, on temporary display at the American Museum of Natural History starting this month, epitomizes this duality to near perfection and therefore gives us a lesson in how to hybridize these two greatest potential excellences of museums, despite their apparently irreconcilable disparity. In other (and more specific) words, we can learn a ton about baseball, while feeling both the spine shivers of contact with “holy” items and the touch of

genius loci

, the magic of real and special places.

To cash out my claims by examples on display, consider just five categories where the object as both relic and item for instruction forges potential synergy rather than frustrating contradiction:

1.

The embodiment of mythology

. As a supreme irony, the Cooperstown museum, as argued above, has covered itself in deserved glory, but still occupies an utterly inappropriate turf for the weirdest of perfectly reasonable circumstances—the very antithesis of

genius loci

. I say this not primarily for the practical reason that this tiny and isolated town in central New York State cannot find enough hotel rooms within fifty miles to house the crowds of people wishing to attend the annual induction ceremonies for the Hall of Fame, but simply because Cooperstown can stake no legitimate claim as a shrine for baseball. As argued above, baseball experienced no eureka of origin, but just grew, evolved, and eventually coagulated from a host of precursors. But humans need origin myths, so when baseball became enshrined as a national pastime, an official commission, established early in the twentieth century, was charged with the task of discovering baseball’s origins. For a set of complex reasons, the members of the commission allowed themselves to be persuaded that Abner Doubleday had effectively invented the game in Cooperstown in 1839. No even remotely plausible evidence links Doubleday to baseball. But Doubleday was certainly a sufficiently adequate American hero to embody an origin myth, for he had fired the first Union shots of the Civil War, as artillery officer at Fort Sumter, and he later served as one of the generals at Gettysburg.

In any case, myths require relics, so you may see on display the famous Doubleday ball—submitted as corroboration for the founding legend, perhaps discovered in Cooperstown, probably a bit younger than 1839, and surely possessing no plausible tie to Mr. Doubleday himself. I have also been told that enough nails from the true cross exist in European cathedral reliquaries to affix a hundred of Spartacus’s soldiers to their crosses on the Appian Way. Thank God that the human mind can embrace contradiction by acknowledging reality in the head yet respectfully allowing an imposter to stand for a symbol in the heart. (In a funny and recursive sense, moreover, once frauds achieve sufficient fame, they become legitimate objects of history in their own right!)

2.

Relics and icons

. If a reliquary really preserved a nail of the true cross, any Christian (I am not one) would bow in reverent awe, and any decent person (as I am) would stand respectfully before such an important item of history and symbol of human cruelty and hope. Well, this exhibit includes many true relics of a secular church that admittedly cannot claim similar importance but does mean one helluva lot to many quite sane and even reasonably perceptive people. Hey folks, I mean you’re really going to see the Babe’s bat from 1927 (the year he hit those sixty dingers for an “unbeatable” record), Roger Maris’s bat from 1961 when he broke the record, and Mark McGwire’s bat from when the record fell again in 1998. And because failure can be as sublime as hope (the raised Lazarus versus that nail of the true cross, although I know that Christian theology does not regard the Crucifixion as a dud), you will also see Michael Jordan’s bat from the year he tried baseball, discovered that he really couldn’t hit a curve ball despite being the world’s greatest athlete, batted about .225 in a year of minor league play, but stayed the course (and played the full season) with honor.

3.

Records of sacred events

. Churches and shrines not only boast general heroes, they also feature parables and stories of canonical import. Baseball revels in poignant, heroic, and defining stories by the dozen, and many items in this exhibition embody such crucial moments. But just as you need a scorecard to tell the players (an adage with baseball origins), so too do you need a tale to explain each of these items. So let me tell you just two stories of ultimate pain from two generations of Yankee worship in my family. (I suspect that cleansing drafts of pain match ecstatic quaffs of joy in any religion.) First, the 1926 World Series ring of Grover Cleveland Alexander. So what? Well (and you can see the scene yourself in an old film, with none other than Ronald Reagan playing the inebriated pitcher), here’s the setting: October 10, the deciding seventh game of the World Series, Cardinals against Yankees. The Yanks, just slightly behind in the score, load the bases in the seventh, and the Cardinals’ manager brings in his aged hero, the dipsomaniacal Alexander, who had pitched a full game (and won) the day before and then got stinking drunk, never expecting a call for the final contest. Tony Lazzeri at the plate, and my dad (age eleven) at the radio. Lazzeri hits one headed for the seats, a homer, and a Yankee victory, but the ball goes foul by a few feet. Alexander then strikes Lazzeri out and later wins the game. My father thought he would never again be happy but recovered two days later. Second, a ball used by Johnny Podres in the 1955 World Series. Well, I was walking home from school with my friend (and Dodger fan) Steve Cole, listening to the seventh and last game of the World Series. Podres won for the Dodgers, the only time (in their Brooklyn incarnation) that the Bums ever beat the Yanks in the World Series. I’m not sure that I’ve ever been truly happy since then. But wiser—and that’s more important, I suppose.

4.

Linkage to general culture

. Religion wouldn’t do much for us as a sanitized shrine, fully divorced from the spaces and realities of surrounding life. And as I noted to open this piece, baseball does not stand for America because the sport imitates life in some metaphorical way; rather, baseball illustrates nearly all aspects of America because the institution has been so central and important in our life and culture (and also because the basic rules of play have not changed for more than a century, so we can truly understand and feel the import of old happenings). Consider just two cardinal (if tragic) realities of our lives. First, war. The exhibition includes the most famous icon of all, the ultimate sign of baseball’s importance to the fabric of America: President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1942 letter to the baseball commissioner, urging that play continue during World War II so that symbols of normalcy might boost our morale. For other items, one needs a bit more explanation. I love the pairing of Moe Berg’s ID Card for the Office of Strategic Services with Bob Feller’s military goggles, both from World War II. Berg, baseball’s great raconteur and quite mediocre catcher, always claimed that he spoke at least half a dozen languages and had worked as a spy, tracking Werner Heisenberg and the German nuclear program during the war. His tales were widely disbelieved, but several recent studies have confirmed the basic story after all. Feller, the fastest pitcher of his generation, a rootin’ tootin’ midwestern conservative and a fighting man from day one, was a genuine military hero—never doubted for a moment, always honored, and God bless. Another item needs no explanation for its searing into recent memory: a baseball found in the rubble of the World Trade Center.

Second, the sad history of racism, where baseball has ever so much to answer for but finally responded well, albeit so belatedly. Again, humble items, easily bypassed, tell deep tales once one knows the context. Consider, for example, the baseball cards for Pumpsie Green and Larry Doby: Green, a utility infielder of no special merit as a player, wins his poignant role in this sad history as the first black player on the last team to integrate—shameful to say, the Boston Red Sox, from New England’s bastion of liberty. Doby, a truly great player for the Cleveland Indians, has never received his proper due because he came second, and our culture remembers only front-runners: Jackie Robinson, as everyone knows, integrated baseball with the Brooklyn Dodgers of the National League in 1947; Doby entered just after Robinson, as the first black player in the American League.

5.

Social spreadings and meanings

. Baseball has become so enmeshed within our general culture that I can only feel sorry for Europeans who, in watching American movies, have to be mystified by the young stud’s lament, “I didn’t even get to first base with her,” or who cannot appreciate the poignancy of a great moment in the history of tear-jerkery—when Gary Cooper, playing Lou Gehrig in

The Pride of the Yankees

, asks a physician who has just diagnosed the fatal illness that now officially bears his name, “Doc, is this strike three?”

Yes, you can use baseball to understand general culture. But the process can also work in the less-appreciated reverse direction by citing cultural norms to understand baseball’s peculiarities. To choose two examples, both auditory rather than visual this time: Everyone knows the ritual of singing “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” during the seventh-inning stretch, but where did this ditty—second in inanity and frequency only to “Happy Birthday” as an American universal—come from? The piece sounds like a pop song from the Gay Nineties or the early twentieth century—an entirely correct inference, by the way. But, as the Edison cylinder in the Museum’s exhibition shows, the words that we know and sing comprise only the chorus for a standard pop tune that has several verses as well. And the verses record the pleas of a young woman trying to convince her boyfriend to “take me out…”!