Triumph and Tragedy in Mudville (11 page)

Read Triumph and Tragedy in Mudville Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

May I object strenuously to rationales that make such an unfortunate use of legend, while legend itself veils so much of our important history?

A real baseball fan, told that Hoy should be in the Hall of Fame for one great day or for possibly instigating one item of cultural history, will rightly laugh and dismiss your argument. Athletes belong in the Hall for sustained excellence in play—for career performance, not momentary happenstance. Citing a legend only obscures the real point—or even suggests (to folks who do not consult the actual records) that the proper criterion may not truly apply in this case. But the real point could not be simpler: Dummy Hoy belongs in the Hall of Fame by sole virtue of his excellent, sustained play over a long career. His case seems undeniable to me. A dozen players from Hoy’s time have been elected with records no better than the exemplary statistics—particularly the great fielding and savvy baserunning, not to mention the more than adequate hitting—of Dummy Hoy.

I have tried not to stress Hoy’s deafness in citing his virtues throughout this article. But I suspect that Hoy’s deafness did deprive him of a necessary tool for the later renown that gets men into the Hall by sustained reputation. As mentioned earlier, Hoy never received much press coverage. Journalists refrained from interviewing him, even though he was the smartest and most articulate player in baseball. So Hoy was forgotten after he left the field—and his fierce pride prevented any effort at self-promotion. His inbuilt silence abetted the unjust silence of others.

I therefore end with one last example of Hoy’s wit—again from the letter written on his ninety-eighth birthday:

I am finding it harder and harder to write, to think, to decide on anything, or to act properly. In short, I am rapidly slowing up.

Let us therefore enshrine Dummy Hoy for whatever eternity means in baseball. Only then will we break the circle of silence that still surrounds this intelligent, savvy, wonderfully skilled, and exemplary man who also happened to be deaf, while giving his life to a sport never well played by ear.

I

n our sagas, mourning may include celebration when the hero dies, not young and unfulfilled on the battlefield but rich in years and replete with honor. And yet, the passing of Joe DiMaggio has evoked, in me, a primary feeling of sadness for something precious that cannot be restored—a loss not only of the man, but also of the splendid image he represented.

I first saw DiMaggio play near the end of his career in 1950, when I was eight and Joe was having his last great season, batting .301 with 32 homers and 122 RBIs. He became my hero, my model, and my mentor, all rolled up into one remarkable man. (I longed to be his replacement in center field, but a guy named Mickey Mantle came along and beat me out for the job.) DiMaggio remained my primary hero to the day of his death, and through all the vicissitudes of Ms. Monroe, Mr. Coffee, and Mrs. Robinson.

First published as “Harvard Prof. Pays Homage to Joe D.” for the Associated Press on the day of DiMaggio’s death, March 8, 1999. Reprinted with permission of the Associated Press.

Even with my untutored child’s eyes, I could sense something supremely special about DiMaggio’s play. I didn’t even know the words or their meanings, but I grasped, in some visceral way, his gracefulness, and I knew that an aura of majesty surrounded all his actions. He played every aspect of baseball with a fluid beauty in minimal motion, a spare elegance that made even his rare swinging strikeouts looks beautiful.

His stance, his home run trot, those long flyouts to the cavernous left-center space in Yankee Stadium, his apparently effortless loping run—no hot dog he—all were perfect. If the cliché of “poetry in motion” ever held real meaning, DiMaggio must have been the intended prototype.

One cannot extract the essense of DiMaggio’s special excellence from the heartless figures of his statistical accomplishments. He did not play long enough to amass leading numbers in any category—only thirteen full seasons from 1936 to 1951, with prime years lost to war, and a fierce pride that led him to retire the moment his skills began to erode.

DiMaggio also sacrificed records to the customs of his time. He hit a career high .381 in 1939, but would probably have finished well over .400 if manager Joe McCarthy hadn’t insisted that he play every day in a meaningless last few weeks, long after the Yanks had clinched the pennant. DiMaggio, who was batting .408 on September 8, had developed such serious sinus problems that he lost sight in one eye, could not visualize in three dimensions, and consequently slipped nearly thirty points in his average. In those different days, if you could walk, you played.

DiMaggio’s one transcendent numerical record—his fifty-six-game hitting streak in 1941—deserves the usual accolade of most remarkable sporting episode of the century, Mark McGwire notwithstanding.

Several years ago, I performed a fancy statistical analysis on the data of slumps and streaks, and found that only DiMaggio’s shouldn’t have happened. All other streaks fall within the expectations for great events that should occur once as a consequence of probabilities, just as an honest coin will come up heads ten times in a row once in a very rare while. But no one should ever have hit in fifty-six straight games. Second place stands at a distant forty-four, a figure reached by Pete Rose and Wee Willie Keeler.

Joe DiMaggio in 1949.

Credit: Bettmann/Corbis

DiMaggio’s greatest record therefore ranks as pure heart, not the rare expectation of luck. We must also remember that third baseman Ken Keltner robbed DiMaggio of two hits in the fifty-seventh game, and that he then went on to hit safely in sixteen straight games thereafter. DiMaggio also compiled a sixty-one-game hit streak when he played for the San Francisco Seals in the minor Pacific Coast League.

DiMaggio was a man of few words, and by no means a “nice guy” in his personal and private life. But he was possessed of consummate style and integrity on the field. One afternoon in 1950, I sat next to my father near the third baseline in Yankee Stadium. DiMaggio fouled a ball in our direction and my father caught it. We mailed the precious relic to the great man and, sure enough, he sent it back with his signature. That ball remains my proudest possession to this day.

Forty years later, during my successful treatment for a supposedly incurable cancer, I received a small square box in the mail from a friend and book publisher in San Francisco, and a golfing partner of DiMaggio. I opened the box and found another ball, signed to me by DiMaggio (at my friend’s instigation) and wishing me well in my recovery. What a thrill and privilege—to tie my beginning and middle life together through the good wishes of this great man.

Ted Williams is, quite appropriately, neither a modest nor succinct man. When asked recently to compare himself with his rival and contemporary DiMaggio, the greatest batter in history simply replied, “I was a better hitter; he was a better player.”

Paul Simon captured the essence of this great man in his famous lyric about the meaning and loss of true stature: “Where have you gone, Joe DiMaggio? A nation turns its lonely eyes to you.”

He was the glory of a time that we will not see again.

I

n

The Godfather, Part II

, gambler Hyman Roth laments that the real movers and shakers of society—kings and princes of the underworld—do not receive their proper public acclaim. He suggests that, above all, a statue should be erected to Arnold Rothstein for his brilliant and audacious job of fixing the 1919 World Series. In the lyrical novel

Shoeless Joe

, W. P. Kinsella tells the story of Ray, an Iowa farmer who, seated one spring evening on his porch, hears a voice stating, “If you build it, he will come.” Ray somehow knows that the unnamed man could only be Shoeless Joe Jackson, and that if Ray builds a ballpark in his cornfield, Jackson will come to play.

First published as the introduction to

Eight Men Out: The Black Sox and the 1919 World Series

, by Eliot Asinof, paperback edition (New York: Holt, 2000).

These tales, from such disparate men and sources, illustrate the continuing hold that the Black Sox scandal had upon the hearts and minds of baseball fans and, more widely, upon anyone fascinated with American history or human drama at its best. The “eight men out” of Eliot Asinof’s wonderful book—eight players of the Chicago White Sox, banned for life from baseball for their roles in dumping the 1919 World Series to the Cincinnati Reds—do not represent an isolated incident in an otherwise unblemished history of baseball. Links between players and gamblers, and the subsequent fixing of games, had become a scarcely concealed sore that threatened to wreck professional baseball in its youth during a difficult period of declining attendance and waning public confidence. Bill James pays homage to this book (in his

Historical Baseball Abstract

) by titling his discussion of game fixing during the teens and twenties “22 men out”—to show how many more beyond the Black Sox were accused. The others included such greats as Ty Cobb, Tris Speaker, and Smokey Joe Wood, but no plot was so sensational, no resolution so fierce as the Black Sox scandal. The “eight men out” of the Black Sox embody what can only be called baseball’s most important and gripping incident.

If we ask why this story so interests us more than a half century later, I would venture three basic sets of reasons:

First, so many aspects of the scandal are intimately bound—in interestingly ambiguous rather than cut-and-dry ways—with our most basic feelings about fairness and unfairness. We bleed for these men, banned forever from a game that provided both material and personal sustenance for their lives. They were not naive kids, tricked by some slick-talking mobsters, but seasoned veterans, embittered and disillusioned by a sport that had promised much, but had sucked them dry. We feel that, whatever they did, they were treated unfairly both before and after. Sox owner Charles Comiskey was not only the meanest skinflint in baseball, but a man who could cruelly flaunt his wealth, while treating those who brought it to him as peons. Later, when the Black Sox had been acquitted in court, the brass of baseball, behind their first commissioner, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, continued the ban nonetheless. On the other side, whatever the justice of their bitterness, the Black Sox did throw the Series, thereby betraying both their uninvolved (and mystified) teammates and a nation of fans. The oldest of all Black Sox legends, the story of the boy who tugged at Jackson’s sleeve as he left the courtroom and begged, “Say it ain’t so, Joe,” still has poignancy.

Second, history’s appeal for us lies largely in the fuel thus provided for the ever-fascinating game of “what if?” How would the subsequent history of baseball have differed if the 1919 World Series had been honest, or if other men and teams had been involved? We can focus on many themes, from the persistence of the reserve clause and the failure of players’ organizations (until recently) to the continuing power of the commissioner of baseball, an office set up in direct response to the Black Sox scandal. But consider only one personal item, perhaps the saddest result of all. Most of the Black Sox were fine players; pitcher Eddie Cicotte (29–7 with an ERA of 1.82 in 1919) might have made the Hall of Fame. But one man, Shoeless Joe Jackson, stands among the greatest players the game has ever known—and his involvement in the scandal wiped out an unparalleled career. His lifetime batting average of .356 ranks third (behind Cobb and Hornsby) in modern baseball, and the few who remember say that they did not see such a hitting machine again until Ted Williams arrived. Jackson turned thirty-three in 1920 (while batting .382), his last year of play. If age had begun to creep upon him, the records give no indication. Moreover, batting averages increased dramatically in 1920 and stayed high for twenty years, so Jackson’s unplayed 5–10 seasons might not have decreased this career record. Not that I can vote, and not that it matters, and not that this old issue will ever be settled—but Joseph Jefferson Jackson is the first man out whom I would put in the Hall of Fame. His sin is so old, the beauty of his play so enduring.

Third, putting emotion and speculation aside, the Black Sox scandal had an enormous and enduring impact on the nature of baseball, as much as any event since Cartwright or Doubleday or Ms. Rounders, or whomever you choose, first laid out the base paths.

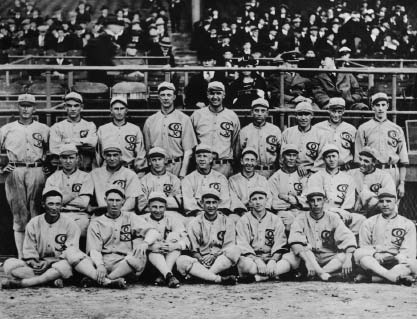

The 1919 Chicago White Sox.

Credit: Bettmann/Corbis

A few years ago, I began to study the statistics of batting averages through time. Ever since the professional game began in 1876, league averages for regular players have hovered at about .260. This equilibrium has been broken several times, but always quickly readjusted by judicious changes in rules. (For example, averages soared in 1894 when the pitcher’s mound was moved back to its current sixty feet, six inches, but they equilibrated within two years thereafter. Falling averages in the 1960s, culminating in Yaz’s league-leading .301 in 1968, led to a lower pitcher’s mound and a smaller strike zone—and averages quickly rose to their conventional .260 level.)

But one exception to this equilibrium stands out for impact and endurance. Starting in 1920, league averages rose into the .270s and .280s and remained high for twenty years (the

average

hitter in the National League exceeded .300 in 1930). The rise signaled the most profound change that baseball has ever undergone. Scrappy, one-run, slap-hit, grab-a-base-at-a-time play retreated and home run power became the name of the game.

Babe Ruth became the primary agent of this transformation. His twenty-nine homers in 1919 served as a harbinger of things to come, but his fifty-four in 1920—more by himself than almost any entire team had ever hit before in a season—sparked a revolution. Fans have long assumed that this mayhem was potentiated by the introduction of a “lively ball” in 1920, but Bill James has summarized the persuasive evidence against any substantial change in the design of baseballs (see his

Historical Baseball Abstract

). Rather, the banning of the spitball along with other trick pitches and, particularly, the introduction of firm and shiny new balls whenever old ones got scuffed or scratched were the primary agents—and based on equipment rather than people. (Before 1920, foul balls were thrown back by fans, and fielders would help their pitchers by scratching and darkening the ball whenever possible.)

If Ruth so destabilized the game, why didn’t the brass change the rules to reequilibrate play as they always had done before (and have since)? Why, in fact, did they even encourage this new trend with a changed attitude toward putting new balls into play and removing other advantages traditionally enjoyed by pitchers? The answer to this question lies squarely with the Black Sox and their aftermath.

The game had been in trouble for several years already. Attendance had declined, and rumors of fixing had caused injury before. The Black Sox scandal seemed destined to ruin baseball as a professional sport entirely. Thus, when Ruth’s style emerged and won the heart (and pocketbooks) of the public, the moguls of the game chose to view his style of play as salvation; and they permitted him to instigate the greatest and most long-lasting change in the history of baseball. Bill James puts the issue well in writing: “Under those unique circumstances [the Black Sox scandal and its sequelae], the owners did not do what they quite certainly would have done at almost any other time, which would have been to take some action to control this obscene burst of offensive productivity, and keep Ruth from making a mockery of the game. Instead they gave Ruth his rein and allowed him to pull the game wherever it wanted to go.”

Educator and historian Jacques Barzun wrote, in a statement often quoted, that “whoever wants to know the heart and mind of America had better learn baseball.” If baseball’s appeal, beyond the immediacy of the game itself, lies in its history and its mythology, then the Black Sox scandal represents a pivotal moment. For this incident sparked changes in all these areas: in the character of the game itself, in the history of baseball’s links to American society at large, and in mythology, by dispelling forever the cardinal legend of innocence. Innocence may be precious, but truth is better. Babe Ruth visited sick kids in hospitals, but he also did more than his share of drinking and whoring—and his play didn’t seem to suffer. Do we not all prefer

Ball Four

to the cardboard biographies of baseball heroes that were de rigueur before Bouton published his exposé? We must also understand the Black Sox if we ever hope to comprehend baseball. With sympathy, and with a tear.