Triumph and Tragedy in Mudville (6 page)

Read Triumph and Tragedy in Mudville Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

A

s performers in daily life, each of us can honor the best in our common human nature when we do justly, love mercy, and walk humbly. But as spectators of great accomplishments, we thrill to the transcendent moment of peak achievement in any honorable skill.

These rare and wondrous incidents—for we can only hope to witness a precious few in a full lifetime—unfold in two distinctly different modes. One is essentially democratic. Any good player—although odds favor the best, of course—can propagate a glorious moment of victory if circumstances conspire and skills permit: Carlton Fisk’s great home run in the 1975 World Series, or Ted Williams’s last hurrah, when he hit a dinger in his final at bat, to cite two local examples.

First published as “Greatness at Fenway” in the

Boston Globe

, July 16, 1999.

But the second mode is elite. We may, on the rarest of occasions, enjoy the privilege of watching a person who can do something so much better than anyone else on the planet that we have to wonder if he really belongs to our universal tribe of

Homo sapiens

. I can cite only two such experiences in my previous fifty-seven years of life, both musical: when, in the late 1960s, I heard Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau sing Schubert’s

Die Schöne Müllerin

, and even his triple pianissimos penetrated like pinpricks of utter beauty to my seat in the last row of the last balcony of Symphony Hall; and when, two years ago at the Metropolitan Opera, I saw the world’s greatest performers in each part boost their combined talents far above the sum of their individual strengths when they sang the first act of Wagner’s

Die Walküre

: Placido Domingo as Siegmund, Deborah Voigt as Sieglinde, and Matti Salminen as Hunding, with James Levine conducting the finest orchestra ever assembled in operatic history.

In Boston, we have just been treated to a fabulous doubleheader of similar import as the millennium closes on our shrine of Fenway Park—and I shall never forget the thrill and privilege of simply being there.

The All-Star Game itself is a spectacle, not a sporting contest (for no manager out to win a meaningful game would remove his best players early and use his final substitutes for a last comeback attempt). But spectacles serve the different function of showcasing excellence and affirming traditions worth preserving in a volatile and increasingly commercialized world, where material quantity becomes confused with ultimate worth, and where we seem unable to recognize and honor our older standards of human quality.

Mark McGwire’s baker’s dozen dingers in Monday night’s home run derby scarcely belong in a human league. His shortest shot over the Green Monster almost exceeded the longest single ball hit by any of the other nine contestants. (In the most awesome Fenway homer I had ever seen in thirty years of attendance, Jack Clark once hit the second row of lights in the left field tower that soars above the Green Monster; one of McGwire’s shots hit the very top of the same tower, while several others went higher and farther.)

Then, to begin the game itself on Tuesday night, our own Pedro Martinez struck out five of the six batters he faced, including, in order, Larry Walker, Sammy Sosa, and the same Mark McGwire.

American League starting pitcher Pedro Martinez pitches in the first inning of the All-Star Game at Fenway Park on July 13, 1999.

Credit: AP/Wide World Photos

Above it all (spiritually, as he linked my middle age to my childhood passion for baseball; materially, as he firmly threw out the first ball with the one side of his body that the ravages of stroke have spared; and literally, as he then watched the game from his left-field sky box), Ted Williams presided as the closest surrogate for God that such activities can muster.

Ted may not have been a “nice man” during his tumultuous playing days in Boston; and, although he didn’t starve, he never amassed a monetary fortune from baseball either. But Ted Williams directed all his maniacal dedication, and his gifts of body and mind, to pursuing—and achieving—his own dream of transcendence. He did not submit to the rules of corporate blandness or false modesty (now so essential for a lucrative life of commercial endorsements) in stating the driving goal of his choice in life.

As he has said so often, he “simply” wanted to become so good that when people saw him on the street they would turn their heads and say: There goes the greatest hitter who ever lived. And so he is. And so is Mark McGwire in the different art of power hitting, and Pedro Martinez in pitching finesse. And this—may we never forget, and never cease to practice—is the true significance and essence of enthusiasm, which literally means “the intake of God.”

I

n 1949, when Joe DiMaggio became my hero and the Yankees my passion, the Boston Red Sox led the Yanks by one game as the teams met in a final confrontation at the season’s very end. The Yanks won both and then took the World Series against their second-greatest rivals, the Brooklyn Dodgers.

A generation later, in 1978, my son (matching my own age in 1949) and I watched in delight as Bucky Dent’s flyball over the Green Monster (an out almost anywhere else, but a dinger in Fenway Park) beat the Red Sox in the only postseason episode—a one-game playoff to resolve a regular-season tie—of the greatest rivalry in the history of baseball.

First published in the

Wall Street Journal

, October 15, 1999.

The classicist Emily Vermeule, a colleague of mine at Harvard and an ardent Sox fan, wrote that destiny had deep-sixed the Sox because their drama with the Yanks had to unfold within the rigid norms of Greek tragedy. Roger Angell replied, in the greatest one-liner ever written about sports, that the pathways of history cannot be so foreordained. Mr. Angell offered the alternative view that—just as Yaz, representing the potential winning run, popped to third to end the game—God (who must support the Sox if the poor shall inherit the earth) became distracted, and chose this worst possible moment to shell a peanut.

And now these greatest rivals meet for the first time in a full postseason series (impossible previously, because two teams in the same division could not face each other in full postseason play before the recent introduction of the otherwise abominable “wild card”). Pedro Martinez vs. Roger Clemens on Saturday marks a promotion to reality of such fictional dreams as a poetry slam between Shakespeare and Marlowe, or a composition derby between Bach and Handel—as good as it gets in our imperfect world.

The first-round victories that have brought these teams together followed the scripted route for this quintessential drama. The Yankees, with the ruthless efficiency of baseball’s greatest and most frequent champions, dispatched Texas in a minimal three games, allowing the Rangers one paltry run in twenty-seven innings. (This year’s team features a wonderfully likable group of players—not always a hallmark of Yankee history, to say the least—but their personal amiability does not reduce the deadly force of the team’s juggernaut.)

I grew up in New York, now live here again, and have loved and followed the Yankees all my life. I would, moreover, never break a fealty of three generations extending from my immigrant grandfather who learned to love America by watching Jack Chesbro win a record forty-one games for the Yanks (then called the Highlanders) in 1904, to my father who worshiped Ruth and Gehrig, and who cried when Alexander struck out Lazzeri in the 1926 World Series. But after living in Boston for thirty years and holding season tickets in Fenway Park, the most captivating of all intimate bandboxes, how can I not love the Sox as well?

In maximal contrast to the Yankees’ smooth sail, the Sox lost the first two games in their best-of-five first round to the Indians in Cleveland, as their only two genuine stars, pitcher Pedro Martinez and shortstop Nomar Garciaparra, both went down with injuries. At Fenway for the third game, I sat with my seatmates of so many fruitless years, Jeff, Jay, Rob, Leo, and Jenny, all anticipating a wake but acknowledging the duty of our presence. The Sox won, 9–3. On Sunday, we enjoyed an even more improbable party as the Sox fractured the postseason record for runs, winning by a football score of 23–7. On Monday, back in Cleveland, Pedro Martinez, still hurting and unable to throw his best fastball, pitched six hitless innings, while Troy O’Leary’s two homers powered Boston to the most improbable comeback of recent memory.

Logic and reason dictate a swift Yankee victory in this second round, but such noble principles cannot buy a ticket to Fenway Park, where God may again shell peanuts at the crucial moment, or may not care enough even to attend, or may not give a damn about baseball, or may not even exist. This spectacle—the first postseason series ever played between baseball’s two oldest and greatest rivals—lies well beyond rationality. As Red Smith wrote, in the second greatest one-liner of sports literature, following Bobby Thomson’s series-ending home run in the 1951 playoff between the Brooklyn Dodgers and the victorious New York Giants: “The art of fiction is dead. Reality has strangled invention.”

Nothing can explain the meaning and excitement of all this to nonfans. No sensible person would even try. This is church—and nonbelievers cannot know the spirit. One can only recall Louis Armstrong’s famous statement about the nature of jazz: “Man, if you gotta ask, you’ll never know.”

I can only experience this Yankee vs. Red Sox series as eerie, for a rooterless benignity has descended upon me within an activity that demands partisan passion. I cannot abandon my lifelong fealty to the Yankees, but how can one live with Sox pain for thirty years and be unmoved or unattracted by the hope of redemption?

Just consider the possible scenarios. Yes, the first subway series since 1956 if the Yanks win and, however improbably, the Mets manage to vanquish the Braves. But suppose that the Sox win and the Mets also triumph. Then, in the last chance of the millennium, Boston gets an utterly unexpected opportunity to undo a century of humiliation from New York. This second round against the Yanks would redeem 1949 and 1978. A subsequent World Series victory over the Mets would then cancel the greatest pain of 1986 and restore the earth’s moral balance just before our great calendrical transition.

Boston could then exorcise the curse of the Bambino—the well-known hex put on the Sox when Boston owner Harry Frazee sold Babe Ruth to the Yanks in 1920 to raise enough cash to take a flutter on a Broadway show. (Boston last won the World Series in 1918.) The dreaded date of 1986 could be uttered again in Boston, and Bill Buckner, a fine player and gentleman who deserves a far better fate, can live the rest of his life in peace.

And Boston would stage its biggest and most memorable party since a group of hotheaded patriots dumped some tea into the harbor, an act that has reverberated for more than two hundred years—with the invention and spread of baseball, rather than cricket, as a primary ramification. These are indeed, as Thomas Paine said in an early reverberation, the times that try men’s souls.

A

highly inconvenient law of physics states that two objects cannot occupy the same space at the same time. Consequently, as New York rejoices in the first “subway series” since my high school days of 1956, we also lament that two of the three sacred places of past contests—Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field and the Giants’ Polo Grounds in upper Manhattan—now exist only as memories beneath housing projects, and not as material realities.

First published in the

New York Times

, October 19, 2000. Reprinted with permission of the

New York Times.

But I suggest a look on the bright side, spurred by a metaphor that Freud devised to begin his book with a quintessential New York title:

Civilization and Its Discontents

. Freud acknowledged the physical reality cited above, but he celebrated, in happy contrast, the mind’s power to overlay current impressions directly upon past memories. The mind, he argued, might be compared with a mythical Rome that could raise a modern civic building upon a medieval cathedral built over a classical temple, while preserving all three structures intact in the same spot: “Where the Coliseum now stands we could at the same time admire Nero’s vanished Golden House…. The same piece of ground would be supporting the church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva and the ancient temple over which it was built.” The physical fable fails, but we can, as Freud notes, make such an “impossible” superposition in our mental representations, for our memories survive, long after fate has imposed a sentence of death or the wrecking ball upon their sources: “Only in the mind,” Freud adds, “is such a preservation of all the earlier stages alongside of the final form possible.”

Thus, I can watch Roger Clemens striking out fifteen Mariners in a brilliant one-hitter and place his frame right on top of Don Larsen pitching his perfect game in 1956. And I can admire the grace of Bernie Williams in center field, while my teenage memories see Mantle’s intensity, and my first impressions of childhood recall DiMaggio’s elegance, in exactly the same spot. I can then place all three images upon the foundation of my father’s stories of DiMaggio as a rookie in the 1936 Series, and my grandfather Papa Joe’s tales of Babe Ruth in the first three New York series of 1921–1923.

The count of the last millennium stopped at unlucky thirteen in 1956. The reality of a subway series grew from more modest roots and routes. The first two New York series of 1921 and 1922 never left the Polo Grounds (for both the Yanks and Giants then played in the same park). Yankee Stadium opened in time for the 1923 three-peat of Yanks vs. Giants (and the first Yankee victory), but a short walk across the Harlem River sufficed, as the two ballparks stood in literal shouting distance, one from the other. Yankee victories over the Giants in 1936 and 1937 also required no more than a stroll. The first true subway series occurred a month after my birth in 1941, as distant Brooklyn finally prevailed. Six more subway contests between the Yanks and Dodgers followed (’47, ’49, ’52, ’53, ’55, and ’56), all won by Yanks, with a tragic exception in 1955. One strolling series between the Yanks and Giants intervened in 1951, as I struggled to restore my Yankee loyalty after rooting so hard for the Giants against the hated Dodgers—and being so gloriously rewarded by Bobby Thomson’s immortal homer in the last inning of the last playoff game.

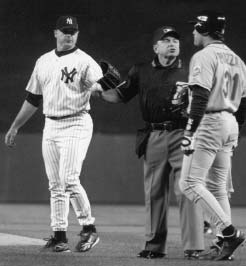

Home-plate umpire Charlie Reliford separates Yankees pitcher Roger Clemens from Mike Piazza in the second game of the 2000 subway series. Clemens had fielded a fragment of Piazza’s bat and thrown it in the Mets catcher’s direction as Piazza ran to first base on a foul ball.

Credit: AP/Wide World Photos

Geography then expanded even more dramatically from immobility in 1921, to a short stroll in 1923, to a subway ride in 1941, to a transcontinental flight, as several subsequent series pitted the Yanks against the transplanted Dodgers and Giants of California. But, to any real New Yorker, these contests simply don’t count. They left in 1958, broke our hearts, and then ceased to exist in that wondrous domain of Freudian superposition. The Mets, to me, are still an expansion team, but who’s complaining after a forty-four year drought, as subway series number fourteen initiates the new millennium?

What can I say? The subway series of my youth shaped my life and my dreams, and established the milestones of timing and memory for all later accomplishments. In the peace of midlife, just a few years shy of those senior discounts, I can even place the Freudian calm of experience upon the passions of unforgiving boyhood—and finally come to terms with the Dodgers’ victory, and the spoilage of Yankee perfection, in 1955. I met Roy Campanella at a university cocktail party several years ago. Incredibly, for this wonderful man exceeded all others present by an order of magnitude in interest and achievement, he sat alone, talking with no one. So I walked over, still in the awe of remembered youth, and knelt by his wheelchair for the most memorable half hour of conversation in all my life. He wore a World Series ring on each finger of his left hand, but one exceeded all the others in size and brilliance. So I said to him: “I know the year of that biggest ring. That must be for 1955, when you finally beat us.” And this great man simply replied with such heartfelt candor and pleasure: “Yes, I am so proud.” And, at that moment, and forever, a little, but persistent, wound of my youth healed, and all shone bright and good.