Triumph and Tragedy in Mudville (4 page)

Read Triumph and Tragedy in Mudville Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

A boy playing stickball catches a ball thrown to home plate, represented here by the manhole cover.

Credit: Ralph Morse/TIMEPIX

As any kid will affirm, the chief fascination of stoopball lies in the fact that no two stoops are exactly alike, and that, consequently, each stoop generates its own unique and idiosyncratic set of rules. A little story in conclusion: I once dislocated my arm during a stoopball game as I crashed into the side rail of the stoop when I ran in to catch a pop-up. So, one day, I’m sitting on the stoop, arm in a sling, when the local beat cop—as big, tough, and Irish as any stereotype of the profession could possibly suggest—sidles up to me and simply says, thus suffusing me with immense pride: “How’s the other kid?”

Boxball-baseball and using the sidewalk.

We played a wide variety of games by hitting a Spalding between two or three sidewalk chalk boxes. One could, for example, put a penny on the crack, to be awarded to the first contestant who hits it with a Spalding.

We called our local favorite “boxball-baseball” and played the game across three boxes, one belonging to each contestant, with the middle box neutral. The “pitcher” had to toss the Spalding into the neutral box, and the “batter” then had to slap the ball with the palm of his open hand into the pitcher’s box and hopefully far beyond on the subsequent bounce, with (just as in stickball and stoopball) the value of the hit determined by distance of the first bounce.

Baseball cards before the full hegemony of capitalism.

We had baseball cards in the late 1940s and throughout the 1950s. I even kept, while discarding all others, my favorite set of 1948 Bowman cards—black and white photos of players rather than Topps’s caricatures. My set is now worth several thousand dollars, but I’m not selling.

Nothing amuses (or puzzles) a fan of my generation more than the current treatment of baseball cards as commodities of distinctive monetary value. I confess that I laugh every time I see a kid these days acquire a new card and immediately transfer it to a plastic binder, lest, God forbid, an edge should become frayed, thus destroying the pristine value.

We collected cards, but never with a thought of money. We

used

them in a variety of games. You could stick them in the spokes of your bicycle wheel, where they made a pleasant whirring sound as you rode. But two utilities in real games predominated. First, we played flipping or matching. One contestant took a card and, from belt height, flipped it toward the ground, making sure that it turned several times on the way down. The other contestant then flipped his card—taking both if his matched the other in “heads” or “tails” of the final position, but losing both if his fell in the opposite orientation. Unlike the inability to hit pointers systematically in stoopball, a few neighborhood kids did learn—don’t ask me how, for I could never master the method—how to throw a heads or a tails almost every time.

Second, we scaled them against a wall. In this paper version of “pitch pennies,” each contestant scales a card, and the card closest to the wall wins them all. I once had sixteen identical cards of Ewell Blackwell—a fine pitcher, but not the greatest—and lost every one of them in a scaling game!

I could go on, but enough’s enough. We derived a great deal of enjoyment from these games. They also kept us out of trouble and away from girls. And what more could a boy have desired in preadolescence?

T

iny and insignificant reminders often provoke floods of memory. I have just read a little notice, tucked away on the sports pages: “Babe Pinelli, long-time major league umpire, died Monday at age 89 at a convalescent home near San Francisco.”

What could be more elusive than perfection? And what would you rather be—the agent or the judge? Babe Pinelli played the role of chief umpire in baseball’s unique episode of perfection—a perfect game in the World Series. It was also his last official game as arbiter—October 8, 1956. Twenty-seven Dodgers up; twenty-seven Bums down. The catalyst was a competent but otherwise undistinguished Yankee pitcher, Don Larsen.

First published as “The Strike That Was Low and Outside” in the

New York Times

, November 10, 1984. Reprinted with permission of the

New York Times

.

The dramatic end was all Pinelli’s, and controversial ever since. Dale Mitchell, pinch hitting for Sal Maglie, was the twenty-seventh batter. With a count of one ball and two strikes, Larsen delivered a pitch low and outside—close, but surely not, by any technical definition, a strike.

1

Mitchell let the pitch go by, but Pinelli didn’t hesitate. Up went the right arm for a called strike three. Out went Yogi Berra from behind the plate, nearly tackling Larsen in a frontal jump of joy.

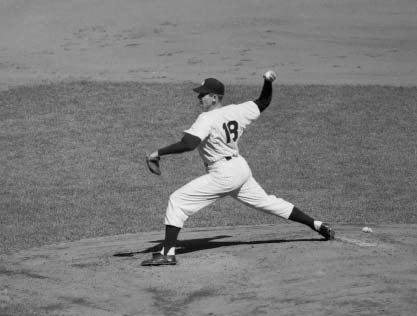

Don Larsen pitches the only perfect game in World Series history, leading the New York Yankees to victory over the Brooklyn Dodgers in game five on October 8, 1956. The Yankees ended up winning the Series in seven games.

Credit: Bettmann/Corbis

“Outside by a foot,” groused Mitchell later. He exaggerated, for it was outside by only a few inches, but he was right. Babe Pinelli, however, was even more right. A man may not take a close pitch with so much on the line. Context matters. Truth is a circumstance, not a spot.

I was a junior at Jamaica High School. On that day, every teacher let us listen, even Mrs. B., our crusty old solid geometry teacher (and, I guess, a secret baseball fan). We reached Mrs. G., our even crustier French teacher, in the bottom of the seventh, and I was appointed to plead. “You gotta let us listen,” I said. “It’s never happened before.” “Young man,” she replied, “this class is a French class.”

Luckily, I sat in the back just in front of Bob Hacker (remember alphabetical seating?), a rabid Dodger fan with earphone and portable radio. Halfway through the period, following Pinelli’s last strike, I felt a sepulchral tap and looked around. Hacker’s face was ashen. “He did it—that bastard did it.” I cheered loudly and threw my jacket high in the air. “Young man,” said Mrs. G. from the side board, “I’m sure the verb

écrire

can’t be that exciting.” It cost me ten points on my final grade, maybe admission to Harvard as well. I never experienced a moment of regret.

Truth is inflexible. Truth is inviolable. By long and recognized custom, by any concept of justice, Dale Mitchell had to swing at anything close. It was a strike—a strike low and outside. Babe Pinelli, umpiring his last game, ended with his finest, his most perceptive, his most truthful moment. Babe Pinelli, arbiter of history, walked into the locker room and cried.

L

ook, I’m a Yankee fan—have been since long before most of you were born. I have benefited from Boston’s suffering (most, after all, for Yankee gain) all my life. I reacted with boyish glee when, in 1949, Boston faced the Yanks one game up with two to go—and my guys won both for the pennant. And, although (honest to God) I didn’t want Yaz to make the last out by popping to third, I decided that Bucky Dent was the greatest living American one afternoon in early October 1978. The Red Sox, in other words, began as my mortal enemies.

That is, until 1967, the year of the Impossible Dream, and my rookie season in the Harvard professoriat. I loved that pennant race and cheered Boston on (why not, the Yanks were out of it, and one of my New York heroes, Elston Howard, was catching for the Sox). For the first time in my life, I suffered with you through the seventh Series game—though the final result was inevitable (I mean nobody but nobody could beat Bob Gibson, not even Lonborg, especially on two days’ rest).

First published in the

Harvard Crimson

, November 5, 1986.

My affection for Boston crept slowly apace until it blossomed in 1975, and I began to understand Boston pain. I watched the sixth game of the Series from a hotel room in Salt Lake City (no beer, not even before the seventh inning), and exulted in Carlton Fisk’s homer with a glee unmatched since Bobby Thomson’s for the Giants in 1951. I also watched, from the same room, the next day as the Sox, in the finale, took a 3–0 lead into the sixth, and then blew it.

This cocky Yankee fan, accustomed to victory as a rite of fall, began to understand the uniqueness—also depth—of Boston’s special pain. Not like Cubs pain (never to get there at all), or Phillies pain (lousy teams, but they did take it all)—but the deepest possible anguish of running a long and hard course, again and again, to the very end, and then self-destructing one inch from the finish line.

Well folks, guess

what? Call it shallow, fickle, or anything else you want. But this year I was with you all the way. The Yanks never had a real shot (and Steinbrenner does wear on you after a bit). Maybe you thought I would switch caps for the Series and start chanting “Let’s Go, Mets.” Not on your life. I’m a loyal New Yorker, to be sure, but the Mets are nothing to me. They didn’t exist when I was a kid, and loyalties are shaped by those early years of splendor in the grass and glory in the flower.

I rooted for the Sox all the way, as hard and as diligently as I ever rooted in all my life (and spurred by my son Ethan, a Sox zealot too young to remember any previous postseason play).

What can possibly be said? It’s a week later, and I’m still numb. To hell with the French Revolution; to hell with Dickens. This, not that, was the very best, and then the absolute worst, of times.

When, a millimeter from final defeat (with the champagne already uncorked in the Angels’ dressing room), Dave Henderson hit that fifth-game homer, I reacted as I never had before. I didn’t cheer or jump; I wept—not a few tears stifled by the customs of manhood, but copiously. Then, alone again in a hotel room (this time in D.C.), I had to watch when Henderson, reaching for immortality, apparently won the Series with another homer in the tenth inning of game six, and, with two outs and nobody on, the Sox came—not once but four times—within a micron of taking it all, only to blow it once again.

The Mets’ scoreboard had already flashed “Congratulations Red Sox.” NBC had already named Marty Barrett player of the game, and Bruce Hurst the Series MVP. But the Sox knew better. They had peeled the aluminum off the champagne bottles, but they hadn’t popped the corks. You all know what the great Yogi Berra says about when it’s over—and when it ain’t.

Yes, I do understand finally. I came to it late, but I do understand now. This was worse, more bitter than ever. A total self-immolation, by guys we love and admire—by Calvin Schiraldi, who got us there; Rich Gedman, who performed with such quiet efficiency; Bill Buckner, who, though hobbled, had fielded flawlessly. I even grieved for Bob Stanley (nine times out of ten, Gedman stops that ball, even though it must technically be ruled a wild pitch; and Stanley did what he was brought in to do—he got Mookie Wilson to hit an easily playable ground ball). Yes, this was much worse—worse than selling that great lefty pitcher named Ruth, worse than Pesky holding the ball in 1946, worse than facing the Gibson machine in 1967, worse than Joe Morgan in 1975, worse even than Bucky Dent and Yaz’s pop to third in 1978.

What does it all mean? (We academics do have to ask that question after all.) I held and abandoned my hypotheses in this vein during postseason play. After Henderson’s resurrection in playoff game five, I actually dared to suggest that God was a Red Sox fan. After the most providential rain delay in recent sports history, between games six and seven of the Series, I decided that God cannot influence human actions, but still controls the weather. After the last game, I realized that He must hate the DH rule so much that He only favors the Sox within the American League. (I must, of course, now also entertain the possibility that either he doesn’t exist at all or doesn’t give a damn about baseball.) We are left alone with our pain.

The finale was too typical—an early Sox lead, eroded near the end; a late Sox surge, almost but not quite enough. Ethan cried when it was all over—and this was only his first time. I tried to console him, but ended up joining him. It’s a puzzle, isn’t it? I don’t know why grown men care so deeply about something that neither kills, nor starves, nor maims, nor even scratches in our world of woe. I don’t know why we care so much, but I’m mighty glad that we do.

T

ime flows in many ways, but two modes stand out for their prominence in nature and their symbolic role in making our lives intelligible.

Time includes

arrows

of direction that tell stories in distinct stages, causally linked—birth to death, rags to riches.

Time also flows in

cycles

of repetition that locate a necessary stability amid the confusion of life—days, years, generations.

Cycles of repetition, based in nature, once surrounded us and shaped our daily lives. We sowed in the spring, reaped in the fall, froze in the winter, and frequented the ol’ swimmin’ hole in the summer.

Urban life has vitiated these rhythms. We become insensible to seasons in a world of air-conditioning and nectarines available throughout the year at Korean all-night fruit stores.

First published in the

New York Times

, April 4, 1988. Reprinted with permission of the

New York Times.

We must therefore create cycles from the flow of culture—for our need has not abated. Thus, we celebrate holidays and other largely artificial rituals, set at appointed times. The seasons may be utterly lost in Southern California, but San Diegans still eat turkey in November, spend money in December, and watch fireworks in July.

Spring marks the true beginning of the year. Spring signifies renewal, rebirth. Spring (up here in New England, where seasonality still pokes through the asphalt jungle) is the yearly sequence of crocus to forsythia to tulip to rose. The Romans understood and began their year at this right time—so that September, October, November, and December (as their etymology still proclaims) were once the seventh, eighth, ninth, and tenth months of a year that started in March.

But spring, to all thinking, feeling, caring, red-blooded Americans, can only mean one thing—if you will accept my premise that culture must now substitute for nature in symbols of cyclic repetition.

Spring marks the return of baseball—opening day, the true inception of another year. Forget the inebriation of a cold January morning. Time, as Tom Boswell so aptly remarked, begins on opening day.

Baseball fulfills both our needs for arrows (to forge time into stories) and cycles (to grant stability, predictability and place).

Opening day marks our annual renewal after a winter of discontent. But opening day also records the arrow of time in two distinct ways.

It evokes the bittersweet passage of our own lives—as I take my son to the game, and remember when I held my father’s hand and wondered if DiMag would hit .350 that year.

And opening day promises another fine season of drama—an arrow that will run through October, telling its stories of triumph and tragedy as the world turns and yet another summer cycles past.