To Reach the Clouds (17 page)

Read To Reach the Clouds Online

Authors: Philippe Petit

My eyes have now adjusted to the absence of light. Despite the frantic work, I am glancing at the north tower every three seconds. Gradually, a minuscule antenna rises from its smooth, dark silhoutte, dead center. It's Jean-Louis's arm, now erect and motionless: he is ready to shoot and is waiting for my signal.

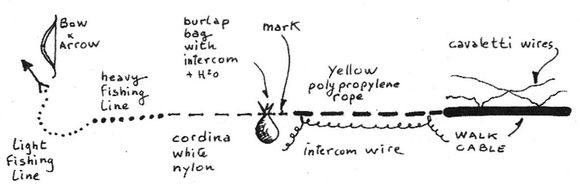

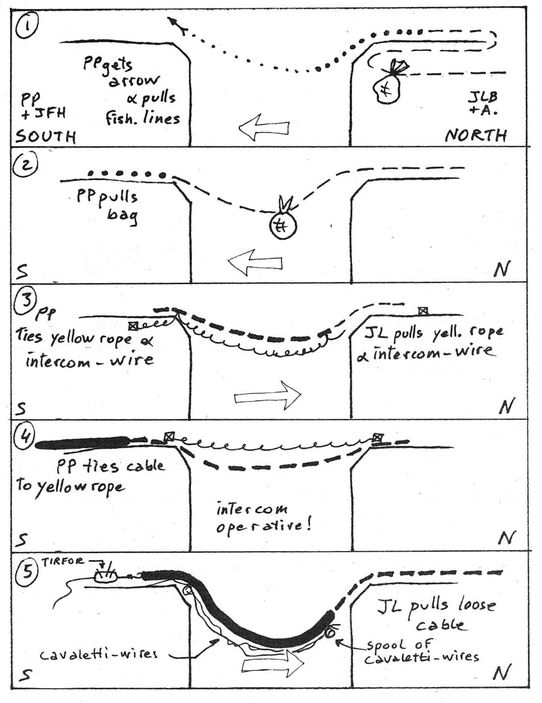

I am supposed to raise my arm for ten seconds in response, and then Jean-François and I are to lie flat for protection under the foot-high window-washer tracks. Jean-Louis will count to ten, aim the bow at the New Jersey shore to allow for the strong westerly wind, and shoot the arrow carrying the fishing line. As rehearsed, the arrow will land near the center of my rooftop.

I am not ready.

And we don't have a signal for “I am not ready.”

Having unrolled the walk-cable, I am still fighting with the cavaletti linesâa wrong move uncoiling them would mean an extra hour of work, time I don't have. And I am still running back frequently to the narrow staircase opening where Jean-François's head is still plunged, on the lookout.

The nonstop unrolling of so many feet of cable is taking a toll on my back, so I whisper to Jean-François to take over, and we exchange tasks. But kneeling on the cold concrete with my head upside down is unbearable; I prefer breaking my back. With a millisecond of admirationâWow, how does he do it?âI order my friend back to his post.

Finally, the cavalettis are laid out.

Valiant Jean-Louis! For what must be twenty minutes, he keeps his arm raised for me to see. Before I signal in answer, I look at Jean-François's kneeling silhouette, which is more or less in the bull's-eye. Shall I pull him away from his watch, or risk having him shot? I snigger at the image of early workers discovering a still-warm French corpse, arrow through the heart, amid abandoned ropes and cablesâhow would the headlines read? But I can't finish the rigging alone!

In six silent giant steps, I reach Jean-François and swiftly tiptoe him back to the relative safety of the steel tracks.

I raise my arm.

We count to ten, then dive under the tracks, trying to leave no limbs exposed. We hide our heads in our hands, but I pry open my friend's fingers so that he can keep watch on the staircase opening, and I uncover one of my eyes to keep Jean-Louis's arm in view.

Jean-Louis brings his arm down and raises it again, in acknowledgment of my signal. Then the arm lowers slowly and fades into the penumbra of the rooftop. Jean-Louis must be starting his ten-count before shooting. Jean-François counts with me in a whispered echoâ“One-

one, two-two, three-three,

four

four”

âand, as my panicked voice falls silent, he finishes:

“Five-six-seven-eight-nine-ten!”

one, two-two, three-three,

four

four”

âand, as my panicked voice falls silent, he finishes:

“Five-six-seven-eight-nine-ten!”

Like escaping prisoners, we hold our breath and lie perfectly still: we are listening to the night, 1,350 feet above the ground.

Nothing!

Shouldn't the arrow be airborne already? Did the fishing line break?

Was that a faint metallic

cling

I just heard?

cling

I just heard?

I send Jean-Francois back to his watch at the staircase; I go hunting for the arrow, but my legs are cottonlike; I taste bile. I am worn out, about to faint, in raging despair. Jean-Louis has missed. The coup has failed.

Â

A physical defiance has me crawling in the dark on all fours, in all directions. Nothing! I sweep the rough concrete surface, scraping my hands. Still nothing!

Back on my feet, crouched over to hide my silhouette, I run back and forth along the north edge of the roof. Nothing, nothing! I pass again, this time scraping against the beams of the perimeter, one arm raised above my head in case the line is floating in the breeze, one arm stretched out toward the lower ledge in case the thread is caught there. Nothing. No thread. No arrow.

I am determined to find this invisible thread in the windy darknessâeven to invent it! Without thinking, I tear off my clothes. My naked body will locate what my hands could not. Arms out, like a blind beggar in a Bruegel painting, forgetting to hide, I scout the obscurity, I stumble over the equipment, I fall. I collect cuts and scratches, but no fishing line.

Incensed, I attempt to calm my thoughts by leaning against the northwest corner and staring dementedly at the murky Hudson River, where the arrow may have drownedâwhen on my hip I feel the incredibly sweet caress of a fishing line undulating in the chilly wind.

I walk my fingers along the line until they reach the arrow, which isâunbelievablyâdelicately balanced on a steel channel girt over the abyss. Another half inch to the west and it would have missed the tower. I close my hand around the arrow just as a sudden draft threatens to dislodge it.

Now I am in heavenâand freezing from head to toe.

I dash to share the news with Jean-François, whoâhead still inverted in the stairwellâcan't see I'm naked. I pull the fishing line across and get dressed. Then comes the second fishing line, heavier and strongerâI can feel Jean-Louis's hands paying it out.

Got it!

I keep pulling. It's so smooth, so easy, I laugh out loud.

Now I have the cordina, the white nylon parachute cord. I tension it a bit, fasten it to the flat bar with a clove-hitch-in-the-bight, and add a black dot with a marker, as does Jean-Louis, I'm sure. Later, we'll know who won a contest we started in Vary, to guess the distance between the two anchor points.

I wave at Jean-Louis in the obscurity, even though he probably can't see me.

I allow myself a moment of rest. Then I climb down onto the lower ledge, carefully lean over the emptiness, and pee onto the plaza, scribing the word

happiness.

happiness.

Rigging continues effortlessly. I bring in more and more of the loose cordina until the north tower resists. I cannot see, but I know they are now attaching the burlap bag containing my intercom unit, the water, and a few tools. I wait. I get a signal. I resume pulling. I feel the weight of the precious burlap bag dangling in the air. I'm so impatient to talk to Jean-Louis, I want to be able to pull it to me in one unbroken stroke. The thin line, now loaded, hurts my fingers. The cordina stops! What's happening? I pull harder, but it's stuck.

Oh, Jean-Louis must have hit a little knot, courtesy of Murphy's Law. I wait for him to untie it.

Â

Pulling again brings me only a few inches of cord, and those are given by the elasticity of the nylon fibers, not by Jean-Louis's hands. I wonder if the burlap bag is stuck on the north tower's crown, invisible to Jean-Louis in the dark. I pull and I pull.

Nothing!

Nothing!

I cast a temporary clove-hitch-in-the-bight around the flat bar and run to steal Jean-Francois from his watch. Dizzy from holding his head upside down for so long, his knees crushed, the poor lad must hold my arm to limp to the cordina. We pull and we pull to our strength's limit. To no avail.

I send Jean-François back to his postâhe goes crawlingâand I keep looking into the void, baffled: how can a line be stuck between two roofs?

Â

Suddenly I make out the bag: it's swinging in the dark, less than sixty feet from me!

This time I have something tangible to fight for. I set my eyes on the bag and go for it with all my might. The bag dances even more, but does not get closer. I pull until my arms give up.

I remember reading somewhere that the legs are stronger than the arms, so I sit down, legs bent, feet against the edge's flat bar, holding the cordina with both hands. I try to extend my legs. I push and I push, until my calves shake. The bag does not budge. Once more I try, this time letting frustration and rage replace brute strength. The bag comes my way an inch, then refuses to move any more.

Â

This is an enigma.

I tie the cordina, stand up calmly, and try to reason. A master of rigging, I must come up with an answer. I cannot. It hurts. So I do what I've done all my life. I rely on intuition. My silly childish intuition whispers to me the most preposterous advice: “If it does not work now, wait. Maybe it'll work later.”

I wait for ten minutes, hands on hips, staring at the bag dangling in midair. Then I go for the cordina, but at the last moment change my mind: if time is solving the problem, let's give time more time! Proudly I stand, arms crossed, as I watch the bag for another ten minutes.

“That should do it,” whispers the silly child in me.

Â

I untie the cordina and pull. The bag glides towards me. I keep pulling with ease. The bag lands softly at my feet. Oh! There's a little note from Jean-Louis taped to the tie: “Welcome.”

I open the bag joyfully and connect my part of the intercom to the 200-foot electric cord already laid out on my roof. To pass that cord to the north tower, I will pair it with the thick yellow polypropylene rope. I quickly tie one end of the yellow rope to my end of the cordina, using a double-sheet-bend. A few feet from the knot, I make fast one end of the cord to the yellow rope with a double-rolling-hitch with six round-turns. I signal the north tower to pull the cordina. With one hand, I ease the yellow rope into the darkness while I gently pay out the cord with the other, until it hangs under the full length of the rope. The yellow rope is light and smooth, easy on the hand, and all goes very well.

A few minutes later, the north tower is connected!

Jean-Louis awaits my greetings.

Â

“What the hell happened?” I imagine my words walking across the chasm along the thin electric wire, all the way to my good friend's ears.

“Hey, Philippe, didn't you think that if we didn't give you the cordina, it could be we were having a problem here? Couldn't you just wait?”

“What problem?”

“Well, the bag was already two thirds across, and dancing a lot, when I saw a guard two floors beneath you, looking out the window. Because of the slack in the cord, the bag was swinging a bit above his head, but right in front of him. It was a miracle: he was looking at my tower, he was looking down at the plaza, but he never looked up. He would have seen the bag, even in the dark! So I stopped. But you kept pulling. And the more you pulled, the more the bag was dancing!

“I tried to stop your pulling, but god, you were pulling like mad. I guess when you're mad, you're pretty strong. I had to ask Albert to come help me! And then we waited a good twenty minutes. And then the guard left. So we released the cordina.”

The next thing out of the burlap bag is the bottle of water. I have an excuse for not sharing with Jean-Francois: he is too far away, absorbed in his upside-down vigil. Just as I take a mouthful of the quenching liquid, two hands grab my neck from behind. I spurt out all of it, coughing with fright.

“You scared me,” I reproach Jean-François, who has come to announce that his guard is gone. “Let's run for it,” I say, closing the bottle in a hurry; another excuse for not offering a drink to my friend.

Â

We fly down the stairs; we bring all the equipment to the roof in three trips. “The shoes!” I go to retrieve them while Jean-François starts unwrapping the balancing pole. We painstakingly assemble it and hide it. Why? I couldn't say.

I have the urge to give Jean-François a big hug, but that would be a loss of time. I run from one task to another, trying to anticipate what the next move will be, which I'm rarely able to do. When the silent night is pierced by the intercom's repeated buzzâtoo loud even at the lowest volumeâI drop whatever I am doing and dash to answer, banging into the equipment and cutting myself on the sharp edges of beams.

This bruising routine will be repeated throughout the night.

Â

Laboratory rats in their cages, when hit by an electric jolt, take it a few times, then learn to avoid it. Not I.

Other books

Alaska Heart by Christine DePetrillo

Fuzzy Navel by J. A. Konrath

The Sorcerer of the Wildeeps by Kai Ashante Wilson

The Last Second by Robin Burcell

The Assembler of Parts: A Novel by Wientzen, Raoul

Blood Slave: A Realm Walker Novel by Kathleen Collins

Dunston Falls by Al Lamanda

Divided Enchantment (Unbreakable Force Book 4) by Kara Jaynes

Paige's Warriors (Bondmates Book 3) by Ann Mayburn

Last Ranger by Craig Sargent