To Reach the Clouds (13 page)

Read To Reach the Clouds Online

Authors: Philippe Petit

A woman in the front row attempts to strike up a conversation with me as I am passing my hat after my performance outside the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She's a casting director, working on a project with Dustin Hoffman.

I mime “not interested” and pass. She trots after the hat to drop in her business card. I pick up the card, smell it, bury it in my pocket, and, lifting one eyebrow, present the hat to her. She throws in a dollar.

Much later I remember the card. I call.

Â

On the top floor of a Madison Avenue skyscraper, I am invited into a comfortable wood-paneled office and left alone.

I press my nose to the window, admiring the view from fifty stories up. Hoffman comes in and holds out his hand to me, but lost in the void, I make him wait before shaking his. “Hey, it's pretty nice up here!” I say.

The actor is relaxed and smiling. He offers me some wine, then explains that he is directing a theatrical production having to do with circus arts, and because his collaborators admired my street-performing, he wanted to meet me, and he proposes to hire me for â¦

Almost from the beginning I lose interest, and the corky young wine annoys my palate. “I'm not only a street-juggler, I'm also a high wire walker, look!” I say, flipping the pages of the huge photo album I brought with me. “See? Here in Paris, here in Sydney, all without permission!”

I explain I cannot consider his offer because I'm busy working on a surprise high wire walk.

He asks where, when.

“Oh, that I can't tell. It's a secret! I'm going to put a wire without permission between two buildings, somewhere in New York City!”

“Well, I can tell you a great place to put a wire,” says the actor, beaming.

“Where?”

“The World Trade Center!”

“You mean those two big towers all the way downtown? Brilliant idea!” I comment, discreetly pouring my wine into a crystal vase full of roses when the actor is not looking.

On my way to the door, I ask if he would like to come to the show.

“Oh, absolutely!” he replies, frowning in puzzlement at the purple water in the vase.

I tell him that once the cable is up and I'm ready to walk, I'll have accomplices calling the press and then a list of friends. I offer to add him to the list.

“Yes, please, that would be nice.”

“But it's possible they'll call you at six a.m.”

“It doesn't matter. I want to be on the list! I want to be on the list!” the actor says with amused disbelief, giving me his phone number.

Usually, when I decide to gather everyone at West 22nd Street to rehearse the coup, the Americans arrive late or cancel at the last moment. When I do manage to assemble everyone, invariably Donald interrupts by playing the piano. He insists that I add padding to the equipment going to the roof, so that he and his friend won't hurt their shoulders. And Chester has been growing increasingly distant.

Today, he announces he is no longer able to help me in the towers.

Panic-stricken, I call Jean-Louis, who has someone else in mind.

But the Americans have a friend to replace Chester: someone brisk and agile who has worked on a boat, someone who knows all kinds of knots.

They've told him everything!

Â

My first meeting with Albertâa nimble young man with short black curls and moustache, wearing glassesâleaves me with an intuition of distrust. I like his intelligence and seriousness, I sense he can follow any adventure, get out of any trap, and he shows me a few knots I'm not familiar with; but his enthusiasm is guarded and he chooses his words as he speaks.

Albert is also a photographer, and he offers to shoot the walk as well as help with the rigging. I explain that Jean-Louis is to be the exclusive photographer of the coup, and Annie insists that Albert must not take any pictures, even as souvenirs, “Or else it's better you're not part of the coup at all!” I'm flabbergasted at Annie's ultimatumâa potential disaster, so close to the walk. But Albert answers in a detached tone, “Fine, fine ⦠I don't give a shit about photographs.”

Jean-Louis calls from Paris. “How about that young guy who helped us at Notre-Dame?”

I don't have the faintest idea who he's talking about.

“Oh come on, Philippe, don't be disgusting. You know, Jean-Françoisâhe saved your life!” Jean-Louis reminds me that Jean-François had agreed to help at Notre-Dame only if he were sure to be freed in the morning in time to play an important tennis match. I had, of course, promised him the moon. An exhausted and dirty Jean-François had showed up on the court very lateâand won.

“Yeah, it vaguely rings a bell,” I say unenthusiastically, “but it isn't necessary to get anyone else since I have enlisted this genius new guy who has already accomplished his first mission:

he spent the night in the south eighty-second-floor hiding place and brought back a complete activity report, and ⦔

he spent the night in the south eighty-second-floor hiding place and brought back a complete activity report, and ⦔

Jean-Louis hangs up on me and places another call.

In an isolated hamlet in the south of France, the phone rings thirty times in a tiny house surrounded by fig trees. A young feminine voice puts the caller on hold.

Â

The girl runs after her boyfriend, who has gone up a brook looking for pebbles. Jean-François's childish silhouette, perfectly proportioned, bare-chested and barefoot, is kneeling on a rock. His baby face, framed by thick, disheveled golden locks, wears a beatific smile. Clutching a handful of shiny pebbles, he is admiring a butterfly delicately perched on his knuckles.

“Jean-Francois, quick, someone is calling from Paris!”

Â

“

Allo?

Ah, my dear Jean-Louis! How is life treating you? And to what do I owe the pleasure of ⦠New York? How? ⦠Oh, you'll arrange it ⦠Yes, in Paris. Day after tomorrow. Bye!âOh, Jean-Louis? ⦠Would you be kind enough to inform me of what is going on? ⦠Without permission, I see ⦠And you're looking for an uncomplaining sherpa who is ready to spend some time in jail ⦔

Allo?

Ah, my dear Jean-Louis! How is life treating you? And to what do I owe the pleasure of ⦠New York? How? ⦠Oh, you'll arrange it ⦠Yes, in Paris. Day after tomorrow. Bye!âOh, Jean-Louis? ⦠Would you be kind enough to inform me of what is going on? ⦠Without permission, I see ⦠And you're looking for an uncomplaining sherpa who is ready to spend some time in jail ⦔

Jean-François hangs up, smiling.

Â

“What was so urgent?” worries his girlfriend.

“Oh, nothing,” he answers calmly. “I have to leave for a few days.”

“Where are you going?”

“Mmm, to New York!”

Security is improving at WTC.

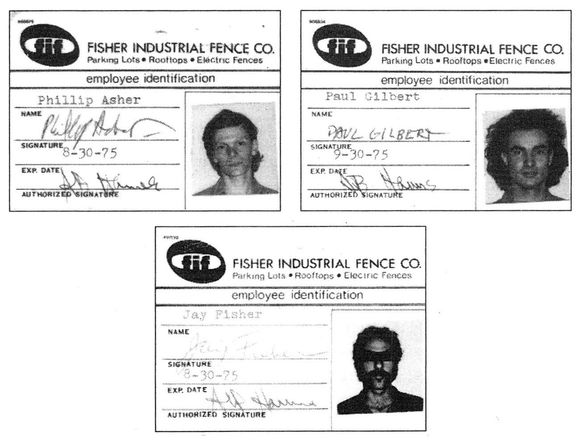

Barry calls to tell me that from now on every employee must carry an identification card: he received his today. “Would you by any chance be interested in”âhe clears his throat and lowers his voiceâ“seeing it?”

Â

Only minutes laterâI was at One Hudson Street, building a table for JimâI appear in front of a dumbfounded Barry. I grab the I.D. from his hands and rush home to study the document.

The thing is too professionally done. I don't stand a chance. Plus, I left my counterfeiting kit in Paris. Nonetheless, I give it a try. By midnight, all my replicas end up in the wastebasket, from which I retrieve them a moment later to throw them in the fire.

But what about, at the time of the coup, providing the group with an identification card of its own?

Back to the drawing board. I open the Yellow Pages at random and point at a name: Fisher. I design a logo for the nonexistent Fisher Company, which specializes in electrified fences and roofing.

By 3 a.m., the result is awful. And I don't have the time for that!

Â

In the morning, Jim saves the day. He has a friendâa graphic designer.

I rush my seven lousy I.D.s to the expert, satisfy him with a haphazard explanation and quite excitedly offer my help. He is a craftsman, accustomed to working alone, and he does not need my agitation. “Take a walk instead,” he advises.

In the evening, I pick up the improved documents: they're perfect.

Very nicely, the man offers to fill in the names and expiration dates, adding that his wife is an excellent typist.

Instantly, I come up with fake names.

By now, the woman has put the first card in the typewriter.

“Stop!” I shout. I ask her to try first on a piece of paper. With a lovely smile, she assures me that it is not a problem for her to type

a few words accurately. After all, she's a professional typist, she says, placing her fingers back on the keyboard.

a few words accurately. After all, she's a professional typist, she says, placing her fingers back on the keyboard.

I jump up and pull the card from the machine, fumbling apologies. These documents are so important to me that I'm not willing to take any risk, I explain. And since there is no time to make a new batch, I prefer to find a typewriter and do it myself.

Yielding with grace to my paranoia, the woman complies: on a separate sheet, she types the seven names and dates in less than thirty seconds, rips out the paper, and hands it to me with a smile of superiority.

I point out the three typos.

Â

The champion speed-typistâon the verge of tears, and in the most deadly silenceâtypes each entry with one trembling finger, one letter at a time, on the precious cards.

I heap a profusion of thanks and apologies on the carpet and flee with my treasures.

Five days before the arrival of Jean-Louis and Jean-François in Bostonâthe only available flight on such short noticeâI organize a dress rehearsal.

Organize? Not really.

To Albert and Donald, I transmit my wishes: we need to spend a few hours out of New York, in complete privacy, on a secluded flat piece of solid land bordered by a few trees, so that I can try out the equipment and show them the rigging sequence. They say they'll organize it, no problem.

No problem? Not really.

Â

Albert is great. He gets hold of a car. He finds a friend who has property in upstate New York, “just as you described and only two hours away.” He assures me he knows how to get there.

By 10 a.m., the trunk of the vehicle is crammed with so much equipment it sinks to the ground. When Albert puts the car in gear, with Annie and me in the back and Donald in the front, I hear metal scraping beneath us, but keep quiet.

We get lost, well ⦠several times.

And the maps, well ⦠they're the wrong maps.

But by noon, we're back on track.

Except noon is ⦠“Lunchtime!” Donald insists on stopping somewhere: “We can't work on empty stomachs.”

“No, we certainly can't,” I sigh in misery.

And what can I say when Albert detours from the main road to salute some relatives he has not seen for a while, saying, “It'll only take a minute”?

Nothing, I say nothing.

Â

It is not until the moment when daylight hesitates to bring on the evening that we drive through a little wood and find ourselves in a minuscule fenced-in lot.

From left to right: a small geodesic dome stands near a muddy embankment leaning into a murky pond holding a cloud of

mosquitoes. The whole area is lined with tall reeds and shrubs: not a single tree.

mosquitoes. The whole area is lined with tall reeds and shrubs: not a single tree.

“This is it!” says Albert triumphantly, gesturing toward what I would call an inclined swamp, much too small for my purpose.

Â

Take away the time to greet Albert's friend, the time to comment on the beautiful property, the time to unload the equipment, and it is getting dark. I barely have time to unroll the walk-cable away from the mud, to attach the two cavalettis to it, to anchor the cable to the bushes, and toâNo, there's no room for laying out the second cavaletti line, and nowhere to anchor it. As the Tirfor lifts the damn installation off the ground, a semiobscurity falls upon us and it starts to drizzle.

Donald and Albert help like underpaid marionettes. There is no time for me to explain anything. Albert invades my rigging with quick knotting demonstrationsâhe wants to show off his knowledgeâwhile the landowner scrupulously shoots the entire episode on video.

So much for privacy!

Â

It is pitch-black and raining hard when I finish assembling the balancing pole and am ready to step on the very loose wire.

Out of rage, I throw myself on the wire, do a forward somersault, and finish with two nocturnal backward rolls, all perfectly in line. “It has been four months since you set foot on a cable,” remarks Annie.

Â

The mud, the darkness, and the rain make the teardown a debacle and chase us back to New York City. The whole expedition has served absolutely no purpose.

Filled with bitterness and despair, I shrink my exhausted, wet, and freezing body into the fetal position in the backseat, with Annie's arms acting as a human safety belt. Eyes tightly closed, teeth tightly clenched, I remind myself, one after the other, of all the elements of past preparations, which are to meânow on the verge of tearsâso many proofs that the coup will not happen.

Other books

Mystic Militia by Cyndi Friberg

An Assassin’s Holiday by Dirk Greyson

The Chevalier by Seewald, Jacqueline

The Innocent's Surrender by Sara Craven

Private Bodyguard by Tyler Anne Snell

Fabulicious!: Teresa's Italian Family Cookbook by Giudice, Teresa

Migrating to Michigan by Jeffery L Schatzer

Man Eaters by Linda Kay Silva

La rabia y el orgullo by Oriana Fallaci

Memoria del fuego II by Eduardo Galeano