To Reach the Clouds (22 page)

Read To Reach the Clouds Online

Authors: Philippe Petit

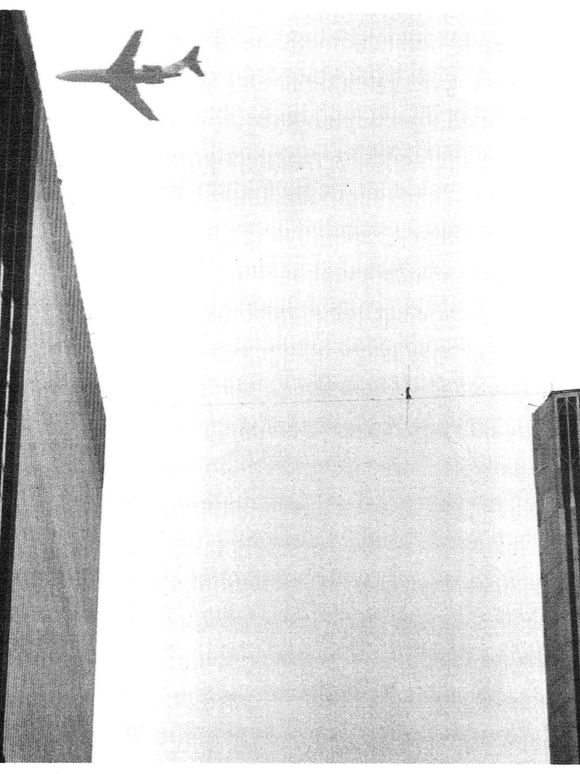

Shifting from the lying position to the sitting position, I notice a huge airplane passing above me, replacing for an instant the departed bird.

It seems someone is calling to me ⦠in English.

Â

Standing up again, I recognize I am at the top of the world, with all of New York City at my feet! How not to laugh with joy? I laugh with joyâand conclude the crossing with ecstasy instead of oxygen in my lungs.

Â

As I approach the edge of the building, a bunch of arms reach out to assist me in taking the last step.

Hey! I don't need help! I haven't finished my show!

I come about. Behind me, the arms pull back. I rendezvous with the long wire and perform the “torero walk,” gliding my feet, holding the pole away from my body, head high.

Near the end of the crossing, another voracious group of arms tries to grab me. An octopus! Smiling at the monster, I stop short of its reach and make another U-turn.

Next crossingâI'm absolutely no longer afraid of the wire, it is getting shorter as I stroll back and forth. Next crossing, I present the “promenade,” balancing the pole on my shoulder like a pitchfork, one arm dangling, as if returning to the farmhouse after a long day's work in the field.

Â

Someone is calling me â¦

Each new crossing begets a new walk, punctuated by fragile equilibriums, by genuflections, by salutes. Again, I sit down; again, I lie down.

Walking or motionless, I bathe in the sea waves, now on fire. Once more, this time under a ray of sun, I sit down in the middle of the cable to observe the world below.

By chance, and for the first time, my eyes focus on the octopus at the end of the wire. As I contemplate it fearlessly, it gesticulates and yells at my audacity. It is made of several uniformed men. Those men are angry.

How do you stop a wirewalker?

Â

Suddenly the shouting hurled at me reaches my ears, because this time, the words are in French. It is Jean-François, terrified by the threats of the policeâthey say they're going to loosen the tension on the wire, they say they're going to send a helicopter to snatch me from mid-airâwho has agreed to translate their latest message: “Stop right now or we'll take you out!”

For a second I despise Jean-Francois, but then I understand: he believes them.

Fascinated by a sudden wave of silence, I retreat into an endless balance on one leg, searching for the immobility that no wire-walker can ever find on a wire. Today, maybe, with the help of such prodigious height, I â¦

But I have trespassed long enough into these forbidden regions; the gods might lose patience. I offer my farewell to the New York sky: by running on the wire that shakes with allegresse, thus bringing down the curtain on the most splendid performance ever offered by a street-juggler/vagabond/high wire artist.

“Look! He's dancing, he's running!” scream my friends below, applauding my exit. They argue over the number of crossings: “He crossed six times!” “No, eight!”“He was on the wire for forty-five minutes!” “No, an hour!”

Â

I, a bird gliding back and forth between the canyon's rims, did not count the voyages, nor did I care to record the passing of time.

I land where I started, on the roof of the south tower.

The octopus grabs me violently. The unforgiving concrete hurts my naked feet through the thin buffalo-skin soles of my slippers.

My wrists are forced behind my back and clamped together by much-too-tight handcuffs. I am being read my Miranda rights.

“What?”

Not understanding a word of it, I force the arresting officer to repeat the formula several times, which helps me catch my breath and think ahead. New York policemen, Port Authority representatives, World Trade Center security personnel, emergency agents, and consultants from diverse agencies surround me so tightly I cannot move. They bark at me as they would at a stinky vagrant mutt. All the while, I am fighting for breathing space and for the right to be heard: “Listen! Listen!”

“That's it, let's go! You'll speak at the precinct, we've waited long enough!” So many pairs of arms, pushing and pulling, have no problem leading me harshly to the tiny stairwell.

Â

I resist, I shout: “No! There's going to be an accident, let me talk!”

Not in the mood to be told what to do, my arresting entourage pushes me more brutally away from the wire.

I scream, “Five seconds! Let me talk for five seconds! About the cable ⦠Something terribly dangerous can happen with the rigging!”

My escort remains deaf. Force is the only reason it knows, and it intends to use plenty of it to take me away.

Â

Out of nowhere, a tall construction worker wearing a yellow helmet cuts through the circle of my captors. He demands with authority to hear what I have to say. Raising his voice, he argues with the police before turning to me as the group falls silent: “Quick, explain yourself!”

“Well, it's imperative I loosen the tension on the cable. Right now, there's three-point-four tons, but if the towers sway, the tension will reach a terrible load and my cable will break ⦔

“Hell, if you think we give a shit about your fucking cable, we're gonna cut it with shears, that's what we're gonna do!” clarions someone who knows nothing about rigging.

“I don't give a shit about the cable,” I retort, attempting to persuade the imbecile, “but if you cut a wire-rope under tension, or if it breaks by overloading, you'll get a giant whiplash: some of us on this roof will be cut in half, and the explosion will hurl large pieces of steel into the void, defacing the building and killing quite a few people in the streets.” I pause and roar as dramaticallyas I can, “I'm warning you!” Then I point to everyone around in turn: “And

you, you, you, you

, and

you

are my witnesses!”

you, you, you, you

, and

you

are my witnesses!”

I'm being dragged to the tensioning device.

But I can't find the long handle. I remember setting it on a beam somewhere ⦠No, I must have hidden it. Where?

Turmoil!

I'm tightly surrounded once more. The arresting group, vociferous again, claims my plea to release the tension is an invention, an excuse to try to get back on the wire and escape! I wish.

Again, I'm pulled away, carried away â¦

“Wait! I remember! I hid the handle inside that pipe there, so no one would alter the tension during the walk.”

The come-along is fitted with its handle, and within minutes the wire is deprived of its precious inner tension. Soon it hangs loose and pitiful. It is so sad, the sky is about to weep.

Â

As I'm being propelled to the stairwell, it starts to rain.

The most perilous episode of the six-and-a-half-year adventureâwalk includedâremains what follows:

Savagely, I am being pushed down the steep, narrow staircase. Exhausted from the performance, hands cuffed behind my back, I am unable to control my balance; I can't slow my descent. Gathering speed, I hurl headfirst down the stairwell where it makes an abrupt left turn. I see my skull being shattered against the concrete wall. I try to steer my body away, but the inertia is too massive, my legs too weak.

With an inch before impact, a survival instinct restores electricity to my disconnected nerves. In a flash, I bounce back from the wall before touching it and scream my rage: “Hey! Careful!”

I try to scrape against the walls to slow the rate of my descent, but twice my barbaric captors shove me forward. Twice, yelling, I succeed in avoiding collisions with concrete.

Too tired to think straight, I am convinced the intention of my escort is to kill me.

Eyes wide open with fury, body covered with goosebumps, I concentrate on escaping the death sentenceâa much greater challenge than walking between the towers.

Â

Behind me I hear, “Is he resisting arrest?”

No, only death.

On our way to the elevator, we pass construction workers who erupt in applause and cheers when they see me. My entourage is not happy.

I'm delighted to be pushed into the mysterious police station under the towers; I have always wanted to see what it looks like

inside. Plenty of television monitors, plenty of buttons, plenty of cops shouting orders and counterorders about me. I do not try to understand what is being said to me. I let my fingers be rolled in black ink and pressed onto an arrest sheet, knowing it's a mistake; when you arrest a wirewalker, you should print his toes! No one notices that I cross my eyes as my mug shot is taken. Jean-François gets the same treatment.

inside. Plenty of television monitors, plenty of buttons, plenty of cops shouting orders and counterorders about me. I do not try to understand what is being said to me. I let my fingers be rolled in black ink and pressed onto an arrest sheet, knowing it's a mistake; when you arrest a wirewalker, you should print his toes! No one notices that I cross my eyes as my mug shot is taken. Jean-François gets the same treatment.

In the back, I see Albert arguing with an officer. Is he being arrested? Showing his cameras, he points at the ceiling and waves some I.D., obviously playing a journalist who's been stopped on his way to the roof. Clever. They let him go, and he passes by me without showing that he knows me.

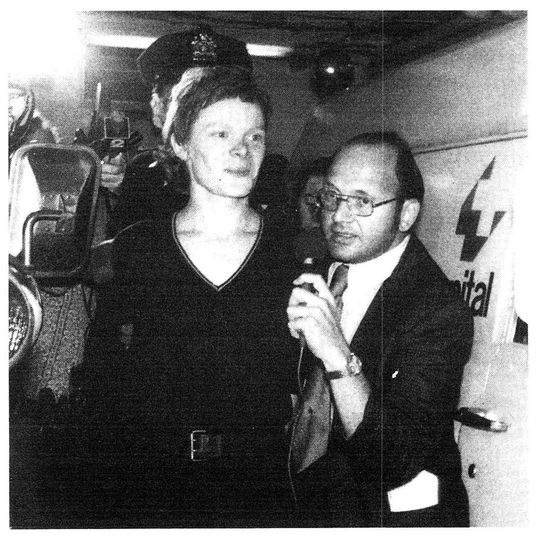

By the loading dock, my captors hurriedly squeeze me through a cluster of microphones and television cameras. My head still in the sky, I do not hear the questions but give my name and repeat, “

Immense happiness!

”

Immense happiness!

”

Why an ambulance, why blasting sirens, why a police motorcade? We arrive at the Beekman-Downtown hospital. Forced to lie face-down on a stretcher, I am rolled to a room labeled PSYCHIATRIC EXAMINATION. Jean-François is handcuffed to a radiator in the waiting room.

A young Pakistani doctor inspects the whites of my eyes and takes my pulse, counting in his native language.

Lying on my belly, handcuffed in the back, I keep asking, I keep begging, for something to drink.

The shrink enters. He's old, paternalistic, soft-spoken, andâI thinkâblinking far too many times a minute for a well-balanced human being. His head to mine, he whispers in the most articulate manner, “Whenâdidâyouâlastâdrinkâwater?”

“Are you mad?” I answer, raising my chin. “Do you know what I just did? I just spent months putting a wire without permission between the highest towers, I just astonished the world by dancing on that wire, right now the entire universe is talking about me, TV cameras are waiting downstairs. And all you want to

know is the last time I drank? You're completely insane!”

know is the last time I drank? You're completely insane!”

The man swivels on his stool, grabs his clipboard, and jots, “The subject seems perfectly normal, although exhausted and dehydrated.”

Â

A busty young nurse comes in with a paper thimble filled with half an inch of water. She leans over my handcuffed body; my eyelids almost caress her breasts when she brings the cup to my lips. “More!” I beg. She returns with a tray filled with more paper thimbles and helps me with the same naive generosity.

“That's enough, let's go!” my police escort interrupts after I swallow the contents of three mini-cups. Too late! My tongue lubricated by the water, I manage to drop a few elated remarks to the many journalists trying to interview me.

Now we have to run a gauntlet of reporters as we enter a building flanked by stables and labeled FIRST PRECINCT. I inhale the satisfying odor of horse manure. Maybe I can jump on a steed and gallop away to freedom. My captors are not ready to release a folk hero yet; they are still busy prosecuting a criminal.

They ask me the same questions they've already asked, they inscribe the same answers on the same forms, and again they put ink on my fingers and blind me with the flash of their cameras. Through the open windows, I hear the crowd of journalists shouting to be let in, demanding to talk to me.

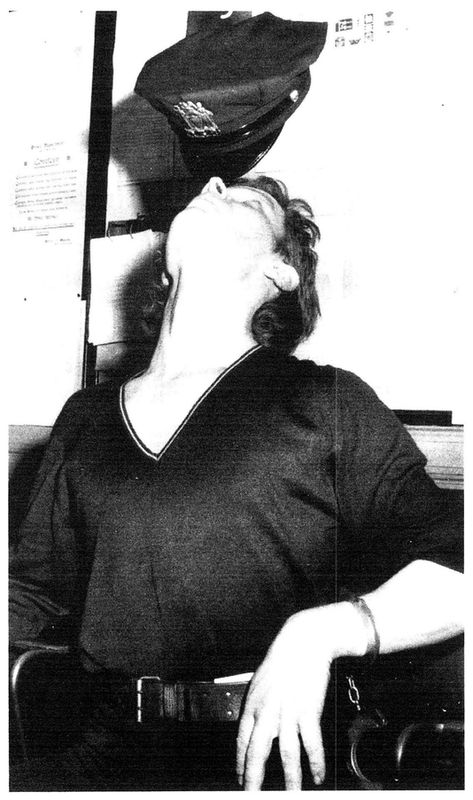

Chained to an armchair, I entertain myself by counting the orders and counterorders until my tough arresting escort disappears and leaves me in the hands of a group of admiring police officers. I notice a paper clip under my chair; I pick it up discreetly while scratching my ankle.

Finally, the press, now a mob, is invited into a waiting room; the police leave the door ajar. I see photo lenses sticking in; I hear the motor of a television camera spying on me. Using the purloined paper clip, I pick the lock of my handcuffs. With my free hands, I borrow by surprise the officer's cap and balance it on my nose. Behind the door, the journalists scream in delight; even the officer applauds. By the time he senses something is wrong, I have recuffed my wrists!

Police officers ask for autographs. They open the door wide: I'm being fed to the press.

I talk. I talk to no end, barely listening to the questions. “How old are you? How heavy is the balancing pole? Were you scared? Was it windy up there? How did you pass the cable across? So you did it for the publicity, eh?” When I announce that Jean-Louis is the exclusive photographer of the walks and has shot 16mm footage, each press member notes his name and number.

The officer allows one last question before he puts an end to my press conference. “Why did you do it?” the reporters chorus. I

answer without thinking, “When I see three oranges, I juggle; when I see two towers, I walk!”

answer without thinking, “When I see three oranges, I juggle; when I see two towers, I walk!”

Just before I'm taken away, a policeman tells me my sister is on the phoneâit's Annie's clever way of getting through to me. I expect tender words of congratulations, but instead I get a matter-of-fact monologue delivered in an insulting tone: “Listen. Stop giving everyone our phone number, saying Jean-Louis has a film. He has no film. And about the photographs, I don't know if you aware of it, but Albert took pictures too, and he sold them. Jean-Louis managed to sell his, but the whole thing is a disaster. He'll tell you. He's furious. We're all furious! See you. Bye.”

It is a disaster. I wanted to pass and repass in front of my eyes what went through reality so fast: the instants of the first steps, that most incredible moment of my life ⦠No film almost means to me no proof. I curse Jean-Louis, the authorities holding me, the press harassing me with stupid questions. I close my eyes and get back on the wire. There, at least, I'll be out of reach! I don't notice that new captors have come to get Jean-François and me. I don't hear the new convoy's screeching tires and blasting sirens, and I certainly don't care when the thick bulletproof portal of the New York jail called the Tombs slams behind me.

I am pushed into a huge, dark cage crammed with about fifty men, seated on the floor and standing. They have the same dark-toned skin, their faces are etched by the same fear, the same rancor, the same violence, and their bodiesâbarely covered because of the intense heatâoften show the same wounds. In a corner, an unsheltered hole in the floor is the toilet. The cell stinks. It is thick with smoke. Most bulbs are broken.

I'm the only white prisonerâalmost. My good friend Jean-François is still by my side. I had forgotten him!

We do not have to talk to know we both feel fear.

I take my sweater off and, putting it over my head like some of

the other prisoners, fake sleeping, leaning my bare back against the door. Jean-François lights a cigarette and tries to make friends by distributing the rest aroundâor does his entourage come to steal them one by one? Behind me, a guard approaches, rattles his keys, opens the door, throws a new prisoner in, and slams the gate shut. I scream in pain.

the other prisoners, fake sleeping, leaning my bare back against the door. Jean-François lights a cigarette and tries to make friends by distributing the rest aroundâor does his entourage come to steal them one by one? Behind me, a guard approaches, rattles his keys, opens the door, throws a new prisoner in, and slams the gate shut. I scream in pain.

I shout, “Open! Open!” not knowing how to say my skin is caught in the hinge of the gate. The guard moves away for a second, unsure whether I'm faking it. I scream and holler until he returns to the door, but he takes his time choosing the right key from his collection. He opens the door for a fraction of a second; I roll out of the steel trap and try to explore the long wound with my fingers.

What's all the noise, there's no blood!

is written on the faces of the people around me. To look like everyone else and to diffuse the pain, I force myself to smoke my first cigarette ever, but the pain is growing. I return to faking sleep, observing through my fingers the continual trade going on through the metal bars. A guard, a maintenance man, a kitchen employee, in exchange for money or cigarettes, keep passing food, drugs, messages inside the cage.

What's all the noise, there's no blood!

is written on the faces of the people around me. To look like everyone else and to diffuse the pain, I force myself to smoke my first cigarette ever, but the pain is growing. I return to faking sleep, observing through my fingers the continual trade going on through the metal bars. A guard, a maintenance man, a kitchen employee, in exchange for money or cigarettes, keep passing food, drugs, messages inside the cage.

Two hours later, Jean-François and I are called to the door.

Our new cage is minuscule and occupied by a skinny, wild-faced boy from Borneo. He asks if I am the man who walked between the towersâhow did the news infiltrate such a dungeon?âand begs me to hire him the next time I perform. He claims to be a contortionist, and laboriously hooks one foot behind his neck for me to appreciate.

A well-dressed man frames his face between the bars of our cell, introduces himself as District Attorney Richard H. Kuh, and announces I am going to be arraigned. He proposes to drop the charges (criminal trespass, disorderly conduct, endangering my life and that of others, working without a permit, disregarding police ordersâa litany of misdemeanors) in exchange for a small

display of my artistry to the children of New York in a city park. A few minutes of me juggling three balls under a tree in front of six kidsâas long as it's on televisionâis all the politician desires.

display of my artistry to the children of New York in a city park. A few minutes of me juggling three balls under a tree in front of six kidsâas long as it's on televisionâis all the politician desires.

Not understanding the subtleties of the laws, nor the powerful man's motive, I ask if the deal has direct political implications. The D.A. assures me it does not, and we shake hands.

Â

An hour later, Jean-François and I are taken from the Tombs and led through a maze of narrow underground passages to the courthouse. The D.A. stands by us in the courtroom. I'm given a front-row seat! Facing me, on a wooden shelf, a man of justice bored with life mumbles some gibberish to three young ladies with brown skin. Three prostitutes, one seductive and pretty, stretch their crying faces toward their accuser as if to bite him. In conclusion, the judge flutters his fingers in a gesture of disgusted ennui before he pounds the gavel. The three young women are brutally taken away to their new prison. I close my eyes.

Â

It's our turn. The judge wakes up. Sentence is given, all charges are dropped. The assembly applauds. The cops retrieve their hardware. Jean-François and I rub our wrists and smile at each other.

Other books

It’s a Battlefield by Graham Greene

Unbound by Cat Miller

Oliver Strange - Sudden Westerns 06 - Sudden Gold-Seeker(1937) by Oliver Strange

Sinners by Collins, Jackie

Skin Tight by Carl Hiaasen

Heaven by Randy Alcorn

I Am the Clay by Chaim Potok

Finding Sophie by Irene N.Watts

A Proper Companion by Candice Hern

Choke by Diana López