To Reach the Clouds (7 page)

Read To Reach the Clouds Online

Authors: Philippe Petit

Yves misses shooting the scene, of course.

Â

Â

Â

The weather continues to mimic the group's mood: the sun is shining. We all rush out to the big meadow.

On the tall grass, with wooden stakes and yellow polypropylene ropes, I set the exact perimeters of the two towers facing each other corner to corner, 138 feet apart. Everyone helps.

“Okay, everybody, behind Jean-Louis!” I order, as my friend prepares his bow and arrow.

Jean-Louis picks up a plank he has brought along. Two nails are already half driven into it, three feet apart, and he proceeds to wrap a very long piece of twine around and around the nails, keeping it tight. When he has only a foot of twine left, he swiftly knots a series of clove-hitches at both ends. Then he pulls out the nails, releasing a perfectly made traditional bowstring.

I am impressed. “Where did you learn that?”

Without missing a beat, and without pausing as he hooks the string to the bow, forcing it into a majestic curve, Jean-Louis whispers, “Yes, well, some people do their homework!” Then he takes aim from the “north tower” and hits the center of the “south tower”: a bull's-eye. (He boasts that he's been practicing for days, aiming at old ladies in the castle gardens at St.-Germain-en-Laye.)

By happy accident, Yves gets it on film.

But when we tie the 300-foot fishing line to a minuscule hole drilled behind the arrow's feathering, the exercise turns disastrous. After ten minutes of carefully arranging the line in a zigzag behind him, Jean-Louis silences us, takes a deep breath, concentrates, aims, draws, and shoots. And the arrow falls ⦠at his feet. That is not on film.

I can't help crowing, “See, I told you it would never work!”

We stay well past lunchtime, trying countless improvements, arguing all the while. Winding the line around a spool that turns freely on a handheld pencil gives a much better result, but still the dead weight of the line makes Jean-Louis undershoot his mark by half.

Once more, Mark saves the day. Borrowing from an ancient fishing technique of his country, he breaks off one of the spool's flanges and sands it smooth. The line can fly off freely in the axis of the pencil. The next attempt is almost a hit. With practice and minor improvements, Jean-Louis should have no problem.

Amid the applause, I yell, “I knew all along the bow and arrow was the solution!” and Jean-Louis laughingly throws me to the ground.

Mark holds the improvised spool as Jean-Louis prepares to shoot â

a still from the 16 mm film

a still from the 16 mm film

After a delicious salad fresh from the farm's garden and Annie's

mousse au chocolat

, I drag the group outdoors again, ignoring their pleas for a nap.

mousse au chocolat

, I drag the group outdoors again, ignoring their pleas for a nap.

I start with the circus installation. Accompanied by Nino Rota's music from the scratchy record-player, I perform a brief high wire anthology that includes, in addition to my distinctive walks, the bicycle, the unicycle, the chair, juggling, and somersaults. I reach the ground by walking down the slant wire without balancing pole. “Bravo!” shout my friends.

An appetizer.

Without taking a break, I run to the Hundred Meters, climb on the departure X, grab the waiting pole, and start walking. The cable being properly guy-lined by four well-tightened cavalettis, I reach the arrival X without once stopping.

It takes me only three minutes.

Â

I climb down and impatiently start removing all the cavalettis.

A moment later, I'm back on a naked wire that is free to oscillate.

I grab the pole. I walk. After twenty feet, the cable begins to vibrate. I slow down.

As I progress, the undulations amplify. By midwire, the cable dances an agitated jig. I pause after each step, but keep going. I pass the dreaded middle, even though the out-of-control cable tells me to stop. Anchored to the wire by my toes, riveted to the arrival X by my eyes, I stand there fighting waves two feet high, three-foot lateral swaying, and the jerky, invisible but very palpable rolling of a wire gone berserk.

Yves is filming from a tripod, although the cable is moving so violently that I keep disappearing from the frame.

I let myself be carried in all directions, make myself one with the wire, dead weight, not even breathing. The cable calms down, and soon I am able to resume walking, one step at a time, until eventually, exhausted, elated, I conclude the crossing.

Â

But that's not it.

Ignoring the congratulations of my friends, I shout, “We have

barely enough time, help me!” and direct them to replace the four cavalettis on the cable, which I then feverishly retighten.

barely enough time, help me!” and direct them to replace the four cavalettis on the cable, which I then feverishly retighten.

“Stay close to me!”

I jump back on the wire. I walk firmly to the middle and wait. A few feet behind me, the group gathers under the wire.

“Quick, loosen the tension on the cavalettis, starting with the closest one!”

“Done!” yells Jean-Louis.

The cable starts dancing again, in an even more brutal, erratic way than before; this time, instead of swinging freely, it's carrying the loose cavaletti ropes.

I take the punishment.

“Okay, now move the ropes! Come on, move the ropes! Make them shake!”

First Jean-Louis, then Mark, then everyone gently shakes the ropes. I follow the wire's awkward dance.

“More! Harder, harder!”

My friends follow my orders, keeping their eyes glued to my vibrating silhouette.

“Come on! Jump on the ropes! Hang on them! Take the wood there and bang on them!”

Timid at first, the group gradually throws itself into the game.

“Harder! Harder!” I shriek. “What the hell are you afraid of? Come on! Try to throw me off the wire, damn it!”

Jean-Louis shakes his rope violently, and Mark follows, kicking it with his feet. Soon everyone is jumping up and down, hitting the ropes, screaming and laughing, until I plant one end of the pole in the grass and beg for mercy.

Since I no longer have the use of my legs and arms, I let my body be carried back to the house. The sky has already fallen asleep.

Â

Â

Â

At Annie's suggestion, in the early morning I drive to the village

boulangerie

and bring back a basket brimming with warm croissants. Then I announce my decision to stop filming the coup.

“Either we do a bank robbery, or we do a film about a bank robbery. We cannot do both,” I say. “I have decided to do a bank robbery.”

boulangerie

and bring back a basket brimming with warm croissants. Then I announce my decision to stop filming the coup.

“Either we do a bank robbery, or we do a film about a bank robbery. We cannot do both,” I say. “I have decided to do a bank robbery.”

Jean-Louis beams.

Yves understands. He picks up the camera and, walking backward with his soundman, films their exit from the house and from the coup.

Â

But where is the cameraman?

Someone screams. It's coming from the big meadow.

Still chewing on croissants, we run outside to find the unfortunate fellow lying on the ground under the Hundred Meters. “I had to give it a try!” he confesses, grinning through his pain.

A couple of hours later, he returns from the Nevers hospital sporting a superb cast and thanks us warmly for our unique hospitality. “Wait!” I say. I go into the house and come back with my New York crutches. “Here, it's a gift, don't lose them!”

Â

Â

Â

I leave everyone else to depart when and how they wish, and Annie to clean and close the old house and hitch a ride back to Paris.

I'm already in my truck, rushing back to Germany. I munch on candy bars and pee in a jar, determined to drive the thousand kilometers nonstop.

“Hi, Francis! Thanks for the money! Bye! See you in New York! Got to go!”

On the way back to Paris, I force the truck to its limit, stopping only for gas.

Â

Â

Â

The phone rings and rings.

“What? Tomorrow morning? You're sure? Oh, that's very nice, thanks!”

It's Jean-Louis, offering to drive Mark and me to the airport. I look at the clock and realize that, thanks to exhaustion, I've just slept twenty hours straight. Nothing is ready. I panic. But I agree to have a long lunch with Paul the Australian, who is just in from London. A thin fellow with short hair, he is as focused and steady as he was during the Sydney walk. He takes his time questioning me.

Patience is rewarded: two hours later, Paul is in.

Â

Â

Â

During the flight, I interrupt Mark from the movie to help stick address labels on a giant stack of my promotional brochures. “After WTC, I'll need those.”

Half awake, I ruminate for a rare moment about Annie.

Since long before Vary, she has been angling for an invitation to New York, using tenderness, blackmail, the past, the future, threats, insults, and tears. How disrespectful, how unloving I have been, to evade an answer. But I need absolute detachment, complete freedom. I must be a castaway on the desert island of his dreams, forgotten by all and forced to survive on his wits.

Â

As the plane comes in for a landing, I see through the dirty windows my twin towers, waiting for me.

My third arrival in America.

Mark has just passed through customs unchallenged. Why do I always attract suspicion?

“Open up!” orders the towering customs agent.

“What's all this?” he exclaims, eyeing my three battered suitcases brimming with equipment and pointing at the long cylindrical package I can hardly pick up.

Like an amicable salesman, I lift each item slightly in turn,

intoning, “Polypropylene ropes, hemp ropes, nylon ropes. Small block-and-tackles with two sheaves, large block-and-tackles with three sheaves. Steel wire-ropes of various diameters. Pulley-blocks for fiber ropes. Safety belts. Construction gloves. Ratchets and monkey wrenches. And, oh, I forgot, a long balancing pole in four sections, complete with assembling inner sleeves!”

intoning, “Polypropylene ropes, hemp ropes, nylon ropes. Small block-and-tackles with two sheaves, large block-and-tackles with three sheaves. Steel wire-ropes of various diameters. Pulley-blocks for fiber ropes. Safety belts. Construction gloves. Ratchets and monkey wrenches. And, oh, I forgot, a long balancing pole in four sections, complete with assembling inner sleeves!”

“What's all this for?” inquires the frowning giant.

“Oh, nothing. I'm a wirewalker, and I'm here to put a cable between the twin towers of the World Trade Center!”

With a long, loud laugh and gesture toward the exit, the agent replies, “Sure! Welcome and good luck. Next!”

Being of proper upbringing, I smile and murmur, “Thank you.”

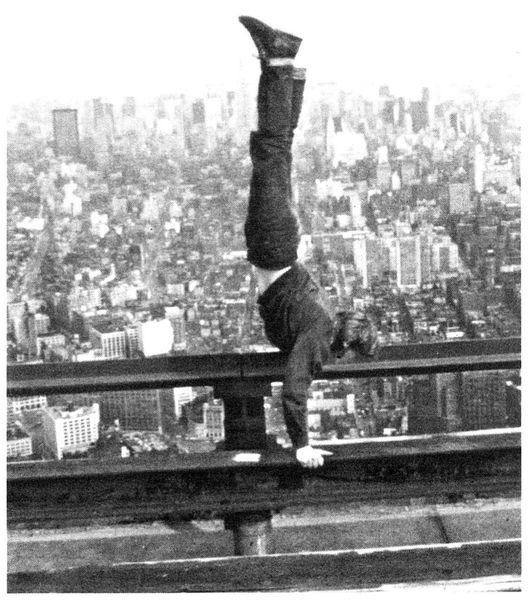

The next day at lunchtime, Mark and I sneak to the roof of the north tower without a problem.

He takes in the panorama, unconcerned by the void, while I note the changes in the construction site and work on my handstand.

Â

Suddenly, a policeman appears behind us. “Hey, you two, come over here!”

We freeze.

“Do you have any I.D.?”

Eager to prevent Mark from saying anything, I volunteer hurriedly, “No, we don't have any idea! We came here with no idea at all, actually; we just came for the view.”

The officer looks at me strangely and turns to Mark: “And you, you have an I.D.?”

Mark opens his mouth, but again I interrupt before he can utter a word. If this cop thinks we have an idea, he must have a suspicion about the reason for our presence. Maybe he has seen me sneaking around here before, maybe he knows everything. I become agitated, convinced that my answer means life or death for the coup. “No, officer, he does not have any idea either,” I say. “He's just a friend, a friend with no idea. Actually, it was my idea to ask him to accompany me to see the view, but you can't really call that an idea. When we're together, it's always me who has ideas. I'm always full of ideas. But today, I assure you, we don't have any ideas, no ideas at all!”

The cop's amusement at my speech and heavy French accent gives way to impatience. He pulls out a notebook and pen. “Come on, guys, I need an I.D., now.”

Â

Now that I am silent at last, Mark tactfully explains to me what an I.D. is. We show our passports. The policeman writes down our names and New York address. Like a juggler, he flips shut the pad's heavy cover with a twist of the wrist. With the other hand, he flicks the pen closed in mid-air and returns it to a groove in his leather holster, like John Wayne. “Get out of here! And don't even think of coming back to the roof. I don't ever want to see you guys around these towers again. Is that understood?”

Other books

Erin's Way by Laura Browning

Deep by Bates A.L.

Flirting with the Society Doctor / When One Night Isn't Enough by Janice Lynn / Wendy S. Marcus

In Between by Kate Wilhelm

What Belongs to Her (Harlequin Superromance) by Rachel Brimble

The Rookie a Studs in Spurs Deleted Scene by Cat Johnson

Risque Pleasures by Powers, Roxanne

What Distant Deeps by David Drake

The Case of the Sharaku Murders by Katsuhiko Takahashi

Death Sentence by Roger MacBride Allen