To Reach the Clouds (3 page)

Read To Reach the Clouds Online

Authors: Philippe Petit

I am in a huge store buying all the different postcards of the twin towers. (Some fall into my bag by accident.) I could stand here comparing them for hours, but Jim Moore is on time.

I decide to infiltrate the same tower at the same hour as yesterday. My companion is sure we're going to be arrested.

Taking the same haphazard itinerary, running into the same situations, surprise encounters, escapes, and miracles, we emerge with the same success on the rooftop, which is again deserted.

Jim's face whitens as he gazes at the other tower. The altitude has hit him. Or is it the project's magnitude?

I catch him mumbling to himself, “You're insane!”

“Extraordinary!” I whisper, radiant.

Â

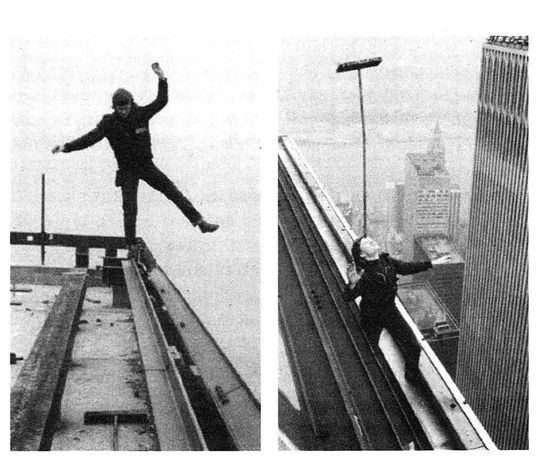

Sitting on a beam at the strategic corner, I point at the taunting roof facing me: Jim snaps the shot that will, until walk day, symbolize le coup, keep it alive and hold me prisoner ofâyesâthe insanity

extraordinaire

to which I've willingly shackled myself.

extraordinaire

to which I've willingly shackled myself.

Indulgently following my directions, Jim moves around the roof, taking pictures of construction areas and close-ups of the equipment. Meanwhile, I lean over the flat bar of the upper edge. Again I consider climbing down to the lower ledge, where the sheer aluminum cliff initiates its vertiginous descent.

Yesterday I dared not. Today I must.

It cannot be done all at once. To overpower vertigoâthe keeper of the abyssâone must tame it, cautiously.

Brushing aside any thought of climbing down to the lower ledge, I step up onto the flat bar that runs thigh-high along the corner of the roof's upper edge, and begin to balance on it. It's a piece of metal half an inch thick by six inches wide. It feels a bit like a cable under my feet. I manage to hold my balance on one leg for a second or two.

“Jim! Quick!”

A photo is taken. But I did not enjoy this balance. It was somehow faked, timid. I felt overpowered by the sky from all sides. Encouraged nonetheless, I step over the flat bar with extreme caution. I climb along one of the inclined columns, focusing on my hands and feet, until I reach the elevated steel gutter that forms the definite rim of the building. Where the void reigns, almighty. Where the unreachable rampart of the other summit can be seen rising in all its splendor. Oh! I am terrified. It's the towers and me, on a background of clouds, of blue air. Cruel confrontation. The wind, the howling depth prevent me from talking to them, them from hearing me. They are masterful, they rule. I am insignificant. Mid-air battle. I force my unwilling body to lean over, over this ⦠this absence of the tangible, this ⦠Ah, yes, my mind registers, far, far down, the ground, the streetsâbut my eyes refuse. Yet I breathe in voluptuously the unknown that eddies below. I keep fighting.

“I have one picture left,” announces Jim. In order to look up at him, I must first hold on to the structure, or I chance being pulled into the bottomless canyon.

I notice an old bristleless broom at his feet: “Pass me the broom.”

“You sure?”

“Pass me the broom!”

I let go of the column in order to position the broomstick in equilibrium on my forehead. I take my fingers away, and the broom stands freely, balancing in the breeze. For how long, maybe the count of four heartbeats? Then it regains its independence, leaning away. I twist my neck. I bend sideways. The broom and the funambulist together fall slowly into the jaws of the wind.

No!

I resist the fall.

Again I bring the unwilling, awkward prop to the vertical, balance it another second, and quit. I have won. No one will ever know I slipped the tip of my left shoe under the gutter to help hold myself steady during the delicate balance.

Â

It is all too grand down there, up here. I will have to come back, again and again, a hundred, a thousand times. To inhale the altitude, to savor the ever-growing depth, to find myself alone with the towers, nose to nose, before I am capable of challenging them. For the moment, they are so much more solid than I am.

Â

Jim is wary of the time already spent. The sky grows menacing; we wrap it up.

As we climb through all shapes of clouds, I press my nose to the window, fascinated, and wait.

The cabin floor is gently brought back to horizontal as the plane attains cruising altitude. I reach for my collection of postcards and the freshly printed photographs, which I review carefully until I doze off.

Â

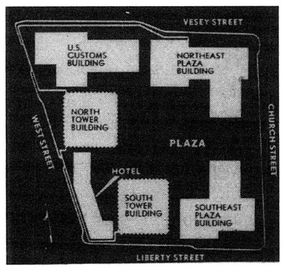

Suddenlyâa geyserâan idea surges and wakes me up: all the equipment needed for the coup is already on the roof! All I have to do is sneak in with a few tools. Feverishly, I spread the pictures on the tiny tray in front of me. That wire over there, wrapped around the crane's winch, will do as a walk-cable. I can link a couple of the chain-hoists scattered around and create a tensioning device. The cable clamps I need, I'll take from these lines here, securing this pylon. There's rope everywhere, enough for making cavalettis, the vibration-reducing guy-lines I'll need to tie to the walk cable. And for a balancing pole, I can use one of those metal pipes over there, why not.

Â

The airline stationery I requested is brought to my seat. It reads, “Air France,

en plein ciel, le

____.” Not bothering to fill in the date, I cover a dozen sheets with frantic notes, sketches, and lists, establishing the first rigging plan. Nothing is left out. I'll need someone to help on my side, and two people for the other tower.

en plein ciel, le

____.” Not bothering to fill in the date, I cover a dozen sheets with frantic notes, sketches, and lists, establishing the first rigging plan. Nothing is left out. I'll need someone to help on my side, and two people for the other tower.

Next, I write Jim a note: “I'll be back in a couple of months to execute the coup.”

Done.

As soon as I get off the plane, I mail Jim's letter and rush toward the suburb of St.-Germain-en-Laye. I reach an old house, run up five flights of stairs, and bang on the door: “Police, open up!”

No response, but the door slowly opens by itself. As I enter, it slams behind me. Two fingers imitating the barrel of a handgun hit me in the back: “Hands up, freeze!”

That's Jean-Louis.

Â

We were sixteen when his favorite activity, photography, and mine, funambulism, caused us to meet. Unlike other kids, Jean-Louis was encouraging and respectful as he saw me install my first wire and watched me practice between two majestic cedars in the backyard of the local youth hostel. After much observing, he asked if he could take pictures. I asked if he would allow me into his darkroom to observe printmaking. Fascinated by each other's “professions,” we became friends.

It was Jean-Louis who threw the ball across the towers at Notre-Dame, helped me rig all night, took pictures of me waiting past dawn, and shared his exclusive reportage of the performance with the world.

Â

My companion from adolescence has barely changed. His tall, broad-shouldered frame still sits upon two solid legs ready for action. His piercing eyes, constantly recording, light a serious face that is nevertheless quick to melt into an engaging smile.

“Go ahead, tell America!” teases Jean-Louis.

“Wait! I have to see if you're still in shape! I don't share my coups with klutzes!” I position a stool in the center of the room, and Jean-Louis ten inches away. “Go for it!”

With no preparation, feet together, Jean-Louis leaps over the obstacle, and lands softly. Then he pulls out an immaculately folded hand-kerchief, opens it, pats the sweat from his forehead, and refolds it meticulously before he buries it in his pocket, deadpan.

“Now we're talking!” I grin, and proceed to describe my fabulous project â¦

Soon Jean-Louis interrupts. “Who are you kidding? Your fabulous projectâit's a joke. You don't know what's on the other rooftop. You don't know what time the construction crews start and quit work. You don't even know the distance between the towers! Sure, I'll do the coup with you, but you've got to work things out. And the windâyou thought about the wind?”

“The wind? Yeah. Don't worry. So ⦠you're in?”

“Sure.”

Â

True, I don't have a plan.

Then Annie resurfaces.

Annie, whom I have not seen for six months.

Annie, who knows me better than anybody.

Annie, who was at my side during my discovery of the wire.

Annie, who encouraged and advised me.

Annie, often withdrawn, occasionally shy or suddenly blooming.

Annie, who listens.

Annie, who does not hesitate to cut through my brilliant discourses with sharp criticismsâcausing an immediate rift until the next reconciliation.

Annie, whose large green eyes move me when she looks around, taking in everything.

Annie, who holds me. Our silhouettes are similar: not too tall, not too firm. When we embrace, we look like two kids plotting our next piece of mischief.

Â

At the counter of the brasserie where we rendezvous, Annie leans her elbows on the zinc, creating with her long, thin fingers a sort of woven basket within which she delicately sets her pale face, framed by wavy brown hair.

She's observing me.

Feverishly, I announce my next illegal walk.

Annie listens, entertained. She's obviously proud to have succeeded at last in adopting a distance from me.

Â

She bids me adieu.

I promise, “

à bientôt,

” because the coup cannot happen without her support.

à bientôt,

” because the coup cannot happen without her support.

Insensible to the passing of time, I browse through bookstores of all persuasions. When permitted, I search the archives of architectural societies. For days, slouched in a plush armchair of the dark, muffled, imposing Bibliotheque Nationale, I dig and probe. I extract all the information Paris is withholding about New York's World Trade Center. As my knowledge of the twin towers grows, so does my collection of magazine stories, newspaper articles, scientific studies, and photos.

Now Annie joins me, and within two weeks our harvest proves bountiful.

My ever-expanding file soon needs a container; the container needs a title. I transfer three black capitalsâElzevir, I recallâonto the spine of an orange photographic-stock box found in the garbage: the dossier “WTC” is created.

Overnight, I no longer speak of “the twin towers” or “the World Trade Center.” Instead, I refer to my idée fixe by the new tongue-snapping acronym WTC.

And each time I open the orange box, the evidence jumps out: the WTC I'm getting to know is a building project soon to be completedânot the three-dimensional, pulsating organism whose steel skeleton I need intimate knowledge of. For that, I must go back.

I must venture again into the belly of the beast.

Other books

Unexpected Fate by Harper Sloan

Tracking Time by Leslie Glass

Space Cadets by Adam Moon

Two for Flinching by Todd Morgan

Death Among The Stacks: The Body In The Law Library by Louise Hathaway

Blythewood by Carol Goodman

Knights and Kink Romance Boxed Set by Jill Elaine Hughes

A Peculiar Grace by Jeffrey Lent

First You Fall: A Kevin Connor Mystery by Scott Sherman

Educating Ruby by Guy Claxton