Time & Tide (2 page)

Quiet Days/Quiet Nights

NANTUCKET IS DRENCHED WITH MEMORIES of the whaling days and the nineteenth century. It is sodden, to tell the truth. The high school team is “The Whalers,” the Nantucket Historical Association Library is 90 percent nineteenth century, as is the Folger Museum, and this history has been logoized and commercialized by the merchants, the Chamber of Commerce, guest houses, etc., to an excessive degree.

Which is not to say it wasn't an interesting time. With most of the male population at sea, the island was controlled and managed almost exclusively by women. They ran local commerce and dominated politics. It was a highly stratified, nuanced, and complex society in which religious issues roiled, social groups parried one against the other, and sexual forces undoubtedly bubbled under everything. (“Nervous? I will spend the night with thee. 25 cents,” ran an ad in the paper. A type of ceramic dildo imported from Asia called “He's at home” was a common domestic item.) Nevertheless money and business were king, and the island hummed. An interesting time for many reasons, yet not, of course, the only interesting time.

DESPITE MR. MOONEY'S remarks about direct air service from Boston and New York, the Nantucket airport in the fifties was small and simpleâa kind of shed and two short runways which crossed each other, one running roughly north-south, the other east-west. It was agreed there was no need for a tower or the complicated and expensive business of an instrument landing system, although the island, and that particular part of the island especially, was famous for its dense fogs, which could appear without warning and with remarkable speed. Commercial air service, which had been minimal at best, almost disappeared after 1958, when a Northeast Airlines prop DC ended its scheduled run from New York by crashing in the Friday night darkness before it reached the runway, killing twenty-four people and leaving ten survivors (one of whom, Jack Shea, a lawyer, was a friend of long standing; he survived, but couldn't remember much when they found him crawling around in the moors. Years later, he still couldn't recall the details).

In the sixties the runways were lengthened to accommodate jets, the tower was built, and radar/instrument landing was installed. Eventually it became a modern airport, and both commercial and private flying increased steadily through the years until it was busier in summer than any other airport in Massachusetts, including, at times, Logan in Boston. But I'm getting ahead of myself.

AFTER COLLEGE MY girlfriend and I got married. We lived in New York City, but continued to come to Nantucket every summer for twelve years. (Except once we went to Martha's Vineyard and didn't particularly like itâit lacked the ubiquitous ocean smell, the saltiness, the moors, the simplicity and spareness of its smaller sister, the “faraway island,” as the Indians called it.) We had enough money to stay all summer long, and enough so we didn't need jobs. We rented different houses in Nantucket along Polpis Road. There weren't all that many houses out of town in the sixties. Most nights, if you sat out on the porch, let's say, you might see the distant flicker of headlights and hear a car on its way to Pocomo or Quidnet or Wauwinet every hour or so. If Nantucket and 'Sconset were dense, close-packed towns, the rest of the island was mostly bare, sparsely populated, and, as a result, quite private. We relished the quietness, took the children (two little boys) to the South Shore with its dunes and deep white beaches almost every day, and spent the evenings reading. The stars at night were spectacular. The clear air and the lack of ambient light opened up the heavens and seemed to bring them closer. Shooting stars were commonplace all summer long.

An interest in the stars and their movements had been a part of Nantucket's culture for a long time. In the nineteenth century virtually everyone owned a telescope with which to search the ocean for sails, or confirm the names of ships coming into the harbor. The same telescopes could be pointed upward.

Aside from the study of astronomy, there is the same

enjoyment in a night upon the housetop, with the

stars . . . there is the same subdued quiet and grateful seriousness . . .

So sayeth Maria Mitchell in her diaries, and I felt the same way lying on various lawns with good binoculars, and eventually with a Questar, a compact, highly sophisticated catadioptric telescope I'd borrowed from a movie director I knew.

My love for astronomy was born on that island . . .

the spirit of the place had also much to do with my

pursuit. In Nantucket people quite generally were

in the habit of observing the heavens, and a sextant

was to be found in almost every house. The landscape

was flat . . .

Maria's interest in science began with her father's lessons. She became an expert in the adjustment of precision chronometers while still a child. As a woman she discovered a comet and was awarded with a medal from the King of Denmark. She served as a librarian at the Atheneum for a salary of $100 a year. She helped arrange the Lyceum lecturesâThoreau, Agassiz (the Swiss naturalist and glaciologist), Audubon, Emerson, and other notables whom she convinced to make the trip and come 'round Brant Point. Eventually she became a professor of astronomy at Vassar College (at $800 a year). There exists in Nantucket a Maria Mitchell Association and Observatory to this day, in tribute to an authentic hometown heroine.

During the sixties my wife, Patty, our children, Dan and Will, and of course myself took full advantage of what was still a quiet, calm island. We rarely went to town, although when we did it was still pleasant to visit the library, go to the bookstore, buy a good wool sweater at the Nobby Shop for a fair price, have a drink at the Club Car, or buy a raffle ticket from a lady at a card table in front of the Catholic church. As the streets became more crowded from one summer to the next, we barely noticed.

Outside of town we could walk for miles over the moors or along beaches without seeing a soul. The South Shore dunes were private enough that the occasional nude sunbather might be startled into grabbing his towel to cover himself when a certain State Motor Vehicle Bureau officer (uniformed and armed in the state of Massachusetts) would appear out of nowhere in a specially accessorized low-flying Piper Cub and shout down from above, “You are under arrest for indecent exposure. Stay where you are.” Of course the putative offenders always took off pronto and no one was ever arrested. The local police quite sensibly ignored calls from the plane. This same uniformed individual did not endear himself to the board and members of the Sankaty Head Golf Club when he insisted that every golf cart be fitted with headlights, license plates, and everything else needed to meet state motor vehicle regulations because the carts crossed ten feet of a state road between holes two and three. (The club appealed in court and won.) Nantucket has always had oddballs and characters of one kind or another, and local oral history has not forgotten them.

But as quiet as Nantucket seemed to be, changes were under way. And perhaps the very big changes on the mainlandâe.g., the civil rights movement, foreign wars, “changes in the wind,” etc.âmade it harder to appreciate the importance of the gradual takeover of downtown property by a group of businessmen with a master plan. They began buying in 1964 and anticipated a complete restructuring of the waterfront starting in 1966 with the aim of replacing the dwindling fishing industry activity with an economy based on tourism, an extensive yacht basin, and downtown retail outlets to serve the very rich in addition to the day-trippers. Good-bye to the old Five and Ten, the Upper Deck (a favorite bar of the locals), the Ocean House where I'd played piano. (What a gig that had been! Five college waitresses, all cute, who would gather 'round the piano at closing time, each with her one free drinkâBrandy Alexanderâlistening to me play “Tenderly,” “Blues in the Night,” “The Little White Cloud That Cried,” or whatever else they requested. Severe temptation, and of course I gave in. I was nineteen years old and completely girl crazy.)

Sherburne Associates had a plan, and even those who were against it had to admit it was well executed, and that off-island money began to flow into the island economy. It was pointless to revile Sherburne, or Mr. Beineke, the so-called Green Stamp King whose plan it mostly was, because change was inevitable. The old piers and wharves were falling to pieces, for instance, literally rotting away. The waterfront was a danger, and not only to children. Sherburne built a new waterfront, starting with Straight Wharf at the foot of Lower Main, and ending with a huge modern yacht basin with hundreds of slips and all necessary support services. The island of Nantucket, with its open spaces, beautiful and well-protected harbor, architectural treasurers, beaches and salt marshes, was essentially powerless to resist change. And it was a plum. Jet service from New York or Boston in a matter of minutes. Charm. Quaintness. Quiet. The gentle rhythms of small-town life. No one, including Mr. Beineke, could have foreseen what would eventually happen.

Settling In

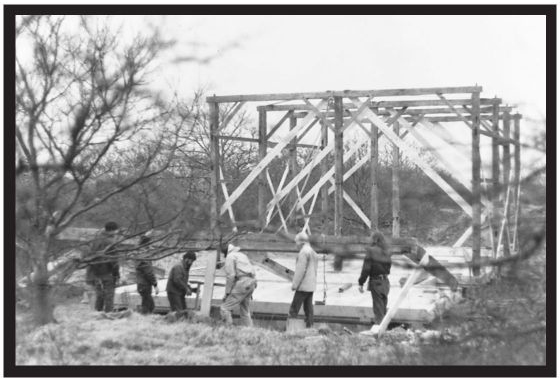

IN THE LATE SIXTIES WE LIVED IN BROOKLYN and I occasionally made money as a “script doctor” for the Hollywood studios. My biggest job was an original script for Paramount. They never made the movie, but I was paid thirty thousand dollars. My wife's uncle gave her a matching gift and we thought about land and a summer house. We had in fact admired a certain large area off Polpis Road called Quaise, almost all of it owned by one man, and had asked him, every year, to remember us if he ever wanted to sell a few acres. Things came together magicallyâthe movie money, the match, and the arrival of the landowner's first son at the gates of an expensive college. We bought a lovely bit of land that contained a mini forest, a beautiful salt marsh behind which could be seen the southern end of Polpis Harbor. We could walk down to the water on our own land. I hired a six-foot -seven-inch bearded back-to-nature M.I.T. engineering graduate to oversee a bunch of hippie carpenters. An architect friend purchased an old tobacco barn in the wilds of western Pennsylvania, dismantled the frame with some help from a nearby hippie commune, figured out how much siding would be needed, had it cut at a sawmill, and brought the whole thingâ hand-hewn chestnut beams and raw white oak boardsâon a semi which came around Brant Point in late '68. I drew up a design, the architect did the specs and solved the “fenestration” problem, and by the spring of '69 the house was almost finished. And so, unfortunately (to put it mildly, and for reasons that had nothing to do with Nantucket), was my marriage. The divorce was as amicable as I suppose it was possible to be. My wife kept the brownstone in Brooklyn, and I got Nantucket.

The Barn going up.

Somewhere in his enormous body of work, John Updike writes, if I remember correctly, that the ideal size of a community is five thousand. Nantucket's year-round population was stable, as I said before, for a very long time, but in the early seventies it began to move toward Updike's magic number. It was a different kind of community from the small-town/semi-pastoral atmosphere in which Updike spent his boyhood. You're thirty miles out to sea, for starters. I don't have much nostalgia for Nantucket in the seventies. Personally it was a tough time both emotionally and economically. I was a writer, after all, and, to make it worse, a literary writer. I left Brooklyn with three hundred dollars, no job prospects, and an unheated, unfinished barn on a remote island my only possession.

The population included people who worked for the water company, the telephone company, the town itself, etc., as you would find in any town, and an awful lot of people who served the summer people in one capacity or another, building or taking care of houses, running the hotels and guest houses, and who had to make enough in three and a half months to support themselves for twelve.

In addition there were a lot of odd people, nonconformists, wounded people (like myself ), dropouts, fantasists, hiders from reality, wanderers, loners, weirdos, and characters. It was a kind of halfway house for some, and some never left.

I've already mentioned the man who worked at the State Motor Vehicle Registry office. A thoroughly nasty guy. But then there was Sam, a cheerful, good-hearted simpleton who hung around downtown with his beloved pet rabbit Floppy, and whose Deep South black accent was almost indecipherable, but whose smile was not. He was the town fool, essentially, and the town took care of him. (He never begged, but he got by.) It was a simpler time, as they say.

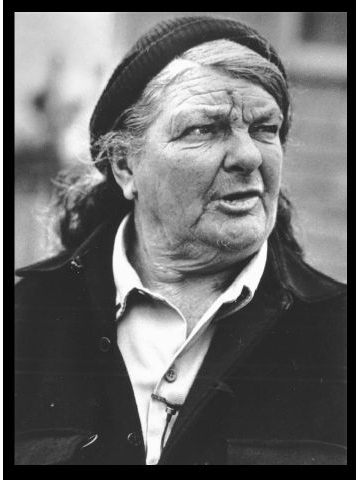

Perhaps the best-known character was Mildred Jewett, known as Madaket Millie, who was born on the island in 1910 and raised on a small farm on the west end. Her mother had disappeared, her father was ailing, and it was up to her to “work the farm, milk the cows, and spend a lonely life by the sea,” as Robert Mooney explains in

Nantucket Only Yesterday.

She was a strange woman, big, ugly, tough, and private. What probably saved her sanity was her connection to the Coast Guard boys at the small Madaket Coast Guard station. “The lonely young sailors took a liking to her, and she ran errands to town for them.” World War II provided some excitement. “Millie was the civil defense officer and air raid warden for Madaket, which she patrolled on a big horse. Woe to the careless customer who violated the blackout on Millie's watch.”

After the war the station closed, but Millie was given a plaque for her cottage designating it as the United States Coast Guard West End Command, and was officially appointed Chief Officer. She wore the Coast Guard cap over her wild hair for the rest of her life. She was no simpleton, and bought up a fishing shack or two near Hither Creek, renting them out to young people. In fact Maggie, a twenty-three-year old girl from Boston, whom I was eventually to marry, lived in one of Millie's properties. Maggie never saw Millie except to hand over the rent, and although she doesn't like to admit it, the woman scared her. For that matter she scared me.

Madaket Millie.

But the town was proud of her, and protected her. The oral history describes the death of her father, who had been bedridden for years, cared for, cleaned, and fed by Millie alone. When the body was delivered to the hospital it was clear that the old man had been shot in the head. Quite a few nurses and hospital workers must have noticed it, but the doctor on duty was also the medical examiner for the County of Nantucket. He filled out the form, listing the cause of death as heart failure, and signed with a flourish. A brave act, if indeed it happened. The doctor was rather an odd fish himself, with only a partial belief in the science of medicine. He was very cavalier with his patients, including me, one of his friends. I never asked him about the story because I knew I'd never get a straight answer from him, so much did he love affecting an air of mystery.

TAKE ANOTHER LOOK at the map. I lived about halfway between the towns of Nantucket and 'Sconset, off Polpis Road behind the first salt marsh at the south end of the harbor. In those days there were no other houses nearby. I saw a completely different Nantucket when I became a year-rounder, a pretty tight place where it wasn't easy to make a buck. The action in townâthe rebuilding of the harbor and other Sherburne projectsâwas covered by old time local labor. I managed to survive the first winter by doing magazine work by mail, playing the piano in a year-round bar, cashing small royalty checks from my book, and living on the cheap. I installed electric heaters in the bedroom and the kitchen, but the barn hadn't been built with winter in mind and I spent a lot of time in the crawl space underneath working on frozen pipes with a propane torch, or installing new ones with an instruction book lying open in the dirt in front of me. My mortgage was $600. I discovered anew how claustrophobic and narrowing it is to live with little money. (I'd known it in my childhood, too, although in a different way.) The amount of time and energy spent on small household and automotive tragedies. The frustration of not being able to go anywhere more than ten miles away. The fact that even with long winter underwear it was cold. The brutality of the wind in February, humming through the thin spaces in the barn's oak siding.

I tried scallop fishing, but I wasn't strong enough and it was dangerous work. I kept warm many nights, and kept myself in beer, by shooting darts in a pub, as I'd done at college. I spent the first winter like quite a few of the locals, simply waiting for summer.

“Don't sink,” my lawyer had said on a brief visit to check up on me after the divorce. “Some guys just sink. Don't.” He wasn't talking about boats.