Time & Tide (7 page)

So Much to Do

FAMILIES THINKING OF RENTING A HOUSE for the summer should be aware that Nantucket is nothing less than a paradise for children. My three sons (now age forty, thirty-eight, and sixteen) all had unconscionable amounts of funâand this is one area where the island is even better now than it was when my oldest were kids.

Let's start with small kids. What does one do with them? All of my kids picked blackberries along the sides of the long driveway leading to our house. (How do you make a driveway? You simply drive over the same track, time after time, and you wind up with a dirt road, with grass in the raised center strip. Over the years the road sinks down, and you get puddles when it rains.) For all of my kids, and for Jonathan and Nicholas, my three-year-old twin grandchildren, picking berries was the first foray into the outside world of the island.

Everyone's first beach experience was on the shore of Quidnet Pond, where only thirty yards of dunes separate the waters of the open harbor from the intimate pond, always calm whatever the weather. Quidnet is a cluster of housesâmost of them modest old-money summer homesâfar enough away from everything to be a sort of secret, special place. Small children play in the sand, wade in the water, and make up games. Sometimes a mom throws a tennis ball for her pooch (quite often a Labrador) to retrieve. Sometimes a dad will fly a kite, or shmooze with other dads, all the while keeping an eye on the water. The kids are totally absorbed with one another, and it's rare to see them fuss.

What youngster could pass up throwing bread into the pond off Polpis Road near Hollywood Farm (no longer a farmâalthough once what is called an old lady's farm where my first wife and I would buy baby vegetables and really splendid watermelon pickles made by Mrs. Maglathlin, the owner) in order to see the snapping turtles rise to the surface?

And what about hermit crabs at the Brant Point breakwater? The sight of these prehistoric life forms seems specially thrilling to the young. As the kids grow a bit older they might go out to Madaket Bridge and throw chicken legs, tied with a long string, into the water to catch crabs. Again the fascination of primitive life forms, spiced by the aura of danger. Watch those claws!

The kids discover the joys of clamming and of the fact that you can bring something back for dinner even if you're only seven years old, let's say. We always went out to a tidal flat near the entrance to Polpis Harbor in our boat, with the dog. Maggie and I might swim while Tim, my youngest, went off with a bucket for an hour. We could see him in the distance, hunkered down, his small form bright in the stark sunlight, elbows akimbo, digging with purpose. Or on a foggy day, he would simply disappear as the sound of buoy bells rang muffled in the air. We call it Tim's Point, and we go there often.

There are any number of children's groups, from the Wee Whalers, a day-care operation, to the more upscale Maria Mitchell Association's nature group with visits to interesting sites around the islandâ places like Gibbs Pond, hidden away in the moors, or various marshlands. A group called Strong Wings provides a kind of outward-bound experience, encouraging kids to test physical and mental limits. (Many children's groupsâmore than oneâvisit a conservation holding in the forest next to our house. We can hear their voices from our vantage point on the rear deck, and they sometimes cross over into our little forest, or so it sounds.) Dozens of play groups feature different kinds of activities. Even the Nantucket Island School of Design and the Arts, NISDA, has programs for children.

When it rains there is a splendid children's wing in the Atheneum, in the town library, with readings, singing, and various games. The hall above the main library was the site for many famous lectures in the nineteenth century. The lectures and readings for adults continue on, but the library has recently shown a gradual but definite tilt toward childrenâwho sometimes spill out into the adjacent park to roll in the grass or climb the trees.

The recent introduction of public transport, buses on a regular schedule, has opened things up for older children, who can go into town whenever they want to eat pizza, get ice cream on old South Wharf, or pick up a video to take back home. Parents need not worry because the island is safe. Kids can go anywhere, and they do, enjoying a kind of independence no longer possible on the mainland.

Boat rides around the harbor are always fun, and somebody's dad seems always to suggest a trip out to Tuckernuck, where on the way one sees seals basking in the sun on Esther Island, black eyes flashing above their whiskers. The south shore of Tuckernuck is a splendid place to fish for striped bass and bluefish. The island used to be half deserted, and I can remember coming over in Walter Barrett's boat as he delivered mail and groceries to the tiny pier. As soon as one stepped on land a hundred seagulls would begin to track from the air, gradually coming closer, diving down like creatures in a Hitchcock film. A bit scary, always, as I walked across the sandy ground to the old LaFarge compound, where I had friends. (In fact my first wife contracted hepatitis there, eating shellfish from the inlet.) Nowadays there are quite a few houses and the land is expensive, if any is available. The fishing is still superb, either from the shore into the surf, or from a boat outside, casting back into the surf (Ã la the late Bob “Stinky” Francis, a local who took out fishing parties for a feeâor for no charge if you got skunked).

There is the Dreamland Theater, where the audience is less inhibited than at any other movie theater I know. The big summer movies are always packed with kids laughing, hissing, and booing like Italian opera fans. I saw

Psycho

at the Dreamland when it was first released, and will never forget the shocked, almost dazed look on people's faces as we emerged, many of us going directly to Gwen Gaillard's Opera House for a stiff drink.

There is also the tiny Gaslight Theater, but for kids the best movie venue is probably the old hall in 'Sconset, where the audience sits on folding chairs and everybody knows everybody else. A true summertime feeling, not much different than it was thirty or forty years ago. As I mentioned before, 'Sconset has worked hard to maintain its traditions.

Teenagers do not need cars (although many of them seem to have the use of them) because they can bike anywhere on the extensive network of bike paths or take the bus. They go to the South Shore with Boogie boards or surfboards, having called the hot line for an up-to-the-minute description of the size of the waves. They can spend a long timeâall dayâat Cisco or Nobadeer beaches knowing they can get hot dogs and ice cream from the truck or from the hip vendor who uses an old motorcycle with a dry-ice sidecar.

Beach parties seem to occur quite often in the evenings, and teenagers get to know each other, sometimes very well indeed, and perhaps quaff an illicit beer or two before the recently imposed ten-thirty party curfew. The cops, who show up on dune buggies, are invariably polite and understanding, some of them not much older than the kids. They are able to blend in, sort of, standing around the bonfires with everybody else.

All sorts of activities are available. At sixteen, Tim rides horseback with his pal Seth in the shallows of Polpis Harbor or on Quaise Pastures. He plays tennis in 'Sconset (and works at the club desk scheduling games for people), jogs to Altar Rock, practices stick-shifting on isolated dirt roads, or goes into town for a pizza on our old fifty-horsepower duck boat. The day is not long enough for him and his buddies. They love the island with a passion and never seem to take it for granted.

Boats

AS WE HAD THIRD WORLD SOFTBALL, WE ALSO had the more amorphous Third World Yacht Club. The first members being myself and John Krebs, a pal who keeps his inflatable on my point since he does not have access to the water from his property. I started with an old scallop boat, and actually tried to earn some money scalloping with my friend Phil.

We worked the harbor, and work it surely was. Winter. Socks, and then wool socks for a second layer. Rubber boots that almost reached your knees. Long underwear, jeans and wool shirts, a heavy sweater and full weather slicks. Workman's gloves. We would putt-putt through Polpis Harbor out into Nantucket Harbor proper, cutting the engine when we reached a likely spot, which meant a smooth rock-free bottom where scallops rest in the eel grass. Chain-link dredges on iron frames are tossed overboard, the engine is started, and the ropes begin to feed out. When the dredges fall into the proper staggered pattern, a bit more power is coaxed from the outboard engine and the dredges are pulled twenty-five yards or more. The outboard is placed in neutral, and the outboard “donkey engine” (scavenged from a lawn mower) is cranked up, its drum extension turning, waiting for the rope which gets wrapped around the drum in such a way that the dredges, one by one, are pulled in.

There is a culling board athwart the center of the boat. The most dangerous part of the operation is leaning over the side and manhandling the dredge, now full, weighing close to a hundred pounds, up onto the culling board to spill out crabs, seaweed, eel grass, gunk, and, one hopes, scallops. It is at the precise moment of pulling up the dredge that you can slip and fall overboard. With the boots, heavy clothing, and slickers, drowning is a certainty without quick help from one's partner.

The scallops are picked out of the mess on the culling board, the year-old ones (you can tell by the rings) thrown back into the water along with the slightly slimy vegetation. Then the dredges are thrown over and another run commences.

I gave it up one foggy day when I was out alone. I was getting scallops, but at one point I almost lost my balance. I was simply not strong enough to pull up the dredges smoothly, and I had a sudden flash of my vulnerability. I decided then and there to give up scalloping, and in fact never attempted it again. (Phil was also ready to throw in the towel.) Instead I used the boat to go fishing when the weather was warm and the sun shone.

During the summer I worked at night, playing jazz, or now and then doing magazine pieces in the daytime. I found myself spending more and more time fishing, not for money, but because I liked it.

Island wisdom had it that Polpis Harbor held so few fish that working it would be a waste of time. I was absurdly pleased with myself to prove otherwise. I fished with a surf rod, standing on the culling board, and I discovered that Polaroid sunglasses allowed me to see into the water to a depth of four or five feet. Weeks of moving from spot to spot, throwing anchor and casting the shiny drail, allowed me over time to discover that striped bass, and the occasional bluefish, entered and exited the harbor along specific channels, and that even at the southern end they moved along certain pathways. I could see themâdark, fast-moving shadows streaking along over the sandy bottomâand I learned how to cast in front of them. The excitement attendant to a strike, the sudden pull, the fish often leaping up into the air, never failed to thrill me, no matter how many fish I caught.

The sought-after fish is the striped bassâmild, sweet, and easy to cook. Bluefish, much more common in Nantucket waters, are oily, with a strong fishy flavor, and make a fine pâté (an island specialty). They can be broiled, soaked in gin, and touched with a lit match to lift out some of the oil, as the late Robert Benchley used to do it, to good effect.

There is a curious fact associated with bluefish. Wauwinet, Quaise, Shawkemo, Polpis, Quidnet, Madaket, Coatue, etc., are all Anglicized Indian names. Indians were the first people on the island, as far back as circa 300 A.D., the carbon date for some deer bone tools dug out of the earth.

Stone arrowheads and blades can be found all over the island by the trained eye. (The Unitarian minister has more than once plucked up an arrowhead from my driveway, despite my having searched carefully and finding nothing. He has a wonderful collection.) The Indians died out, and when the last one expired, the bluefish disappeared. The oral history connects the two events. For seventy-five years not a single bluefish was caught. These days it is not uncommon to see small boats come in with big catches, the fish having returned even if the Indians did not.

A small cycle occurred in Polpis Harbor, where twenty-five years ago there were so many blue shell crabs scuttling around that I could pole net twenty or thirty in an hour. They disappeared for quite some time, but show signs of coming back.

I remember one morning in the early seventies when I was anchored in a particularly good position on the south side of Second Point, where the channel the fish used was narrow and well defined. My reel was snarled and I sat down and fixed it. When I looked up I saw two friends, who'd heard that I was catching fish, in a rowboat fishing on the other side of the point. We waved to each other and I thought of telling them to come over, but some atavistic fisher/ hunter reflex kept me silent. It was (at that time)

my

harbor, after all. So Alan and Twig had to sit in their boat, catching nothing, and watch me pull in three nice-sized bass in perhaps twenty casts. Later, I told them during a beery dart game about the channels, but they never came back. It was a long haul from town, in any case.

I really didn't have enough money to maintain

Que

Blahmo

properly, but I was determined to keep it. Mooring was a problem, since I did not have a mushroom (as they called it). I tied cement blocks (no good) and finally a heavy iron engine stand, which seemed to work. In the morning I could look out my window while eating breakfast and see the heavy, green, funky boat bobbing in the water.

Eventually there was a gale, from the south, and the boat pulled the engine stand out of the mud and dragged it up harbor, where

Que Blahmo

finally sank, fifty-horse Evinrude and all. Here one moment, totally gone the next.

I should have gotten the message and washed my hands of the whole business, but I didn't. With the kind of stubbornness that can affect you when you're close to broke, I insisted on keeping up my fishing life-style, not falling back, as it were. I began to haunt the shipyard out in Madaket, finally acting when an inexpensive used boat became available. I got it cheap because it was aluminum, and riveted hulls were definitely out of favor on Nantucket. It was an old black Starcraft from the fifties, with red vinyl seats, a padded dash, and a windshieldâso retro I had to have it. No more standing on the culling board, but I already knew where the channels were, so it didn't matter. I called it

Elvis,

and it was fast enough so I could take my boys water skiing, which they loved for a couple of years and then mysteriously lost interest. I had gotten a mushroom this time, but stupidly overlooked the proper clasps, knots, and other paraphernalia with which the rope from the boat is attached to the mooring. Simple ignorance. One afternoon, during a hurricane, I stood at the rain-streaked window thinking I should have beached the boat, only to see a granny knot fail and the boat sail away up harbor with the wind.

I ran down to the water, and then along the shore as the boat lurched along in the angry water to come to rest in the shallows of the long spit of land separating the north end of Polpis Harbor from Nantucket Harbor proper. The wind was fearsomeâseventy to eighty miles an hour, I would later learnâbut as I saw waves breaking over the stern of the boat I jumped into the waist-high water and got behind it, hoping to save the engine. As I struggled (ineffectively) to lift the stern, a sudden gust took the glasses off my head. In a surreal moment I watched them fly up into the air, way up, and disappear over the spit, higher and higher, smaller and smaller, until I couldn't see them anymore. The boat swamped and the engine was lost. Eventually the wind actually blew the boat over and upside-down, bending the windshield beyond repair.

Elvis

was trashed out, and, brokenhearted, I would eventually give the hull away.

Boats are more heartbreak and worry than they are a joy. Something always seems to go wrong. An engine briefly catches on fire on the way to Coatue. The battery dies for no apparent reason. The draining hole stopper dries out and springs a leak. I don't know how many mornings I would come down to the window half expecting the boat to have disappeared, then relieved that it had not, but still nervous enough to worry if the stern might not be riding a bit heavy in the water. I knew I wasn't the only one to feel anxiety. My good friend David Halberstam had a Boston Whaler for a while, from which we fished out in the ocean, but he finally gave it up. “Marine engines,” he said. “The tolerances are like airplane engines, so they're expensive, but they keep conking out anyway.” For many years now he has glided through the harbor in his racing scull, keeping fit while enjoying the water.

Gracie and Maggie.

The fact is, once you've tooled around in Nantucket waters, once you see the island from that vantage point, you can't easily give it up entirely. It becomes essential that you have a way to go over to Coatue for private skinny-dipping, or into town via the harbor to see the hundreds of yachts moored there or tied up at the docks. In recent years there seem to be more and more really big yachts, sometimes with helicopters tied down on deck. Frank Sinatra sailed in one day, a young woman dressed in white playing a flute in the bow as they docked. The boat was enormous, of course.

And there are more intimate pleasuresâbird watching from a kayak small enough to let you navigate up a stream, and then back down to, for instance, Polpis Harbor, where Maggie likes to paddle along with our dog Gracie shadowing her.

THE YEARS PASSED, during which I began teaching at the University of Iowa and M.I.T. My financial situation improved markedly, and I started haunting Madaket Marine again. And so I came by the boat we have today, a seventeen-foot Chincoteegue brought up from the Chesapeake (it's a duck boat) by a member of the Dupont family who fell too ill to use it. We named it

Buzz Cut,

and we're now on the second engine.

During the season a lot of people live on their boats, and the harbor fills up. The launch is in continuous operation taking people to and from the wharf. I should mention the Nantucket Lightship (a floating lighthouse), which was decommissioned years ago, spent time in various mainland harbors, and was finally brought back to Nantucket by someone who bought it on eBay. Fitted out for landlubbers, it can be rented, and lived in, for fourteen thousand dollars a week.

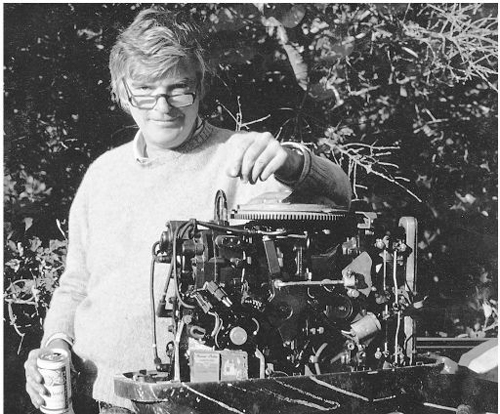

Frank and engine.