Karma for Beginners

Copyright © 2009 by Jessica Blank

All rights reserved. Published by Disney ⢠Hyperion Books, an imprint of Disney Book Group. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. For information address Disney ⢠Hyperion Books, 114 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10011-5690.

First Edition

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

This book is set in 14-point Perpetua.

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data on file.

ISBN 978-1-4231-4347-5

Reinforced binding

For Mom, Dad, and Natasha

NE

. . .

To open up your consciousness, you must detach yourself completely from the life you thought you knew.

I had to fight for this hamburger. Twenty minutes: in the rest stop parking lot and the bathroom, by the pay phone while my mom called work to make sure they had the forwarding address for her last paycheck, and then the entire time in line, past the fried chicken and the biscuits and the french fries and the milk. My mom didn't give in till we were at the register, when she finally said, “Fine,” held her hands up to heaven and closed her eyes, apologizing to the endless wheel of karma, while I ran back and grabbed the hot crinkly foil-wrapped cheeseburger and brought it to the cashier, in front of whose astonished face my mom was still praying.

I was born a vegetarian. Really: my mother, Sarah, spent her pregnancy, which straddled 1971 and 1972, on a diet composed exclusively of brown rice, adzuki beans, and overcooked broccoli. When I was born I got the same stuff, just pureed. I was eight years old before I tasted meat: one day when my mom left me at my friend Hillary's, I was taken on a forbidden trip to McDonald's and bought a forbidden Happy Meal with a forbidden hamburger inside. My favorite part was the little rectangles of onion, sweet and soft, the bite flash-frozen out of them. My least favorite part was the hour I spent throwing up afterward because my digestive system had never encountered meat. And my

least

least favorite part was explaining to my mom, when she finally showed up, why I got sick. My mom said the throw up was karma, and when I got to the dry heaves I should imagine how the cow felt.

This time, though, when I unwrap the burger my mom doesn't say anything. She just sits there steaming while I go to the Fixin's Bar for ketchup and mustard and perfect bright green pickles made much more delicious by the artificial color, and when I get back to the orange plastic table and eat the whole thing, she shoots me a look made out of daggers. She can't stand losing.

She gets an A for effort, though; she used all her tricks in line. First the warning: “Remember what happened last time you ate meat?” Next the guilt trip: “You're already fourteen years old. Don't you think it's time to develop some compassion?” Then the lesson: “You're eating all that poor cow's pain, you know. It stores up as toxins in your blood. Plus you'll have to do a lot to balance out that karma.”

But I didn't fold. Instead, I used my trump card. I waited till we were in earshot of the register, and then I said: “You're taking me out of my school and away from my friends and off to live in the cold woods with a bunch of people who worship some weird guy in orange robes. The least you can do is let me

eat

.”

I got the burger.

It was sort of a lie, I know. I don't have any friends to be taken away from. And it's not

so

weird, the place we're going; it's an ashram, not unlike the New Age centers she's been going to on weekend trips for workshops since I was five. But this time we're going to

live

there: no house, no school, no backyard or apartment or car. No drive home at the end of the weekend intensive; no slipping back into the crowd of my classroom where nobody asks my deep inner dreams and I can just sit at my desk and listen to other kids talk about TV shows and laugh like I know what they're talking about. None of that; just a room, stacked up on all the other rooms, and a name tag, and a four a.m. wake-up for chanting. Forever. I wanted a hamburger.

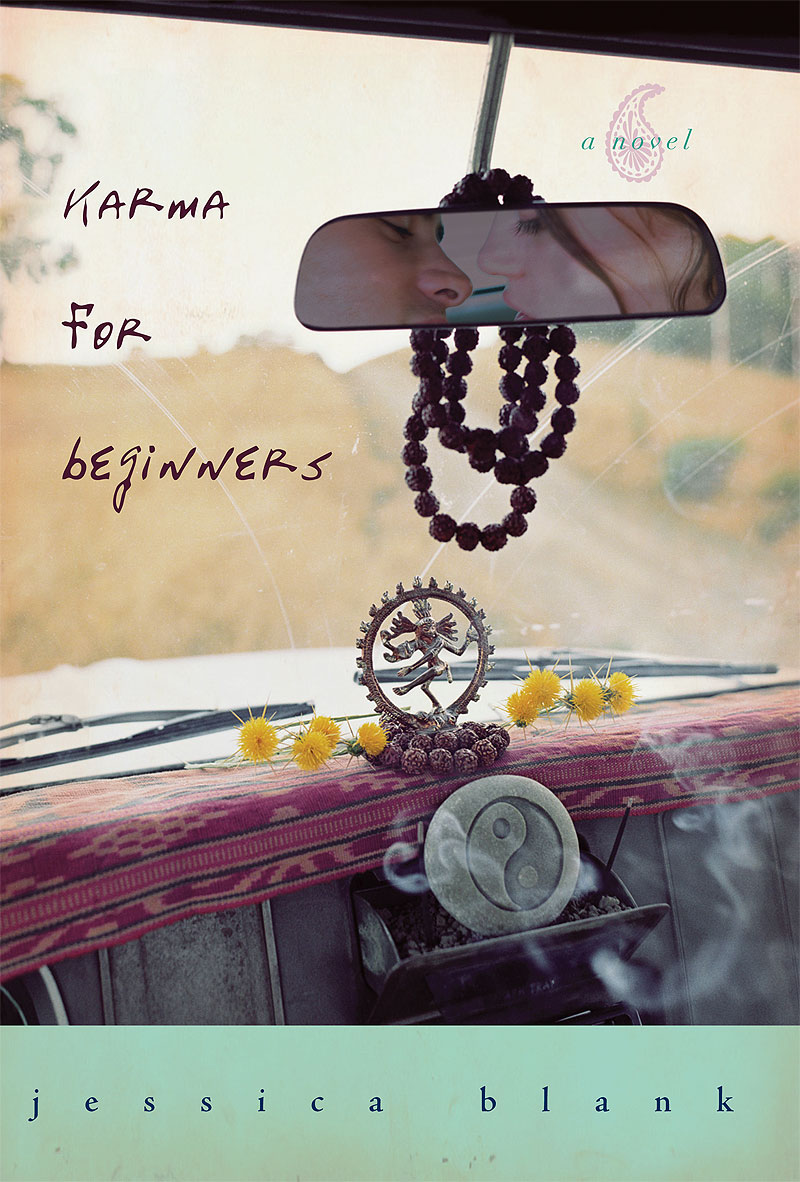

I climb back into the passenger seat, the revenge burger rumbling in my stomach, and strap the seat belt tight across my chest. She leaves hers undone.

“I've decided to forgive you for that little act back there, Tessa,” she tells me. “I understand transitions can be stressful.”

“Great. Thanks,” I say.

“I know it must be tough to leave right when you're starting high school. Did you feel special about your new school?”

I look at her like:

special?

“No, Mom, I didn't feel âspecial' about it. I don't care.”

She squints like she doesn't quite believe me, which just makes me madder, and then she turns her key in the ignition. We pull onto the highway, dart between trucks and slide into the fast lane. I grip the sides of my seat, brace my feet against the dusty dashboard, but no matter how tight I wedge myself in we still keep moving.

That's sort of how it always goes. As soon as I get to know the trees and the kids and the walk to school, it's time to follow some guy or get away from one: skip out on last month's rent, pack our stuff in boxes, and strap the futon on the car. So I don't really think of any of my schools as “special.” Mostly I don't think of them as anything, except another place I'm gonna leave. The buses are always the sameâripped upholstered seats and the popular kids in the back, too-loud laughter circling them like an electric fence, and when the bus stops you just spill out into another set of Lysoled halls and sparkly clean linoleum and fake wooden-plastic desks. I've been wearing weird secondhand clothes since kindergarten. I just read my books and the teachers think I'm smart and the kids think that I'm stupid and everyone lets me alone until it's time to leave again.

My life so far we've lived in Akron, Dayton, Youngstown, Venice Beach, then Akron again, plus one summer in Big Sur where my mom cleaned guest rooms at a Retreat Center in exchange for a tent in the redwoods and use of the outdoor hot tubs between three and five a.m. So we're portable. My mom says it's important to be portable, and then she'll talk about the sixties when everyone was On the Road except her because she was still fifteen and locked up in my grandparents' yellow split-level.

This trip she'd gotten up to 1969 when she ran out of banana chipâsunflower seed mix and I whined that I was hungry and we had to stop at Roy Rogers for lunch. I was hoping she'd forget about the beginning of the seventies by the time we got back in the car.

No such luck. “Tess, I wish you could have seen it. Everyone was

together

in this amazing explosion of, just, honesty, and joy, and excitement about

life

â”

“Right, and having be-ins and dancing all night and traveling around.” I'm hoping that she'll notice that I already know what's coming next.

She doesn't. “It was incredible. You would find people you

connected

with and just live like gypsies, on the road, exploring what it meant to be alive together when all the rules disintegrated and you were finally really, truly free. As free as a tree is, or a flower, or the wind. Free like human beings are

supposed

to be.”

But instead, her first year of community college she slept with this older guy with a ponytail named Jeff who came into town playing bass in a rock band and then he took off on tour and then she had me. So no freedom-flower band of gypsies.

“Oh, Tess, I wanted to be part of it so bad. I wanted to find my tribe. I was just about to get out thereâ” And then suddenly she goes quiet, and gets that look like she's thinking something she doesn't want to say. “But. You know.” And I do.

“But that's okay, Tess. We can make our

own

freedom. We really can. If we just quit searching for security and safety and all those stupid things that are just illusions anyway, then we can do it right now. Right here.” She waits for me to say something, but I don't. “Right?”

And then she stops looking at the road and turns to me with shiny eyes, full of hope and trying to make it true, and I know I have to tell her, “Yes, we can.”

She says we're here to make our freedom, but secretly I think we're here because of guys. We do a lot of things because of guys. Ever since my dad left for good when I was four, they've been parading in and out, and every one's eventually a Disappointment. There are the ones who wear a suit and take my mother to the Olive Garden and talk about their ex-wives all night, and the ones who tell dumb jokes to make me think they're cool and then sort of hit on me. The guys she meets in crystal healing workshops are all ugly and have stringy hair. Sometimes she finds a man who Follows His Bliss like her, which also means he Doesn't Know How to Commit. But her biggest weakness is the hunky guys who work at the lumberyard and think that she's Exotic. She'll toss her long brown hair at them and lean her hips forward and forget that in three weeks Exotic will start to mean Weird and she'll come to me crying, saying that no man will ever understand her and she might as well just give up.

The last time that happened, two months ago, she made us mugs of Lemon Zinger, pulled me onto the futon in her room, and said, “Tessa, let me tell you about men.” Her eyes were red.

I picked at the tan and burgundy swirls of her Indian tapestry bedspread. I didn't want to talk to her when she was crying. “Mom, can't I just do my homework?”

But she was firm. “You're fourteen; it's time for you to know.”

“Please, Mom, it's weird.” I could feel her eyes on me. I stared hard at the futon. “I'm only in ninth grade.”

She shook her head. “Tess, you're a full being with your own consciousness. I don't buy into this whole âshelter children from reality' thing. You're a person. And you need to know how it works.”

And then she made me look at her and told me about how you can't ever count on men, how they never really value who you are inside, how they pretend to care because you're beautiful and then they lie and leave. Her voice choked up while she was telling me. I wished I could crawl under the blanket. Then she took my hand.

“But here's the good thing, Tessa. I've learned that all that bullshit drama isn't even necessary. Screw them. I've sworn off men. I'm focusing my attention inward.” She held on to both my hands. “It's a whole new phase. You'll see.”

That week, she switched from Tao of Relationships class to meditation group. Then she started waking up at five a.m. to say a Hindu prayer that lasted an hour. Then she quit her job.

So now we're on the way to this “ashram” place, her scarves and books and pottery piled into cardboard boxes, Rolling Stones in the tape player, and she's still talking about guys.

“You know, though, Tessa, I really should be thankful. I mean, Rick and Dan and all of them were disappointments, but at least they didn't abandon us like your dad.”

I look out the window at the gas-food-lodging signs and pretend I'm not really listening, that I don't care about the things she's going to say. But my palms sweat and my fingernails dig little moons in them and I think:

Please

. Please tell me something that I've never heard before. Please tell me about my dad.

Here are the things I know: 1) His name is Jeff. 2) He is a bass player. 3) In 1971, he was in a band called Strawberry Express that toured Midwestern colleges, several of which were in Ohio, one of which was my mom's. 4) He stayed for four days. 5) He is currently in a band called The Green Tea Experience, which has recorded one album on a small record label called Honest Groove Records. 6) None of the letters I've written to his label have ever been answered.

I also know several other things about my dad, courtesy of my mom, but I'm not sure that I believe them. For example, he is an asshole. He's let her down too many times to count. The last time he came back, when I was four, they had a fight and her attempts to

just communicate

were thwarted so profoundly that she finally had to “approach him physically” so as to “wake him up” and then he shoved her. Hard. And this is unforgivable, so she's been telling me since I was eight and “old enough to know,” and he is dead to us, and betrayed our family karma so profoundly that it cannot ever be resolved. That's what she tells me.

I wish that she would tell me other things: what he sounds like, where he lives, what it feels like when he looks at you. Every time I wait for her to do it, and every time she never does. But then I realizeâshe said we're going to the kind of place we've never gone before. A place that will finally be different. Maybe this could be the time I'll finally ask her and she'll finally answer.

My heart is beating really fast, which is kind of weird. I'm just sitting here.

“Mom?” It comes out kind of squeaky. “Can I ask you a question?”

She doesn't answer. I'm not sure she even heard me. So I try again: “What did Dad look like when you first met him at that concert at your school?” I repeat it to myself:

Please

. Please just tell me the story. Give me a picture I can carry in my head.

But her voice just toughens. “You know, Tessa, people like him, you can't want anything from them. Because you'll never get it.”

I stare hard out the window, squint at the open space, grass and skinny trees and no one talking. I taste iron in my mouth and I realize I just bit my lip. And then I feel:My cheeks are hot. And wet. I'm crying. Shit. I try to hide it, but she hears me sniffle.

“Tess.” She takes her eyes off the road and looks at me. “Tess, what's wrong?” Her voice goes soft and she suddenly sounds like a mom. But in the good way.

“Nothing.” I want to wipe my cheeks, but it feels embarrassing.

“Honey, c'mon. Something's wrong. Just tell me.”

It feels good that she wants to know, but I wish she would've guessed. Because I can't tell her. I can't explain to her how all these parts of me need her to shut up about my dad, but just as many need her to keep talking. I don't know how to say that.

“Oh, Tess. I'm sorry,” she says. My teeth stop clenching and I almost cry again from the feeling of

thank you

. Oh my god, she's finally going to realize I need her to stop hating him. She's saying sorry.

“I totally apologize. We're right at the start of an adventure and I'm being such a downer,” she goes on. “You're totally right.”