This New Noise

Authors: Charlotte Higgins

THE EXTRAORDINARY BIRTH AND

TROUBLED LIFE OF THE BBC

Charlotte Higgins

In memoriam

Georgina Henry

1960–2014

‘Wireless’, a term that has far too recently entered our vocabulary, a term whose success has been far too swift for it not to have carried with it a good many of our era’s dreams and for it not to have provided me with one of those rare and specifically modern measures of our mind. It is faint gauges of this sort that occasionally give me the illusion that I am embarked on some great adventure, that I somewhat resemble a seeker of gold: the gold I seek is in the air.

André Breton,

Introduction to the Discourse on

the Paucity of Reality

(1924), translated by Richard Sieburth and Jennifer Gordon

The BBC came to pass silently, invisibly; like a coral reef, cells busily multiplying, until it was a vast structure, a conglomeration of studios, offices, cool passages along which many passed to and fro; a society, with its king and lords and commoners, its laws and dossiers and revenue and easily suppressed insurrection …

Malcolm Muggeridge,

The Thirties

(1940)

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Introduction

- PART I:

ORIGINS AND ARCHITECTS - 1

Reith of the BBC - 2

‘People, telephones, alarms, excursions’: Hilda Matheson - 3

Inform, Educate, Entertain - 4

‘Television is a bomb about to burst’: Grace Wyndham Goldie - PART II:

SLINGS AND ARROWS - 5

The Great, the Good and the Damned - 6

‘A spot of bother’ - 7

Independent and Impartial? - 8

Enemies at the Gate - PART III:

UNCHARTED SEAS - 9

‘The great globe itself’ - 10

‘The monoliths will shake’ - 11

Conclusion: Welcome to the BBC

- A Note on Sources

- Select Bibliography

- Acknowledgements

- Illustrations

- Index

- About the Author

- Also by Charlotte Higgins

- Copyright

The BBC is an institution at the heart of Britain. The BBC defines and expresses Britishness – to those who live in the UK, and to the rest of the world. The BBC, to my mind at least, is the most powerful British institution of them all, for, as well as informing, educating and entertaining, it permeates and reflects our existences, infiltrates our imaginations, forms us in myriad ways. It seeps into us. It is the stuff of our inner lives.

Unlike, say, the monarchy, or the armed forces, the BBC is an institution that is still young. As I write there are still those alive who can remember a time before the wireless. And yet in so many ways the age that birthed the BBC – that of modernism and the rise of mechanisation – can seem completely out of reach, as alien to us now as the ancient world. The years that separate us from its formation have been years of rapid change: the mass production of antibiotics, the Second World War, the atom bomb, the contraceptive pill, the Internet, 9/11, the rise of China … Perhaps, though, the threshold on which we stand now, hovering irresolute as we do between the analogue and digital eras, is not so different from the frightening and exciting changes wrought by modernism. The body politic, then as now, had a series of important choices to make about how to incorporate

epoch-defining technological advances into the lives of the citizenry.

This book comes out of an unusual journalistic assignment. Alan Rusbridger, the editor of the

Guardian

, asked me to suspend my normal work as chief arts writer, and spend ‘several months’ researching the BBC. The fruits of this enterprise would be a series of long essays for the paper, and this book. The notion was to try to deepen the debate about the broadcaster, which had often been shrill and bad tempered. Alan asked me to try to get under the skin of the institution. Cheerfully, he informed me it was the biggest single assignment he had ever commissioned.

‘Several months’ turned into a year. The scale of the organisation alone (at the time it had 21,000 employees) and the range of its work made the task immense. Trying to understand the BBC is like trying to understand a city-state. It has its court, its grandees and aristocrats, its artists and creators, its put-upon working class, its cliques and dissidents and rebels, its hangers-on and corrupters and criminals. It has its folklore and mythology, its customs and rituals.

Over my year with the BBC, I spent (or so it seemed) more time in the BBC’s various offices than in the

Guardian

’s. I conducted over a hundred long interviews with employees and those who knew the corporation well, from secretaries to directors general. I became convinced that to understand the BBC it was necessary to delve into its past, and so I absorbed as much as I could of the huge literature on the BBC, starting with Asa Briggs’s

multivolume history of British broadcasting. Towards the end of the project, I also spent time in the BBC’s Written Archives. It became clear to me that many of the qualities of the BBC are still dependent on the way it was first shaped. As one BBC journalist said to me, ‘Reith still stalks the corridors.’ Concomitantly, many of its recent problems have been foreshadowed and prefigured. The aim was not to present a linear history of the BBC but to offer a picture of the corporation as I encountered it over that year, deepened and enriched by the soundings I would take in the deep waters of its past.

In October 2013, when I began the assignment, the BBC felt fragile and insecure after the travails of the recent past. Less than a year earlier, George Entwistle, the director general, had resigned after only 54 days in post, as a result of two closely connected scandals. These were the handling by the current affairs programme

Newsnight

of allegations into sexual abuse by the BBC’s one-time star, Jimmy Savile; and the incorrect naming on the Internet, after an investigation by the same programme, of an innocent man as a paedophile. The BBC Trust’s chairman, Lord Patten, had also come under enormous pressure, and would resign through ill-health partway through my work on the BBC, in spring 2014. The BBC’s huge pay-offs to former managers were also under public scrutiny, and the corporation was being severely criticised for an abandoned technology project, the Digital Media Initiative, which had cost £100 million. No day passed, it seemed, without hostile headlines, the enmity of elements of the press fuelled by commercial rivalry.

There was perhaps even a greater existential threat. The BBC now operates in an era of unprecedented media fragmentation. We live in a world of Netflix and YouTube, of Google, Amazon and Apple – a world in which anyone can be a broadcaster, a world where the sheer bulk of encroaching global media businesses threatens the corporation. In my childhood the BBC was grandly dominant, standing out on the horizon like a great cathedral on a plain; only ITV and, later, Channel 4 were also visible in the landscape. Now that plain was built over and populous; great edifices loomed above the BBC, and threatened to cast it wholly into shadow. The very funding mechanism of the licence fee – a levy on television ownership – was beginning to look outmoded and shaky in the world of catch-up, the tablet and the smartphone. Politicians, for the most part, seemed indifferent or hostile, especially on the right. Urgent questions presented themselves: were we, as a nation, drifting towards squandering the inheritance of the BBC through sheer carelessness? Was the BBC worth fighting for? Had it grown too unwieldy and too powerful, as its detractors claimed? With its vast and tentacular commercial operations, was it trampling its smaller rivals? Was it succeeding in its basic and founding aims of impartiality and independence? It was with such questions in mind that I entered the great citadel of the BBC.

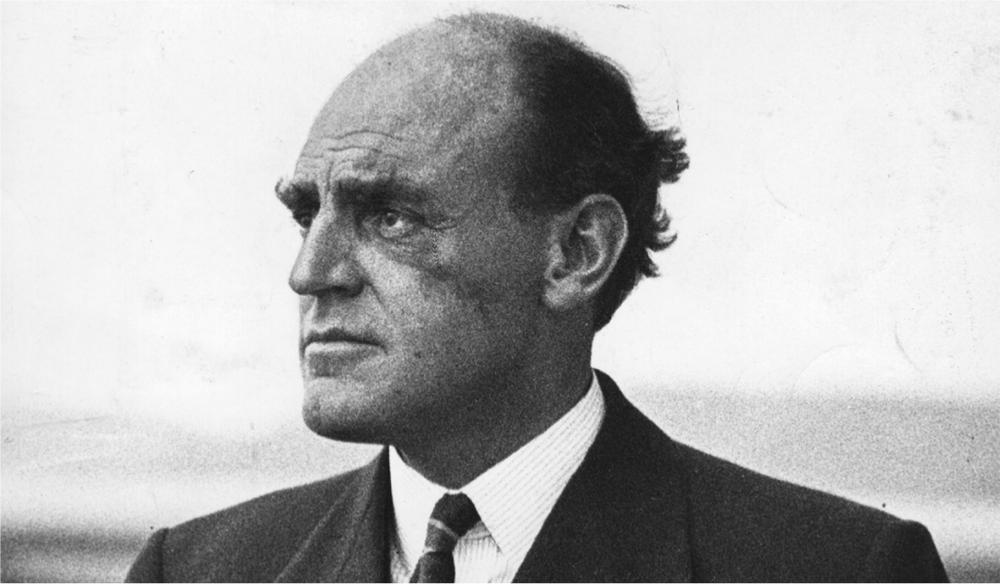

The manse on Lynedoch Street, Glasgow, is a handsome double-fronted house with nine steps up to its front door. It clings to the flank of its sandstone church, whose brace of tall, pencil-straight towers are linked by an elegant classical pediment. The manse – which still exhales an air of four-square Victorian respectability – occupies the high ground above the wide green spaces of Kelvingrove Park, in which, before the First World War, its son John Reith would walk, feeling the winds of destiny brushing his cheek as they blew down from the Campsie Fells – or so he said. Even when a teenager, Reith, all six foot six of him, had a face with something of the Easter Island carving about it: graven, austere, immense jawed. As he aged, the dark bushy eyebrows became more wayward and independently active, the white hair wilder. There is footage of him being interviewed in 1967 by Malcolm Muggeridge. When the terrifying, wolfish smile comes, the face looks as if it has been hacked open with a hammer and chisel.

The church has now been converted into the premises of an accountancy firm and a business consultancy, which would horrify the intensely religious Reith: in his youth it resounded to sermons given by his father George, a Free Presbyterian minister whom the son worshipped second only to God the Father: ‘His sense of grace was apostolic;

his sense of righteousness prophetic,’ remembered Reith. ‘When he spoke on social or moral ill, or in defence of one whom he felt to be unjustly assailed, his eyes would flash; the eloquence of his indignation was devastating.’ The church ‘was one of the wealthiest, most influential, most liberal in Scotland’. Its congregation, in the British Empire’s prosperous, productive second city, encompassed ‘merchant princes, great industrialists, professors’ to a ‘considerable element of the humble but equally worthy sort – master tradesmen and foremen from shipyards and works …’ There was also a church mission that reached beyond Reith’s well-heeled parish to ‘a poor section of the city’: this was a self-conscious embrace of the whole social scale.

Reith grew up in an atmosphere of rigid piety. His parents were distant idols, seen only at mealtimes. At school, he did not flourish; he was removed from the Glasgow Academy after bullying two classmates, and sent to board at Gresham’s in Norfolk, where, eventually, he did better. But, to his bitter regret, his academic record was considered insufficient for university, and his father, calling him into his study one day, announced that he should follow a trade. He was duly apprenticed at an engineering firm. When war broke out in 1914, he joined up, and proved himself a bloody-minded and occasionally insubordinate soldier. One morning in France in 1915, when he was out inspecting a damaged communications trench, his tall and conspicuous figure was found to be a convenient target for a sniper. Part of the left side of his face was shot off, leaving a jagged scar. Relieved thereafter from active service, he spent happy and productive months in America as an inspector of small arms being produced for the war effort.

John Reith. ‘He would look through you … like a dowager duchess meeting a chimney sweep.’

By the autumn of 1922, Reith was unexactingly employed as honorary secretary to the Conservative politician Sir William Bull. According to the account in Reith’s autobiography, on 13 October, while scouring the newspapers, an advertisement caught his eye in the situations-vacant column. It read: ‘The British Broadcasting Company (in formation). Applications are invited for the following officers: General Manager, Director of Programmes, Chief Engineer, Secretary. Only applicants having first-class qualifications need apply. Applications to be addressed to Sir William Noble, Chairman of the Broadcasting Committee, Magnet House, Kingsway, wc2.’ Reith wrote an application and dropped it into his club’s post box – then thought to read Noble’s entry in

Who’s Who

, and fished

out his letter, rewriting it to emphasise his Aberdonian ancestry in an attempt to appeal to his putative employer’s local loyalties. His interview consisted of ‘a few superficial questions’, he recalled in his memoir,

Into the Wind.

He added: ‘I did not know what broadcasting was.’ Many might have quailed in the face of their own ignorance, but not Reith. Not long before, having listened to an especially energising sermon at the Presbyterian church in Regent Square, Bloomsbury, he had written in his diary, ‘I still believe there is some great work for me to do in the world.’

He was duly appointed general manager, and for the next few days, still in utter ignorance of what his new job might be, tried to ‘bring every casual conversation round to “broadcasting”’ until an acquaintance enlightened him. On 22 December 1922 he turned up at the offices (deserted, as it was a Saturday). He found ‘a room about 30 foot by 15, furnished with three long tables and some chairs. A door at one end invited examination; a tiny compartment six foot square; here a table and a chair; also a telephone. ‘“This”, I thought, “is the general manager’s office.”’ (‘Little more than a cupboard,’ remembered Peter Eckersley, the BBC’s first chief engineer.) Including Reith, there were four members of staff.

The BBC today, with its workforce of 21,000 and its income of £5 billion, is such an ineluctable part of British national life that it is hard to imagine its birth pangs, comparatively recent as they are. The birth of the BBC outstrips my own parents’ lifetimes by only a decade: for them, television was a novelty that became an affordable part of everyday life only in their adulthoods. (One of my father’s

most vivid early memories was the announcement on the wireless from Neville Chamberlain, on 3 September 1939, that ‘This country is at war with Germany’ – ‘followed shortly afterwards by the air-raid sirens and sitting in the pantry under the stairs waiting for the onslaught’, which, disappointingly for a seven-year-old, did not materialise.) The BBC’s sounds, its magical moving pictures, its words are not just ‘content’, as the belittling word of our time has it, but the tissue of our dreams, the warp and weft of our memories, the staging posts of our lives. The BBC is a portal to other worlds, our own time machine; it brings the dead to life. With it we can range across the earth; we can dive to the depths of the ocean; take flight. Once a kindly auntie’s voice in the corner of the room, it is now the daemonic voice in our ear, a loving companion from which we need never be parted. It is our playmate, our instructor, our friend. Unlike Google and Amazon, which soothe us by presenting us with the past (their profferings predicated on our web ‘history’), the BBC brings us ideas of which we have not yet dreamed, in a space free from the hectoring voices of those who would sell us goods. It tells seafarers when the gales will gust over Malin, Hebrides, Bailey. It brings us the news, and tries to tell it truthfully without fear or favour. It keeps company with the lonely; it brings succour to the isolated. Proverbially, when the bombs rain down, the captain of the last nuclear submarine will judge Britain ended when Radio 4 ceases to sound.

The year the BBC was born was also the year Northern Ireland seceded from the Free State; it was the year James Joyce’s

Ulysses

was published; and its creation was

sandwiched between the first general election in which women voted (1918) and universal suffrage (1928). Born in the wake of calamitous war, in the high noon of empire, and at the moment of the formation of the United Kingdom as we know it, it took its place as a projection of, and a power in, new ideas about nationhood, modernity and democracy. With the coming of the BBC, it became possible for the first time in these islands’ history for a geographically dispersed ‘general public’ to be able to experience the same events simultaneously – and together to gain what had hitherto been privileged access to the most powerful voices of the land.

This sense of collective experience, so familiar now, was striking and strange at its birth. Malcolm Muggeridge, in his book

The Thirties

(1940), tried to express the novel sense of the BBC thus: ‘From nine million wireless sets in nine million homes its voice is heard nightly, giving information, news, entertaining and instructing, preaching even, with different accents yet always the same; the voices of the nine million who listen merged into one voice, their own collective voice echoing back to them.’ He also marvelled, darkly, at the gulf between the nature of the news the wireless brought from the world outside – all delivered in reasonable, calm BBC tones – into the haven of the home. One thing came after another, spooling out of the wireless in an endless, undifferentiated stream of sound-matter. ‘Comfortable in armchairs, drowsing perhaps, snug and secure, the whole world was available, its tumult compressed into a radio set’s small compass. Wars and rumours of wars, all the misery and passion of a troubled

world, thus came into their consciousness, in winter with curtains drawn and a cheerful fire blazing; in summer often out of doors, sprawling on a lawn or under a tree, or in a motorcar, indolently listening while telegraph poles flashed past. Dollfuss had been murdered, despairing Jews had resorted to gas ovens … and the king and queen had received a warm welcome in Hackney – well, there it was, and now for another station …’

Reith recognised one of the most fundamental qualities of broadcasting: it is superabundant. It knows no scarcity; it cannot run out: ‘It does not matter how many thousands there may be listening; there is always enough for others’, as he put it in his 1924 book

Broadcast Over Britain

. ‘It is a reversal of the natural law, that the more one takes, the less there is for others … There is no limit to the amount that may be drawn off.’ And because everyone can have as much as they like of it, broadcasting, at least as delivered by the fledgling BBC, is no respecter of persons; it is the same for everyone: ‘Most of the good things of this world are badly distributed and most people have to go without them. Wireless is a good thing, but it may be shared by all alike, for the same outlay, and to the same extent … The genius and the fool, the wealthy and the poor listen simultaneously … there is no first and third class.’ Broadcasting, said Reith, had the effect of ‘making the nation as one man’. It was Reith who attached this Arnoldian, culturally unifying ideology to the idea of broadcasting. This ideology, despite the optimism of American broadcasting pioneers such as the engineer David Sarnoff, who in June 1922 wrote of wireless’s function as ‘entertaining, informing and

educating the nation’, was lacking in the United States, which was in the grip of a wireless craze by the mid-1920s. There, a cacophony of competing commercial stations grew up, strung between coast and coast. By 1925 there were 5.5 million American wireless sets and 346 stations.

That the BBC should have been set up as a company and a monopoly, and then a corporation in the public interest, was not inevitable, but the result of a series of incremental decisions at first pragmatic and then solidified into ideology. And before broadcasting was armoured in Reithian principles, it was first a technology. In the village of Pontecchio Marconi, a few kilometres south of Bologna in central Italy, is the remarkable sight of Guglielmo Marconi’s mausoleum, a kind of manmade travertine cave hewn into the rolling lawns of the Villa Griffone, the elegant nineteenth-century house he shared with his Scots-Irish wife Annie Jameson, scion of the Jameson whiskey empire. An enthusiastic fascist in later life, Marconi was accorded a state funeral by Mussolini, and his tomb has all the pomp – and distinctive, ruggedly geometric style – associated with the aesthetics of that regime. ‘

Diede con la scoperta il sigillo a un’epoca della storia umana

,’ declares the epitaph inside the monument, itself a phrase from the speech Mussolini gave after his death. It translates: ‘With his discovery he set his mark upon an era of human history.’

In truth, in the way of most scientific discoveries, it was a cluster of advances by a number of researchers that led the way to broadcasting. It was the German Heinrich Hertz who, before he died aged only thirty-six in 1894, demonstrated

the existence of electromagnetic waves. In 1902 an American, R. A. Fessenden, used wireless waves to carry the human voice over the distance of a mile. The north Staffordshire-born Oliver Lodge developed a tuning device to control the wavelength of a receiver. There were French, American and Russian discoveries, too, in the years before the First World War. Wireless telegraphy and wireless telephony – sending signals or the voice ‘through the ether’ without wire or cable – was becoming a reality. Marconi coupled his celebrated transatlantic radio experiments with an eye for commercial opportunities and a talent for business. In 1897, he founded the Marconi Wireless Telegraph and Signal Company. He did so in Britain, because it seemed to him that radio could be commercially exploited as a means of communications to shipping – and Britain was the great marine mercantile nation. Broadcasting – the notion of one voice speaking to many – was not yet recognised as a prospect in view, and certainly not as a virtue of the technology. As Asa Briggs pointed out in the first of his magisterial five volumes on the history of British broadcasting, the notion that radio signals could be heard widely was at first regarded as a ‘positive nuisance’, a hindrance to what was regarded as wireless’s most likely application in point-to-point communication. Briggs quoted Lodge, in a parliamentary select committee report of 1907, making the first small intellectual gropings towards something different – that it might have a purpose for ‘reporting races and other sporting events, and generally for all important matters occurring beyond the range of the permanent lines’.