This New Noise (10 page)

Authors: Charlotte Higgins

Being DG is also importantly about setting the tone, about selecting the rhetoric. ‘I for example want things that are bold and feel that we’re really pushing boundaries, I don’t want things which are safe and dull and placid, I really do want things that make you feel, “bloody hell, the BBC did that, that’s fantastic” … I’m spending at least a day a week out with programme-makers because I feel they’re the important, the frontline troops, the people that matter, the people that make the decisions and have the ideas that people pay their licence fee for,’ said Hall.

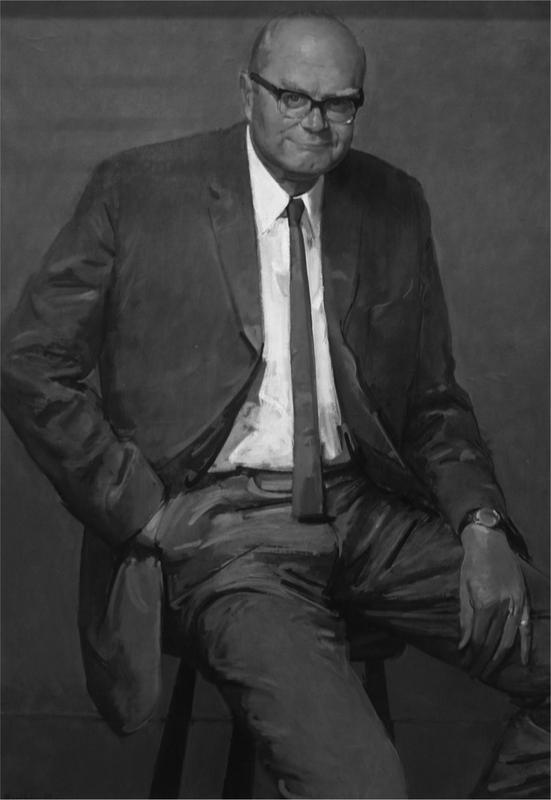

Hugh Carleton Greene: DG 1960–69 and ‘psychological warrior’ (portrait by Ruskin Spear)

As we spoke, I realised that Hall’s office was filled with images of his predecessors. Its glass walls were imprinted with oversize, multiple portraits of the first director general: I counted eight giant Reiths bearing ferociously down on him. On a wall was a painting of Sir Hugh Carleton Greene, director general 1960–69, which once hung with the others in the council chamber. Hall said that he used to find it comforting when he was called in for ‘a bollocking’ by the board when he was the BBC’s head of news. This is the image that Hall has chosen – this is the ancestor he has elected as his own.

Greene, like Reith and Birt, was a giant of a man, at almost six foot six inches. His portrait shows him sitting, in genially informal pose, on a high stool, his right hand in his pocket. He is slightly stooped, as very tall people often are, and just a touch crumpled. The painting conveys a faint loucheness – quite different, in fact, from Hall, who exudes the kind of reassuring, polite formality one might associate with a family solicitor or dentist.

Hall’s most obvious intellectual ancestor is in fact his former boss Birt. It was Birt who plucked him from the ranks to take control of BBC television news at the age of just thirty-six. It was under Birt that he acquired the reputation of being the older man’s ‘head prefect’, an ultra-loyalist prepared to take on the painful and unpopular task

of reforming the BBC’s newsroom. But in his admiration of Greene he is attempting to connect with the more creative part of himself, the part that he has brought with him from the Royal Opera House. Greene’s BBC was defiantly modern: his was the era of BBC2,

Z-Cars, Doctor Who

and the deference-slaying satirical show

That Was The Week That Was.

‘I wanted to open the windows and dissipate the ivory-tower stuffiness which still clung to some parts of the BBC,’ Greene wrote in his book

The Third Floor.

‘I wanted to encourage enterprise and the taking of risks. I wanted to make the BBC a place where talent of all sorts, however unconventional, was recognised and nurtured, where talented people would work and, if they wished, take their talents elsewhere, sometimes coming back again to enrich the organisation from which they had started.’

Greene is, in the words of BBC historian Jean Seaton, ‘the broadcaster’s broadcaster. But the absolute key thing about Greene was that he was what I’d call an amphibian. He was that generation of men who had worked in government during the war’. Greene, the son of the headmaster of Berkhamsted School, began his career as a reporter. As head of the

Telegraph

’s Berlin bureau, he was the last British journalist to leave the city before the war. After being called up to the air force, where he became an intelligence officer, he was seconded to the BBC to work in German-language propaganda broadcasting. He described his role as ‘deceiving, taunting but most of all and most important of all giving the enemy hard news even of our defeats, so that when, as one hoped, the time came for victories, they would believe what we said’. He wrote, ‘To a German

audience used to the most unscrupulous lies from its own press and radio we had to put ourselves across as strange beings who were really interested in truth even when the truth was, as it continued to be for many, many months, almost entirely to our apparent disadvantage.’

He had lived through a great deal. Speaking on

Desert Island Discs

, he recalled liberated Dachau: ‘There was an incinerator, a big hall piled with corpses round an enormous stove and the notice was up in this big hall saying “

Reinlichkeit ist hier Pflicht, bitte Hände waschen

” – cleanliness is a duty here, please wash your hands. But the living skeletons in their striped pyjamas were in some way more difficult to bear than the dead. To have them kissing one’s hands, embracing one …’ Later, after the end of the war, he returned to the shattered Germany to help rebuild broadcasting there. These were the kind of experiences that made the travails of the BBC fall into some perspective when he became director general.

‘To be director-general of the BBC is a very interesting experience,’ he wrote in 1969. ‘I doubt whether there is a more fascinating job in the world. One must be an editor with a feeling for news. One has to have a knowledge of the arts … One must be an administrator. One may be the father of 23,000 people. One must know enough about engineering to be able to ask the right questions … One must be able to walk with confidence in the political corridors of power … And one is an inheritor of a tradition of truthfulness and reliability which leads people at home and in nearly every country of the world to turn to the BBC in times of trouble.’ Greene was an operator, a

politician. Early in his tenure he had to face the government’s Pilkington Committee on the future of broadcasting. He ran the BBC’s campaign like a propaganda offensive: the case was meticulously researched, the committee was lobbied, rival ITV’s strengths and weaknesses were painstakingly assembled. It was ‘an exercise in psychological warfare and I confess that I found my experience as head of psychological warfare in Malaya in 1947 extremely useful’, he recalled, remembering one of his post-war government jobs, this time countering Chinese insurgents. The eventual report, published in 1962, tightened ITV regulation and strengthened the BBC, allowing it to launch its second, colour channel, and to launch its local radio network: a total victory.

Even Greene, though, could not stave off every assault. In the end, his confident 1960s BBC was seen to have run out of control. Looking back, he remembered his tenure thus:

I think the BBC’s output during these years … has brought out into the open one of the great cleavages in our society. It is of course a cleavage which has always existed: cavaliers versus roundhead, Sir Toby Belch versus Malvolio, or however you may like to put it. But in these years was added to that the split between those who looked back to a largely imaginary golden age, to the imperial glories of Victorian England and hated the present, and those who accepted the present and found it in many ways more attractive than the past.

Harold Wilson felt the corporation must be tamed, and deemed arch-Tory Charles Hill, who had chaired the Independent Television Authority, the ITV regulator, the man for the job. Hill was appointed chairman of the BBC: it was, remembered David Attenborough, like putting Rommel in charge of the Eighth Army. Greene did not last long. ‘He was as sacked as Alasdair Milne was sacked,’ according to Seaton. ‘Just not quite so brutally.’ The BBC, remembered Marcia Williams, Wilson’s right-hand woman, had been behaving ‘in the spirit of the independent empire that they had preserved for themselves’. In the end, even psychological soldiery was no safeguard against downfall.

Directors general are potentates: as grand as Medicis, their territories stretching as far and wide as kings’ domains, their armies battle-ready. But for all that, they are vulnerable creatures. A twist of a political dagger can destroy them. They are always subject to a higher power – the government. It is in the BBC’s nature for its dictatorship to be tempered by assassination. Hall may revere Greene, but his end is a warning.

It was in the brief interval between a board meeting and a governors' luncheon that Alasdair Milne, the director general of the BBC, was coolly deposed by the chairman, Marmaduke Hussey. Ros Sloboda, who was Milne's PA at the time, remembers that day â Thursday, 29 January 1987 â vividly:

He came down from the board meeting and into my little office at Television Centre. âRight,' he said, âthe chairman's asked to see me. I'll just pop in. Then I'm going straight to lunch, and afterwards I'll pick you up and we'll go back to Broadcasting House.' It must have been literally a minute later that he came back, and said, âI've been fired.' I looked at him and I said, âDon't be stupid.' And I laughed. And he said, âI'm not being stupid, Ros, they've fired me. They made me sign a piece of paper saying that I'm resigning for personal reasons, because they told me if I didn't sign it, it would affect my BBC pension. I'm going home now.' And he picked up his briefcase and went.

When I met Sloboda she was in the guise of the smartly dressed, no-messing personal assistant to Michael Grade, a role she had fulfilled for nearly thirty years. She exuded

the air of someone who had seen all of the creatures in the broadcasting zoo and had long since ceased to be amazed by their antics. Back in the 1980s she had been a skilled secretary who had worked her way up through the BBC ranks to the role of DG's secretary. She had worked in the BBC for twenty years, beginning as a young, green girl in 1960, typing contributors' contracts for

Housewives' Choice

under a superior secretary who âwore white gloves and big hats'. She remembered smuggling wodges of spoiled drafts out of the building on her first day for fear that someone would go through her waste-paper basket to check up on her errors.

Sloboda recalled that after Milne had left the building, she wandered dazedly into the room where the directors and governors of the BBC were preparing to have lunch. Hussey read out a brief statement. She remembered, âNot one of them said, “Chairman, just a moment, can we clarify? Alasdair's resigning? What are the personal reasons? What? Why didn't he tell his colleagues?” No one said a word. They all talked about where they were going on holiday. I found that quite â¦' She paused, then seemed to dismiss the possibility of finding the right word. âIt's the English way,' she concluded, drily. Milne, who was DG from 1982, died in 2014. He never came to terms with the manner of his dispatch.

There was, of course, much more to Milne's tenure than strife: TV and radio flourished, and most viewers' and listeners' experience of the BBC of the time is richer and deeper than the particular darkness that Sloboda recalls from within that lonely and âmassive, oak-panelled office

on the third floor of Broadcasting House'. None the less, she recalls the incoming fire as having been pretty constant through Milne's four-year director-generalship, which was certainly one of the most turbulent in the BBC's history. There were the libel cases arising from a 1984 edition of

Panorama

called

Maggie's Militant Tendency

, which claimed that the Conservatives had been infiltrated by elements of the far right; and there was the time Special Branch raided the BBC Scotland HQ after an investigation into the secret spy satellite system Zircon. There was a consistent sense of hostility and pressure from the Conservative government, within which there were zealots who would have seen the BBC privatised. And there was Milne's increasingly poisoned relationship with his board of governors; after the untimely death of the BBC's chairman Stuart Young in 1986, a Thatcher-approved replacement, Hussey, was inserted to bring the BBC to heel.

Sloboda described it like this: âIt was that terrible feeling you get when you first come home with a baby, and you don't know what you're doing. Events just always ran away with themselves. We were never in control of anything. It was terrifying, it was awful, it was absolutely exhausting. It was dreadful, absolutely dreadful. I've never worked in anything like that before or since.' She told me that she'd recently had lunch with George Entwistle's former PA. âAnd she was saying how awful it had been, and I said to her, “Just think, you had 54 days of it. I had four years of it.” Something else was always about to happen.'

In truth, it has always been that way, to a greater or lesser degree. The BBC is a battlefield that can be grim and

dark and strewn with human wreckage. It is where the British gather to fight their most vicious culture wars. The BBC's particular and paradoxical relationship with governments â funded as it is by a politically negotiated charter, independent as it strives to be in its journalism â has meant it is caught up in dynamics of high power to a greater extent than any other British broadcaster. It has always ricocheted from trouble to trouble, and it has crisis in its bones, back to 1926 when it survived a dogfight with Churchill over its coverage of the General Strike. In 2004 its DG and chairman, Greg Dyke and Gavyn Davies, resigned after a battle over the claim, made on the

Today

programme, that the government had deliberately exaggerated the threat posed by Saddam Hussein's weaponry in the run-up to the Iraq war â a crisis that crushed the source of the story, the weapons expert Dr David Kelly, into the unthinkable bleakness of suicide.

Alasdair Milne at Television Centre. He was DG from 1982 until his defenestration in 1987.

For Milne the squall over a documentary about Northern Ireland in 1985 was emblematic. It was shortly after Thatcher had declared that the IRA should be denied âthe oxygen of publicity' â this was four years before the then home secretary, Douglas Hurd, would order a âbroadcast ban' on organisations believed to promote terrorism, meaning that for six years viewers and listeners heard actors voicing the words of Sinn Féin members. A

Sunday Times

journalist, having caught wind of a BBC documentary in which Martin McGuinness was to appear, asked the prime minister at a press conference how she would react if a broadcaster was planning to show an interview with a leading member of the IRA. She replied in unsurprisingly strong terms.

All hell broke loose: on 29 July Leon Brittan, the home secretary, wrote a furious letter to the BBC declaring that the programme should not air â though, naturally, he had not seen it. âThe BBC would be giving an immensely valuable platform to those who have evinced an ability,

readiness and intention to murder indiscriminately its own viewers,' he wrote. Milne was in Finland at a conference, about to start a holiday in Sweden. In those days before instant communications, Sloboda remembers finding the telephone number of the night steamer from Helsinki to Stockholm, and organising a Tannoy announcement to summon him to the telephone. âI said, “Alasdair, have you ever heard of a programme called

Real Lives

?” He said, “No.” And I said, “Well, there's a spot of bother.”'

The BBC governors called an emergency meeting. With Milne still in Sweden, and his deputy Michael Checkland at the helm, they decided to view the programme before transmission. This was against all custom and practice: the governors' stated role was to set the broad policy of the corporation rather than to interfere in executive decision-making. In declaring it should not be aired, they pushed staff into open rebellion, and a strike was called. Michael Grade, then the BBC's director of programmes, remembered in his memoir the reaction among BBC employees: âWe felt betrayed by the people who had been appointed to protect our independence: they had buckled in the face of a blatant attempt by the Thatcher government to censor the BBC.'

When Milne returned five days later, having taken the decision, surely unthinkable today, not to cut short his holiday, he told the governors the programme was transmittable with only minor changes, and that he planned to say so publicly. His position â open and bloody-minded defiance of the governors â was regarded by Young as âa resignation statement or a firing statement', according

to the minutes of what was clearly a thunderously ill-tempered board meeting.

The documentary was eventually aired on 16 October, with minor changes. As the

Guardian

's Belfast correspondent pointed out at the time, the reality of the programme was rather different from the fantasy. âIt was ⦠generally agreed that the film, although well made, contained nothing new,' wrote Paul Johnson rather quellingly of an early, unofficial screening rigged up on the pavement outside the BBC's Belfast HQ by âenterprising journalists' who had filched a tape of the documentary. Nancy Banks-Smith wrote in her review of the programme, âInconceivable that anyone should want to blow its head off. It is a lovely, sad quiet thing.'

On the day following its official transmission

Guardian

columnist Hugo Young refused to believe that the matter had been decently settled by the fact of the broadcast, and wrote eloquently of the wounds the affair had opened. âThe episode remains an indelible disaster. It shows how numerous are the enemies of truth-telling, how dangerous is the governors' conception of their task and how vulnerable television is to special rules and pressures which get in the way of it doing its job. The film has been shown, but it leaves the fragile threads of the BBC's integrity all but broken,' he wrote.

The film has been broadcast again only once. I was allowed to view it only under supervision in the editorial policy office (the unit responsible for patrolling the ramparts of standards and balance in BBC programmes). Virtually free from editorialising or voiceover,

Real Lives: At

the Edge of the Union

offers up two parallel lives, that of McGuinness and his Democratic Unionist opposite number, Gregory Campbell, in long, uninterrupted interviews. What is striking is the sophistication and confidence of producer Paul Hamann's construction of the documentary; what is shocking is not that either subject might particularly advance his cause, but that each talks war and death amid utterly ordinary, and strikingly similar domestic existences â romping around on the beach with the kids, pouring milk from china jugs into cups of tea.

*

If one thing is certain about the BBC, then it is that crisis will always be around the corner. Its enemies are on the hunt, constantly â any mistake, any hesitation, and the predators pounce. From the outside, the corporation, despite decades of handling such moments, has frequently seemed uncertain and clumsy in managing them, often travelling from an initially sluggish response towards an exaggerated (though some might say ineffective) display of public self-laceration. One recently retired BBC employee deprecated, for example, the entire BBC culture of post-calamity enquiries. âWas it a whopper of an editorial mistake?' she asked of the BBC's failure to pursue, in 2011, a

Newsnight

investigation into abuse allegations against Jimmy Savile. âYes, it clearly was a whopper of an editorial mistake. But you didn't need to spend £2 million and [hire] barristers and Nick Pollard [the former head of Sky News, who conducted an investigation] to uncover that.'

Hindsight is a wonderful thing. The events that led to the resignation of Entwistle as director general of the BBC

on 11 November 2012 look fairly straightforward, from the outside and after the passage of years. A decision by the editors of

Newsnight

in December 2011 not to pursue allegations of sexual abuse against Savile led to the suggestion, in January 2012, that the BBC had conspired to drop the report to protect its Christmas tribute to the entertainer. Then, on 3 October, an ITV investigation into Savile was broadcast, prompting Entwistle to commission the report from Pollard into why

Newsnight

had stopped its own investigation. Separately, on 2 November,

Newsnight

broadcast claims by Steve Messham that, as a child in care in Wales in the 1980s, he had been sexually abused by a prominent political figure â a figure wrongly identified online, in the hours leading up to the broadcast, as the former chairman of the Conservative party, Lord McAlpine. This led to the spectacular departure of its DG after only 54 days in post.

All of that is easy to write: real life is not so simple. The crisis did not feel linear, like a row of dominoes. It was a complicated tapestry of events, in which a thread pulled loose in one part of the elaborate pattern affected the whole. Seemingly small decisions made by not terribly senior people had consequences that affected the entire corporation. According to Professor Charlie Beckett, founder of Polis, the journalism think tank at the London School of Economics, âIt was like a medieval medicine chart. The humours, the flows, were radically dysfunctional.'

But what if you were there? What did it feel like to try to survive the tempest as the waves crashed over your head? Much had changed since the 1980s. The pace of

news had accelerated. There was the 24-hour news cycle: BBC executives at the centre of the SavileâMcAlpine stories found their houses surrounded by reporters and cameras, feeding a ravenous monster that they themselves had reared. There was the echo chamber of Twitter: one of the catastrophes of the McAlpine story was that tweets started to appear before the screening of the report, causing speculation to coalesce around McAlpine as the probable public figure whom Messham had identified, mistakenly, as his past abuser. âAs soon as I saw that first tweet,' said one

Newsnight

staffer, âI knew I'd lost my job.'