There is No Alternative (13 page)

Read There is No Alternative Online

Authors: Claire Berlinski

His last name presents another challenge. I have been told that he pronounces it

Pole

, but his brother Jonathan pronounces it

Powell

, to rhyme with

towel

. His brother was Tony Blair's chief of staff. I am not sure what to make of this but suspect it is evidence for the claim that they are all Thatcherites now. Left-leaning British newspapers, unable to find much to distinguish between the brothers politically, have fixated on their names; they declare the pronunciation

Pole

pretentious. As I offer him my hand, I worry that I've gotten it mixed up. Which is the pretentious pronunciation again, and which one is he?

Pole

, but his brother Jonathan pronounces it

Powell

, to rhyme with

towel

. His brother was Tony Blair's chief of staff. I am not sure what to make of this but suspect it is evidence for the claim that they are all Thatcherites now. Left-leaning British newspapers, unable to find much to distinguish between the brothers politically, have fixated on their names; they declare the pronunciation

Pole

pretentious. As I offer him my hand, I worry that I've gotten it mixed up. Which is the pretentious pronunciation again, and which one is he?

“So nice to meet you,” I say.

“And you,” he replies.

The interchange offers no clues about his name. His part of it suggests that he may well be uncertain of mine.

Powell was Thatcher's closest advisor, “the second most powerful figure in the Government,” writes her biographer John Campbell, “practically her

alter ego

.”

48

Powell and American National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft shared a secure line to each others' phones. Scowcroft called Powell directly when he needed to talk to Britain. Powell was, according to Scowcroft, “the only serious influence” on Thatcher's foreign policy.

49

Powell's status as the prime minister's pet was greatly resented. Alan Clark, Thatcher's defense minister and an infamously indiscreet diarist, recalls the vexation of another close Thatcher advisor, Ian Gow, who lamented “the way the whole Court had changed and Charles Powell had got the whole thing in his grip.”

50

The ever-irritable Nigel Lawson, Thatcher's chancellor, was equally dismayed by Powell's overweening influence: “He stayed at Number 10 far too long.”

51

Everyoneâwhether or not they liked himâagrees that Charles Powell is a highly intelligent man.

alter ego

.”

48

Powell and American National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft shared a secure line to each others' phones. Scowcroft called Powell directly when he needed to talk to Britain. Powell was, according to Scowcroft, “the only serious influence” on Thatcher's foreign policy.

49

Powell's status as the prime minister's pet was greatly resented. Alan Clark, Thatcher's defense minister and an infamously indiscreet diarist, recalls the vexation of another close Thatcher advisor, Ian Gow, who lamented “the way the whole Court had changed and Charles Powell had got the whole thing in his grip.”

50

The ever-irritable Nigel Lawson, Thatcher's chancellor, was equally dismayed by Powell's overweening influence: “He stayed at Number 10 far too long.”

51

Everyoneâwhether or not they liked himâagrees that Charles Powell is a highly intelligent man.

Given the descriptions I have read of him, I am expecting to encounter a suave, gregarious personality, but instead I find him a man of subdued affect. He is correct and courteous, but as we speak, I worry that I am failing to draw him out. Only later, when I transcribed the interview, did I realize that the language he used to describe the former prime minister was passionate.

“Tell me about your first impression of her,” I say. “I understand that you first met her when you were waiting with your wife for the by-election results in Germanyâ”

“That's right, yesâwe were in the embassy in Germany. She came out to see Schmidt and Kohl.

52

She was quite recently elected in the Opposition. Well, I think it was of this tremendous energy and zest, we'd got pretty used to this procession of rather dispirited politicians, of all three parties, trooping through Germany lamenting Britain's decline and so on, and here, suddenly, there was this woman, of whom we knew little at the time, who seemed to believe it could all be changed. It just needed

her

to be in power to bring about this tremendous change. It was invigorating.”

52

She was quite recently elected in the Opposition. Well, I think it was of this tremendous energy and zest, we'd got pretty used to this procession of rather dispirited politicians, of all three parties, trooping through Germany lamenting Britain's decline and so on, and here, suddenly, there was this woman, of whom we knew little at the time, who seemed to believe it could all be changed. It just needed

her

to be in power to bring about this tremendous change. It was invigorating.”

Energy, zestâeveryone uses those words. She famously required no more than four hours of sleep at night. “She hated holidays,” Powell recalls. “She

loathed

holidays; she didn't like weekends, because they were a bit of an interruption, but that was all right because she could pretend they didn't exist by continuing working at Chequers, and making some of the rest of us work at Chequers, but holidays, after two days she was on the telephone, looking for excuses to come back to London.”

53

loathed

holidays; she didn't like weekends, because they were a bit of an interruption, but that was all right because she could pretend they didn't exist by continuing working at Chequers, and making some of the rest of us work at Chequers, but holidays, after two days she was on the telephone, looking for excuses to come back to London.”

53

“Would you describe the environment around her as tense?”

“The environment around her was

boiling

. A permanent state of everything sort of red hot. Like some kind of lava coming out of a volcano. It really was.”

boiling

. A permanent state of everything sort of red hot. Like some kind of lava coming out of a volcano. It really was.”

Â

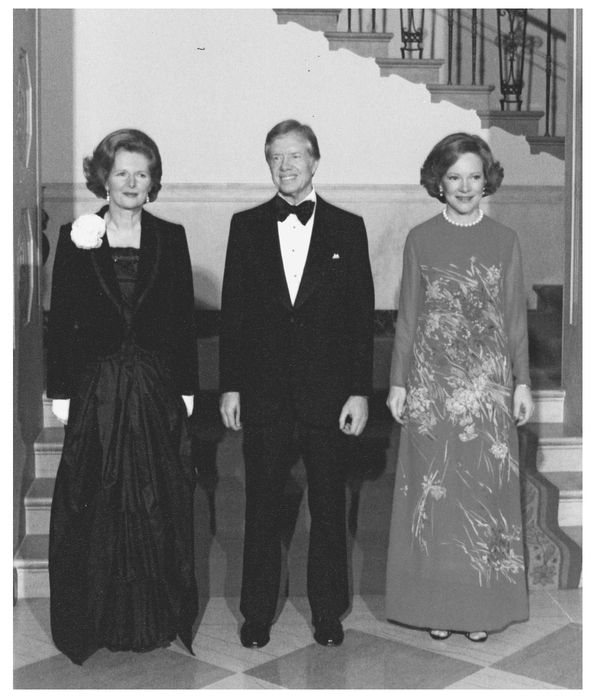

This image of Thatcher, visiting the White House in 1979, conveys the old-fashioned movie-star glamour she could project when it suited her purposes. If you did not know this was the new prime minister of Britain, you could easily imagine this woman sweeping regally into the Kodak Theater to collect an Oscar for lifetime achievement.

“Did you like being around that?” The man before me is sedate, his hands folded primly in his lap. It is hard to imagine that a boiling environment would be to his taste.

“Well, it was pretty invigorating, but really tiring.”

I'll bet.

I ask him to tell me more about the way Margaret Thatcher looked to him, back in those early days. “Her posture was always upright,” he says. “She was very, very stiff-backed and upright, and she was always very tidy as well. A lot of British politicians are very sloppy, in their dress and so onâI don't want to actually name any names or be discourteous, but you can probably think of quite several, female as well as male. But she was always meticulous in her dress, and perhaps some of her earlier styles look a bit fussy now, but once she got into the power-suit dressing it was all part of it. She was reallyâyou've got to think in terms of Margaret Thatcher Productions, almost, I mean there were the policies and the rhetoric, but there was also the hair, the dress, the lighting, and everything. She could have tremendous dramatic effect on the platform, whether at a party conference speech or a speech to a joint session of the U.S. Congress. It was all packaged. It was almost like a great diva, giving a performance.”

He is right. Margaret Thatcher often seemed like an exceptionally gifted actress playing the role of Margaret Thatcher. On television, she fills the screen. The eye is ineluctably drawn to her, so that everything and everyone else in the frame is dwarfed by comparison. Hollywood executives call this quality

It

. Marlon Brando had

It

, and so did Marilyn Monroe. But neither of them had nuclear weapons.

It

. Marlon Brando had

It

, and so did Marilyn Monroe. But neither of them had nuclear weapons.

Let's look at one of those Margaret Thatcher Productions in slow-motion. Part of it is on YouTube, in a clip titled “Margaret Thatcher Talking about Sinking the

Belgrano.

”

54

During the Falklands War, Britain declared a two-hundred-mile exclusion zone around the islands, warning that any Argentine ship within the zone was subject to destruction. The Argentine cruiser

Belgrano

was outside this zone, sailing away from the islands. Thatcher or-dered

it sunk nonetheless. The attack killed 323 Argentine sailors. An outcry over the carnage ensued, in Britain and abroad; some charged that this was a war crime. Whatever you may think about the sinking of the

Belgrano,

do note this: The Argentine navy thereafter refused to leave port.

Belgrano.

”

54

During the Falklands War, Britain declared a two-hundred-mile exclusion zone around the islands, warning that any Argentine ship within the zone was subject to destruction. The Argentine cruiser

Belgrano

was outside this zone, sailing away from the islands. Thatcher or-dered

it sunk nonetheless. The attack killed 323 Argentine sailors. An outcry over the carnage ensued, in Britain and abroad; some charged that this was a war crime. Whatever you may think about the sinking of the

Belgrano,

do note this: The Argentine navy thereafter refused to leave port.

Here is Thatcher, responding to critics who have charged her with obfuscating the circumstances leading to the decision to sink the

Belgrano.

She is in the television studio with interviewer David Frost, an ordinarily articulate man who is not known for backing away from power but who in her presence appears oddly goofy. Her hair is sprayed into a stiff golden helmet; not a strand is out of place. Her rouge is flawless. Pale lipstick highlights a mouth that on another face might be described as sensuous. She is wearing pearl earrings; the broach on the lapel of her stern navy suit complements her blouse. The effect, as Powell said, is immaculately tidy.

Belgrano.

She is in the television studio with interviewer David Frost, an ordinarily articulate man who is not known for backing away from power but who in her presence appears oddly goofy. Her hair is sprayed into a stiff golden helmet; not a strand is out of place. Her rouge is flawless. Pale lipstick highlights a mouth that on another face might be described as sensuous. She is wearing pearl earrings; the broach on the lapel of her stern navy suit complements her blouse. The effect, as Powell said, is immaculately tidy.

David Frost:

On that day, when the Government said it changed direction many times, it only changed direction once to go back home and a 10-degree difference to get closer to Argentinaâ

On that day, when the Government said it changed direction many times, it only changed direction once to go back home and a 10-degree difference to get closer to Argentinaâ

Prime Minister:

A ship is torpedoed on the basis that

if

wherever she is she can get back to sink your ships in reasonable time, you do not just

discover

ships on the high seas and keep track of them the entire time. You can lose them. You can lose them. I would far rather have been under the attack I was for the

Belgrano

than under the attack I might have been under for putting the

Hermes

or

Invincible

in danger, and if ever you think that governments have to reveal every single thing about ships' movements, we do not! And if I were tacklingâ

A ship is torpedoed on the basis that

if

wherever she is she can get back to sink your ships in reasonable time, you do not just

discover

ships on the high seas and keep track of them the entire time. You can lose them. You can lose them. I would far rather have been under the attack I was for the

Belgrano

than under the attack I might have been under for putting the

Hermes

or

Invincible

in danger, and if ever you think that governments have to reveal every single thing about ships' movements, we do not! And if I were tacklingâ

DF:

No, but I mean, the reason people getâ

No, but I mean, the reason people getâ

Prime Minister:

âin charge of a war again, I would take the same decision again . . . Do you think, Mr. Frost, that I spend my days prowling round the pigeonholes of the Ministry of

Defense to look at the chart of each and every ship? If you do you must be bonkers!

âin charge of a war again, I would take the same decision again . . . Do you think, Mr. Frost, that I spend my days prowling round the pigeonholes of the Ministry of

Defense to look at the chart of each and every ship? If you do you must be bonkers!

DF:

No! Come back to theâ

No! Come back to theâ

Prime Minister:

Do you think I keep in my headâ

Do you think I keep in my headâ

DF:

âwhen you said to Mrs. Gould

55

âwhen you said to Mrs. Gould on the election program before the election in '83 that it was not sailing away from the Falklands, you had known from November '82 that it was!

âwhen you said to Mrs. Gould

55

âwhen you said to Mrs. Gould on the election program before the election in '83 that it was not sailing away from the Falklands, you had known from November '82 that it was!

Prime Minister:

What I said to Mrs. Gould was, “If you think that I know in detail the passage of every blessed ship I cannot think what you think the Prime Minister's job is!”

56

What I said to Mrs. Gould was, “If you think that I know in detail the passage of every blessed ship I cannot think what you think the Prime Minister's job is!”

56

You may tune in on YouTube to see the rest. Study the voice: Like a trained stage actress, she projects from the chest and uses the full range of her vocal register. Her body remains still; she does not fidget or shift or even gesture. Note the varied rhythm of her speechâone moment slow and deliberate, the next insistent and percussive. “What I know, Mr. Frost,” she saysâand she pronounces his name,

Mr. Frost

, as if a

Mr. Frost

is some thoroughly disgusting species of bugâ“is that the ministers have

given

the information to the House of Commons. They said that

one

thing was not correct. I was the

first

to say, âRight,

give the correct information

.' And the correct, and

deadly

accurate information was given.” The word “deadly” flows easily from her tongue. She is leaning forward, intense, alert. Her eyes are blazing. You are looking at a woman who has given the order to kill 323 young Argentine men, and her glowing complexion suggests that this has not troubled her sleep one bit. Indeed, she looks as if she has had an exceptionally good night's rest.

Mr. Frost

, as if a

Mr. Frost

is some thoroughly disgusting species of bugâ“is that the ministers have

given

the information to the House of Commons. They said that

one

thing was not correct. I was the

first

to say, âRight,

give the correct information

.' And the correct, and

deadly

accurate information was given.” The word “deadly” flows easily from her tongue. She is leaning forward, intense, alert. Her eyes are blazing. You are looking at a woman who has given the order to kill 323 young Argentine men, and her glowing complexion suggests that this has not troubled her sleep one bit. Indeed, she looks as if she has had an exceptionally good night's rest.

“But

I

do not spend my days,” she continuesâin response to a question he has not askedâ“

prowling

around the pigeonholes of the Ministry of Defense looking at the precise course of action.” She says

I

as if the

I

in question is something magnificent, and the very hint that such a vital magnificenceâ

Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher

, the human embodiment of the British people and their destiny!âwould do something as lowly as

prowl

(never mind that Mr. Frost never said this) is contemptible. There is now something like a bat squeak from Mr. Frost. “One moment!” she pronounces, lifting an imperious finger. “

One moment

!”

I

do not spend my days,” she continuesâin response to a question he has not askedâ“

prowling

around the pigeonholes of the Ministry of Defense looking at the precise course of action.” She says

I

as if the

I

in question is something magnificent, and the very hint that such a vital magnificenceâ

Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher

, the human embodiment of the British people and their destiny!âwould do something as lowly as

prowl

(never mind that Mr. Frost never said this) is contemptible. There is now something like a bat squeak from Mr. Frost. “One moment!” she pronounces, lifting an imperious finger. “

One moment

!”

Mr. Frost tries haplessly to get a word in, fumbling with his papers. “Woodrow Wyatt says you only respect people whoâ”

57

57

“One moment,” she demands.

“Yes,” he says meekly and falls silent. Her voice is lower now, and all the more menacing for it. Given her expression you would not be entirely surprised to see laser beams shoot from her eyes and vaporize this disgusting Mr. Frost, bringing the death toll to a salutary 324. “That ship”âshe says this slowly, her mouth narrow, her voice full of controlled fury and contemptâ“was a danger to

our boys

.”

our boys

.”

Our boys

: These are in fact

men

she is talking about, every last one of them over the age of majority and armed with fearsome weapons, and the use of the word “boys” sounds at once fiercely maternalâa tiger protecting her cubsâand intensely patronizing.

Those

boys are our heroes, as all right-thinking men and women know, and you, Mr. Frost, are not fit to shine their shoes. But they are still

boys

, just as you, Mr. Frost, are a silly stripling. The lot of youâ

boys

. But you are

my

boys, and that is why despite your childish foolishness, I shall protect you and set you on the right course. “

That's

why that ship was sunk,” she says. “I

know

it was right to sink her.” A pause. Mr. Frost has gone mute. “

And I would

do

. . . the

same

. . .

again

.”

: These are in fact

men

she is talking about, every last one of them over the age of majority and armed with fearsome weapons, and the use of the word “boys” sounds at once fiercely maternalâa tiger protecting her cubsâand intensely patronizing.

Those

boys are our heroes, as all right-thinking men and women know, and you, Mr. Frost, are not fit to shine their shoes. But they are still

boys

, just as you, Mr. Frost, are a silly stripling. The lot of youâ

boys

. But you are

my

boys, and that is why despite your childish foolishness, I shall protect you and set you on the right course. “

That's

why that ship was sunk,” she says. “I

know

it was right to sink her.” A pause. Mr. Frost has gone mute. “

And I would

do

. . . the

same

. . .

again

.”

Other books

And So To Murder by John Dickson Carr

The Pagan Night by Tim Akers

The Dark Lady by Dawn Chandler

The Way Home by Becky Citra

Primal Shift: Episode 2 by Griffin Hayes

The World Unseen by Shamim Sarif

Under the Open Sky (Montana Heritage Series) by Maness, Michelle

Stewart, Angus by Snow in Harvest

Linda Ford by Cranes Bride

Shoot the Woman First by Wallace Stroby