There is No Alternative (10 page)

Read There is No Alternative Online

Authors: Claire Berlinski

The box appears to be made of something bombproof.

“What

is

it?” I ask.

is

it?” I ask.

“Come closer!”

I approach. The strange vessel appears to be emitting an aura. Andrew leans over, shielding from my glance the trick he uses to open it. It flips open noiselessly. He stands aside. “

Ta-da!”

Ta-da!”

There it is:

her handbag.

her handbag.

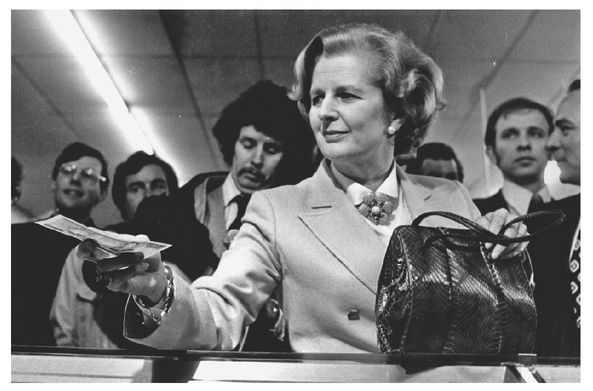

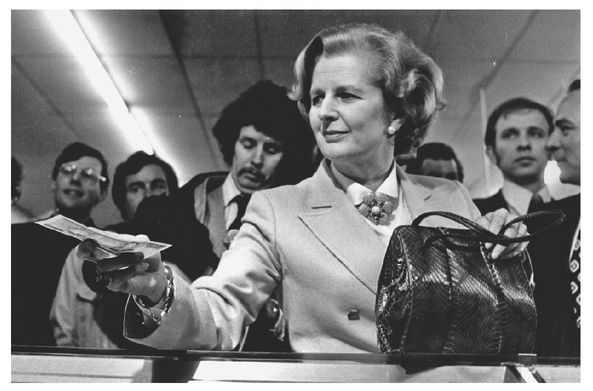

The thing is almost alive and pulsating. I half expect it to whiz up and begin soaring about the room. Thatcher famously opened a ministerial meeting by thumping that handbag on the table and announcing, “I haven't much time today, only enough time to explode and have my way.”

“Smell it,” says Andrew. He is flushed with sly delight.

“Can I? Really?”

“Go on.”

I lean over and sniff, gingerly. There is a faint odor of talcum and lily. I look at him, surprised. “It smellsâ”

“My grandmother wore a perfume that smelled

just like that.”

just like that.”

He's right. The handbag smells like a nice old lady.

I'm taken aback. I had been expecting it to smell like napalm and gunpowder.

Now we'll look at the documents. Have you washed your hands? Stored your belongings in the locker? You must place each paper flat on the table. Only one file at a time. Use a pencil to take notes, absolutely

not

a pen, and for God's sake, don't get the papers out of order.

not

a pen, and for God's sake, don't get the papers out of order.

Many of the documents are useless and mind-numbingly boring. “Tourism is an important growth industry in Wales,” that sort of thing. We'll skip those. The good stuff is in the pre-election strategy documents, the documents that show us just what Thatcher and those around her proposed to do and how their minds worked. This one, for example:

Britain under Jim Callaghan is far from an ideal society. Yet already the normal rosy hues that proceed [sic] an election are being painted by the Labour Government. Even the IMF are springing to their aid. We must counteract this propaganda. We shall do this by painting what we believe to be the true picture of “Jim's Britain.” This is a very ugly society and we believe the following words characterize it: selfish, cruel, irresponsible, evil, unjust, unfair, dishonest, secret, frightened, cowardly, lacking nerve, stupid, illogical, dull, unthinking, unreasonable, erratic, simplistic, hostile, hateful, ignorant, confused, poor, hesitant, short-sighted, blind, apathetic, bored, tired, pessimistic, unfulfilled. In other words we have an immature society where individuals deny responsibility to each other. Both they and their country seem to have lost faith in themselves. There is no appearance of personal growth, no fulfillment of satisfaction for self, children or indeed the whole family. No sense of pride, no sense of patriotism.

Â

Thatcher was particularly gifted at spotting opportunities subliminally and overtly to convey that she was above all a thrifty housewife who did the family shopping, knew how much groceries cost, and understood how deeply rising prices affected the ordinary British family. (Contrast this with the elder George Bush, who was reportedly baffled by the sight of a supermarket scanner.) Her policies, she intimated repeatedly, were nothing more than common-sense household economics writ large.

(Courtesy of the family of Srdja Djukanovic)

(Courtesy of the family of Srdja Djukanovic)

We shall contrast Jim's Britain with the normative model of Britain's ideal society that Tory values will create. By contrast this society would evidence concern for others, law and order, justice, fairness, honesty, integrity, openness, courage, a preparedness to take risks for fair rewards, enterprise, invention, intelligence, thoughtfulness, freedom, good sense, concern, knowledge, underlying convictions, mature restraint, self-confidence, loyalty, responsibility for others, self-respect, pride, vision, vibrancy, patriotism, inspiration and interest. Above all, a willingness to support one's country, the best for oneself and one's family. An optimism, a sense of fulfillment, a desire to reach maturity so that one is at peace with oneself and the world, and in a natural state of grace.

28

28

A natural state of grace

. Clear enough?

. Clear enough?

This passage comes from the draft of a critical document, the 1977 “Stepping Stones” report, written by the future head of her policy unit, John Hoskyns. “Stepping Stones” was the blueprint for the Thatcher Revolution.

In 1977, Hoskyns collaborated with Thatcher's adviser Norman Strauss on a plan for the Tory Party's communication strategy. Hoskyns sent Thatcher the following memorandum summarizing their recommendations:

The objective is to persuade the electorate that they must consciously and finally reject socialism at the next election . . . Before voters will do this they must feel:

a) A deep moral disgust with the Labour-Trades Union alliance and its resultsâthe “sick society.” (Disappointment with the material results is not enough.)

b) A strong desire for something betterâthe “healthy society.” (The hope of better material results is not enough.)

29

29

To this end, the author advises, Thatcher's speeches should

Show how the Labour-Trades Union alliance “power at any price” has corrupted the union movement and impoverished and polluted British society.

30

30

Later, in a review of the “Stepping Stones” plan, he notes:

Relative decline makes little impact on ordinary people until it has gone so far that it is almost too late . . . We therefore suggested that the key to changing attitudes would be people's emotional feelings, especially anger or disgust at socialism and union behavior.

31

31

Note again: The point is not that socialism has made people worse off, materially. It is that Britain is corrupt, immoral, disgusting, and polluted. It must be returned to a state of grace. This is a much more ambitious program, and there is no doubt that it was, indeed, Thatcher's program.

Nothing less.

“Stepping Stones” is an essential artifact, the document that best expresses a core precept of Thatcherism: British decline was a punishment for the sin of socialism. Conservative policy was developed around the strategy set out by Hoskyns in this paper,

which not only helped Thatcher achieve victory, but led directly to almost every key Thatcherite reform.

which not only helped Thatcher achieve victory, but led directly to almost every key Thatcherite reform.

Thatcher's inner circle was famously divided between the wets and the dries. The wets resisted the radicalism of her program. The dries were true believers. Hoskyns was drier than a Churchill martini; indeed, he resigned from government service in 1982, exasperated, having decided that Thatcher herself was a bit damp.

Hoskyns joined the military at the age of seventeen, one week after VE day, and served in the army for a decade, helping to quell the Mau Mau rebellion. He went on to be an extremely successful software entrepreneur. Like many of the men close to Thatcher, he was an outsider; not only was he not educated at Oxford or Cambridge, he did not have a university education at all.

At the time Thatcher came to power, very few prominent figures in government had any kind of background in business. Many still don't. “You get a tendency to think,” Hoskyns says to me over lunch, “that âbusiness is a sort of unskilled labor for people who aren't as clever as I am,' you know, âI got a First in PPE and therefore I'm naturally going to be in the cabinet, and I'm going to be running the world, even though I've never

done

anything.' I mean, David Cameron is a classic example of this.”

32

It maddened Hoskyns that the men determining British economic policy had no idea what managers and entrepreneurs actually

did,

what it really took, day by day, to create wealth.

done

anything.' I mean, David Cameron is a classic example of this.”

32

It maddened Hoskyns that the men determining British economic policy had no idea what managers and entrepreneurs actually

did,

what it really took, day by day, to create wealth.

Parenthetically, Bernard Ingham's reaction when I described Hoskyns's views was priceless:

CB:

He was extremely critical of the civil service, and felt that it was stacked by people who knew nothing about business, nothing about economics, had no experience of running a

company, and felt this was one of the great liabilities that Thatcher confrontedâwhat do you say to that?

He was extremely critical of the civil service, and felt that it was stacked by people who knew nothing about business, nothing about economics, had no experience of running a

company, and felt this was one of the great liabilities that Thatcher confrontedâwhat do you say to that?

BI:

It is in my view a load of

bunkum!

They aren't there to run a business, they're there to run the government machine! That's rather like the press telling me that the government didn't know anything, and this sort of thing, and I said, “You

dare

!” I mean, I

exploded

, in a very early encounter, I said, [

shouting and banging table

] “You

dare

to tell me that you know how to run

any

bloody business when you people were playing Mickey Mouse on a Friday night on Fleet Street!” I mean, people made up identities in order that they could be paid! I said, “

Get stuffed!

” I said.

“Go away

!” I mean, I got

so

angry with them. [

Calming down slightly

] But

no

, I don't think you have to be a businessman to know how to run Britain, especially in those days, when businessmen had made a complete

hash

of managing their businesses. They couldn't manage them without the government! I mean, the number of times that I wasâI justâI was reduced to

groaning

, quietly, in meetings, when these

businessmen

came in, stormed upon her, said what a

brilliant

Prime Minister she was, but we need more incentives! And I

cheered

when she said, “You realize that âincentives' means more taxation, do you?” I mean, they were

totally

insecure,

totally

insecure in their ideology, and they were

pure

opportunists! . . . In any case, how many businessmen have got

any

experience in government?

Bah

! . . .

Maybe

life is a bit more

complicated

than

Mr. Hoskyns

thinks!

It is in my view a load of

bunkum!

They aren't there to run a business, they're there to run the government machine! That's rather like the press telling me that the government didn't know anything, and this sort of thing, and I said, “You

dare

!” I mean, I

exploded

, in a very early encounter, I said, [

shouting and banging table

] “You

dare

to tell me that you know how to run

any

bloody business when you people were playing Mickey Mouse on a Friday night on Fleet Street!” I mean, people made up identities in order that they could be paid! I said, “

Get stuffed!

” I said.

“Go away

!” I mean, I got

so

angry with them. [

Calming down slightly

] But

no

, I don't think you have to be a businessman to know how to run Britain, especially in those days, when businessmen had made a complete

hash

of managing their businesses. They couldn't manage them without the government! I mean, the number of times that I wasâI justâI was reduced to

groaning

, quietly, in meetings, when these

businessmen

came in, stormed upon her, said what a

brilliant

Prime Minister she was, but we need more incentives! And I

cheered

when she said, “You realize that âincentives' means more taxation, do you?” I mean, they were

totally

insecure,

totally

insecure in their ideology, and they were

pure

opportunists! . . . In any case, how many businessmen have got

any

experience in government?

Bah

! . . .

Maybe

life is a bit more

complicated

than

Mr. Hoskyns

thinks!

Back to Hoskyns, who in fairness would actually be described as the Thatcherite who

best

appreciated the complexity of life. In the 1970s, contemplating the intensely hostile business environment in which he was obliged to operate, he began thinking obsessively about the etiology and dimensions of the British sickness. “It was,” he writes, “like one of those puzzles from a Christmas cracker that

you can neither solve nor leave alone.”

33

His analysis of this sickness, which he details in his memoirs, is one of the most comprehensive extant.

best

appreciated the complexity of life. In the 1970s, contemplating the intensely hostile business environment in which he was obliged to operate, he began thinking obsessively about the etiology and dimensions of the British sickness. “It was,” he writes, “like one of those puzzles from a Christmas cracker that

you can neither solve nor leave alone.”

33

His analysis of this sickness, which he details in his memoirs, is one of the most comprehensive extant.

One could start the discussion at almost any point: trade union obstruction, inflationary expectations, the tendency of the best talent to keep away from the manufacturing industry, fiscal distortions, high interest rates, an overvalued pound, stop-go economic management, the low status of engineers, poor industrial design, the anti-enterprise culture, illiterate teenagers . . . Almost everything turned out to be a precondition for almost everything else, and trying to solve one problem in isolation would probably make the other problems more intractable.

34

34

Other books

A Gathering of Widowmakers (The Widowmaker #4) by Mike Resnick

The Phoenix War by Richard L. Sanders

Como detectar mentiras en los niños by Paul Ekman

The Billionaire's Impulsive Lover (The Sisterhood) by Elizabeth Lennox

Miedo y asco en Las Vegas by Hunter S. Thompson

Book of Shadows by Cate Tiernan

Prairie Fire by Catherine Palmer

Death by Diamonds by Annette Blair

Bitten in Two by Jennifer Rardin