The World of Caffeine (38 page)

Read The World of Caffeine Online

Authors: Bonnie K. Bealer Bennett Alan Weinberg

Misinformation about caffeine abounds today, even as it did in the days of Simon Pauli and Buntekuh. Herbal remedy sales representatives take advantage of a generalized concern about caffeine to help push “alternative” products, for which they promise the same or greater benefits. Unfortunately for the unwary, the active ingredient in many of these nostrums is either caffeine or caffeine compounded, potentially dangerously, with ephedrine, which is sometime referred to as “ma-huang,” the Chinese herb from which it is derived. The following ad on the Internet for EXTRA BOOST was particularly amusing because it touts a guarana-based supplement as a medicine to reduce “cravings for caffeine,” a claim which is certainly true, because one of its active ingredients

is

caffeine.

For anyone imagining that EXTRA BOOST is a magical new remedy, the letdown comes quickly, as soon as the two active ingredients are described:

Guarana:

This is a plant that grows in the northern and western portions of Brazil. Reportedly, its seeds have been used for centuries by the natives of the Amazon for added energy and mental alertness.

Mahuang:

Imported from China, this plant, according to the Chinese, reduces the desire for food, metabolizes fat, increases energy and mental alertness.

Another ad, this time for guarana capsules, is more accurate, declaring, “Guarana is a caffeine-rich extract that, in addition to 2–3 times the caffeine found in coffee, also contains xanthine compounds such as theobromine and theophylline. Made into a popular Brazilian cola drink, guarana is consumed for energy and stimulation. Guarana has also been used traditionally as an anti-diuretic, a nerve tonic, to reduce hunger, and to relieve headaches, migraines and PMS symptoms.”

A cybercafé is a coffeehouse in cyberspace. That is, it is a coffeehouse without a house and without coffee. So in what sense is it a coffeehouse at all? In the sense that the coffeehouse serves as a universal symbol for a forum in which friendly strangers, often gathered from the fringes of society, can convene to discuss art, politics, science, or almost any other subject matter. That is what the coffeehouse was in the lands of its inception, the cities, villages, and travelers’ inns of the Middle East in the sixteenth century. That is what it was in England in the seventeenth century, in Greenwich Village in the 1950s, in Seattle in the 1980s, and that is what it is in cyberspace as we enter the third millennium. At the traditional coffeehouse people sit at little tables, sip coffee, read the news, and meet and talk face to face. At the cybercafé, there are little monitors and keyboards, at which people sit, sip coffee, search the web and chat with people around the world. Thus the cybercafé carries forward the tradition of coffee-house conversation into the twenty-first century.

The notion of the “extended café” that the cybercafé embodies is not as unprecedented as it may appear at first. Since at least the nineteenth century, the word “café,” which simply means “coffee” in French, has been used worldwide to designate establishments that serve alcohol or absinthe and light food, occasionally featuring musical performers, and only incidentally serving coffee. It also designates a small, plain or fancy, informal restaurant. For whatever reasons, the word “coffee” has come to signify public places for gathering to drink, talk, eat, or be entertained. Rather than diminishing our estimate of caffeine’s importance, this linguistic generalization suggests that caffeine’s social significance is both deep and broad.

What do a design studio in Atlanta, a poetry magazine in San Francisco, a software module for Apple computers, and a new multiplayer Internet game have in common? They all go by the name “caffeine.” Suddenly

caffeine,

not just its vehicles coffee and tea, is on everyone’s tongue. A network magazine supporting proprietary online services recently issued a list of the

Best of the Web. One category, including about a dozen sites, most of which feature high-tech products, was “Coffee and Caffeine.” A Canadian food information bureau uses the acronym CAFFEINE for its home page. Another example of its acronymic use is Computer Aided Fast Fabrication Exploration in Engineering, an Internet site hailing from Berkeley.

Perhaps it is because of the profile of caffeine’s cognitive effects, its power to increase alertness, speed, diligence, and retention, especially in repetitive tasks, that computer people are among the leading caffeine consumers in America. Or perhaps it’s just that they get weary from long hours writing and using software. Whatever the reason, the link between computer work and caffeine is pretty much taken for granted as a fact of popular culture. For example, in a 1996 news article, “What computer users really want in a keyboard,” Joe Fasbinder, a UPI reporter, describes a computer keyboard with a special feature aimed at caffeine users: “if you spill any ‘computer-programmer’ fluids (i.e., anything with caffeine in it), you can simply keep typing, or take the thing to the kitchen sink, run some water over it and let it dry out.”

In the roiling seas of the Internet it’s difficult for one person to make a big splash. One man who is trying is Shannon Wheeler. He has dedicated himself to creating and disseminating comic books, T-shirts, and other pop culture paraphernalia celebrating the culture of caffeine and the adventures of a character with a large coffee cup permanently affixed to the top of his head, called simply the “Too Much Coffee Man.” Another Internet caffeine promoter, Robert Therrien, or BADBOB, as he calls himself, is a former student at Antioch, a caffeine aficionado, Internet maven, cartoonist, and something of a versifier. In his cartoons he cries out with existential angst over the cognitive, emotional, and social dissonances that ripple outward from the caffeine habitué.

11

An effort to use caffeine to promote products is found in a 1995

Working Woman

article on new skin creams.

12

The article features information on Clinique’s Moisture On-Call, ($30/1.7 oz), a product that, according to Shirley Weinstein, Clinique’s vice president of product development, “uses caffeine to catalyze the production of lipids, substances that keep the skin moist and unlined, at the basal-cell layer. Results begin to show in about a month, the amount of time it takes cells to move from the bottom of the epidermis to its surface.” Weinstein referred our inquiries to the company’s public relations department, which left us a message to the effect that Clinique did not “participate in books.” And so we have no information about how caffeine gets the lipid-producing juices flowing.

A news story from China illustrates how caffeine there is placed in the same category as the West places dangerous narcotics. It was reported by the Heilongjiang

Daily,

dateline Beijing, March 29, 1995, that police in northern China arrested a ring of seventeen caffeine dealers who were attempting to close a deal to sell a large quantity of caffeine pills. Like opium and other psychoactive drugs, caffeine is a controlled substance in China. Police seized 85 pounds of caffeine and more than one million caffeine pills, with a reputed street value of several hundred thousand dollars. The ring had illegally diverted the caffeine from a pharmaceutical shipment en route from Beijing.

13

In the 1960s, the days of acid rock, songs such as “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” and “Spoonful” celebrated drugs such as LSD and cocaine. In the more timid culture of the 1990s, caffeine has become a drug noticed and venerated by the young. There have been several recent songs about the mind- and body-altering power of caffeine in coffee. We have also noticed an increase in the word “caffeine” figuring into phrases, such as “he needs a shot of caffeine,” that formerly referenced other drugs such as adrenaline.

An Internet thread in the alt.drugs.caffeine newsgroup began with a message to the effect that a handful of chocolate-covered coffee beans, which are “SO easy to just sit and munch,” release as much caffeine when eaten as you get from drinking a cup of coffee, so it is wise to be careful and not eat the whole bag. In response a member of a rock band called Cathead reminisced about some uses of whole beans backstage before concerts:

Before every show (back in the good old days) we would share a bag (i.e. You know the bags they offer in the bulk section of Safeway?) of espresso beans. I can only say that each show back then was really intense…every time.

14

Is the coffee and tea party really nearly over? Some people, evidently disgusted with the caffeine craze sweeping the world at the turn of the millennium, have lined up to prophesy the end of the excitement. Several books have appeared in the last few years cautioning people about the supposed dangers of caffeine consumption. One of their number is

Caffeine Blues: Wake up

to the Hidden Dangers of America’s #1 Drug,

by Stephen A.Cherniske (Warner Books, 1998). The publisher states that this book, which presents a daunting panoply of dire warnings about caffeine reminiscent of Simon Pauli, “exposes the harmful side effects of caffeine and gives readers a step-by-step program to reduce intake, boost energy, create a new vibrant life and recognize the dangers.” Another is

Danger: Caffeine,

by Patra M.Sevastiade (Rosen Publishing Group, 1998), a book intended for children five to nine that “explains how caffeine affects the body and the harm overuse of it can cause.” Still another is

Addiction-Free

—

Naturally: Liberating Yourself from Tobacco, Caffeine, Sugar, Alcohol, Prescription Drugs,

Cocaine, and Narcotics,

by Brigette Mars (Inner Traditions International, 2000), which, as the title makes obvious, puts caffeine in some pretty nasty company. A more unusual contribution to cautionary caffeine literature is

Brief Epidemiology of

Crime: With Particular Reference to the Relationship between Caffeine and Alcohol Use and Crime,

by Peter D.Hay (Peter D.Hay, 1999).

Cartoons by Robert Thierrien, Jr., a.k.a. BADBOB. These energetic images, among a series by the artist celebrating caffeine’s place in contemporary culture, have been widely reproduced on T-shirts and coffee mugs. (By permission of the artist)

Organizations have arisen to help people avoid what their members regard as the evils of caffeine. Among them are Caffeine Anonymous, a twelve-step program of caffeine addicts who gather weekly at a church to support each other’s efforts to quit. More radical are the efforts of Caffeine Prevention Plus, a nonprofit organization “dedicated to caffeine and coffee prevention.” A consultant for this redoubtable group recently wrote an article advocating that coffee be made an illegal substance because of the harm it poses for coffee drinkers and society. In his scientismic polemic to outlaw caffeine, he explains that the putative therapeutic benefits of caffeine are figments of the “coffee lobby” and that there are other compounds available to do anything caffeine can do and do it better. In addition, according to this group, caffeine is solely

responsible for more than 25 percent of British bad business decisions, including the Barings bank disaster, and is believed to be involved in aggravating more than 50 percent of all marital disputes in the United States.

the natural history of caffeine

caffeine in the laboratory

After the fall of Rome, the sciences originated by the Greeks lay quiescent for more than a millennium, eventually falling under the spell of such alchemical adepts as Albertus Magnus (1193–1280) and Philippus Aureolus Paracelsus (1490–1541). These sciences were quickened in Restoration England by the members of one of the oldest and most important coffee klatches in history, the Royal Society. Still one of the leading scientific societies in the world, the Royal Society began in 1655 as the Oxford Coffee Club, an informal confraternity of scientists and students who, as we said earlier, convened in the house of Arthur Tillyard after prevailing upon him to prepare and serve the novel and exotic drink. To appreciate the audaciousness of the club members, we must remember that coffee was then regarded as a strange and powerful drug from a remote land, unlike anything that had ever been seen in England. It was not, at first, enjoyed for its taste, as it was brewed in a way that most found bitter, murky, and unpleasant, but was consumed exclusively for its stimulating and medicinal properties. The members of the Oxford Coffee Club took their coffee tippling to London sometime before 1662, the year they were granted a charter by Charles II as the Royal Society of London for the Improvement of Natural Knowledge.

Historical reflection on changing fashions in drug use might justify the saying, “By their drugs you shall know them.” Members of the Sons of Hermes, the leading alchemical society of the Middle Ages, experimented with plants and herbs, almost certainly including the Solanaceæ family, commonly known as nightshades, which comprises thorn apple, belladonna, madragrora, and henbane.

1

These plants contain the hallucinogenics atropine, scopolamine, and hyoscyamine, which were used historically as intoxicants and poisons and more recently as “truth serums.” These drugs often produce visions, characteristically inducing three-dimensional psychotic delusions, often populated with vividly real people, fabulous animals, or otherworldly beings. Because of atropine’s ability to bring about a transporting delirium, witches rubbed an atropine-laced ointment into their skin to induce visions of flying. Obviously, the Solanaceæ drugs are as well-suited to the fabulous, symbolic, magical, transformational doctrines of alchemy as caffeine is to the rational, verifiable, sensibly grounded, and literal endeavors of modern science.

It may therefore not be entirely adventitious that the thousand-year lapse of European science in the Middle Ages, during which naturalism commingled promiscuously with magic, ended at the same time that the first coffeehouses opened in England and that coffee, fresh from the Near East, became suddenly popular with the intellectual and social avant-garde in Oxford and London. The aristocratic Anglo-Irish Robert Boyle (1627–91), the father of modern chemistry, regarded in his time as the leading scientist in England, was a founding member of the original Oxford Coffee Club. Credited with drawing the first clear line between alchemy and chemistry, Boyle formulated the precursor to the modern theory of the elements, achieving the first significant advance in chemical theory in more than two thousand years.

2

Within a few years after the English craze for caffeine began, the modern revolutions, not only in chemistry, but in physics and mathematics as well, were well under way. Twentieth-century scientific studies suggest that caffeine can increase vigilance, improve performance, especially of repetitive or boring tasks such as laboratory research, and increase stamina for both mental and physical work. In consequence of its avid use by the most creative scientists of the second half of the seventeenth century, caffeine may well have expedited the inauguration of both modern chemistry and physics and, in this sense, have been the only drug in history with some responsibility for stimulating the formulation of the theoretical foundations of its own discovery.

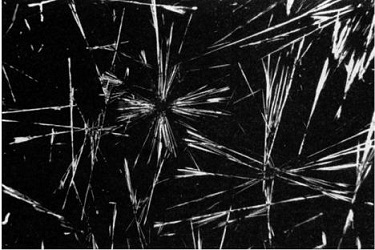

Caffeine is a chemical compound built of four of the most common elements on earth: carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and oxygen. The pure chemical compound is collected as a residue of coffee decaffeination, recovered from waste tea leaves, produced by methylating the organic compounds theophylline or theobromine, or synthesized from dimethylurea and malonic acid. At room temperature, caffeine, odorless and slightly bitter, consists of a white, fleecy powder resembling cornstarch or of long, flexible, silky, prismatic crystals. It is moderately soluble in water at body temperature and freely soluble in hot water. Caffeine will not melt; like dry ice, it sublimes, passing directly from a solid to a gaseous state, at a temperature of 458 degrees Fahrenheit.

3

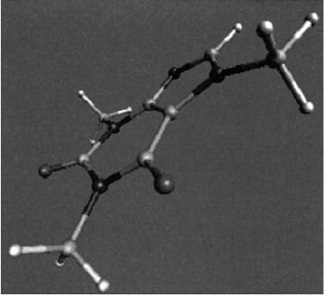

A computer-generated model of the caffeine molecule.

The formula for caffeine is C

8

H

10

N

4

O

2

, which means that each caffeine molecule comprises eight atoms of carbon, ten atoms of hydrogen, four atoms of nitrogen, and two atoms of oxygen. However, to understand the structure and properties of caffeine, or of any chemical compound, it is necessary not only to identify its atomic constituents but also to describe the way in which these constituents fit together. A compound’s chemical name articulates this chemical structure and serves to designate how its parts are arranged and connected. Caffeine has several chemical names, or alternative ways of representing its structure, the most common of which is 1,3,7-trimethylxanthine. The name revealing its structure most fully is 1H-Purine-2,6-dione, 3,7-dihydro-1,3,7-trimethyl. Other chemical designations for caffeine include:

1,3,7-Trimethyl-2, 6-dioxopurine

7-Methyltheophylline

Methyltheobromine

To understand the way in which these names represent caffeine’s structure, it is helpful to consider them in the context of the structural descriptions of caffeine’s parent compound, purine, and of caffeine’s isomers, or close relations.

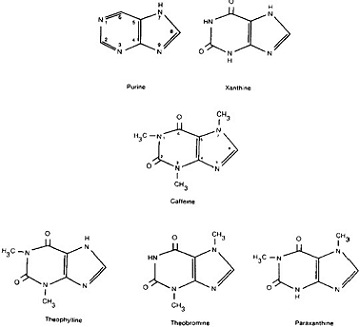

Caffeine is one of a group of purine alkaloids, sometimes called methylated xanthines, or simply, xanthines. Other methylated xanthines include theophylline, theobromine, and paraxanthine. All three are congeners, or chemical variations, of caffeine, and all three are primary products of caffeine metabolism in human beings. Purine itself is an organic molecule composed entirely of hydrogen and nitrogen. All purine bases, including caffeine, are nitrogenous compounds with two rings in the molecules, five- and six-membered, each including two nitrogen atoms. The purine alkaloid xanthine is created when two oxygen atoms are added to purine.

The other purine alkaloids, in turn, are built out of xanthine by adding methyl groups, that is, groups of one carbon and three hydrogen atoms, in varying numbers and positions. For example, caffeine, a trimethylxanthine, the most common methylxanthine in nature, is xanthine with three added methyl groups, in the first, third, and seventh positions. Similarly, theophylline (1,3-dimethylxanthine) consists of xanthine with methyl groups in the first and third positions, theobromine (3,7-dimethylxan-thine), consists of xanthine with methyl groups in the third and seventh positions, and paraxanthine (1,7-dimethylxanthine) consists of xanthine with methyl groups in the first and seventh positions. Because the body transforms caffeine into each of these isomers, they may well play a part in caffeine’s health effects.

Although purine itself does not occur in the human body, chemicals in the purine family are widely present there as throughout nature. In fact, in addition to being the parent compound of caffeine and other methylxanthines, purine is the parent compound of adenine and guanine, two of the four basic constituents of the nucleotides that form RNA and DNA, the molecular chains within the cells of every living organism that determine its genetic identity. Some scientists have speculated that, because of this similarity to genetic material, caffeine and its metabolites may introduce errors into cell reproduction, causing cancer, tumors, and birth defects. As of this writing, there is no credible evidence to substantiate such fears.

The molecular structure of caffeine and related compounds.

Because caffeine is fat soluble and passes easily through all cell membranes, it is quickly and completely absorbed from the stomach and intestines into the blood-stream, which carries it to all the organs. This means that, soon after you finish your cup of coffee or tea, caffeine will be present in virtually every cell of your body. Caffeine’s permeability results in an evenness of distribution that is exceptional as compared with most other pharmacological agents; because the human body presents no significant physiological barrier to hinder its passage through tissue, the concentrations attained by caffeine are virtually the same in blood, saliva, and even breast milk and semen.

Caffeine’s stimulating effects largely depend on its power to infiltrate the central nervous system. This infiltration can only be accomplished by crossing the blood-brain barrier, a defensive mechanism that protects the central nervous system from biological or chemical exposure by preventing large molecules, such as viruses, from entering the brain or its surrounding fluid. Even following intravenous injection, many drugs fail to penetrate this barrier to reach the central nervous system, while others enter it much less rapidly than they enter other tissues. One of the secrets of caffeine’s power is that caffeine passes through this blood-brain barrier as if it did not exist.

Photomicrographs of caffeine crystals at a magnification of 28x. (Photograph taken by Paul Barrow at BioMedical Communications, University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, © 1999 Bennett Alan Weinberg and Bonnie K.Bealer.)

The maximum concentrations of caffeine in the body, including in the blood circulating in the brain that is responsible for caffeine’s major stimulating effects, is typically attained within an hour after consumption of a cup of coffee or tea. Absorption is somewhat slower for caffeine imbibed in soft drinks. It is important to remember that the concentration of caffeine in any person’s body is a function not only of the amount of caffeine consumed but of the person’s body weight. After drinking a cup of coffee with a typical 100 mg of caffeine, a 200-pound man would attain a concentration of about 1 mg per kilogram of body weight. A 100-pound woman would attain about 2 mg per kilogram and would therefore (all other metabolic factors being considered equal) experience double the effects experienced by the man.

What becomes of all this ambient caffeine permeating your cells?

Factors Affecting Rate of Caffeine Metabolism in Humans

| Slows Metabolism | Speeds Metabolism |

| alcohol | cigarettes |

| Asian | Caucasian * |

| man | woman |

| newborn | child |

| oral contraceptives | |

| liver damage | |

| pregnancy |