The World of Caffeine (34 page)

Read The World of Caffeine Online

Authors: Bonnie K. Bealer Bennett Alan Weinberg

The coffeehouse tradition of troubadour and balladeer, which began in the Middle East in the early sixteenth century, continued in the English coffeehouses of the Restoration (when these establishments became “the usual meeting-places of the roving cavaliers, who seldom visited home but to sleep”),

4

and was impressively revived in twentieth-century America, first by the nonconformist Beat Generation of the 1950s and then by the folk and flower child social rebels of the 1960s. The Beat Generation movement began in San Francisco’s North Beach, Los Angeles’ Venice West, and New York’s Greenwich Village. Its members affected an exhausted sophistication and demoralized bohemian irony that put them in the company of a certain tradition of coffeehouse denizens. The apolitical Beat Generation take on café culture is represented by Beat poets Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Allen Ginsberg, who read their works at coffeehouses such as the Coexistence Bagel Shop in San Francisco and emphasized personal fulfillment through self-expression, nonconformity, free love, and the use of drugs and alcohol. Their more socially minded but more drug-dependent hippie successors are represented by folk singers such as Bob Dylan, who began performing professionally in the coffeehouses of Greenwich Village, where he sang Woody Guthrie’s Depression-era songs and others of his own composition to a young audience that had ridden into adulthood on an unprecedented wave of prosperity that had not yet crested. Dylan’s works, and those of his fellow singer-composers, such as Joan Baez and Phil Ochs, helped shape the music of a generation and embodied the social values of the civil rights and anti-Vietnam War movements.

What are we to make of the coffeehouse renaissance of the 1990s? Certainly it is no flash in the pan. New York real estate prices have seemed high for generations, but they have recently been driven still higher by the competition for space among a new generation of coffeehouse and café proprietors. Many of the new establishments are the progeny of the chain behemoths, such as Starbucks, Timothy’s, and Brothers Gourmet Coffee, each of which boasts many new outlets in Manhattan. Others, like Coopers Coffee and New World Coffee, are the offspring of smaller ventures hoping to expand to compete with their bigger rivals. Bookstores and department stores are increasingly including cafés under their roofs. Some traditional proprietors are benefiting from the upswing. For decades Chock Full o’ Nuts was the ultimate coffeeshop chain, providing cheap but good cups of coffee and fast sandwiches to busy city workers. After ten years of relying on institutional sales and sales of coffee beans and spices, it is again turning to the development of coffeehouses and cafés.

The caffeinated drinks, coffee and tea, wherever they were first encountered, were invariably regarded as medicines before they came into use as comestibles. Coca-Cola, the first of the caffeinated soft drinks, also began as a patent medicine, and was first sold in the form of a tonic syrup at pharmacies. Before the turn of the century, however, Coca-Cola had become a popular soft drink that encountered public relations problems, first over its still unverified cocaine content and then because of its caffeine. In the decades since, the Coca-Cola Company has distanced itself from any association in the public’s mind with drugs. Cocaine, if it was ever present in more than a negligible quantity, was eliminated. The caffeine content was cut in half. However, caffeine remains to this day the only pharmacologically active ingredient present in beverages that are dispensed from vending machines, soda fountains, and convenience stores.

Coca-Cola and the Wiley Campaign: Wiley as the Kha’ir Beg of the Twentieth Century

Dr. Harvey Washington Wiley (1844–1930), who at the height of his career enjoyed great national celebrity and power, waged a war against Coca-Cola in the early twentieth century that almost wrecked the company. Like Kha’ir Beg in early-sixteenth-century Mecca, Wiley was a governmental official charged with protecting the public welfare. As the first director of the U.S. Bureau of Chemistry, the forerunner of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Wiley found nothing amusing

about the blithe and celebratory indulgence in caffeinated soft drinks that was sweeping the country. Kha’ir Beg had been concerned about social subversion; Wiley was worried about food adulteration and the health of the nation’s children. Each had a large measure of reason on his side.

Wiley saw an essential difference between coffee and tea as caffeinated beverages and Coca-Cola and its imitators. Adults were by far the primary consumers of coffee and tea, and everyone was keenly aware that these drinks contained caffeine. Children, however, were the greatest consumers of Coca-Cola, and most people did not associate the drug with the drink, an association strongly discouraged and underplayed by the company’s brilliant advertising and public relations efforts.

5

The epochal conflict between Wiley and the Coca-Cola Company, one of the nation’s most powerful corporations, epitomizes the issues and players that have featured in the centuries-long struggle between caffeine’s purveyors and detractors. In 1902, after twenty years of leading the U.S. Bureau of Chemistry in a fight against the adulteration of food, Wiley achieved national prominence when he created a “poison squad,” a group of twelve young healthy adult volunteers who would test the safety of additives. He campaigned against the nostrums of the patent medicine industry and became a fervent advocate of the frequently proposed and invariably defeated efforts to enact pure food and drug legislation. In 1906 public sympathies began to change, and the Pure Food and Drugs Act, known then as “Dr. Wiley’s Law,” was finally passed. Wiley wasted no time investigating Coca-Cola as a vehicle of caffeine. Headlines appeared in 1907 reading, “Dr. Wiley Will Take Up Soda Fountain ‘Dope.’” John Candler, who was running Coca-Cola at that time along with his brother Asa, was outraged. Candler could not understand Wiley’s animus, asserting, “There can be no more objection to the consumption of caffeine in the form of Coca-Cola than there is to the importation of tea and coffee and their use.”

6

The company had no sooner overcome the scandalous rumors about cocaine, which had finally been decisively dispelled, than this new problem over caffeine had arisen. It was to prove more difficult to resolve.

Candler and Wiley had similar backgrounds, including fundamentalist upbringings and training in medicine and chemistry, but they took opposite positions on this central issue. Wiley had no quarrel with caffeine as it occurred naturally in coffee or tea. His lifelong campaign was against adulterants, in acknowledgment of which his followers called him “a preacher of purity,” while his detractors dubbed him “a chemical fundamentalist.” It was from this perspective of concern about adulterants or additives that Wiley saw the caffeine question. He regarded the introduction of the drug into soft drinks as pernicious and deceptive and potentially harmful, especially to the children. Wiley’s positions, which he maintained for the rest of his life, are well represented in his speech in favor of coffee, “The Advantages of Coffee as America’s National Beverage,” and the magazine articles from the same period which he used to batter the Coca-Cola Company.

Wiley was caught in a bind. He had tried to initiate seizures of Coca-Cola, but the federal government refused to cooperate, arguing that caffeine had not been proved harmful and that, furthermore, should it be so proved, coffee and tea would have to be banned as well as Coca-Cola. However, Wiley insisted that if parents really understood that their children were using a drug every time they drank a Coke, there would be more sympathy on his side.

The conflict was finally joined in a federal suit, called, in the legal fashion of such things,

The United States vs. Forty

Barrels and Twenty Kegs of Coca-Cola,

which opened in court on March 13, 1911, the second case do so under the new drug laws.

7

The witnesses included religious fundamentalists who argued that the use of Coca Cola led to wild parties and sexual indiscretions by coeds and induced boys to masturbatory wakefulness. But most of the testimony was scientific in nature. Coca-Cola presented an array of expert witnesses with impressive credentials. Unfortunately, by today’s standards, the experiments on which their testimony relied were compromised by inadequate protocols. That is, their conclusions tended to support the prior opinions of the investigators regardless of the data actually gathered.

The one exception was the work of Harry Hollingworth, a young psychology professor at Columbia University, and his wife and research assistant, Leta, who designed and performed the first comprehensive double-blind experiments on the effect of caffeine on human health. These studies are still being cited in journal articles today. For example, a 1989 study published in the

American Journal of Medicine

referenced the Hollingworths’ 150-page 1912 study,

8

to the effect that “a total day’s caffeine dose of 710 mg was necessary to lessen subjective sleep quality.” Their careful work demonstrated that caffeine in modest doses improved motor performance and did not disturb sleep. In sum, their work failed to support Wiley’s concerns; although in fairness it must be added that in large part it also failed to address them in any significant way.

Coverage of the trial was frequently sensationalistic, with one headline reading, “EIGHT COCA-COLAS CONTAIN ENOUGH CAFFEINE TO KILL.”

9

Wiley himself never testified, leading us to speculate that his group of young food tasters had not experienced any harmful consequences from their exposure to the drink. The case was finally decided on technical grounds that have little to do with caffeine and make little sense. The District Court judge Sanford, who later was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court, directed a jury verdict in favor of Coca-Cola, ruling that their drink was not mislabeled, because it did contain minute amounts of both cocaine and cola, and that, furthermore, because caffeine had been part of the original formula or recipe for the beverage, it could not be legally regarded as an additive. Generous in victory, Coca-Cola voluntarily agreed never to feature any child under twelve in their advertisements, a forbearance they relaxed only in 1986.

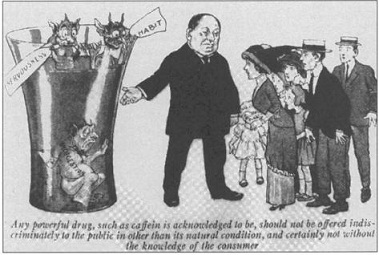

Cartoon of Wiley admonishing an innocent public about the evil goblins lurking unseen in a glass of Coca-Cola. (

Good Housekeeping,

1912)

Wiley did not give up. He used the publicity from the case to try to push through provisions adding caffeine to the federal list of habit-forming and harmful substances that must be named on product labels. Still shy of promoting the presence of caffeine in their products, Coca-Cola successfully fought the amendments.

Meanwhile the government successfully appealed the District Court’s ruling to the Supreme Court. It was now determined that caffeine was an added ingredient after all, and the case was remanded to Judge Sanford for retrial on the issue of caffeine’s safety. This time the case was settled out of court, and Coca-Cola agreed to cut the amount of caffeine in its soft drink by half. In return there was an unwritten accord that the Bureau of Chemistry, by then operating under new leadership, would, from then on, leave Coca-Cola in peace.

Coca-Cola has not relied on that ancient truce to protect its interests from those meddlers, newborn in every generation, who would use the law to control what ostensibly free adult citizens are allowed to eat or drink. In the 1970s, largely as a response to reformational grumblings stirred up by concern over an unsubstantiated link between caffeine and pancreatic cancer, Coca-Cola and other purveyors of dietary caffeine set up and funded the International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI) and its public relations arm, the International Food Information Council (IFIC), both based in Washington, D.C., to help forestall any efforts to regulate or ban caffeine. The heart of these groups was their Caffeine Committee. In the last twenty years ILSI has sponsored and IFIC has publicized dozens of reputable research projects and international conferences of scientists to evaluate the role of caffeine in human health. Naturally, the Caffeine Committee is careful to search out and support those researchers who see caffeine as a relatively harmless compound and to avoid supporting those who would like to see it removed from the market. Nevertheless, the ILSI studies are good scientific efforts, and their results have made important contributions to the inadequate understanding of caffeine’s pharmacological effects.

“Caffeine is caffeine,” the logician might observe, bringing to bear the powerful insight of sovereign reason. Yet with respect to caffeine, coffee and tea, its major natural sources, differ in at least one important way from caffeinated colas and other caffeinated soft drinks, to which caffeine has been added: Coffee and tea are primarily the drinks of adults, while soft drinks, as Wiley admonished, are as commonly or more commonly consumed by children, even small children.