The World of Caffeine

Read The World of Caffeine Online

Authors: Bonnie K. Bealer Bennett Alan Weinberg

caffeine

“An amazing book…a challenging mix of history, science, medicine, anthropology, sociology, and popular music, then add a dash of humor, a pinch of polemic, and a dollop of healthful skepticism…. Briskly written, full-bodied, and flavorful.”

–

Kirkus Reviews

“With chapters devoted to the history, science, and cultural significance of coffee, tea, and caffeinated soft drinks,

The

World of Caffeine

reveals a great deal of surprising information about the chemical that we all take for granted.”

–

Wired Magazine

“This book holds everything we ever wanted to know…about the drug that helps many of us keep up with the fast pace of our lives.”

–

Boston Herald,

Editor’s Choice

“Here at last is a lavishly produced history of the world’s favourite mood enhancer, from Mayan chocolate to the Japanese tea ceremony.”

–

London Guardian

“With impressive felicity, Weinberg and Bealer marshal the forces of history, chemistry, medicine, cultural anthropology, psychology, philosophy and even a little religion to tell caffeine’s complicated story…. Fascinating, generously illustrated volume.”

–

Cleveland Plain Dealer

“The scholarship is impressive…. The text is rich with information, yet is easy and pleasant to read.”

–Dr. Peter B.Dews in the

New England Journal of Medicine

“Caffeine shows no signs of surrendering its sovereign position in the hierarchy of humanity’s drugs of choice and I know of no other book that better explains how and why it got there….”

–

New Scientist

“Well-researched and entertaining…contains a wealth of fascinating cultural anecdotes, historical information, and scientific facts which provide a unique perspective on the world’s most commonly used mood-altering drug.”

–Dr. Roland R.Griffiths, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

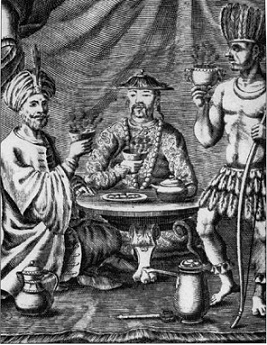

Frontispiece from Dufour’s

Traitez Nouveux & curieux Du Café, Du Thé, et Du Chocolate.

This French engraving, frontispiece for Dufour’s famous 1685 work on coffee, tea, and chocolate, depicts a fanciful gathering of a Turk, a Chinese, and an Aztec inside a tent, each raising a bowl or goblet filled with the steaming caffeinated beverage native to his homeland. On the floor to the left is the

ibrik,

or Turkish coffeepot, on the table at center the Chinese tea pot, and on the floor to the right the long-handled South American chocolate pot, together with the moliné, or stirring rod, used to beat up the coveted froth. Baker, writing in 1891, commented that this image demonstrates “how intimate the association of these beverages was regarded to be even two centuries ago.” It is evident from the conjunction of subjects in the engraving that, long before anyone knew of the existence of caffeine, Europeans suspected that some unidentified factor united the exotic coffee, tea, and cacao plants, despite their dissimilar features and diverse provenances. (The Library Company of Philadelphia)

caffeine

The Science and Culture of the World’s Most Popular Drug

BENNETT ALAN WEINBERG

BONNIE K.BEALER

ROUTLEDGE

New York and London

Published in 2002 by

Routledge

29 West 35th Street

New York, NY 10001

Published in Great Britain by

Routledge

11 New Fetter Lane

London EC4P 4EE

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group.

This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005.

“To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s

collection of thousands of eBooks please go to

www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk

.”

Copyright © 2001 by Bennett Alan Weinberg and Bonnie K.Bealer

Design and typography: Jack Donner

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Any omissions or oversights in the acknowledgments section of this volume are purely unintentional.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Weinberg, Bennett Alan.

The world of caffeine: the science and culture of the world’s most popular drug/

Bennett Alan Weinberg and Bonnie K.Bealer.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-415-92722-6 (hbk.)—0-415-92723-4 (pbk.)

1. Caffeine. I. Bealer, Bonnie K. II. Title.

QP801.C24 W45 2001

613.8’4–dc21 00–059243

ISBN 0-203-01179-1 Master e-book ISBN

eISBN: 978-1-13595-817-6

Bennett Alan Weinberg

dedicates his efforts on this book to his parents,

Herbert Weinberg, M.D., and Martha Ring Weinberg,

who made so much possible for him.

Bonnie K.Bealer

dedicates her efforts to Ms. P.H.,

who knows who she is.

Argument

Health and history seen

Through the crystal caffeine

The authors acknowledge with thanks the research assistance of the staff of the Library Company of Philadelphia; the staffs of the Free Library of Philadelphia and the New York Public Library; the staff of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Rights and Reproductions Department; Lynn Farington and John Pollack, librarians of the University of Pennsylvania Rare Book Collections; Charles Kline, director of the University of Pennsylvania Photo Archives; Charles Griefenstein, Historical Reference Librarian at Philadelphia’s College of Physicians; Ted Lingle, then director of the Specialty Coffee Association of America; and Paul Barrow, photographer at the Bio-medical Imaging Center of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine.

We also thank Thomas Meinl of Julius Meinl, A.G., for generously supplying photographs, posters, and especially for providing us a transparency of and permission to reproduce the painting

Kolschitzky’s Café,

which hangs in the boardroom of Julius Meinl, A.G.

Three books deserve special mention as rich sources for our text:

Coffee and Coffee-houses,

by Richard Hattox; above all,

All about Coffee

and

All about Tea,

by William H. Ukers, merchant and scholar, whose masterworks have been drawn upon extensively for information and illustrations by nearly every book on coffee and tea written in the seventy years since their publication.

Our warmest thanks extend to Professor Roland R.Grifftths, Professor of Behavioral Biology and Neuroscience, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, who encouraged our work from the beginning, advised us throughout its early development, and performed a professional and meticulous review of the medical and scientific portions of our manuscript in its early stage for which we are very grateful.

And, of course, we thank our editor, Paula Manzanero, who saw merit in our book and applied her talents and experience to win acceptance for it at Routledge and who, together with our copy editor, Norma McLemore, and our proofreader, Roland Ottewell, contributed the insight and diligence that turned our sometimes rough manuscript into a finished text of which we are proud. For our cover, which is itself a work of art, we thank Jonathan Herder, art director for Routledge. For the book design and typography, we thank Jack Donner. And for putting the many pieces together and graciously accommodating our last-minute emendations, we thank Liana Fredley.

Finally, we warmly acknowledge the help of Antony Francis Patrick Vickery, our dear friend, who saved the book many times when the text seemed about to disappear beneath the rough seas of computer problems, patiently and generously devoting exigent efforts to keep our project afloat, providing advice on content and style, and extending moral and material support without which this book might never have been completed.

Caffeine Encounters

The Turks have a drink called Coffee (for they use no wine), so named of a berry as black as soot, and as bitter, (like that black drink which was in use amongst the Lacedaemonians, and perhaps the same), which they sip still off, and sup as warm as they can suffer; they spend much time in those Coffee-houses, which are somewhat like our Ale-houses or Taverns, and there they sit chatting and drinking to drive away the time, and to be merry together, because they find by experience that kind of drink so used helpeth digestion, and procureth alacrity.

—Robert Burton, “Medicines,”

Anatomy of Melancholy,

2d ed., 1632

Tea began as a medicine and grew into a beverage. In China, in the eighth century, it entered the realm of poetry as one of the polite amusements. The fifteenth century saw Japan ennoble it into a religion of aestheticism, teaism, a cult founded on the adoration of the beautiful among the sordid facts of everyday existence. It inculcates purity and harmony, the mystery of mutual charity, the romanticism of the social order.... It expresses conjointly with ethics and religion our whole point of view about man and nature.

—Kakuzo Okakura,

The Book of Tea,

1906

Caffeine Chem. [ad F. caféine, f. café, coffee+ine] A vegetable alkaloid crystallizing in white silky needles, found in the leaves and seeds of the coffee and tea plants, the leaves of guarana, maté, etc.

—

Oxford English Dictionary,

1971

Caffeine, by any measure, is the world’s most popular drug, easily surpassing nicotine and alcohol. Caffeine is the only addictive psychoactive substance that has overcome resistance and disapproval around the world to the extent that it is freely available almost everywhere, unregulated, sold without license, offered over the counter in tablet and capsule form, and even added to beverages intended for children. More than 85 percent of Americans use significant amounts of caffeine on a daily basis; yet despite that, and despite the fact that caffeine may be the most widely studied drug in history, very few of us know much about it.

This book is not about drug addiction, the preparation of gourmet beverages, botany, psychology, religion, social classes, international trade, or love, art, or beauty. But, in telling the story of the natural and cultural history of caffeine, it necessarily encompasses all of these topics and many aspects of the human condition. We fully consider the health effects of caffeine and also present an engaging tour of the fascinating cultural history of the drug that, through the agency of some of their favorite beverages, has captivated men and women, young and old, rich and poor, conventional and bohemian in virtually every society on earth.

Coffee, tea, and cola are the three most popular drinks in the world. They taste and smell different, but all contain significant amounts of caffeine. From the staggering demand for these drinks, it is easy to see that caffeine, the common denominator among them, must be a substance with almost universal appeal that may have stimulated people for many millennia. Some anthropologists speculate, without hard evidence, that most of the caffeine-yielding plants were discovered in Paleolithic times, as early as 700,000 B.C. Early Stone Age men, they say, probably chewed the seeds, roots, bark, and leaves of many plants and may have ground caffeine-bearing plant material to a paste before ingestion. The technique of infusing plant material with hot water, which uses higher temperatures to extract the caffeine, was discovered much later. Infusion brought to popularity the familiar caffeine-containing beverages, coffee, tea, and chocolate, and the more exotic ones, such as guarana, maté, yoco, cassina, and cola tea.

After the introduction of coffee and tea to the Continent in the seventeenth century, caffeine quickly achieved a pervasive cultural presence in Europe maintained to this day. In 1732 Bach composed the “Coffee Cantata,” a pæan with lyrics by the Leipzig poet Picander, who celebrated the delights of coffee (then forbidden to women of child-bearing age because of a fear it produced sterility) in the life of a young bride. It included an aria that translates as, “Ah! How sweet coffee tastes! Lovelier than a thousand kisses, sweeter far than muscatel wine!” In answer to denunciations of tea, Samuel Johnson confessed in 1757

to drinking more than forty cups a day, admitting himself to be a “hardened and shameless tea drinker, who has for twenty years diluted his meals with only the infusion of this fascinating plant…who with tea amuses the evening, with tea solaces the midnight, and with tea welcomes the morning.” Thomas De Quincey, the famous celebrant of opium, wrote, “Tea, though ridiculed by those who are naturally coarse in their nervous sensibilities, or are become so from winedrinking, and are not susceptible of influence from so refined a stimulant, will always be the favored beverage of the intellectual.”

By the twentieth century, the cultural life of caffeine, as transmitted through the consumption of coffee and tea, had become so interwoven with the social habits and artistic pursuits of the Western world that the coffee berry had become the biggest cash crop on earth, and tea had become the world’s most popular drink.

Although the chemical substance caffeine remained unknown until the beginning of the nineteenth century, both coffee and tea were always recognized as drugs. They excited far more comment, interest, and concern about the physical and mental effects we now attribute to their caffeine content than about their enjoyment as comestibles. You may be surprised to learn that, at the time of their discovery and early use, both coffee and tea and, much later, cola elixirs, were regarded exclusively as medicines. For example, Robert Burton, quoted above, who had neither seen nor tasted the beverage, describes coffee, in the section of his

Anatomy of Melancholy

devoted to medicines, as an intoxicant, a euphoric, a social and physical stimulant, and a digestive aid. He explic itly compares it with both wine and opium. By doing so, he identifies coffee with the effects of the drug caffeine, which, two hundred years later, scientists were to isolate as its pharmacologically active constituent.

In England, health claims and warnings, often fanciful, were touted almost as soon as the first cup of coffee was served. In the early seventeenth century, William Harvey (1578–1657), the physician famous for describing the circulation of the blood, used coffee for its medical benefits. In 1657 an English advertisement for coffee read, “A very whoesom and Physical drink, having many excellent vertues, closes the Orifice of the Stomack, fortifies the heat within, helpeth Digestion, quickneth the Spirits, maketh the Heart lightsom, is good against Eye-sores, Coughs, or Colds, Rhumes, Consumptions, Head-ach, Dropsie, Gout, Scurvy, Kings Evil, and many others.” In

Advice Against Plague,

published in 1665, Gideon Harvey (no relation to William), an English physician and medical writer, counseled, “Coffee is recommended against the contagion,” that is, against the bubonic plague that was then in the process of killing a quarter of London’s population. However, there were two sides to this debate: A translation of an Arabian medical text admonished English readers that coffee “causeth vertiginous headache, and maketh lean much, occasioneth waking…and sometimes breeds melancholy.”

The health claims for tea are even older. The Chinese scholar Kuo P’o, in about A.D. 350, in annotating a Chinese dictionary, describes preparing a medicinal drink by boiling raw, green tea leaves in kettles. Because boiling kills bacteria, the putative health benefits and claims for longevity may have had some foundation. In England, during the years of Cromwell’s Protectorate, the importation of tea was made acceptable only by its sale as a medicinal drink. A typical advertisement in a London newspaper at the time claimed, “That Excellent and by all Physitians approved China drink, called by the Chineans Tcha, by other Nations Tay alias Tea.”

The scientific history of caffeine itself began in 1819 when, as Henry Watts reports in his

Dictionary of Chemistry

(1863), Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge first isolated the chemical from coffee.

1

In 1827, a scientist named Oudry discovered a chemical in tea he called “thein,” which he assumed to be a different agent but that was later proved by another researcher, Jobat, to be identical with caffeine. Pure caffeine is a bitter, highly toxic white powder, readily soluble in boiling water. It is classified as a central nervous system stimulant and an analeptic, a drug that restores strength and vigor. After caffeine is ingested, it is quickly and completely absorbed into the bloodstream, which distributes it throughout the body. The concentration of caffeine in the blood reaches its peak thirty to sixty minutes after it is consumed, and, because it has a half-life from two and one-half hours to ten hours, most of the drug is removed within twelve hours. Other drugs can affect the way people react to caffeine: For example, smoking can increase the rate at which caffeine is metabolized by half, while alcohol reduces this rate, and oral contraceptives can decrease it by two-thirds.

In the twentieth century, medical studies have credibly linked caffeine to causing or aggravating PMS, lowering rates of suicide and cirrhosis, fostering more efficient use of glycogen and other energy sources such as body fat and blood sugars, improving performance of simple tasks, impairing short-term memory, potentiating analgesics, improving athletic performance, causing insomnia, alleviating migraine headaches, depressing appetite, relieving asthma, and so on. There remains considerable ambiguity about many of these putative effects. For example, some researchers have found that caffeine improves mood and performance only when people are aware that they have consumed it, which if true would mean that even the most widely acknowledged results of taking the drug are simply placebo effects!

However, if you have any doubt that caffeine is a drug, and a potent one, consider that a dose of only 1 gram, equivalent to about six strong cups of coffee, may produce insomnia, restlessness, ringing in the ears, confusion, tremors, irregular heartbeat, fever, photophobia, vomiting, and diarrhea. Severe intoxication may also cause nausea, convulsions, and gastrointestinal hemorrhage. The lethal dose for a two-hundred-pound adult is estimated at about 10 to 15 grams. Sudden withdrawal from caffeine-containing beverages frequently results in headaches, irritability, and difficulty concentrating.

The discovery of the enjoyment of coffee beans is credited by one legend to Kaldi, an Ethiopian goatherd said to have lived in the sixth or seventh century, who noticed that his goats became unusually frisky after grazing on the fruit of certain wild bushes.

Some say that, in coffee’s early days, Arabian peoples used the drink in a way still practiced in parts of Africa in the nineteenth century: They crushed or chewed the beans, fermented the juice, and made a wine they called

“qahwa,”

the name for which is probably the root of our word “coffee.” The first written mention of coffee occurs in tenth-century Arabian manuscripts. Possibly as early as the eleventh century or as late as the fifthteenth century, the Arabs began to make the hot beverage, for which they used the same name as the wine.

In the seventeenth century, at the same time that coffee was introduced to Europe from Turkey, Dutch traders brought tea home from China. In 1657 Thomas Garraway, a London pub proprietor, claimed to be the first to sell tea to the general public. The word “tea” is derived from the Chinese Amoy dialect word

“t’e,”

pronounced “tay.” In China, tea had been cultivated as a drink since, if Chinese legends are to be believed, the time of the Chinese emperor Shen Nung, to whom the discovery of tea, the invention of the plow, husbandry, and the exposition of the curative properties of plants are traditionally credited. An entry in his medical records dated 2737 B.C. (although certainly interpolated by a commentator much later) states that tea “quenches thirst” and also “lessens the desire for sleep.” As illustrated in the quotation above from Kakuzo Okakura, tea, after its arrival in Japan around A.D. 600, became the center of an elaborate ritualized enjoyment that distilled much of the essence of Japanese culture. In Europe, even though it was very expensive, tea’s use spread quickly throughout all levels of society and in certain circles displaced coffee as the favorite beverage.

John Evelyn, an English diarist and art connoisseur, writing in his

Memoirs,

in an entry dated 1637, describes the first recorded instance of coffee drinking in England: “There came in my time to the College, one Nathaniel Conopios, out of Greece…. He was the first I saw drink coffee; which custom came not into England until thirty years after.”

2

Perhaps because of the bohemian daring that infests universities and the early example set by Conopios, the first coffeehouse in England opened in Oxford in 1650. It was followed in 1652 by the first London coffeehouse, in St. Michael’s Alley, off Cornhill, under the proprietorship of an Armenian immigrant, Pasqua Rosée. The story of these English coffeehouses and a host of others over the next fifty years, at which not only coffee but tea and chocolate were commonly served, is a colorful chapter in literary, political, business, and social history. Often the occasion for lively discussion, visits to these early coffeehouses were recorded in the diaries of Samuel Pepys and many other contemporary sources. By the beginning of the eighteenth century, English café society had become so sophisticated that the noted social observer Sir Richard Steele was able to assign conversational specialties to the London houses: “I date all gallantry, pleasure and entertainment…under the article of White’s; all poetry from Will’s; all foreign and domestic news from St. James’s, and all learned articles from the Grecian.”

3

Curiously, neither coffee nor tea was responsible for the first infusion of caffeine into European bloodstreams: Chocolate, hailing from South America and carried across the Atlantic by the Spaniards, beat them to the punch by over fifty years. It was received with considerable favor, and, from the mid-seventeenth century, was often served alongside more caffeine-rich drinks in such London coffeehouses as the Cocoa Tree, a favorite hangout of the literati in the early eighteenth century. Chocolate has a much smaller amount of caffeine than coffee, tea, or colas. However, it contains large amounts of the stimulant theobromine, a chemical with a pharmacological profile somewhat similar to that of caffeine. The presence of theobromine augments the effects of the caffeine and probably helps to account for chocolate’s popularity, which rivals that of the beverages with significantly higher amounts of caffeine.