The World of Caffeine (19 page)

Read The World of Caffeine Online

Authors: Bonnie K. Bealer Bennett Alan Weinberg

These concerns and the corresponding disputes over the salubrity of coffee were essentially those voiced in Mecca, Cairo, and Constantinople more than a hundred years before, and they were, as we have seen, also based on the humoral theory propounded by Avicenna and other Islamic physicians. Overall the French public leaned heavily in favor of the caffeinated beverages, while the French physicians leaned heavily against them. La Roque describes a late-seventeenth-century face-off between the caffeine users and the doctors during which “the lovers of coffee used the physicians very ill when they met together, and the physicians on their side threatened the coffee drinkers with all sorts of diseases.”

20

One difference between these controversies in France and the Islamic disputes was the part played by the French vintners, who were not disposed to share their customers with coffee merchants and who therefore subsidized caffeine’s opponents in this war of letters. In 1679 Castillon and Fouqué, two physicians of the Faculty of Aix, rented the town hall and sent a freshman medical student, named “Colomb,” to argue a brief against coffee before the city magistrate and an audience of local physicians and laymen. In his thesis, entitled “Whether the Use of Coffee Is Harmful to the Inhabitants of Marseilles,” Colomb acknowledged that coffee was used in many nations, where it had often entirely displaced wine, while arguing that, nevertheless, it was in every way inferior to that more familiar beverage. With characteristic Gallic xenophobia, he then damned coffee as an unwholesome foreign introduction, brought to the attention of men by goats and camels. As to its health effects, he asserted that coffee had been accepted by European physicians on the strength of selfserving Arab testimonials disseminated to develop new markets for their produce. Coffee, he continued, had no value as a cure for distempers and was in humoral terms hot, not cold as its proponents claimed, and that, because it consumed the blood, it caused impotence, emaciation, and palsy. Colomb concluded:

Some assure us that coffee is a cooling drink and for this reason they recommend us to drink it very hot…. The burned particles, which it contains in large quantities, have so violent an energy that, when they enter the blood, they attract the lymph and dry the kidneys. Furthermore, they are dangerous to the brain for, after having dried up the cerebro-spinal fluid and the convolutions, they open the pores of the body, with the result that the somniferous animal forces are overcome. In this way the ashes contained in coffee produce such obstinate wakefulness that the nervous juices are dried up;…the upshot being general exhaustion, paralysis, and impotence. Through the acidification of the blood, which has already

assumed the condition of a river-bed at midsummer, all the parts of the body are deprived of their juices, and the whole frame becomes excessively lean.

21

His references to “juices” designate the body’s fluids, the balance of which, according to humoral theory, determined a person’s health. Once again, it is easy tc see the actions attributable to caffeine among the effects Colomb describes, including what was then often called “desiccation,” or increased urination, and its power to overcome “somniferous animal forces” and induce “obstinate wakefulness.”

Colomb’s diatribe did not dissuade many caffeine users, for coffee had already insinuated itself into popular affections and was not to be easily displaced. In France, where doctors of medicine were lampooned in contemporary plays as pretentious pseudo-savants, their anticoffee blandishments won little regard from the public. Therefore, despite the reformatory admonitions of physicians such as Castillon and Fouqué, coffeehouses continued to increase in popularity, as did coffee drinking in the home, and the merchants imported green coffee from the East in ever increasing quantities to satisfy the demand.

Though Colomb’s exhortations and the admonitions of the physicians of Aix failed to impress the public at large, they did help to prejudice the views of the medical community for some time. Partly as a result of Colomb’s arguments, most French doctors toward the end of the seventeenth century advised against the use of coffee as a comestible, maintaining that it was a potent and potentially dangerous drug that should be taken by prescription only. Lurid stories about coffee poisoning abounded. When Jean Baptiste Colbert (1619–83), financier and statesman, died, it was whispered that his stomach had been corroded by coffee. According to another letter penned by Elizabeth Charlotte, duchess of Orléans, an autopsy revealed that the princess of Hanau-Birkenfeld had hundreds of stomach ulcers, each filled with coffee grounds, and it was concluded that she had died of coffee drinking.

Not every Gallic scientist was so easily persuaded of the evils of caffeine. Philippe Sylvestre Dufour (1622–87), an archaeologist, joined with Charles Spon (1609–84), a Lyon physician, scholar, and Latin poet, and Cassaigne, another local physician, to perform a chemical analysis of coffee. Based on this collaborative effort, Dufour wrote his famous work mentioned at the opening of this chapter, which was reissued in many editions and translations, but which is now only to be found in rare book rooms,

Traitez Nouveaux & curieux Du Café, Du Thé et Du Chocolate

(1685).

22

This was the first book to attempt to derive the pharmacologic effects of coffee from its chemical constituents. Among its other benefits, Dufour asserted that coffee counteracted drunkenness and nausea and relieved menstrual disorders. He repeated other long-standing claims for the drink, including that it relieved kidney stones, gout, and scurvy, and also stated that it strengthened the heart and lungs and relieved migraine headaches. He noted with surprise that some people can sleep at bedtime even immediately after drinking coffee. His overall judgment was a favorable one: “Coffee banishes languor and anxiety, gives to those who drink it, a pleasing sensation of their own well-being and diffuses through their whole frame, a vivifying and delightful warmth.”

23

(Dufour also wrote an earlier book about the preparation of the caffeinated beverages,

The Manner of Making

Coffee, Tea, and Chocolate as It Is Used by Most Parts of Europe, Asia, Africa, and America, with Their Virtues

[Lyon, 1671; London, 1685].)

Dr. Louis Lemery (1677–1743) published

Traité des Aliments

(Paris, 1702; translated by John Taylor and printed in London as

A Treatise of Foods,

1704), in which he summarized what he saw as the beneficial and harmful effects of coffee. Among the good effects were: strengthening the stomach, speeding digestion, abating headaches, alleviating hangovers, stimulating the production of urine and flatulence and the onset of menses, and stimulating the memory and imagination. The bad effects included emaciation and loss of sexual appetite.

24

In the English edition, while ascribing to chocolate most of the same pharmacological effects as coffee, he also credited it with allaying “the sharp Humours that fall upon the Lungs,” a clear reference to caffeine’s antiasthmatic properties, and with promoting “venery” as opposed to diminishing the erotic impulse.

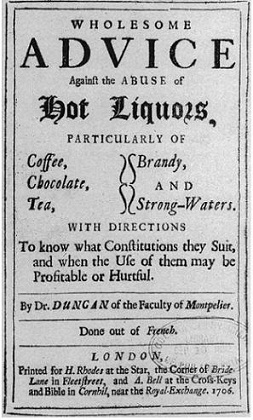

Toward the close of the seventeenth century, Daniel Duncan (1649–1735), a Scottish physician on the faculty of Montpellier, wrote a polemic addressing all three known caffeinated beverages and throwing in brandy and distilled spirits for good measure. His book, published in France in 1703, attained considerable circulation in that country and was translated into English under the title

Wholesome Advise against the Abuse of Hot Liquors, Particularly of Coffee, Chocolate, Tea,

Brandy, and Strong-Waters.

This 1706 London edition published by H.Rhodes was widely referenced as an authority throughout the eighteenth century. Dr. Duncan saw himself as a man of moderation and reason, one who fairly considered all sides of every question and eschewed extremes of all sorts. On the first page of his book he states, in what was an apparently unknowing recapitulation of a compelling neo-Platonic Augustinian theodicy, that any being, however base, is better than nothing. “There’s nothing absolutely good, but God…. Among Creatures there’s nothing absolutely Bad, for [that] they are the workmanship of that infinitely good being, communicates to each of them some degree of that goodness.”

25

After four or five pages more in this vein, he continues:

Title page:

Wholesome Advise against the Abuse of Hot Liquors, Particularly of Coffee, Chocolate, Tea, Brandy and Strong-Waters, with

directions, To know what Constitutions they Suit, and when the Use of them may be Profitable or Hurtful,

by Dr. Duncan of the Faculty of Montpelier, London, Printed for H.Rhodes at the Star, 1706. This book, by a Scottish physician who took a position on the medical faculty in France, warned against the dangers of excessive coffee, tea, and chocolate consumption. (Philadelphia College of Physicians)

That’s the design of this Treatise, and to make a particular Essay upon this General Maxim, by describing the Good and Bad Use of Hot Things, and especially of Coffee, Tea, Chocolate, and Brandy, of which abundance of Good has been said by some, and abundance of Ill by others.

26

A garrulous moralist, Duncan saw in the pleasures of coffee, tea, and chocolate a dangerous snare. “Voluptuousness,” he explains, “creates in us an Aversion to good Things, because they are not pleasant; and an inclination to bad Things, because they please us.” He adds, “Both these things happen in the use of Coffee, Chocolate, and Tea.” Coffee’s bitterness is so pronounced that coffee at last becomes “agreeable …not so much by Custom, as by the mixture of Sugar…and since it became pleasant, it’s become pernicious by the abuse of it.” Calling them all “liquors,” Duncan pronounces a single verdict on all three caffeinated beverages, suggesting how strongly their common nature as vehicles of a drug was suspected and providing a vivid impression of how completely caffeine had conquered France by the turn of the eighteenth century:

The use or abuse of those Liquors has become almost universal. Towns, villages, and all sorts of people are in a manner over-flow’d by them. So that not to know them is reckoned barbarous. They are in all Societies, and to be found everywhere. Formerly none but Persons of Qualities or Estate had them, but now they are common to high and low, rich and poor, so that if they were poison, all mankind would be poison’d; and if they be good medicines, all men may reap advantage by them when they come to know the true use of them.

Duncan finally issues the balanced judgment he promised to deliver at the beginning of his book: that coffee, chocolate, and tea have good and bad effects, depending on who is using them and how much he is using, but that none of them is either a deadly toxin or a panacea. However, he also observes, too much of any caffeinated beverage is harmful to anyone, and even a small amount can be harmful to some people. Duncan concludes, as had so many before him, that many of coffee’s deleterious effects resulted from its diuretic actions, or “desiccative influence.”

27

Although admitting that coffee could be beneficial for those “whose blood circulates sluggishly, who are of a damp and cold nature,” he asserted that the French did not suffer from this problem and so joined other French physicians in their opposition to its indiscriminate use in his adopted country.

Meanwhile, in England, despite republication of Duncan’s cautionary book there, caffeine continued to grow in popularity. And, although England had not been among the first Western nations to become alert to coffee, none took to the drink quite so avidly; in consequence, from 1680 to 1730, Londoners consumed more coffee than the inhabitants of any other city in the world.

The caffeine in coffee stimulated and sustained the investigations of the early members of the Royal Society, and in this way helped Robert Boyle create the science of chemistry and make possible caffeine’s discovery. Another remarkable tale of caffeine and the history of science depicts a man fifty years Boyle’s senior, William Harvey (1578–1657), physician and professor of anatomy, the greatest medical researcher and theoretician of his century, and a true pioneer of caffeine use in England.

Harvey, who discovered and demonstrated the circulation of the blood and is acknowledged, with Vesalius, as one of the two primary founders of modern scientific medicine, was also one of the first Europeans who is known to have taken caffeine regularly. He drank coffee for more than fifty years before coffeehouses came to London, at a time when he was forced to import his own supply of beans, the habit and the trade connections both having been acquired during his student days in Padua.

Harvey was born in Folkestone, Kent, the oldest of nine scions of a wealthy international trader. Five of his six brothers, following in their father’s footsteps, became “Turkey merchants,” as Englishmen called those who traded with the Eastern nations. Harvey’s singular academic bent was recognized early, and when he was ten years old he was enrolled in Kings School, where he was rigorously drilled in the Latin and Greek that was to give him access to the intellectual inheritance of the Classical world. At sixteen, he matriculated at Caius College at Cambridge, a school popular, then as now, among students interested in becoming physicians. (It had been named for Dr. John Caius, who had shared an apartment with Vesalius when both were students in Padua.) Harvey received his B.A. in 1597 and two years later embarked to study medicine in Italy. In 1602 he was granted his doctoral diploma from Padua. Thereafter, he returned to London, where, over the years, his upscale medical practice included James I, Charles I, and Lord Chancellor Bacon. Here he engaged in the methodical and creative investigations that led to the formulation of his history-making theory of the circulation of the blood.