The World of Caffeine (14 page)

Read The World of Caffeine Online

Authors: Bonnie K. Bealer Bennett Alan Weinberg

During much of the centuries-long struggle between the Ottoman and Hapsburg Empires, the Armenians, as Christian subjects of the Turks, traveled and traded up and down the Danube, freely crossing the shifting border between the contesting powers. It is therefore no surprise to learn that an Armenian, one Pascal, whether he came to Paris on his own or in attendance to Suleiman Aga, should have become, in 1672, the first to sell coffee to ordinary Parisians. Until then, few people had had the opportunity to drink it. As Heinrich Edward Jacobs says, “It was consumed only occasionally in the houses of distinguished persons, whose family economy was self-contained.”

14

Pascal the pitchman, spotting an opportunity, aimed at the bourgeois market when he erected one of the 140 booths that filled nine streets with commercial exhibits and offerings in the gala annual fair in St. Germain, just across the Seine and outside the walls of Paris proper. His

maison de caova

was designed as a replica of a Constantinople coffeehouse, and its exotic Turkish trappings, when all things Turkish were in vogue among the élite, drew curious members of the public with its mystery and with the novel sweet, roasted scent of fresh coffee. Carrying trays of

le petit noir,

as it was called, black slave boys darted among members of the street crowd who, either from shyness or inability to find an open space, hung back from approaching the stall itself. Pascal recognized that to make headway with the public, coffee would have to be as cheap as

wine; and by importing directly from the Levant and cutting out the Marseilles middlemen, he was able to sell the rare drink for only three sous a cup.

Flush with his success at the fair, the enterprising Pascal decided to open what he intended would be a permanent coffeehouse at Quais de l’École near the Pont Neuf. When business proved slow, he instituted the practice of sending his waiters, carrying coffeepots heated by lamps, from door to door and through the streets, crying “Café! Café!” Despite this aggressive retailing strategy, he soon went broke, packed up, and moved to London. Once there, he may well have headed straight for St. Michael’s Alley in Cornhill, where London’s first coffeehouse had been opened twenty years before by another Armenian immigrant, who, confusingly enough for us, was also named Pascal.

Great is the vogue of coffee in Paris. In the houses where it is supplied, the proprietors know how to prepare it in such a way that it gives wit to those who drink it. At any rate, when they depart, all of them believe themselves to be at least four times as brainy as when they entered the doors.

—Charles-Louis de Secondat, baron de La Brede et de Montesquieu (1689–1755), personal letter, 1722

Pistols for two; coffee for one.

—Wry commonplace about the orders given before dueling, Paris,

La belle Epoque

The world’s first café, a French adaptation of the Islamic coffeehouse, was opened in 1689 in Paris by François Procope. Procope, a Florentine expatriate, started his food service career as a

limonadier,

or lemonade seller, who attracted a large following after adding coffee to his list of soft drinks. Undeterred by Pascal’s recent failure, Procope decided to target a better class of customers than had the Armenian by situating his establishment directly opposite the Comédie Française, in what is now called the rue de I’Ancienne Comédie. His strategy worked. As the London coffeehouses were doing across the Channel, it attracted actors and musicians and a notable literary coterie. Over the two centuries of its operation as a café, the Procope served as a haunt for such writers as Voltaire, a maniacal coffee addict, Rousseau, Benjamin Franklin, Beaumarchais, Diderot, d’Alembert, Fontanelle, La Fontaine, Balzac, and Victor Hugo. Like Johnson’s famous armchair in Button’s coffeehouse, Voltaire’s marble table and his favorite chair remained among the café’s treasures for many years. Voltaire’s favorite brew was a mixture of chocolate and coffee, which gave him effective doses of both caffeine and theobromine. He is quoted as having remarked of Linant, a pretentious and untalented versifier, “He regards himself as a person of importance because he goes every day to the Procope.”

Like its English counterparts, the Café Procope became a center for political discussions. Robespierre, Marat, and Danton convened there to debate the dangerous issues of the day, and were supposed to have charted the course that led to the revolution of 1789 from the café. Napoleon Bonaparte, while still a young officer, also frequented the Café Procope, and was so poor that the proprietor prevailed on him to leave his hat as security for his coffee bill. The Café Procope was an astonishing success, and from its advent coffee became established in Paris. By one accounting, during the reign (1715–74) of Louis XV there are supposed to have been six hundred cafés in Paris, eight hundred by 1800, and more than three thousand by 1850. According to another more modest reckoning, there were 380 by 1720. Whatever the exact numbers, it is clear that, from the beginning of the eighteenth century, cafés proliferated as rapidly in Paris as the coffeehouses had in London in the last half of the seventeenth century.

Another itinerant Parisian coffee seller, Lefévre, also opened a café near the Palais Royal around 1690. It was sold in 1718 and renamed the Café de la Régence, in honor of the régent of Orléans. Well located to attract an upscale crowd, the café attracted the nobility, who assembled there after withdrawing from paying homage to the French court. The café drew many of the Procope’s customers, and the list of literary and other patrons reads like a Who’s Who of French literature and society over the next two centuries. Robespierre, Napoleon, Voltaire, Alfred de Musset, Victor Hugo, Theophile Gautier, J.J.Rousseau, the duke of Richelieu, and Fontanelle are still remembered in connection with their visits there. In his

Memoirs,

Diderot records how his wife gave him nine sous every day to pay for coffee at the Régence, where he sat and worked on his famous

Encyclopédie.

The historian Jules Michelet (1798–1874), writing many years later, gives a vivid account of the ways in which coffee and the café changed and enlivened Parisian life:

Paris became one vast café. Conversation in France was at its zenith For this sparkling outburst there is no doubt that honor should be ascribed in part to the auspicious revolution of the times, to the great event which created new customs, and even modified human temperament—the advent of coffee.

This sudden cheer, this laughter of the old world, these overwhelming flashes of wit, of which the sparkling verse of Voltaire, the

Persian Letters,

give us a faint idea!

15

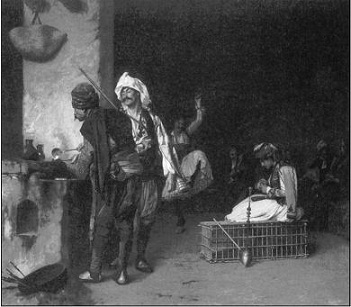

Café House, Cairo,

by Jean-Léon Gérome (1824–1904). An example of nineteenth-century French Orientalism, this oil painting shows the coffeehouse as a setting for casting bullets and is reminiscent of the tradition of the French café as the scene of real and imagined revolutionary intrigue. (Metropolitan Museum of Art, bequest of Henry H.Cook, 1905)

Like the coffeehouses of London, the Parisian cafés attracted a heterogeneous collection of patrons. Charles Woinez announced in his leaflet periodical

The Café, Literary, Artistic, and Commercial

in 1858, “The Salon stood for privilege, the Café stands for equality.” A similar observation was made in an early-eighteenth-century broadside:

The coffeehouses are visited by respectable persons of both sexes: we see among the many various types: men-about-town, coquettish women, abbés, country bumpkins,

nouvellistes

[purveyors of news], the parties to a law-suit, drinkers, gamesters, parasites, adventurers in the field of love or industry, young men of letters—in a word, an unending series of persons.

16

Despite this pervasive heterogeneity, many Paris cafés catered to special clienteles. Café Procope’s chief rival in regard of attracting poets was the Café Parnasse.

17

The Café Bourette also attracted the literati, the Café Anglais was favored by actors and the after-theater crowd, the Café Alexandre was patronized by musical performers and composers, the Café des Art drew opera singers and their entourage, and the Café Boucheries was a place where directors came to hire actors for new productions. But the arts and letters did not have an exclusive hold on the institution. The Café Cuisiner was the favorite of coffee connoisseurs and featured a variety of exotic blends. The Café Defoy was known for sherbet as well as coffee. The Café des Armes d’Espagne was an army officers’ hangout. The Café des Aveugles, which featured musical entertainment by blind instrumentalists, was a den of prostitution.

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, after the Procope and the other cafés had lost their literary reputations, Paul Verlaine, the leader of the Symbolist poets, made the Procope his favorite haunt and thereby partly restored, for a time, its former glory The Procope is still in business today as a restaurant.

The epochal conflict between the Ottoman and Hapsburg Empires well merits the Yiddish epithet

“fershlepte kraynk,”

which means “long drawn-out difficulty,” for the military, political, and economic rivalry between them began in the fifteenth century and did not abate until almost the end of the nineteenth. As is true for any longtime enemies, each influenced the other, in this case by means of example and trade and through the agency of writers, travelers, merchants, and diplomats. The network of rivalries within Christian Europe, especially the contest between the Protestant Bour-bons and the Catholic Hapsburgs and the vagaries of Louis XIV, who one year was more jealous of the Austrians and the next was more fearful of the Turks, created problems for the West, opportunities for the East, and confusion for everyone.

18

The ratification of one of the many peace treaties concluded by the Viennese and the Turks was the occasion for the introduction of coffee to the city. Kara Mah-mud Pasha was a Turkish ambassador who, with an entourage of three hundred, arrived in 1665 to open an embassy in the court of Emperor Leopold I. He spared no effort to impress the local citizens. Kara arrived in Oriental splendor to which the Europeans were unaccustomed, and among his exotic household were camels, Arabian stallions, two coffee brewers, Mehmed and Ibrahim, and a supply of coffee beans. We know that the brewers were kept busy during their several months’ stay, because the city archives record many complaints about the unusually high wood consumption of the Turks, who kept a fire always burning in order to assure a fresh supply of the drink.

19

To some extent the habit caught on with the natives. After the ambassador and his retinue departed in 1666, city records report private trade in coffee and that an Oriental trading company, which operated from 1667 until the invasion of 1683, was a primary source for the beans.

The traditional account of coffee’s first appearance in Vienna is considerably different. This folk history dates coffee’s arrival to the 1683 Turkish attempt on the city, a gigantic undertaking, in support of which General Kara Mustafa had led an army of more than three hundred thousand Turkish troops up the Danube from the heartland of the distant eastern empire. The beleaguered city was ringed with twenty-five thousand Turkish tents. Kara settled in for a prolonged siege, during which he sent raiding parties into the surrounding countryside, from the Alps to the Bavarian border. Meanwhile, the Islamic equivalent of the Army Corps of Engineers began tunneling under Vienna’s walls, preparing an entrance for the Janissaries, the empire’s elite troops, to storm. As the situation worsened, the isolated Viennese sent a scout through the Muslim lines to deliver a message to their allies, who had massed just upriver, that the counterattack could be delayed no longer. These Christian troops, led by King John III Sobieski of Poland and Duke Charles of Lorraine, arrived just as the city’s troops poured out of the gate, catching the invaders by surprise and forcing the Islamic general to abandon his camp and hastily withdraw up the Danube. The defeated Turkish armies, in their retreat, took with them over eighty-five thousand slaves captured on these raids, including fourteen thousand nubile girls who would almost certainly be tapped for initiation into the suffocating luxury, enforced helplessness, and fatal intriguing of the Turkish harem. Because of his failure to take Vienna, Mustafa was met on the way home by assassins and suffered strangulation by the gold cord, a death reserved for the sultan’s most intimate enemies.

The Viennese enjoy recalling the glories of their history, and many earnestly commemorate the siege of 1683. As part of this remembrance, Austrian schoolchildren are taught the proverbial story of Georg Kolschitzky, a Pole, who happened to be in town when the assault began, and who is honored for his heroic part in defending the city. Kolschitzky was an adventurer who had traveled widely in the Ottoman domains, serving for a time as a dragoman, or interpreter, in the capitals of the East. Happily, because of his intimate knowledge of the Turkish language and customs, he was able to volunteer service to Vienna as a surveillance agent. On August 13, 1683, Kolschitzky and his servant Milhailovich, each in Oriental disguise, wandered around and through the Turkish encampment northwest of the city. The information they collected about the size and disposition of the enemy forces proved invaluable, or so the story goes. Others say that he was the scout who carried a letter through the enemy lines telling the duke of Lorraine when to attack.