The World of Caffeine (11 page)

Read The World of Caffeine Online

Authors: Bonnie K. Bealer Bennett Alan Weinberg

Fabulous stories, from diverse sources, proliferate surrounding Montezuma II’s chocolate consumption. There are Montezuma II’s own accounts of the splendor of his court. We also have

The True History of the Conquest of Mexico,

by Bernal Diaz del Castillo (1572), written in Guatemala by the eighty-year-old former comrade of Cortés who seemed to be committed to recording the literal truth, although its trustworthiness is compromised by the fact that his recollections were decades old. In addition, there survive many sycophantic, purple accounts penned by Cortés’ admirers, often obviously exaggerated. For example, one writer tells us that more than two thousand pitchers of chocolate were consumed daily in the palace.

7

Others say that Montezuma, like some of the Roman emperors, sent runners to the mountains for snow, which he

mixed with chocolate to create a sherbet. Legend even has it that cleaning up after Montezuma’s chocolate bouts was a difficult but rewarding job. For as he emptied each golden goblet, he tossed it out the palace window into the lake below.

If we put aside these exaggerated chronicles, the importance of cacao at the time of the conquest remains evident in the

Codex Mendoza,

prepared by an Aztec artist for Antonia de Mendoza, the first Spanish viceroy of Mexico. One of the few surviving contemporary native documents, it celebrates cacao’s prominence, illustrating large sacks of beans among precious commodities that included cotton, honey, feathers, and gold, paid by the surrounding tribes to the Aztecs in tribute.

8

It is nearly certain that cacao seeds were the first caffeinated botanicals to reach Europe in historical times, arriving with Columbus, who, on his return from his fourth trip to the New World in 1502, presented the pods to King Ferdinand of Spain. However, the record contains no indication that the virtues of the plant were known to the Spanish even in the New World until 1528,

9

when Cortés watched the preparation and shared in the consumption of the fortifying drink,

cacahuatl,

at the court of Montezuma II. As Cortés encountered it, chocolate was a bitter brew of crushed, roasted cacao beans, steeped in water, and thickened with corn flour, to which vanilla, spices, and honey were sometimes added. There is no evidentiary basis for the frequent claim that Cortés brought the beans to Spain for the enjoyment of the royal family. However, although he never presented the beans to his sovereign, Cortés was the first to bring news of their use. In an excited letter to King Charles V of Spain, Cortés called chocolate the “drink of the gods,” and in so doing ultimately provided the scientific names for both the species,

Theobroma cacao,

and for caffeine’s pharmacological cousin, theobromine, responsible for some of chocolate’s stimulating powers. Both terms are compounded from Latin roots of the same meanings. During the middle of the sixteenth century, after some unknown Spaniards crossed the Atlantic with the secrets of chocolate making, the Spanish aristocracy immediately adopted the fashion of their Aztec counterparts, and the initiation of caffeine and theobromine into the culture of Europe began. Cortés, who during his previous visits had destroyed his image as a benevolent deity by executing Montezuma and his heir and conquering and looting the Aztec empire, returned to the New World, to establish cacao plantations for Charles V in Haiti, Trinidad, and Fernando Po.

“Cacao” and “chocolate” and their cognates are today among the most widely used non-Indo-European words in the world. Surprisingly, no one is certain exactly how or even if the roots of these words are related.

“Cacao” derives from

“kakawa,

” which is thought to have originated as a word in what linguists have recently decided was the Olmec language, a member the Mixe-Zoquean family of languages, the source of many important loan words in later Mesoamerican languages. Although no texts from the period survive, scholars have inferentially assigned

“kakawa”

to the Olmec vocabulary of around 1000 B.C.

10

Sometime between 400 B.C. and A.D. 100, the Maya, the Olmecs’ Izapan successors, presumably borrowing from this Olmec word, also began using

“kakawa”

to designate the domesticated cacao plant and the beans harvested from it. (“Cocoa” is simply a corrupt form of “cacao.”)

In Guatemala, the original Mayan homeland, in the village of Rio Azul, a wellpreserved pottery jar dating from before A.D. 500 and containing cacao residues, found in 1984, bears the Mayan glyphs for

“ka-ka-w(a).”

This is the earliest known inscription of the root of the word “cacao.”

11

The first glyph, “ka,” represents a comb or feather; the second glyph, also pronounced “ka,” represents a fish fin; and the third, “w(a),” is simply the sign for a final “w.” This late-fifth-century jar, discovered in a opulent Classic Maya tomb replete with chocolate-drinking paraphernalia, has a stirrup handle and a screw-on lock-top lid. Its stucco surface is brightly painted to resemble a jaguar, with a half-dozen hieroglyphs, including two that designate cacao.

12

When this jar was submitted to the laboratories of the Hershey Company of Pennsylvania, traces of both caffeine and theobromine were identified within the lid. This Mayan jar contains the oldest caffeinated comestible residues ever discovered.

The importance of cacao to the Indians at the time of the conquest is betrayed in the rich variety of words they used to differentiate its vegetable sources. The Spanish naturalist and physician to Phillip II, Francisco Hernandez (1530–87), was sent to Mexico to discover and catalogue plants with medicinal value. In his work on the plants of the Americas, he lists more than three thousand species and gives their native names. Hernandez mentions four cultivated varieties of the tree:

13

cuauhcacahuatl,

“wood cacao”;

mecacahuatl,

“maguey cacao”;

xochicacahuatl,

“flower cacao”; and

tlalcacahuatl,

“earth cacao.”

As noted above, the English word “chocolate,” which designates various preparations of cacao, has an etymologically uncertain relationship to “cacao.” It derives from the Spanish usage

“chocolatl,

” which first appeared in the New World sometime after 1650. But no one seems to know how or why the Aztec word for chocolate,

“cacahuatl,

” formed by combining the Mayan

“kakawa”

with the word

“atl,”

meaning water, was replaced by

“chocolatl.

” Many reputable reference books derive

“chocolatl”

from a supposed Nahuatl word for the drink that was unrelated to

“kakawa,”

but recent scholarship proves this word does not actually appear in the pre-Columbian sources of the language. Others blame the coinage on Spanish squeamishness over using a word reminiscent of a cant term for excrement, especially as the root “caca” in Latin and the Romance languages is frequently found in combinations that form other words relating to defecation. All we know for certain is that, from wherever it came,

“chocolatl”

quickly spread, replacing the Aztec word for the drink, and became the source of the word for chocolate in most languages today

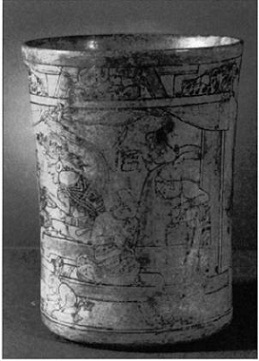

Late Classic Maya vase (A.D. 672–830), of gray buff clay, about ten inches high and seven inches in diameter, showing a woman pouring chocolate from one vessel to another in a palace setting. This is the earliest depiction of the froth-making process that characterized native preparations of cacao. (The Art Museum, Princeton University, Museum Purchase, gift of the Hans A.Widenmann, class of 1918, and Dorothy Widenmann Foundation)

The earliest depiction of chocolate making appears on an eighth-century Late Classic Maya vase, now in the Princeton Art Museum. The vase shows a woman pouring chocolate from a smaller jar into a larger one, a transfer intended to bring up the foam, probably considered the most desirable part of the drink in those days as it certainly was in later Aztec times. Not much is known for certain about the Late Classic Maya recipes, but it appears that they confected a wide variety of both hot and cold drinks and “gruels, porridges, powders, and probably solid substances,”

14

to which were added spices and other flavors. The only spice the Maya added to chocolate that we can identify today with certainty is the chili pepper.

Modern scholarship suggests that the Aztec chocolate drink, which was usually taken cold, was made from beans that had been dried in the sun and fermented in their pods. The beans were then crushed, roasted in clay pots, and ground into paste in a

concave stone called a “metate.” It is believed that vanilla and various spices and herbs were added and that maize flour was sometimes used to palliate the bitter taste. The resulting paste was shaped into small wafers or cakes which were left outside to cool and harden in the shade. When ready for use, the finished cakes were crumbled, mixed with hot water, and stirred rapidly with tortoiseshell spoons. Here is one of the earliest surviving European accounts of native methods of making chocolate from cacao beans, published in 1556 by a man idenrified only as having recently returned to Venice from an American expedition in the company of Cortés, in which he praises the fortifying power of the drink:

These seeds which are called almonds or cacao are ground and made into powder, and other small seeds are ground, and this powder is put into certain basins… and they put water on it and mix it with a spoon. And after having mixed it very well, they change it from one basin to another, so that a foam is raised which they put in a vessel made for the purpose. And when they wish to drink it, they mix it with certain small spoons of gold or silver or wood, and drink it, and drinking it one must open one’s mouth, because being foam one must give it room to subside, and go down bit by bit. This drink is the healthiest thing, and the greatest sustenance of anything you could drink in the world, because he who drinks a cup of this liquid, no matter how far he walks, can go a whole day without eating anything else.

15

Thomas Gage, in

New Survey of the West Indies

(1648), an important source of information about the Mayas in their post-Columbian twilight, describes the typical Indian methods of preparing and consuming the drink as he encountered them a century later:

The manner of drinking it is diverse.... But the most ordinary way is to warme the water very hot, and then to poure out half the cup full that you mean to drink; and to put into it a tablet [hardened spoonful of chocolate paste] or two, or as much as will thicken reasonably the water, and then grinde it well with the Molinet, and when it is well ground and risen to a scumme, to fill the cup with hot water, and so drink it by sups (having sweetened it with sugar) and to eat it with a little conserve or maple bred, steeped into the chocolatte.

16

Gage assumes that the use of the moliné, or stirring rod with which the liquid was beaten to a frothy consistency, and the use of sugar were native practices. However, in light of information from other sources, we must assume that both practices had, by the middle of the seventeenth century, been widely adopted in America in imitation of early Spanish innovators. Compounding his error about the moliné, Gage adds to the etymological confusion over the origin of the word “chocolate” by providing his own factitious but widely quoted onomatopoetic account that word was born when the “choco choco choco” sound of the whipping moliné was combined with the Nahuatl word for water.

Despite the new popularity of hot chocolate among the Maya, the old Maya custom of consuming chocolate thick and cold seems to have survived until Gage’s time, at least at religious or civic festivals. As he observed:

There is another way yet to drink chocolatte, which is cold, which the Indians at feasts to refresh themselves, and it is made after this manner: The chocolatte (which is made with none, or very few, ingredients) being dissolved in cold water with the Molinet, they take off the scumme or crassy part, which riseth in great quantity, especially when the cacao is older and putrefied. The scumme they lay aside in a little dish by itself, and then put sugar into that part from whence was taken the scumme, and then powre it from on high into the scumme, and so drink it cold.

17

europe wakes up to caffeine

monks and men-at-arms

Europe’s First Caffeine Connections

The main benefit of this cacao is a beverage which they make called Chocolate, which is a crazy thing valued in that country. It disgusts those who are not used to it… [but] is a valued drink which the Indians offer to the lords who come or pass through their land. And the Spanish men—and even more the Spanish women—are addicted to the black chocolate.

—José de Acosta, S J., commenting on chocolate use in Mexico,

Natural and Moral History,

1590

In 1502, on his fourth voyage across the Atlantic, Columbus overshot Jamaica and anchored at Guanaja, one of what are today called the Bay Islands, thirty miles off the Honduran coast. While stopping among the Maya villagers, he became the first European on record to have encountered cacao beans. On August 15, Columbus was among the members of a scouting party dispatched from the Spanish ships that encountered two 150-foot canoes propelled by slaves tied to their stations by their necks. One of these great boats, which resembled Venetian gondolas, was captured without incident. It turned out to be filled with trading goods, including cotton clothing, stone axes, and copper bells from the Yucatán Peninsula and carried women and children under a shelter of palm leaves. A description of the meeting was recorded in a 1503 Spanish account, written in Jamaica by Columbus’ son, Ferdinand, and finally published, in a corrupt Italian edition, seventy years later, in Venice:

For their provisions they had such roots and grains as are eaten in Hispaniola…, and many of those almonds which in New Spain [Mexico] are used for money. They seemed to hold these almonds at a great price; for when they were brought on board ship together with their goods, I observed that when any of these almonds fell, they all stooped to pick it up, as if an eye had fallen.

1

What he called “almonds” were actually cacao beans. Columbus’ party was impressed by the high value placed on the beans by the natives; but because they had no translator, they failed to discover cacao’s use in making chocolate. Nevertheless, Columbus brought back some of the pods for King Ferdinand of Spain, and these were the first caffeinated botanicals known to have reached Europe.

As we have seen, although Cortés delighted to find in cacao an agent that could stimulate and fortify his soldiers and recommended cultivation of the plant to the young Charles V of Spain, the stories attributing to Cortés the actual delivery of beans to Spain or the preparation of chocolate in Spain have no historical basis. The inventory of Cortés’ American booty, supplied to the king to document the payment of the crown’s share, never mentions cacao. Nor was cacao among the novelties exhibited to the king in 1528 by the returning Cortés, including Europe’s first bouncing rubber ball, a menagerie complete with jaguars and armadillos, and miscellaneous noblemen and human oddities from the New World.

No one knows, or is likely ever to know, which of the myriad commercial, military, or religious Spanish enterprises first brought the beverage to the court. However, chocolate’s earliest documented appearance in Spain came in 1544, when a delegation of Dominican friars transported a group of Maya dignitaries to meet Prince Philip (later Philip II), son of Charles V. The visiting Americans carried rich gifts for Philip, among them vessels filled with chocolate. In 1585, the first recorded commercial shipment of cacao beans reached Seville.

Charles V, His Most Catholic Majesty, is credited with achieving the happy admixture of chocolate and sugar, a confection that yielded a drink not only palatable but delicious to Europeans. Cane sugar, imported from the Orient at great cost, had already become available in Europe by the time cacao arrived, and the king blended the two to make a fabulously expensive drink that became a rage at the Spanish court. The cacao paste was also often mixed with vanilla and sometimes with rose water or cinnamon, nutmeg, almonds, pistachios, or even musk, cloves, allspice, or aniseed. Chocolate was enjoyed cold and thick at first, just as it had been by the Aztecs, but within a few years an unknown Spaniard thought up the idea of serving it hot, and a whole new tradition, restoring a more ancient preference of the Maya in this respect, began. Chocolate was thereafter served from a pot, similar to the coffeepot but with the addition of the moliné, a stick for stirring and mixing. The cups into which the chocolate was poured were taller and slimmer than those for coffee or tea, and from their shapes it is possible to determine which of these beverages is being consumed in paintings of the period.

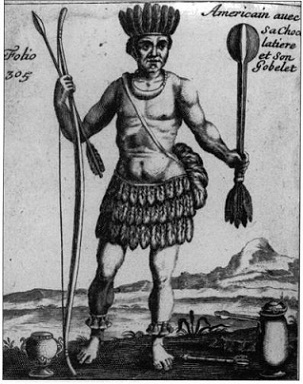

This late-seventeenth-century French engraving features the artist’s conception of an Aztec in feathered regalia, armed with bow and arrow and feathered club, and illustrates a pot for making chocolate, the moliné used for stirring the froth, and the two-handled goblet from which the chocolate was enjoyed. (The Library Company of Philadelphia)

Chocolate, which relies for its analeptic effect on a combination of small amounts of caffeine and larger amounts of the much weaker methylxanthine theobromine, is not as electrifying as coffee in the way these drinks are commonly prepared today. However, the early European chocolateers, like their Aztec and Maya predecessors, cooked their chocolate strong and thick. This chocolate was undoubtedly a powerful stimulant, as well as a nutritious and filling drink; we know that its flavor was strong enough to hide a variety of poisons and that it became the medium of choice through out Europe for dispatching inconvenient persons until at least the time of the French Revolution. The crumbly coarse paste from which it was prepared

contained carbohydrates and a large proportion of easily digested fats, protein, and minerals, making it an excellent concentrated high-energy food. This was the special reason that chocolate was so readily taken up by the Catholics of the time and became popular as a clerical resort during fasting. It was only later that chocolate became fashionable among the aristocracy, for whom it served, as many paintings of the period show, as a drink to accompany the start of a leisurely morning.

During most of the sixteenth century, chocolate and the stimulating effects of its caffeine remained a cherished Spanish secret. The Spanish monks enjoyed a de facto monopoly in cacao, and they busied themselves perfecting methods of roasting the beans, brought from Mexico and plantations established in the West Indies and on the African coast. They would grind and shape the hot cacao paste into rods or wafers, leaving them to dry at room temperature, and sell them to aristocratic patrons. Wherever the story of caffeine takes us, we usually find those who have taken religious vows nearby. The Jesuits widely cultivated maté in Paraguay; and the Spanish monks, who took to drinking hot chocolate regularly, became some of their own best customers and were among its most ardent promoters. Also to the Spanish clergy—in this instance, nuns serving in Mexican cloisters—seems to belong the honor of having been the first Europeans to make hard chocolate, a skill they probably learned from native American examples. These nuns are said to have made a great deal of money selling it in confections for the European aristocracy. Most Spaniards who could afford to indulge were caught up in the fad for the new drink, at a time when few other European nationals had even had an opportunity to try it or any other caffeinated product. During this period, Dutch and English raiders who captured Spanish galleons would jettison cacao beans shipped from the growing numbers of Spanish plantations in South America, for they were unaware of the crop’s value as a luxury trade item.

But caffeine secrets are hard to keep, and it was inevitable that the Spanish secret of chocolate, like the Chinese secret of tea and the Islamic secret of coffee, would soon be revealed. For one thing, by the early seventeenth century, Spain had become the center of European fashion and society, and travelers from all over the Continent assembled in Madrid to learn the latest trends. For another, the Spanish monks taught the habit of drinking hot chocolate to their visiting brothers from abroad, who took it home with them. There, among the brothers and laity, it was touted as good tasting and productive of many health benefits and was warmly received.

Atlantic

Italy was the second European nation where chocolate became popular. In 1606 Antonio Carletti returned from a visit to Spain with the latest recipe for the drink, and his countrymen quickly became avid users. By 1662 its popularity was so great that its use had become a religious issue. The Roman cardinal Brancaccio was called upon to decide whether chocolate offered so much nourishment and sensual satisfaction that its consumption during Lent was unlawful. As Pope Clement VIII had done in 1600 when ruling on coffee, Brancaccio came down on the side of chocolate, stating,

“Liq-uidum non frangit

jejunum,”

which means, “Liquids do not break the fast.”

2

This ruling confirmed a use of chocolate that had already made it a popular commodity throughout the Catholic world, for it was highly regarded for sustaining the devoted with nourishment and energy during their fasts.

3

France, the third nation to take up the chocolate craze, was introduced to the drink by Spanish Jews who settled near Bayonne in the sixteenth century;

4

however, the use of chocolate remained confined to that city, until enjoying a second, royal introduction in 1615. In that year, when each was fourteen, Anne of Austria (actually a Spanish princess) married Louis XIII, bringing in her dowry lavish gifts of cacao cakes, of the sort that would be crumbled and mixed with hot water and sugar for drinking. Thus the French court was initiated to a new luxury. Although the aristocrats embraced Anne’s gift slowly, by the time of Anne’s regency, after Louis’ death in 1643, the most coveted invitation in Paris became “to the chocolate of her Royal Highness.”

5

Cardinal de Richelieu, her husband’s tutor, credited chocolate with instilling his remarkable energy, which he applied to duties of state and by virtue of which he had secured for his sovereign the absolute power that would soon descend to the king’s son, Louis XIV (Supposedly Richelieu learned to drink chocolate from his brother Alphonse de Richelieu [1634–80], one of its earliest French adopters, who used the drink as a remedy for his ailing spleen.)

6

We do not know if the Sun King recognized this debt to the cacao bean; but it was under his rule and after his marriage to the Spanish princess Maria Theresa in 1660 that chocolate became abidingly popular among the upper classes. It remained in France, as in Spain, an expensive indulgence accessible only to the aristocracy.

Holland was modern Europe’s first republic, and, accordingly, in that country there emerged a pattern of chocolate usage different from that which prevailed in the monarchies. Once the use of the beans was understood, Dutch merchants imported them in great quantities, and the drink of the gods was available to the middle classes. After Holland won her freedom from Spain in the beginning of the seventeenth century, the Dutch began to compete with the Spanish on the lucrative sea routes. Amsterdam quickly became the most important cacao port outside of Spain. Still, today, about 20 percent of the world’s cacao beans pass through Amsterdam, and Holland is the world’s largest exporter of cacao powder, cacao butter, and chocolate.

From Amsterdam, chocolate went to Germany and Scandinavia and crossed the Alps to enter northern Italy, where the Italian chocolate masters created recipes that became popular all over the Continent. Austria imported her chocolate directly from Spain, and only in Austria did chocolate become what could be called a national drink. It may have achieved such general popularity because King Charles VI, unlike other monarchs of his day, kept tariffs on the product low. Chocolate producers in Vienna, who prepared a dozen varieties of chocolate as medicines and beverages, formed a powerful trade organization to establish their interests. An oil painting by JeanEtienne Liotarda, a Swiss painter working in Austria, called

La

Belle Chocolatière

(1743), which depicts a chambermaid bearing the artist’s breakfast drink, is the first known example of chocolate featured in the European visual arts outside of Spain.

It has been claimed, on little or no evidence, that chocolate had been introduced to England in 1520, in the reign of Henry VIII,

7

but that the drink made no progress there for more than a hundred years. The first printed mention of cacao in English occurs in

Decades W.Indies

(London, 1555) by Richard Eden (1521–76) almost half a century before either coffee or tea had been named in print: “In the steade [of money] the halfe shelles of almonds, whiche kinde of Barbarous money they [the Mexicans] caule cocoa or cacanguate.” Another early English reference occurs in 1594 in the works of Thomas Blundevil(le) (1561–1602), who specialized in writing about equestrianism: “Fruit, which the inhabitants cal[l] in their tongue, cacaco, it is like to an Almond…of it they make a certaine drinke which they love marvellous well.”

8