The Tao of Natural Breathing (16 page)

Read The Tao of Natural Breathing Online

Authors: Dennis Lewis

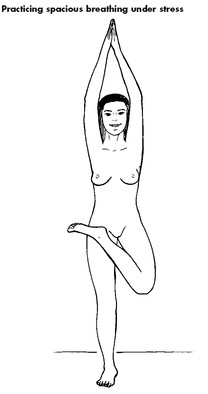

Now, staying in this posture, let your chest and belly relax, and then begin to breathe into your lower abdomen. As you inhale, sense the spaciousness filling your lower abdomen; as you exhale, sense all your tensions going out with your breath. Breathe in this way for two or three minutes; then put your tongue to the roof of your mouth and see if you can also sense the pulsation of the cerebrospinal fluid. When you finish, slowly return your arms to your sides with your palms facing down and return to the original standing position with both feet on the ground. Sense your whole body breathing. Can you notice any differences between the left and right sides? Reverse your legs and repeat the entire process.

Because it is relatively difficult, this is an excellent exercise to prepare you to practice spacious breathing in the midst of tension and stress. The key is to learn how to relax inside this difficult posture. If you find that your belly and chest stay tense, put your attention on your face, ears, and tongue, and just let them relax. Because your face most directly reflects the tensions of your self-image, it is by learning how to relax your face that you can begin to relax the rest of your body. Try breathing directly into your entire face, especially in the area of the upper tan tien. Let space permeate your nose, eyes, ears, and so on. Then return to breathing in your lower abdomen.

If you begin to lose your balance at any time during this exercise, don’t resist, don’t try to compete with gravity. Whatever happens, stay in touch with the whole sensation of yourself, including your awkwardness (your body knows how to take care of itself without the help of your self-image). If you do fall, simply try again from the beginning. As you continue working in this way—not letting yourself react in the usual way to the difficulty of the posture or to your own awkwardness—you will begin to understand that this inner sensation of yourself is intimately related to a new, more inclusive level of awareness, a level of awareness that can transform your life.

8

Spacious breathing in the ordinary conditions of life

Once you are able to keep your belly, chest, and face relaxed during the previous practice, you are ready to try spacious breathing in the ordinary conditions of your life. Whatever you do, don’t choose situations, especially at the beginning, that are so stressful that you will be doomed to failure. Start, rather, with ordinary situations—walking down the street, talking to a friend, and so on. Then, as you get a better feel of the practice in these conditions, you can move on to those that are more difficult. Eventually you will want to try spacious breathing when you are tense or emotional. Try it, for example, when you are in the middle of an argument with someone, or when you are lost in self-pity, anger, worry, impatience, and so on. If you are able to remember to practice in these more difficult conditions, you will experience firsthand how spacious breathing can help transform the stress and negativity that is bound up with your self-image into the energy you need for your own vitality and well-being.

As you undertake these practices, try them in a light, playful, and experimental way—from the standpoint of learning firsthand about yourself. As you continue this “playful” work with spacious breathing over many weeks and months, you will notice various tensions beginning to dissolve as if on their own. You will also notice your breath occupying more of each breathing space. These changes will make it possible for you to observe deep-rooted patterns of tension in the various postures and movements of your organism, patterns that inhibit the sensation of energy and movement and stand in the way of your becoming more available to the whole of yourself. You will also begin to sense that these patterns are related to, or even fueled by, various old attitudes and ideas, as well as chronic negative emotions, that create and maintain your self-image and leave little space for new experiences and perceptions. You may also observe that it is just these attitudes, ideas, and emotions that are the main obstacles to natural breathing and thus to your health and well-being.

6

THE SMILING BREATH

The “smiling breath” is for me a

fundamental practice of both self-awareness

and self-healing. The sensitive, relaxing energy field

that it produces helps me observe by contrast

the unhealthy tensions, attitudes,

and habits that undermine my health and vitality.

What’s more, the practice helps to detoxify,

energize, and regulate the various organs

and tissues of my body, and thus helps

not only to strengthen my immune system but also

to transform the very way I sense and feel myself.

Much has been written in recent years about the power of laughter to support the healing process. The story of how Norman Cousins, former editor of

The Saturday Review

, used laughter (and Vitamin C) to help recover from an incurable disease was first published in his book

Anatomy of an Illness

in 1979, and is widely known today.

45

,

45

In 1994, the California Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco, believing “that laughter is the best medicine,” added a Humor in Medicine project to its Program in Medicine and Philosophy. According to the program’s brochure,

Ways of the Healer,

“The physiological and psychological benefits of laughter have been well documented. This program addresses how to stimulate and apply healing laughter most effectively in a hospital setting.”

THE CHEMISTRY OF A SMILE

Those of us who have experienced in our own lives how laughter can alter our emotions and support our well-being, may also have observed how a genuine smile from a friend—or even from a stranger on the street—is infectious and has the power to lift our spirits and release us, at least temporarily, from the restrictions of our stress and negativity. Such a smile can transform our physiological and emotional chemistry. It can bring new energy and a fresh perspective into our lives. It can help us “re-member” and accept who we really are. Yet, strangely, very little has been written about the chemistry of the smile and its relationship to healing.

The “Inner Smile”

Given the empirical evidence we have of the extraordinary power of a smile to bring about such changes, it is astonishing that so few of us intentionally smile on our own behalf. Taoist masters have long recognized the power of the smile to help transform our attitudes and energies. And this observation led them to begin to practice what Mantak Chia calls the “inner smile.” In this practice we learn how to smile directly into our organs, tissues, and glands. “Taoist sages say that when you smile, your organs release a honey-like secretion which nourishes the whole body. When you are angry, fearful, or under stress, they produce a poisonous secretion which blocks up the energy channels, settling in the organs and causing loss of appetite, indigestion, increased blood pressure, faster heartbeat, insomnia, and negative emotions. Smiling into your organs also causes them to expand, become softer and moister and, therefore, more efficient.”

46

One finds the inner smile used in a variety of Taoist meditations and other practices, including tai chi. One also finds versions of the inner smile in Buddhist literature (for example, in books by Thich Nhat Hanh), and artistic representations of it in the budding, self-aware smile of the Buddha or the Mona Lisa.

Voluntary Smiling Can Alter Our Emotional State

It doesn’t take much observation or common sense to realize that intentionally “putting on a smile” can help change our emotional state. In his book

The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals,

Charles Darwin observed that the free expression of an emotion by outward signs serves to intensify the emotion. Writing in the late nineteenth century, the great psychologist William James laid the foundation for a more complete understanding of this subject when he pointed out that emotions are dependent on “the feeling of a bodily state.”

47

Change the bodily state or expression, and the emotions will change. More recently, Moshe Feldenkrais, one of the pioneers in physical rehabilitation and body awareness, has written that “all emotions are connected with excitations arising from the vegetative or autonomic nervous system or arising from the organs, muscles, etc. that it innervates. The arrival of such impulses to the higher centers of the central nervous system is sensed as emotion.”

48

By changing the excitations coming from these parts of ourselves through a conscious change in our movements and postures we actually change our emotions, especially those emotions that support our self-image.

One could say, and quite reasonably, that there is a big difference between “spontaneous smiling” and “voluntarily smiling.” In a recent scientific study on the effects of different kinds of smiles on regional brain activity, however, two researchers found that voluntary smiling actually changes regional brain activity in much the same way that spontaneous smiling does. In a discussion of their findings, the authors conclude: “While emotions are generally experienced as happening to the individual, our results suggest it may be possible for an individual to choose some of the physiological changes that occur during a spontaneous emotion—by simply making a facial expression.”

49

Relaxing Our Self-image and Regulating Our Organs

From the Taoist perspective, calling up a pleasant image that will bring about a smile—or even just putting a smile on one’s face regardless of how sick or negative one may feel—has an almost immediate influence on the entire organism. It opens and relaxes one’s face, which promotes openness and relaxation throughout the body. It also relaxes one’s self-image and all the emotions and attitudes that support it. This deep relaxation helps to promote the appropriate movement of blood and energy in the organism for healing, and allows the brain and nervous system to better coordinate with and regulate the viscera.