The Tao of Natural Breathing (14 page)

Read The Tao of Natural Breathing Online

Authors: Dennis Lewis

6

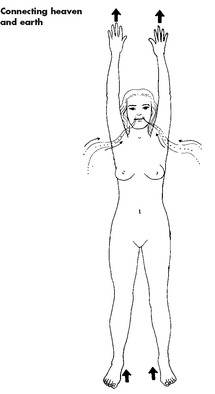

Connecting heaven and earth

Once you’ve been able to sense these movements, try the following exercise using the same basic standing position. As you inhale, slowly rise up on your toes, and simultaneously raise your arms up in front of you. Your arms should arrive straight over your head (palms facing forward) at the same time that you have reached your full extension (

Figure 27

). As you exhale, slowly lower your arms and feet until you are in the original standing position. Try this many times. Sense the upward and downward movement of energy. Sense your whole body breathing. Experience how your breath is putting you in touch with your own verticality—connecting heaven and earth both inside and outside your body. Once you’ve felt this, walk around for a few minutes and see how long you can maintain this sensation.

5

THE SPACIOUS BREATH

... each breath we take is filled

not only with the nutrients and energies

we need for life, but also with the expansive,

open quality of space. It is this quality

of spaciousness, if we allow it to enter us,

that can help us open to deeper levels

of our own being and to our own

inner powers of healing.

Thirty spokes together make a wheel for a cart.

It is the empty space in the center

of the wheel which enables it to be used.

Mold clay into a vessel;

it is the emptiness within

that creates the usefulness of the vessel.

Cut out doors and windows in a house;

it is the empty space inside

that creates the usefulness of the house.

Thus, what we have may be something substantial,

But its usefulness lies in the unoccupied, empty space.

The substance of your body is enlivened

by maintaining the part of you that is unoccupied.

39

Lao Tzu

To experience the natural healing power of breath is to experience its inherent “spaciousness.” Our breath can not only move upward and downward to help us experience our own verticality, but it can also move inward and outward to expand and connect our inner spaces with the space of the so-called outer world. In the same way that our experience of external space allows us to differentiate and relate to each other and the various objects and processes of the outer world, our experience of the internal spaces, the “chambers” of our bodies and psyches, allows us to differentiate the various functions and energies of our organism and keep them in dynamic harmony. As Chuang Tzu states:

“All things that have consciousness depend upon breath. But if they do not get their fill of breath, it is not the fault of Heaven. Heaven opens up the passages and supplies them day and night without stop. But man on the contrary blocks up the holes. The cavity of the body is a many-storied vault; the mind has its heavenly wanderings. But if the chambers are not large and roomy, then the wives and sisters will fall to quarreling. If the mind does not have its heavenly wanderings, then the six apertures of sensation will defeat each other.”

40

Clearly, for Chuang Tzu and the Taoists, the various chambers or stories of the human organism—especially the abdomen, chest, and head—need to be experienced as “large and roomy” if our various functions and energies are to work in full harmony. Without some sense of spaciousness in our organs and tissues, we are unable to feel space in the other aspects of our lives. It is just this feeling that there is no space in our lives, that there is no room to expand our experience of ourselves, that lies at the root of much of our stress and dis-ease. It is one of the main reasons we so cherish trips to the countryside or ocean, where we find not only expansive vistas of land and sky, but also profound, inexhaustible silence. Though these spacious experiences of our eyes and ears help open up our psychological structure, including our feelings and mind, the sense of spaciousness and silence quickly disappears when we return to our ordinary circumstances.

The Tibetan Buddhists also put great emphasis on the importance of space to our well-being, making clear that the “feeling of lack of space, whether on a personal, psychological level or an interpersonal, sociological level, has led to experience of confusion, conflict, imbalance, and general negativity within modern society.... But if we can begin to open our perspective and discover new dimensions of space within our immediate experiences, the anxiety and frustration which results from our sense of limitation will automatically be lessened; and we can increase our ability to relate sensitively and effectively to ourselves, to others, and to our environment.”

41

LEVELS OF SENSATION

The discovery of “new dimensions of space within our immediate experiences” lies at the foundation of health and inner growth. Because our most immediate experience is the sensation of our own body, it is here that we can most effectively begin this discovery. The sensation of the body can be experienced at many different levels, and it is just this organic experience of various levels, of various densities of sensation, that begins to give us a taste of internal spaciousness. These levels include the sensation of superficial aches and pains; the compact sensation of the weight and form of the body; the more subtle sensation of temperature, movement, and touch; the tingling sensation of the totality of the skin; the living, breathing sensation of the inner structure of the fascia, the muscles, the organs, the fluids, and the bones; and the integrative, vibratory sensation of the body’s energy centers and pathways.

But there is one more level of sensation that we are given as our birthright. This is the all-encompassing sensation of openness that lies at the heart of being. As our sensation begins to open up, as we sense a broader frequency of vibration in our experience of ourselves (a vibration that

includes

instead of excluding), we come into touch with the sensation of the energy of life itself—before it is conditioned by the rigid mental, emotional, and physical forms of the society in which we live, and, even more importantly, by our own self-image. As we learn more and more about how to allow this direct sensation of life into our experience of ourselves, we feel a growing spaciousness, a sense of wonder in which the restrictions of our self-image can begin to dissolve. It is the organic experience of this essential spaciousness that embraces the various polarities and contradictions of our lives, the various manifestations of yin and yang, and allows them to exist side by side in our being without reaction. This inner, organic embrace, this sensory acceptance of everything that we are, frees not only our body but also our mind and feelings, bringing us a new sense of vitality and wholeness.

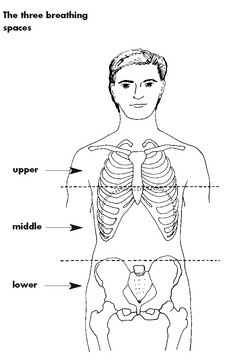

THE THREE BREATHING SPACES

To experience this inner, organic embrace, however, requires that we begin to open up the various chambers of our being, allowing them to return to their original “large and roomy” condition. The most direct way to begin this process is to learn how to experience the essential spaciousness of our breath and to guide this spaciousness consciously into ourselves—into what Ilse Middendorf calls our “three breathing spaces.” These spaces are the lower breathing space, from the navel downward; the middle space from the navel to the diaphragm; and the upper space from the diaphragm up through the head (

Figure 28

). By learning how to breathe into and experience these spaces, we begin to open to ourselves in new ways. We learn how to relax all unnecessary tension and to find dynamic relaxation, the ideal balance between tension and relaxation, in our own tissues—in the various boundaries of these spaces. And this work, in itself, can bring about many important changes both in our perception of ourselves and in our health.

The idea of the three breathing spaces coincides from an anatomical standpoint almost exactly with the concept of the “triple burner,” or “triple warmer,” in Chinese medicine. The triple burner is one of the basic systems of the body, a system with a name and a function but no specific form. It consists of an upper, middle, and lower energetic space, each of which contains within it various organs. From the standpoint of Chinese medicine, the triple burner integrates, harmonizes, and regulates the metabolic and physiologic processes of the primary organ networks. It is associated with the overall movement of chi and is also responsible for communication among the various organs of the body. It is my experience that consciously bringing the breath into each breathing space, into each burner, and sensing the spacious movement of the breath up and down through the spaces and the organs within these spaces, has a powerful balancing effect on my physical and psychological energies. If I work with this practice before I go to bed at night, it calms me and helps me sleep better; if I work with it during the day, it brings me a sense of greater relaxed vitality.

This work with the breathing spaces of the body is extremely powerful. In writing about the results of her approach to the breath through working with the various breathing spaces of the body, for example, Middendorf points out that “Through practicing and working on the breath we constantly create and experience new breathing spaces. This enables the body to free itself from its dullness and lack of liveliness, so that it feels easy and light through the continuing breathing movement and filled with new power, it feels good and more capable. This dynamic way of breathing can lead to great achievement and success in every expression of life. With its healing power it also reaches symptoms, states of exhaustion, depressions. An increasing ability to breathe will prevent these states from occurring anymore.”

42

Whatever theoretical framework we may choose for understanding our work with breath, each breath we take is filled not only with the nutrients and energies we need for life, but also with the expansive, open quality of space. It is this quality of spaciousness, if we allow it to enter us, that can help us open to deeper levels of our own being and to our own inner powers of healing. In spite of its simplicity, however, spacious breathing is not an easy practice to learn. Years of conditioning and “ignor-ance” have left us not only with many bad breathing habits, but, perhaps even more importantly, with little kinesthetic awareness of our own physical structure, and with how this structure hinders or supports our breathing. Without this inner sensation of our structure, any attempt to impose a new way of breathing—whether yogic, Taoist, or any other form—on our organism can only lead to confusion, and, potentially, further problems.