The Tao of Natural Breathing (12 page)

Read The Tao of Natural Breathing Online

Authors: Dennis Lewis

Shen Can Be Increased

A certain amount of shen is produced naturally in the organism. But given the various stresses of modern life, it is not always sufficient to keep us healthy, and it is seldom sufficient for psychological or spiritual transformation. But shen can be intentionally increased. One of the best ways to accomplish this is through conserving our basic life force, and supporting the transformation of this life force into the more subtle energy of awareness. This work depends in large part on being able to stay in touch with, to sense, the area of the lower tan tien and learning how to keep this area open and active through awareness and proper breathing. Deep abdominal breathing not only helps move our life force into the higher centers where it can be transformed, but it also helps quiet the mind and calm the brain. This is important because as science has shown, “In the adult, the rate of brain activity, measured metabolically, is ten times that of any other tissue in the body at rest. In fact, the brain burns ten times as much oxygen and produces ten times as much carbon dioxide as the rest of the body.”

34

From both the scientific and Taoist perspectives, the brain’s marathon activity influences the entire body, activating nerves, hormones, muscles, tissues, and organs. When the mind becomes quiet—when we can slow down or stop the unnecessary mental and emotional activities (such as daydreaming, criticism, self-pity, inner talking, and random associative thinking) that fill most of our day—the cells and tissues of the brain and body begin to rest and recuperate, spending less energy and storing more. This helps to increase the overall level of energy, of chi, in our organism. When chi reaches a certain level of intensity in the organism, and we are able to sense it through a quiet, ongoing awareness, transformation of more of this energy into the finer energy of shen happens naturally. This higher level of shen not only supports healing and well-being, but is also the foundation for psychospiritual growth.

PRACTICE

1

Opening your brain

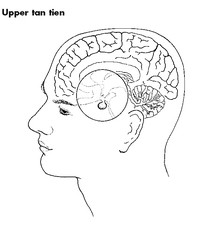

Sit or stand quietly in the usual posture, allowing your mind to become quiet and your awareness to include as much of your entire organism and its functions as possible. After 10 or 15 minutes, put your attention just below your navel and sense the energy ball expanding and contracting as you inhale and exhale. Once you feel that you are in touch with this area, allow your attention also to include the upper tan tien between your eyebrows. Sense your eyes relaxing back into their sockets. Feel the entire area around your eyes relaxing. The actual experience feels like something hard softening, or like ice melting to become water. As this melting process takes place, observe any thoughts or feelings you may be having. Don’t make an occupation out of these experiences. Let them go, and continue sensing.

2

Breathing into your brain

Once the area between your eyebrows feels soft and open, see if it is possible to inhale directly through this area into your brain, while simultaneously staying in touch with your deep abdominal breathing. See if you can feel a kind of subtle vibration, or movement, in this area. Don’t believe the negative thoughts that may arise, thoughts that will undoubtedly tell you that it is impossible to breathe into your brain. Just try it. See for yourself. Work in this way for 10 minutes or so. When you are ready to finish, bring your attention (and your breath) back to your lower tan tien. Feel that any energy you have collected is somehow being stored there. Breathe quietly in this way for a couple of minutes before stopping.

In pondering the implications of the ideas and practices put forward in this chapter, do not worry about remembering the technical terms used here. What is important is to begin to sense that your own harmonious functioning depends on a variety of specific substances (or energies) coming from both inside and outside, as well as on the movement of these substances through your breath to the places in your body where they can be stored and transformed. As you work gently over a period of weeks with the ideas and practices described in this chapter, you will begin to feel a new sense of vitality and openness, especially in your belly, solar plexus, and face. Take note of this sensation. Let it begin to spread throughout your body. Return to it as often as you can.

4

THE WHOLE-BODY BREATH

... when we are able to breathe through our whole body, sensing our verticality from head to foot, we are aligning ourselves with the natural flow of energy connecting heaven and earth.

More than 2,000 years ago, the great Taoist philosopher Chuang Tzu said that “The True Man breathes with his heels; the mass of men breathe with their throats.”

35

,

36

This ancient observation about breathing, which may be especially relevant today, lies at the heart of the Taoist approach to breath. For the Taoist, breathing, when it is natural, helps open us to the vast scales of heaven and earth—to the cosmic alchemy that takes place when the radiations of the sun interact with the substances of the earth to produce the energies of life. It is our breath, especially our “natural” breath, that enables us to absorb and transform these energies.

What is “natural” breathing? We began to answer this question in the first two chapters, when we reviewed the basic physiology of breathing and explored how to observe our breath in relation to our tissues and organs. We went deeper into the meaning of natural breathing in the third chapter, when we worked with the three primary energy centers of our body, especially the center in the area of the navel. In this chapter, we will expand the work we’ve begun to include the whole body in our breath. For it is only when our whole body breathes that we can gain the fullest access to our inner healing power—to the organic vitality that is our birthright.

A SIMPLE DEFINITION OF NATURAL BREATHING

One of the simplest, most practical definitions of natural breathing that I’ve found comes from the well-known psychiatrist Alexander Lowen, who studied with Wilhelm Reich. “Natural breathing—that is, the way a child or animal breathes—involves the whole body. Not every part is actively engaged, but every part is affected to a greater or lesser degree by respiratory waves that traverse the body. When we breathe in, the wave starts deep in the abdominal cavity and flows up to the head. When we breathe out, the wave moves from head to feet.”

37

From the point of view of this definition, most of us have little experience of natural breathing. In my healing work using Chi Nei Tsang (internal-organs chi massage), for example, many of the people I work on have, at the beginning of my treatments, little awareness of any movement in their abdominal cavity, lower ribs, and lower back. As I observe their breathing, or put my hands into their belly or on their chest, it is clear that the respiratory wave generally begins in the middle of the chest, or even higher, and seems to move only a short distance upward into the shoulders and neck. Some of these people have had abdominal surgery of some kind, and it is clear that even many years later they are still protecting themselves from feeling the pain of the surgery. Others are clearly protecting themselves from feeling painful emotions. Still others feel insecure about their sexuality. But what they all have in common is that they are unconsciously using their breathing to try to cut themselves off from feeling their physical and psychological discomforts and contradictions.

DISTINGUISHING THE OUTER AND INNER MOVEMENTS OF BREATH

To appreciate the true power of natural breathing, it is necessary to begin to distinguish two aspects of our breathing: the outer breath (the way in which our physiology operates to bring about physical respiration) and the inner breath (the subtle breath that circulates throughout our being). Whether we are working alone or being helped by someone with more experience, the key to natural breathing is through training our inner sensitivity, our inner awareness, to sense the various inner and outer movements of our breath as they take place. It is this sensitivity, and particularly its expansion into the unconscious parts of ourselves, that will enable us eventually to begin to sense the physical and emotional forces acting on our breath. It is only when we can sense these forces as they are—without any judgment or rationalization— that our breath can begin to free itself from its restrictions and engage more of the whole of ourselves.

The Outer Movements of Breath

From what we’ve said so far, it is possible to discern at least two levels of movement in our respiratory apparatus during inhalation and exhalation. During inhalation, as the air travels downward through our nose and trachea, the diaphragm also moves downward to some degree into the abdomen to make room for the lungs to expand, while the belly expands outward to make room for the diaphragm. Thus the first movement that we can sense in natural breathing is the downward movement of the diaphragm and air. As the lungs begin to fill from the bottom, however, there is also a movement of the air upward—the kind of movement that occurs when we fill a glass or a bottle—which is reinforced by a movement of the chest outward and the sternum upward, creating more room in the middle and upper part of the lungs (

Figure 21

).

During exhalation, we can sense the air moving upward and out in concert with the diaphragm, which relaxes back into its original dome-like structure pushing upward. Simultaneously, we can sense the movement of the sternum downward and the ribs and belly inward, all of which bring about an overall relaxation of the whole body downward into the earth (

Figure 22

). Thus, whether we are inhaling or exhaling, we can sense two simultaneous movements going in opposite directions. Indeed, it is through the simultaneous sensing of these opposing movements of air and tissue that we begin to develop the kinesthetic awareness—the inner sensitivity—necessary to relax our tissues and discern the movement of energy in our organism.