The Suitors (12 page)

Authors: Cecile David-Weill

Instead of making his announcement correctly, in a dignified manner, the new head butler let out a shout: “Dinner is served, Madame!”

My mother glared at me for a microsecond before saying lightly, “Girls, time to fetch your father. He must still be on the phone with Sotheby’s in New York, in the library with the Démazures.”

“Where

did

you dig up the hog caller?” said Marie sweetly as we set out on our mission.

“Watch out. I’d advise you to put a cork in it, because I could return the compliment with those brown-nosing Braissants!”

MENU

Gazpacho

Grilled Sea Bass with Fennel

Risotto with Morels

Salad and Cheeses

Crêpes Royale

Marcel and Gérard were standing at benevolent attention on the covered terrace outside the winter dining room, like parents supervising a sandbox where their children are busy playing. On tablecloths of orange and fuchsia linen strewn with white orchids, silver candelabras and crystal glassware reflected the flickering candle flames onto charger plates by César, signed with golden grooves representing the sculptor’s fingerprints. The effect was so lovely! No one else took this much trouble anymore over the décor for a dinner party, I thought proudly.

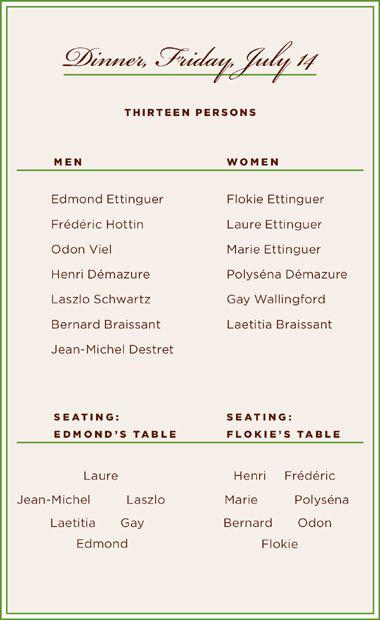

My mother called over the guests seated at her table. “Odon, Polyséna, Frédéric, Henri, Marie and Bernard, you are with me.”

“Doesn’t this remind you of school, when the teacher gathers her students on the first day of classes?” quipped Frédéric, to ease the newcomers into our protocol.

“Odon, you’re on my right; Frédéric, Marie, and Polyséna—do please stop chatting, naughty, naughty! Bernard, sit on my left. And Henri, between Marie and Frédéric.”

Inheriting those who hadn’t been summoned, my father solemnly brandished the paper on which his table seating plan had been scribbled.

“Here we all are in the same boat, cast adrift by Flokie,” he announced facetiously.

For just as my mother fulfilled her duties as hostess with the utmost devotion, my father took equally seriously his role as the class clown.

“Let’s see,” he murmured, slipping on his glasses. “But I

can’t

see a thing with these! I must have left my reading glasses in the library. Laure, dear, would you do the honors?”

“I’ve got the thumb!” Gay crowed triumphantly, having turned over her César plate to check.

“Oho! Much better than getting the finger!” Frédéric called over gaily from the other table, and the two friends exchanged fond smiles.

Jean-Michel was on my right. Without any misplaced pretensions, I naturally assumed that he would strike up a conversation with me, if for no other reason than that he had clearly been trying to bone up on the appropriate social conventions. He would thank me for his invitation to L’Agapanthe as a lead-in to some friendly or simply polite chitchat. He did nothing of the kind, however, and merely smiled at Laetitia, seated on his right. When I recovered from my surprise, it dawned on me that he had been avoiding my sister and me ever since his arrival. Of course I had noticed how he’d been all over my mother, but that was quite probably his idea of the proper courtesy due the mistress of the house. And I had the impression that flattering his “elders” was right up his alley, but so what? That was hardly a dishonorable means to achieve social success, after all. But between that and imagining that he was really trying to avoid Marie and me … His stubborn silence was suggestive, though; still, I really couldn’t see myself having such an effect on a supposedly intelligent man, so I wondered: was he nervous at the prospect of speaking to me, or simply worried that he would commit some gaffe?

Jean-Michel seemed to be studying the napkins and bread and butter plates next to the chargers by César, which we were discussing as the butler replaced them

with soup plates of marbled yellow-glazed faience from Apt. In matters of etiquette, I would have been glad to whisper advice to him, but everything in his manner indicated that he would take my kindness for condescension. Too bad! He could just wonder away. As he would surely do throughout the entire dinner.

Debating, for example, when to begin eating what was on his plate. And he would discover that unlike in the United States, where it is customary to wait for everyone to be served before picking up one’s fork, it is the mistress of the house or the most prominently seated woman at the table who gives the signal, even before all the gentlemen have been served. Sitting on my father’s right, Gay would thus be our “hostess.” The butler would then serve the men, and my father last, who might be left on short rations, moreover, for the platter sometimes offered only slim pickings by the time it reached him.

In the same way, Jean-Michel might well be perplexed by the semicircular salad plates, or the dessert plates that would presently appear with a silver-gilt fork and spoon, along with a finger bowl to be placed with its doily to the left of his dinner plate.

Too

bad for him, I thought again, and then my generous nature recovered its aplomb and made me fiddle

with my bread-and-butter plate, on my left, to show him innocently which was whose.

Laszlo, meanwhile, was grimacing as he bent down sideways and exclaimed, “Can someone enlighten me as to why mosquitoes always attack your ankles? And aren’t they unusually ferocious this year?”

“You’re telling me,” replied Jean-Michel, who started scratching in turn.

Ah, now I’ve got it, I thought, since Jean-Michel obviously had no difficulty smiling and talking with anybody but me. I then put him to one last test, handing him a small bottle of mosquito spray I’d taken from my little evening bag.

“Here, it’s my constant companion. What can I say? Mosquitoes adore me.”

Nothing. No reply. Aside from a feeble smile of thanks before using my spray.

Having no doubt observed my mounting irritation at Jean-Michel’s awkwardness or rudeness (and frankly, at this point I didn’t care which), Laszlo jumped in to rescue me from the lengthening silence. “But the worst time is at night!”

“That’s because like all insects, they don’t sleep,” observed my father, a fountain of information on all creatures great and small. “Sleep only becomes possible

when the brain has reached a certain size. Butterflies, for example, do not sleep, whereas whales, orcas, and dolphins sleep with just one brain hemisphere at a time, which allows them to swim without ever stopping.”

“Perhaps he doesn’t like me?” I wondered. But after all, that wasn’t any reason not to speak to me! Just look at that stuck-up stick Laetitia, whose hitherto unsuspected passion for nature documentaries was making my father happy to chat with her. Oh, well, as if I gave a damn! Why should I let a moron like him bother me? I decided to ignore Jean-Michel and join the conversation Gay was whipping up about Marie Antoinette.

“I’m reading a most amusing book by Caroline Weber about Marie Antoinette called

Queen of Fashion

, in which she describes how the young queen used her opinions and prejudices about dress to demonstrate her influence on the court, which she systematically challenged in the realm of fashion.”

“Isn’t that what Louis XIV had already done?” I asked.

“True, and Marie Antoinette was in fact greatly inspired by him. But she

democratized

fashion. First with her overdressed and even over-the-top style with those coiffures, the utterly insane bustles, which had such a success that she made the hairdressers and couturiers of that era rich. Then she turned fashion completely around

with the simplicity of her shepherdess period at the Petit Trianon, inventing the minimalist white muslin dress worn without a corset—which became all the rage, just like Coco Chanel’s famous little black dress did.”

“Have you read Antonia Fraser’s book?” Laszlo asked.

“No, but I did see the Coppola girl’s movie.”

“Oh, a disaster!” he replied.

“I thought it rather pretty, with all those candy colors,” I said.

“So did I,” Gay chimed in. “Everyone jumped on her. But the film wasn’t pretending to be historically accurate. And it was full of familiar faces.”

“Such as?” Laszlo prompted.

“Natasha Fraser, Antonia’s daughter; Hamish Bowles, a

Vogue

editor; the socialite Pierre Ceyleron …”

“I’m sure they’re all wonderful people, but they proved unable to save that insipid excuse for a movie. Besides,” Laszlo concluded, “I don’t think anything can top the biography by Stefan Zweig.”

Gérard began to serve the main course, sea bass grilled over fennel, and I still hadn’t exchanged a single word with Jean-Michel. Since my decision not to let that bother me, however, I had made some progress on this question. And I had understood, after trying to put myself in his place, that he was able to chat with Laszlo or my father because

he felt all of them were on the same ladder of financial and professional success, albeit at different levels. He could not, however, carry off a casual conversation or exchange with me or my sister because he was lost and had no frame of reference in our house. Wasn’t that why he’d insisted on bringing along his car and driver? To carry with him a bit of his world and a token of his success, to help him confront “the upper crust” of which Marie and I, with our pedigrees, were the incarnation? Because with us he must have felt lacking in something essential, an ease and elegance of being that requires generations to breed true.

And he was doubtless right. Not everyone has enough brio to show, as Laszlo did, that one can be a little Hungarian Jew from the gutter—as he described himself—and dazzle the most snobbish and intolerant people. Jean-Michel’s manners, for one thing, distressed me in spite of myself: his way of saying

bon appétit

; his elbows on the table; his knife and fork laid obliquely on either side of his plate, like the idle oars of a drifting boat. I could tell myself all I wanted that this wouldn’t have irritated me had I found him attractive, but I wasn’t sure it was true. Because I was conditioned by my upbringing, even though I found such conventions absurd. (As a proper Englishwoman, for example, Nanny had set our table with glasses to the right of the plate, forks placed tines up, knives with

the cutting edge facing right, and she had constantly reminded us,

Hands under the table!

Then my mother would visit us. Shifting the glasses to a position above the plate, turning the forks tines down, and the knives, cutting edge left, she would order us to keep our

Hands on the table!

)

In any case, given the simpleton sitting next to me, what did it matter? I was hardly likely to experience a soul-wrenching conflict between any personal attraction to him and the repulsion I felt for his disappointing behavior. And I had decided not to take offense at his silence, which was a small thing, after all, to one as experienced as I in making conversation and coping with the vicissitudes of formal dinners, where I had once actually seen a dinner companion fall asleep and another choke to death.

I learned the art of conversation at an early age. Mother would invite my sister and me to eat with her from time to time, for fun, as she said, although she actually had no idea what that word meant. The upshot is, now I feel capable of getting anyone at all to talk.