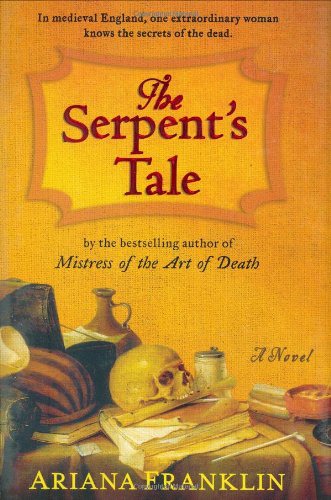

The Serpent's Tale

Read The Serpent's Tale Online

Authors: Ariana Franklin

Serpent’s Tale

Mistress of the Art of Death

City of Shadows

The

Serpent’s Tale

G. P. P

UTNAM’S

S

ONS

New York

G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

Publishers Since

1838

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi–110017, India Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices:

80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Copyright © 2008 by Ariana Franklin

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Franklin, Ariana.

The serpent’s tale / Ariana Franklin.

p. cm.

ISBN: 1-4295-5829-6

1. Women forensic pathologists—Fiction. 2. Henry II, King of England, 1133–1189—Fiction. I Title.

PR6064.O73S47 2008 2007038585

823'.914—dc22

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers and Internet addresses at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

To Dr. Mary Lynch, M.D., FRCP, FRCPI,

consultant cardiologist.

My literally heartfelt thanks.

T

he two men’s voices carried down the tunnels with reverberations that made them indistinguishable but, even so, gave the impression of a business meeting. Which it was. In a way.

An assassin was receiving orders from his client, who was, the assassin thought, making it unnecessarily difficult for himself, as such clients did.

It was always the same; they wanted to conceal their identities, and turned up so masked or muffled you could hardly hear their instructions. They didn’t want to be seen with you, which led to assignations on blasted heaths or places like this stinking cellar. They were nervous about handing over the down payment in case you stabbed them and then ran off with it.

If they only realized it, a respectable assassin like himself

had

to be trustworthy; his career depended on it. It had taken time, but Sicarius (the Latin pseudonym he’d chosen for himself ) was becoming known for excellence. Whether it was translated from the Latin as “assassin” or “dagger,” it stood for the neat removal of one’s political opponent, wife, creditor, without suspicion being provable against oneself.

Satisfied clients recommended him to others who were afflicted, though they pretended to make a joke of it: “You could use the fellow they call Sicarius,” they’d say. “He’s supposed to solve troubles like yours.”

And when pressed for information: “I don’t know, of course, but rumor has it he’s to be contacted at the Bear in Southwark.” Or Fillola’s in Rome. Or La Boule in Paris. Or at whatever inn in whichever area one was plying for trade that season.

This month, Oxford. In a cellar connected by a long tunnel to the undercroft of an inn. He’d been led to it by a masked and hooded servant—oh, really,

so

unnecessary—and pointed toward a rich red-velvet curtain strung across one corner, hiding the client behind it and contrasting vividly with the mold on the walls and the slime underfoot. Damn it, one’s boots would be

ruined.

“The…assignment will not be difficult for you?” the curtain asked. The voice behind it had given very specific instructions.

“The circumstances are unusual, my lord,” the assassin said. He always called them “my lord.” It pleased them. “I don’t usually like to leave evidence, but if that is what you require…”

“I do, but I meant spiritually,” the curtain said. “Does your conscience not worry you? Don’t you fear for your soul’s damnation?”

So they’d reached that point, had they, the moment when clients distanced their morality from his, he being the low-born dirty bastard who wielded the knife and they merely the rich bastards who ordered it.

He could have said, “It’s a living and a good one, damned or not, and better than starving to death.” He could have said, “I don’t have a conscience, I have standards, which I keep to.” He could even have said, “What about

your

soul’s damnation?”

But they paid for their rag of superiority, so he desisted. Instead, he said cheerily, “High or low, my lord. Popes, peasants, kings, varlets, ladies, children, I dispose of them all—and for the same price: seventy-five marks down and a hundred when the job’s done.” Keeping to the same tariff was part of his success.

“Children?”

The curtain was shocked.

Oh, dear, dear.

Of course

children. Children inherited. Children were obstacles to the stepfather, aunt, brother, cousin who would come into the estate once the little moppet was out of the way. And more difficult to dispose of than you’d think…

He merely said, “Perhaps you would go over the instructions again, my lord.”

Keep the client talking. Find out who he was, in case he tried to avoid the final payment. Killing those who reneged on the agreement meant tracking them down, inflicting a death that was both painfully inventive and, he hoped, a warning to future clients.

The voice behind the curtain repeated what it had already said. To be done on such and such a day, in such and such a place, by these means the death to occur in such and such a manner, this to be left, that to be taken away.

They always want precision, the assassin thought wearily. Do it this way, do it that. As if killing is a science rather than an art.

Nevertheless, in this instance, the client had planned the murder with extraordinary detail and had intimate knowledge of his victim’s comings and goings; it would be as well to comply….

So Sicarius listened carefully, not to the instructions—he’d memorized them the first time—but to the timbre of the client’s voice, noting phrases he could recognize again, waiting for a cough, a stutter that might later identify the speaker in a crowd.

While he listened, he looked around him. There was nothing to be learned from the servant who stood in the shadows, carefully shrouded in an unexceptional cloak and with his shaking hand—oh, bless him—on the hilt of a sword stuck into a belt, as if he wouldn’t be dead twenty times over before he could draw it. A pitiful safeguard, but probably the only creature the client trusted.

The location of the cellar, now…it told the assassin something, if only that the client had shown cunning in choosing it. There were three exits, one of them the long tunnel, down which he’d been guided from the inn. The other two might lead anywhere, to the castle, perhaps, or—he sniffed—to the river. The only certainty was that it was somewhere in the bowels of Oxford. And bowels, as the assassin had reason to know, having laid bare quite a few, were extensive and tortuous.

Built during the Stephen and Matilda war, of course. The assassin reflected uneasily on the tunneling that had, literally, undermined England during the thirteen years of that unfortunate and bloody fracas. The strategic jewel that was Oxford, guarding the country’s main routes south to north and east to west, where they crossed the Thames, had suffered badly. Besieged and re-besieged, people had dug like moles both to get in and to get out. One of these days, he thought—and God give it wasn’t today—the bloody place would collapse into the wormholes they’d made of its foundations.

Oxford

, he thought. A town held mainly for King Stephen and, therefore, the wrong side. Twenty years on, and its losers still heaved with resentment against Matilda’s son, Henry Plantagenet, the ultimate winner and king.

The assassin had gained a deal of information while in the area—it always paid to know who was upside with whom, and why—and he thought it possible that the client was one of those still embittered by the war and that the assignment was, therefore, political.

In which case it could be dangerous. Greed, lust, revenge: Their motives were all one to him, but political clients were usually of such high degree that they had a tendency to hide their involvement by hiring yet another murderer to kill the first,

i.e., him.

It was always wearisome and only led to more bloodletting, though never his.

Aha.

The unseen client had shifted, and for a second, no more, the tip of a boot had shown beneath the curtain hem. A boot of fine doeskin, like one’s own, and

new

, possibly recently made in Oxford—again, like one’s own.

A round of the local boot makers was called for.

“We are agreed, then?” the curtain asked.

“We are agreed, my lord.”

“Seventy-five marks, you say?”

“In gold, if you please, my lord,” the assassin said, still cheerful. “And similarly with the hundred when the job’s done.”

“Very well,” the client said, and told his servant to hand over the purse containing the fee.

And in doing so made a mistake which neither he nor the servant noticed but which the assassin found informative. “Give Master Sicarius the purse, my son,” the client said.

In fact, the clink of gold from the purse as it passed was hardly less satisfactory than that the assassin now knew his client’s occupation.

And was surprised.