The Secret of Kells (9 page)

Read The Secret of Kells Online

Authors: Eithne Massey

Brendan and Aidan began to gather the pages of

the Book. They were scattered all over the clearing. A page was caught up in a gust of wind and blown into the trees, and Brendan ran after it. As he scrabbled in the grass to pick it up, he heard Pangur give a happy miaow, and when he looked up he found he was looking directly into the eyes of a large white wolf. It sat very still, gazing at Brendan. Its eyes were a vivid green. For a moment, there was absolute quiet in the forest. Brendan stared at the wolf and the wolf stared back. Then, the wolf stood up and slowly walked over to where a page of the Book lay on the ground. Very gently, it placed its nose on the page and edged it towards Brendan.

As he looked deep into those green eyes, Brendan knew exactly who the wolf was.

‘Aisling,’ he whispered. ‘It is you, isn’t it?’

The corners of the wolf’s mouth lifted. Then, with one last look, it turned and raced into the darkness of the trees. The moon came from behind a cloud showing nothing, not even a trail of footprints in the snow.

Brendan made his way back to Aidan. They put the scattered pages back into the satchel with the

Eye, and, sure that they were safe from further attack as long as they were in the forest, Brendan gathered branches and built a fire. Aidan slept, but although Brendan was exhausted, he sat for a while watching the flames and the moonlight. He found that tears were streaming down his face. He cried for the brothers, for Tang and Assoua and Leonardo, but mostly he cried for his uncle. All his anger with Cellach was gone. The Abbot had only wanted what he thought was best for Brendan and for Kells. He had only wanted to protect him. Brendan remembered his uncle’s kindness. He remembered his goodness. He remembered the gentleness that had been hidden by the stern manner. Now he was dead, and Kells was destroyed, and all his uncle’s work seemed to have been for nothing.

‘Not for nothing,’ Brendan whispered fiercely himself. ‘I will finish the Book. I will do it for him.’

W

hen Brendan opened his eyes the next morning, Aidan was up and about. The old monk was bruised but not badly hurt from his encounter with the Northmen the evening before. Determined to keep their spirits up, he said cheerily, ‘Well, lad, the sun is up. Time to be stirring and on the road.’

‘Do you think we could look for some food first?’ said Brendan. ‘I’m starving.’

Aidan said, ‘You know, it looks like there is something, or someone, looking after us. It wouldn’t happen to be your friend from the forest?’

He nodded to a pile of nuts and berries, and some wizened winter apples. A small clump of snowdrops grew beside it. Brendan bent down and gently touched the flowers.

After they had eaten, Brendan said, ‘Where will we go, Aidan? What will we do?’

Aidan sighed. ‘I don’t think we should try to go to another monastery. Places that were once beacons of learning and peace have become the targets of the Northmen’s greed. For the moment anyway, we should find a place where we can do our work in secret. There’s more than one way of being a monk, you know. The Abbot’s way was one way, and a very good way. But being part of a big group of brothers, and surrounded by all the organisation and the business of Kells is not the only way to serve God. There are many men and women who go down a different path. Saint Kevin, for example, he lived alone in the wilderness and in the wilderness he found God. Though I always think it might have suited him to have lived alone even if he hadn’t been a monk and a great saint. He was a bit of a cranky character, you know – he threw a woman in a lake once because she was annoying him.’

For the first time since the Northmen’s raid, Brendan found himself close to smiling.

‘You will have to tell me his story, Aidan. But is

that what we should do? Live in the wild?’

‘We’ll see where the road takes us,’ said Aidan. ‘I think we will know the place we should stay in when we see it. What do you say, Pangur?’

Pangur miaowed happily, and led the way through the trees.

For as long as they travelled through the forest they would find stashes of food left for them every morning, nuts and berries and fruit. The food seemed to give them more strength than ordinary food. This was a very good thing, as the journey was difficult. The snow continued to fall and the nights were icy cold. As they walked, Aidan told Brendan his stories of saints and ancient heroes and magical beings. When he thought Brendan was ready to listen, he also told him about the things the Northmen believed, about their gods and their great sagas. He told Brendan how the Northmen believed that the gods had created the first two humans from two trees. He told him stories of Baldur the Brave, of the beautiful goddess Freya and mischievous god Loki. Brendan was amazed to hear that the Northmen told stories

about a great serpent who lived deep in the earth and about a god who sacrificed himself for the good of his people: Odin the One-Eyed, who had hung for three days upside down on a tree in order to find wisdom. Even still, the Northmen thought that one might meet Odin on the road, a hooded, one-eyed traveller with two ravens on his shoulder. They were called Hugin and Munin, Thought and Memory. And as Aidan told his tales, they walked further and further from Kells. The snow melted and the wind grew warmer. Spring came back to the forest.

They travelled south and west, away from the path of the Northmen. They had many adventures on their travels. Most of the people they met were kind to them, and gave them food and shelter. All of them wanted to hear the story of how they had escaped from the Northmen.

Finally, one day, as they walked through mist and rain up a mountain that seemed never ending, Aidan suddenly grabbed Brendan’s arm and forced him to come to an abrupt standstill. The mist slowly cleared and they found themselves

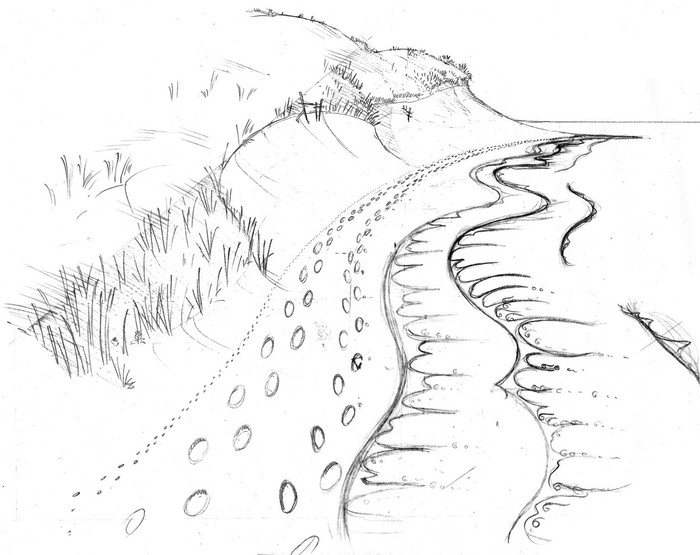

standing at the very edge of a rocky cliff. The path ahead of them ended in air, and they were looking down into the most beautiful green valley, bounded on the far side by the arc of a rainbow. A waterfall fell down from the heights of the hills to the valley floor, and formed a lake at the bottom. From the lake flowed a curving silver river. On the eastern edge of this river there grew a small oak wood. To the south and west, the valley opened out. And there, where the land sloped down towards the water’s edge, was the sea. The river flowed into the bay just where a curve of golden beach met the blue water. The sun was beginning to go down over the water and Brendan thought he had never seen anything so beautiful as the light dancing on the waves.

He looked at Aidan and Aidan looked at him. Brendan nodded. ‘It’s here, isn’t it?’ he said.

The three of them made their way slowly and carefully into the valley, and slept that night in the shelter of the oak wood.

The next day Brendan wanted to start gathering berries for ink.

Aidan said, ‘No, first things first. We have to build a proper shelter. A bothy in the trees is all very well for the summer, but the winter will be back soon and the wind and the rain will come at us from the west. We have to be prepared for that. We have to build well. And as your uncle knew, the best buildings are made of stone.’

Brendan groaned. ‘And you are beginning to sound like him. I thought that after I left Kells I would never, ever again have to drag stones around.’

Aidan laughed. ‘Never say never. Ah, come on, lad. It won’t take that long; we are just going to build the basics. Two little cells, that’s all we need.’

So through the summer days they worked, and built two small stone huts to Aidan’s design. They were round and windowless, and reminded Brendan of the beehives he had looked after in Kells. They also planted vegetables and herbs, and they gathered berries and made new ink. They searched for fallen feathers in the forest, and from these they made pens. And by the time autumn came, Brendan was able to begin work on the Book. While he worked, Aidan talked to him,

advised him, and told him more stories. The valley was very quiet. Sometimes a hunter or a fisherman would come upon them, and they would feed their visitor and ask for news of the outside world.

One day a wild-looking man with a very hairy face arrived in the valley and asked Aidan to hear his confession. Aidan was very quiet and serious after their conversation. Brendan realised why when he saw the strange man baying at the moon that night.

‘He’s a werewolf, isn’t he?’ he whispered to Aidan.

Aidan nodded. ‘He is. He’s a Kilkenny man, and they are desperately prone to it. But he is a good man. You know St Ronan was a werewolf too, or at least his wife said he was. She used to complain that she could never get a decent night’s sleep because of the racket he made when the moon was full.’

Sometimes they themselves would make a journey out of their forest in the valley and visit one of the tiny villages nearby. They were always made welcome. Aidan became famous as a storyteller and the children, especially, loved to

hear his tales.

They built a currach and would fish on the lake or out to sea. On clear, warm evenings they would go to the cliffs, at the edge of the coast, and look to the west as the sun set over the ocean. They often went walking on the long beaches along the shore, following the line at the edge of the water, where the sand met the sea and the sun made everything shine silver and gold. Aidan would smile into the setting sun and tell Brendan of his dreams of going further west.

‘Like your namesake, Brendan, the Great Navigator. Did I ever tell you the story of how he landed on a whale and thought it was an island? Ah, I did. I must have told you every story I know by now. But, you know, no one really knows what is out there, out to the west. You might reach the edge of the world and fall off, into God knows what. It would be a marvellous thing to see the place where the sun goes down.’

He paused. ‘Brendan, I have a favour to ask you. When I go, and you know I will have to go sooner or later, I want you to put me into a boat and send me westwards, into the setting sun.’

‘You’re not going anywhere,’ Brendan would say. ‘You are staying here with me and Pangur.’

‘Ah Brendan, don’t be upset that I’m talking to you like this. The line between life and death is a narrow one, you know. It is no more constant than that line where the tide meets the sand.’

All through this time, Brendan worked on illustrating the Book. He tried to put everything he knew into it. Everything he had felt in his heart and thought with his head. The sounds and smells of the forest; the feeling of the green moss on the tree under his hand. And he put in all those he had loved.

He put in Aisling, now as a white-haired angel, now as a wolf, now as a white bird with a human face, now as a twisting of pale flowers in a margin. He put in the Abbot, with his sad stern face and his tall figure. Cellach had a Book in his hand, open, finally taking the time to look inside. He put in each of the lost brothers: Leonardo, Assoua, Friedrich and Jacques. They peered out at him from under the tall letters and bands of colour. He put in Assoua’s lions, although he found he could

not remember the description all that well, and when he looked at what he had drawn, he was not sure it was exactly right. He put in the otter he had seen in the forest, with the fish in its mouth; he put in the eagles he had seen flying over the high mountains they had crossed on their way to their valley. He put in the shy deer and the clever foxes; the mice that had kept him company in his cell and the robin that had looked on as he learned to draw. He put in the moths he had seen flitting in the light between the trees. He even put in the monster, Crom Dubh. It became a green serpent that wriggled and curled through the borders, swallowing its own tail. He put in the spiral path in the forest, the path that had led him to knowledge and wisdom. And again and again, he drew the tree of life. Every time he drew it, it was different and more wonderful, as if the drawings themselves were growing like trees, as he himself had grown. And when Pangur played with her kittens, he put them in too. He drew them as they crawled over her back and played tag under her legs.