The Secret of Kells (6 page)

Read The Secret of Kells Online

Authors: Eithne Massey

B

rendan looked around him. The cell was damp and bare. There was very little furniture: just a wooden table, a three-legged stool, and a straw pallet to sleep on. There wasn’t even a fireplace. Brendan’s only company appeared to be a nest of baby mice and a very busy spider, intent on creating a web between the rafters. Brendan examined every corner, but he could not find any way out of the cell. Faint light came in from a tiny barred window high up on one wall. He pulled over the stool and climbed onto it, peering out. The window looked out at ground level so all he could see were the monks’ feet passing by. They had started the day’s work on the wall. Brendan recognised Brother Jacques’s bony toes and called out to him, but he did not stop. All the monks knew that the Abbot was in a terrible mood today and were going about their tasks as quickly as possible.

Watching the passing feet, the mouse family and the spider and wondering how he could get out was Brendan’s only entertainment all day. In the evening, Brother Tang came to the door with a meal of soup and oatcakes and buttermilk for him. Tang was sympathetic, but said to Brendan, ‘It’s more than my life is worth to let you out, my child. The Abbot is like a demon today. He is pushing himself – and all of us – to work on the wall as if there were no tomorrow. I’m telling you, he will end up killing himself if he keeps going like this. And he has had a dreadful row with Brother Aidan. We have never seen anything like it in Kells. He tried to take the Book from him! But Brother Aidan just spoke very quietly and said to Abbot Cellach that the Book had been put in his keeping. That minding it was a sacred task given to him by the dead brothers of Iona. So in the end Abbot Cellach left it with him. But he told Aidan he would have to leave Kells when the first thaw of spring comes.’

‘Leave Kells?’ said Brendan. ‘But where will he go to be safe? And he can’t leave here. We have to finish the Book.’

Tang sighed. ‘Yes, what are we going to do about the Book? All of the brothers want to see it finished. That is why many of us came to Kells, you know. Because it was known as a place of great learning and a centre of illumination. We had heard of the marvellous work that was being done and we wanted to be part of it. And now we have ended up as stonemasons and builders. But there, I have said too much. It is not for me to question the Abbot’s will. Eat up your dinner now. I’ll be with you in the morning with some breakfast. And Brendan, try not to look so sad.’

He turned to go, and then turned back to Brendan and asked him, ‘By the way, is Brother Aidan’s cat with you? She’s been missing all day and he’s very worried about her.’

‘No, I haven’t seen her since I was locked up,’ said Brendan, wondering what Pangur was up to.

Brendan couldn’t eat his dinner, even though he realised that Brother Leonardo had tried to make it especially nice for him. The food stuck in his throat so he fed the oatcakes to the mice.

I have to do something, he thought. I have to go

to the forest and get Crom Cruach’s Eye so the Chi Ro page can be written … But here I am stuck inside these walls with no way out.

He felt angry tears come to his eyes. Why couldn’t he make the Abbot see how important it was to finish the Book? How important it was to give people hope? To let them know that the times of beauty and peace would return? To reassure them that there was more to life than terror and darkness?

He lay huddled in the dusk, listening to the voices of the monks singing in the church, and later still to the sound of a blackbird singing from the forest. And when darkness fell and the moon rose, shedding its pale light through his little barred window, he heard a strange noise. He started up and went to the window, where he climbed up to the bars to peer out. What could it be? Listening carefully, he could make out that the voice was calling his name, and something white had appeared at the grating. In fact, two white things appeared: one was Pangur Bán, looking very proud of herself, and the other was Aisling, looking pale. She was not at all happy to be inside

the walls of the monastery.

‘Hello, Brendan,’ she said. ‘Happy to see us?’

‘You could say that!’ said Brendan, grinning from ear to ear with delight. ‘But how did you find me? How did you know I was here?’

‘Pangur was very brave,’ said Aisling, stroking the cat, who purred loudly. ‘She came to find me in the forest, to let me know you were in trouble and needed help. Now, how can I get you out?’

Brendan sighed heavily. ‘The door of the cell is locked and bolted from the outside, and the Abbot has the key of the tower. He keeps it in his bedroom, hanging up on the wall. And he sleeps at the top of the tower. He has shutters on the window so the moon won’t keep him awake. And he is a very light sleeper. He wakes up at even the slightest noise; you would have to be as quiet as a mouse or as quiet as Pangur here, to get the key. Maybe you should get Aidan? Maybe he could help?’

Aisling shivered and then said something very strange, ‘I’m sorry, Brendan. I couldn’t do that. For a start, most likely Aidan would not even be able to see me. But I have another idea. Stay where you

are. I won’t be long.’

‘Don’t worry, I won’t be going anywhere,’ said Brendan gloomily. He peered after Aisling and saw her leap lightly away. Then she came back and picked Pangur up. Just before she disappeared, with Pangur clasped in her arms, she turned to Brendan and said, ‘The Abbot has shut out the moon, but he can’t shut out the mist.’

Brendan sat by his window in the moonlight, waiting for Aisling and Pangur to return. Despite himself, his eyes began to close, and from far away it seemed to him as if he could hear the sound of singing. The singing crept into his mind, winding through it like a trail of ivy, opening pictures in his head. He could see Aisling and Pangur as they made their way to where the Abbot slept in his tower, Aisling gliding up the stone wall with Pangur clasped around her neck. There, through the gap in the shutters, he could see his uncle lying fast asleep. He was snoring a little and he had a frown on his face. On the wall beside him hung a large key. Aisling began to sing softly to the cat.

You must go where I cannot

Pangur Bán, Pangur Bán

Níl sa saol seo ach ceo

is ní bheimíd beo

ach seal beag gearr.

As she sang, a mist grew and swirled around Pangur. The cat seemed to lose her solid, furry form and became a creature of mist and shadows.

And the mist cat made her way through the gap in the shutters. As the cat took the key from its place on the wall, the Abbot moaned gently in his sleep. Brendan stirred in his dream state, afraid that his uncle would wake up. But the Abbot only muttered something about a wall and Pangur came back to Aisling, the key held safe in her mouth.

The music continued, but then another noise jerked Brendan out of his dream. It was the noise of a latch being lifted. And there was the mist Pangur, with the key of the tower in her mouth. Brendan let himself out quickly and made his way past the sleeping monastery. The mist-cat slid away back to the tower where she replaced the key

beside the sleeping abbot.

When Brendan reached the secret entrance in the wall, he found that Aisling was waiting for him on the other side.

Brendan was so delighted to be out of the tower that he gave Aisling a hug.

‘Hug Pangur if you like,’ said Aisling. ‘She’s the one who did the work. But listen, why did the Abbot lock you up?’

‘Because I disobeyed him. He caught me trying to go to the forest.’

‘Why? To come to see me?’

‘Not just that,’ said Brendan. ‘I wanted to go into the forest to find this.’

He raised his hand, and Aisling leapt backwards in fear.

‘The Eye of Crom!’

‘That’s what it looks like, doesn’t it?’ said Brendan. ‘But it is actually a crystal. There was once another crystal just like it. Colmcille used it to make the most beautiful drawings in the world. It was lost on Aidan’s journey to Kells, and he says we need another one. We can’t finish the Book without it. I think there is one in the Dark One’s

cave. I have to go there.’

Aisling sat down suddenly on the ground, as if her legs had given way from under her.

‘Fight Crom Cruach! You cannot do that! You cannot go there! The monster kills everything it touches!’

‘I have to, Aisling’, said Brendan. ‘I have to try, at least.’

‘No, Brendan, you don’t understand,’ said Aisling. ‘Crom Cruach took my people. It took my mother. It is all-powerful. Even your saints, Colmcille and Patrick, could not kill it; they could only send it deeper into hiding. It is the thing that crouches and waits in the darkness, which lies there forever, waiting to strike. It is Crom Cruach, Crom Dubh, the Black Crooked thing. You are only a little boy. You couldn’t even climb a tree before I showed you how. You have not much strength and you have no magic. Please, don’t even try to do this.’

Brendan’s looked into Aisling’s pleading face. He felt a pain in this chest as he thought of his own mother. He was sorry to upset Aisling, but he knew what he had to do.

‘If we do not get the crystal, the Book will never be finished. Aidan told me that the crystal lets you see things you would never be able to see with just your own eyes. Imagine, being able to see the pattern on a greenfly’s wing or the veins on a blade of grass. I want to bring all those things to the Book, so that others can see it; and this is the only way to do it. You don’t have to come with me. Maybe it is better if you don’t. I don’t want you to get hurt. But if you don’t, I will still have to try to do it alone. I have to do it for the Book.’

They sat in silence for a moment. Aisling was crying, and Pangur was trying to lick the tears from her face, winding around her, comforting her with loud purring.

At last, Aisling pushed her long hair back from her face and said, ‘Alright then. I will help you. I will do it for you, and I will do it for the Book. And I will do it for my forest, because it will never be free of fear as long as Crom Cruach lies waiting underground at the heart of the wood.’

But her face had a frightened look that made her seem not like a little girl but someone much, much older.

T

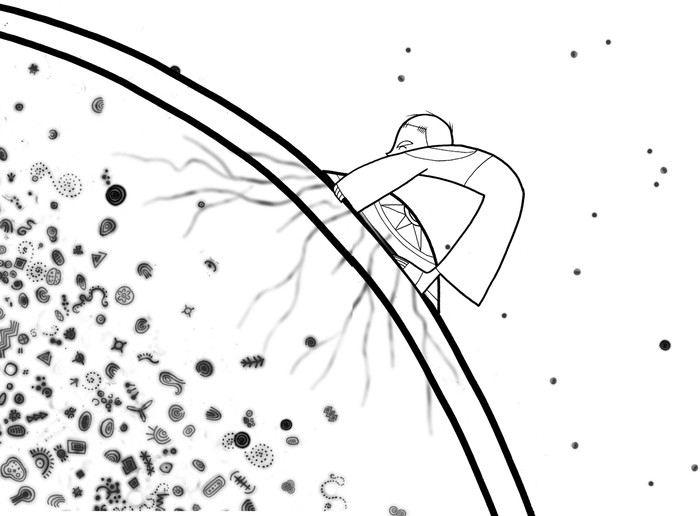

he forest seemed a very different place in the nighttime. The darkness drained it of colour. The shapes of the trees stood out sharply, like black charcoal lines against the brighter sky. A fox cried, its head up, and crows swooped through the gloom, their outline clear against the full moon. Aisling led the way and they moved deeper and deeper into the shadows, away from the moon’s brightness. As they went further into the wood, it grew colder, unnaturally cold. Pangur kept close by them, paying no attention to the rustling noises of small animals, the mice and hedgehogs going about their nightly business in the undergrowth.

Finally, they reached the clearing with the cave mouth and the stone figures. Brendan shivered when he saw the entrance stones, carved with the eye pattern that he now had on his palm. One of the stone figures was still upright; the other lay on the ground where Aisling had pushed it down. It

still blocked the entrance to the cave, and through the summer, vegetation had grown over it. Not ordinary vegetation, not the nettles and briars and long grass that grew everywhere else in the forest, but something dark and slimy and foul-smelling, as if the darkness from under the earth was trying to creep out. Here even the moonlight had a greenish tinge; not the bright fresh green of the forest but a murky green, as if something had begun to rot. There was a smell too, a smell that reminded Brendan of hot days in Leonardo’s kitchen when meat had begun to go off. But it was not hot; it was horribly cold and still.

‘No life,’ whispered Aisling. ‘No life.’

Pangur leapt into her arms and snuggled down there as if she wanted to be somewhere else entirely.

For a moment, fear gripped Brendan. Was this really the only way to find a crystal like Colmcille’s? Wasn’t he crazy to try to fight a monster that great and saintly warriors had not managed to destroy? As Aisling had said, he was only a little boy. Surely there was no point in trying to do something that was this hopeless? Then he

remembered something. The Abbot had once told him the story of how his parents and all his people had fought the Northmen. It was hopeless, but they had continued to fight. And maybe that was how the invaders had missed finding him. Maybe that was how he had survived. Now it was his turn to do something that seemed hopeless. There was no other way to go but forward – into the darkness of the cave.

He looked back at Aisling. She had set Pangur down. Her face was grey; her eyes huge; her body slumped like an old woman’s. She was shivering uncontrollably.

Brendan ran back to her and wrapped his cloak around her shoulders.

‘Aisling, you must go back,’ he said. ‘This place is hurting you. I’ll go on alone. Bring Pangur with you, she’s terrified.’

But Aisling shook her head. ‘I must help you,’ she said.

She went over to where the stone blocked the entrance and began to push. Brendan ran to help her. But before he could reach her, she had used every last inch of her strength to raise the figure

upright so that the entrance to the cave was open again. And just as she finished, the wind started.

It was the wind that had tried to suck Brendan in once before. He was being pulled forward. He could see that beside him Aisling was also being pulled into the darkness, although she was resisting with all her strength. His cloak was blowing about her shoulders, and her hair was the one spot of brightness in the blackness all around.

He tried to run towards her to help her, but then she faded into wisps of mist and moonlight, and now he himself was being pulled into the cave’s mouth … It seemed to Brendan that he was being buffeted and blown like a feather in the centre of a dark whirlwind. He was being pulled further and further in, falling down into blackness.

Then the wind stopped. Brendan was standing on dark stone deep inside the cave. He held up his torch. The walls around him were lit by a faint green glow. The dreadful smell that had filled the clearing was much stronger here. It smelled as if dead bodies had lain here for a long, long time.

Brendan tried to keep from swallowing the foul air into his lungs and looked around him. There

were strange designs painted and carved on the walls of the cave. The patterns were not unlike the spirals and circles, the lozenges and triskels and interlacings that were part of the patterns Brendan had seen, and indeed helped to draw, in the Book. But here the message they carried was not one of goodness and hope. Here they meant something evil. He could feel it coming out of the walls. There were bones scattered around the cave too. He did not look too closely at them as he had a horrible feeling that some of them might belong to humans.

There was one pattern, one image that was bigger and more vivid than any of the others. It lay at the centre of the maze of patterned walls. It was a bright livid green, the green of frogspawn and lichen. No, not frogspawn. More like the skin of some huge serpent, coiled around the walls of the cave. Each scale was so delicately etched that it seemed almost lifelike.

Brendan felt his head begin to spin. Was it Crom Cruach’s body, curled around the inside of the cave? If only, he thought, I had at least brought a weapon with me, a knife from the kitchen or a stick from the forest.

At his feet a crack opened and Brendan was falling again, through swirls and spirals of pattern. It felt to him as if he had moved into some other dimension, where he was falling through water rather than air.

Yet it was not real water, because he could breathe in it with difficulty. He tried to swim upwards through the blackness. He looked at the shape on his hand; it was glowing, like a torch in the darkness, and now it showed the serpent Crom. His eye followed the length of the coiled serpent to the small, evil head. Its eyelid was closed as if it was sleeping. The head moved up slowly, sniffing the wind; the red, forked tongue flickered out of the great mouth. The head turned slightly. Was raised up. The creature had scented him. Scented his fear. Its eye opened, a glistening crystal, a shining focus of white fire. The creature twisted and coiled around the walls, encircling Brendan on all sides. He lashed out with his hands.

As Brendan looked into the eye it seemed to mesmerise him, draw him into its depths. He forced himself to turn his head away from it. But

as he did, his heart nearly stopped. He felt something at his legs, and he realised that the green and silver coils were moving, wrapping themselves around his feet and flicking him into the air, like a cat playing with a mouse.

Brendan’s blood was beating in his head, like some kind of wild and frightening music, as he was buffeted and thrown through the darkness. A piece of chalk fell out of his pocket, and he grasped it in his hand.

From somewhere Aidan’s voice came, as if Brendan were back in the Scriptorium and his friend was urging him to let his mind go free:

‘Use your imagination, lad, your imagination can do anything, can go anywhere. Let it free. There’s something holding you back from letting it go. Unless you turn around and look at what that is, you will never be free of it …’

And suddenly Brendan was in the forest, surrounded by the green leaves of summer, and he could hear Aisling whispering to him:

‘Look at the leaves, Brendan, look at how the green shoots fight their way through the rock. The leaves are so weak, Brendan and the rock is so

hard. But the flowers and the leaves come back every year, even through the stone. They are the strong ones … they come back. You can be as strong as a leaf, as brave as a blade of grass. You must turn the darkness into light!’

And then, most surprisingly of all, he was in the Cellach’s study and he could hear the Abbot’s voice:

‘You know there will come a day when it will be up to you, Brendan, to do what has to be done. There will be no one else to do it.’

He took hold of those three things: the power of the imagination and the hope of the forest and the strength that comes to those who take up the hopeless task because there is no one else to do it. And he found that he was not unarmed after all. He began to do the only thing he could think of doing; he began to draw.

Frantically, as Crom Cruach writhed and coiled, Brendan took the chalk and drew lines and circles around the serpent, caging it in. With each line he drew, the monster became more and more enraged. Brendan turned and twisted, wriggling as the serpent tried to wrap its coils tighter around

his body. He realised that he could look the monster in the eye, the shining crystal that shone out in the midst of all the darkness of the cave.

As Brendan twisted and turned the chalk flew out of his hand and fell down into the black space. It was then Brendan discovered he had been pulled so close to the shining eye that he could reach up and grab it. He took the monster’s eye with both his hands, forcing his fingers into the slime under the lids. The evil head started to fling itself backwards and forwards, trying to escape Brendan’s grip. It was doing its best to strike him with its poisoned tongue. Brendan held on. He held on and pulled as hard as he could.

The monster flung him backwards and forwards with all the power of its body. It was hissing so that great clouds of foul black steam came from its mouth. Brendan knew that he could not keep his grip any longer. But that he had to. He could feel the eye burning his hands as he pulled, as if it were made of fire. In spite of the pain and the terror that gripped him, he did not let go.

As the eye came loose, the monster writhed in agony, coiling itself tighter around Brendan, seeking to crush his bones. It howled a fearful noise that made the rock walls of the cave shudder. And finally, with a roar of pain from the serpent and of shock from Brendan, the eye came out from the socket. Red gore dripped and hissed as it dropped into Brendan’s arms, but the eye itself was as hard and bright as a diamond.

Brendan had done it. He had pulled the eye from the monster’s head.

He fell back, watching in horror as the monster twisted madly. Blind now, it groped in the darkness with its head, trying to find Brendan so that it could catch him in its mouth. But as Brendan watched, the serpent, maddened with pain and rage, caught up its own tail and began to swallow itself, mistaking its own flesh for that of Brendan’s. And so it swallowed frantically and continued to swallow and swallow, until it finally stopped. There was nothing left of Crom Cruach except a green circle of scales and mouth. The monster had destroyed itself. Brendan blacked out.

When he came to, he was at the mouth of the cave. Brendan wondered if he had simply dreamed

the terrible battle. And yet the crystal was in his hand, caught in the blaze of dawn sunlight that lit up the clearing and made it a place of beauty rather than horror. The black leaves had gone from the trees. The grass of the clearing was covered in small white flowers.

‘Aisling!’ Brendan called anxiously, looking around him in an attempt to find her. There was no sign of the little girl. But there was a sign from her. Where Aisling had fallen there was a carpet of white snowdrops on the green grass, and lying on it was his cloak. On the cloak, there was a single white flower.

Pangur and Brendan looked at each other. Silently, the boy and the small white cat started to make their way back to the monastery. The sun was rising, lighting up the sky into red and gold and pink, and all the colours of the late summer forest seemed to be celebrating the defeat of Crom Cruach, the dark one who had kept the forest in a cage of fear for so many long years.