The Secret of Kells (5 page)

Read The Secret of Kells Online

Authors: Eithne Massey

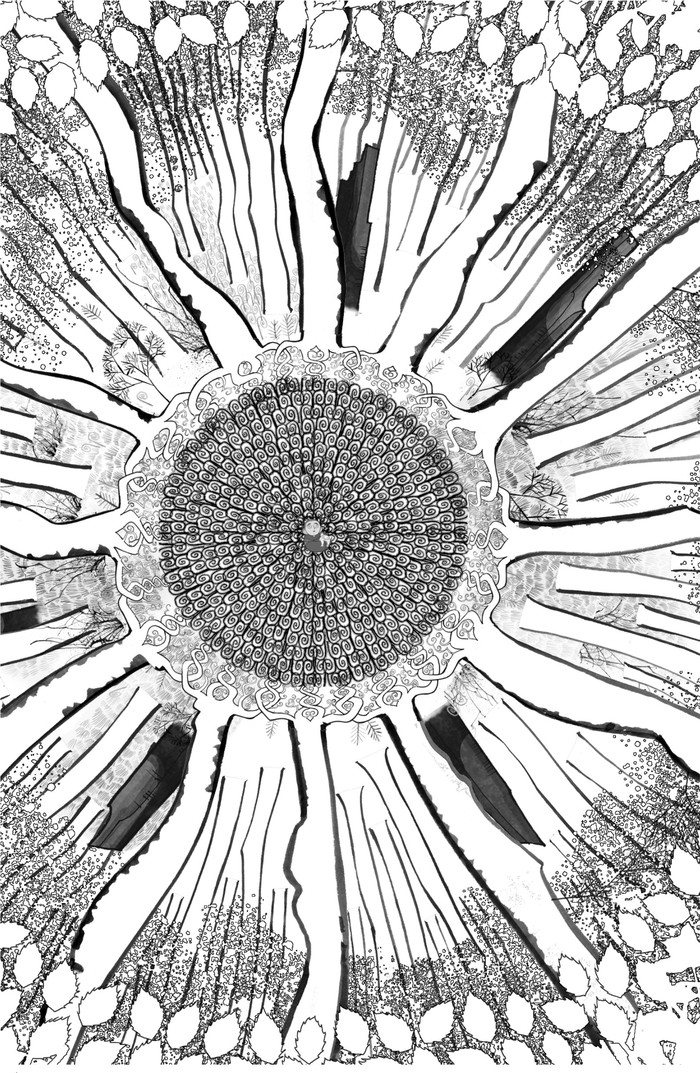

Aidan taught Brendan other things too, how to hold the pen steady and straight, how to touch the page as lightly as a bee’s wing. He taught him how to draw the fabulous interlacings that decorated the Book. How every stroke was to be done for the love and glory of God and nature. He made Brendan realise that a line drawn well was as much an act of worship as building an abbey or saying a prayer. Sometimes Brendan made mistakes and felt tempted to give up, but Aidan always encouraged him to keep going.

While they worked, Aidan told Brendan stories of the saints. He told him about Patrick, the first of the great saints of Ireland, who had turned himself and his monks into deer in order to escape the attack of an angry king. He told him of Brigid, who used a sunbeam as a coathanger and whose symbol was the February snowdrop. He told him of Ailbhe, whose foster mother was a wolf, and who had invited her to dinner every day in his palace when he had become a great and powerful

bishop. Brendan especially liked that one because of the wolf. He also loved Aidan’s story about a French saint, called Austreberthe, who asked a wolf to carry the laundry for her convent, as he had eaten the donkey that used to do it for her. But Brendan’s favourite story was the tale of Colmcille’s horse.

When the saint was very old, his beautiful white horse, who had grown old with him, came to him one day and laid his head on his chest. And the horse had wept, because he knew that Colmcille was going to die soon. The other monks had wanted to send it away, but Colmcille had not let them, for he loved the animal very much. And also because it comforted him that the horse had realised something that even Colmcille’s best friends in the monastery did not know.

But Aidan also told Brendan stories that were not about monks or saints. Stories about the magical beings who had lived in Ireland before the coming of Christianity. He told him how many of them had come and spoken to the saints about the glorious days gone by. About Oisín, child of the deer and son of Fionn, and the Swan Children of

Lir, and about Lí Ban the mermaid, who had changed shape when the waters of Lough Neagh rose up and covered her kingdom. And because Aidan had studied Greek and Latin, some of the stories he told were wonderful tales about people who lived far away from Ireland.

Brendan once asked Aidan, ‘But were they real people? Did those things really happen? My uncle says those are only imaginary things.’

And Aidan answered, ‘Does he indeed?’ Then he sighed. ‘Your uncle is a very wise man, Brendan, but no more than anyone else in this world, he doesn’t know everything. There are those that might say the faith that we believe in is no more than a story, and miracles a different sort of magic. But I have been here on this earth a long time now, Brendan, and there is something I am sure of. Just because you can see something doesn’t mean it is real. And just because you cannot see something doesn’t mean it isn’t there. Enough of my blather. I don’t want to be confusing you with all this talk. Let’s get on with the work!’

During the day, Brendan went about his work,

and helped with building the wall, which grew higher every day; but in the evenings, he would sneak out of his cell. He would go to the Scriptorium, where Aidan would be waiting to teach him. The other monks would help them, covering for Brendan when he was too sleepy to do the tasks the Abbot set him. They also found the raw materials for the inks and helped with making it. All of them wanted to see the Book completed.

Spring passed into summer and Brendan sometimes slipped out of the monastery with Pangur and met Aisling in the forest. In the woods, he learned as much as he did in the Scriptorium. Aisling taught Brendan all about the different trees of the forest, their natures, their strengths and their weaknesses and their special powers. She introduced him to the animals and birds, which would come to her without any fear. Most of all, she taught him how to see the beauty that was all around him.

The one dark cloud during that summer was that more and more refugees from the Northmen came to Kells, ragged and terrified, telling fearful

tales of the cruelty and violence of the invaders. Each refugee had a story, and each story was sadder than the last. Parents came who had lost their children; children came who had lost their parents. Hundreds of innocent people had been killed or dragged away as slaves.

And at night, after he had seen another group of starving villagers seek refuge in the Abbey and listened to their stories, Brendan would sometimes wake up and find himself shaking with fear. He would have had the dream again, the dream of fire and smoke, of huge shadowy figures leaning over him, waving swords and axes. Of cruel laughter, of crackling flames and screams. Of trying to get away, but not being able to move. That nightmare had come to him from the time he was very small, and he sometimes wondered if it was partly a memory of what had happened to him when his people were attacked, when he was a tiny baby.

One night Aidan and Pangur came up to where Brendan was working and Aidan said to Pangur, ‘Not bad. I’d say he could do it, right enough.’

Pangur miaowed in agreement.

Brendan looked up from where he was carefully sketching an angel’s face. He had drawn the figure balanced on a green stem, sitting there in a way that reminded him of Aisling.

‘Do what?’ he asked, his mind still on his work.

Aidan went to the window and stood with his back to Brendan.

‘I must confess, my boy, I haven’t been completely honest with you. I cannot do the Chi Ro page. My eyes have become too old and my hands unsteady.’

He turned to Brendan. His face was very serious.

‘You should be the one to do the Chi Ro page!’

‘M

e?’ Brendan could not believe his ears. ‘I couldn’t do the Chi Ro page! I’m only a boy! You are the master craftsman. You know what to do. If I tried to do it, I’d only ruin it …’

‘You know, I don’t think you would,’ said Aidan. ‘I have watched you. It’s not just that your eyes are as sharp and your hand is as steady as any I’ve ever seen. You have the gift of sight, my lad, of inner sight, of the eye of the imagination. Your only problem is that you are a bit afraid of it yourself. If you are ever to light up the Chi Ro page, you will have to face up to your fears. There is something stopping you from doing that, but if you do, you will be able to make something that will indeed be the work of angels.’

He paused.

‘Of course you will need something to help you. You will need another eye. Colmcille’s Eye. Colmcille instructed that it should never be used unless the work was worthy of it. It has not been used since Iona. But I am sure that he would want it to go to you.’

‘What?’ said Brendan, ‘The eye? Colmcille’s eye? So it is true he had a third eye? I thought it was just a story, like the one about him having a third hand with twelve fingers!’

‘I can assure you Colmcille had only two hands and the normal number of fingers. And the Eye isn’t a real eye. At least it isn’t a human eye. It is an eye of a very special kind,’ said Aidan, starting to fumble in his satchel. ‘It’s called a crystal. It is the most beautiful and wonderful thing, wherever it’s got to.’ He paused and scrabbled a bit more in the satchel, looking more and more worried as he did so.

‘But the power of the crystal is not just in its beauty. When you look through it, you can see details that even the sharpest-eyed person in the world could not see without it. It is amazing. You can see even down to the pattern on a bee’s wing. That is how Colmcille managed to make such

intricate designs. He kept the Eye hidden. Only a few monks, the ones closest to him, knew about it at all. That was partly to keep it safe, and partly because there are those who might have been afraid of it. They might have argued that it was not the Lord’s will to see too closely. But Colmcille always said that there was nothing the Lord created that could not be used for the good or evil, and it was the choice of man to decide what way to use it. So the good or evil was in the man or woman using the thing, not the thing itself. And the Eye of Colmcille was always used to create beautiful things. When Colmcille lay dying, the Eye dropped from his hand. And since then it has been kept safe in the monastery. When Iona was attacked those were the two treasures entrusted to me by the other monks … the Book and the Eye. But …’

Suddenly, Aidan put his hands to his head in despair.

‘I have lost it, and we cannot make the Book without it! It’s lost! It’s all lost!’

Brendan had never seen Aidan like this and it scared him.

‘Where did you last have it?’ he asked.

Aidan shook his head. He looked desperately unhappy.

‘I have no idea,’ he said. ‘I can’t think what might have happened. I so was sure it was safe in the satchel. That’s why I didn’t even bother to look for it before now. But now that I think of it, it must have been when I fled from Iona. There was that time when I was getting onto the boat, with the Northmen right behind me. I have a vague memory of dropping the satchel and something falling then; it must have been the Eye. It could be anywhere now, anywhere between here and Scotland. Crushed by the Northmen or lost at the bottom of the sea … I have failed, Brendan. Failed in the task my brothers gave me.’

‘Where did the Eye come from?’ asked Brendan. ‘Maybe we can get another one?’

Aidan shook his head.

‘No, I’m afraid that is impossible. The story is that the Eye was captured by Colmcille himself. He fought a great battle with a deadly serpent, one of the Old Ones, in order to win it. He nearly died in the battle, but in the end, he was victorious and

sent the wicked snake howling and yowling deep into its lair under the waters of Lough Ness. Didn’t I tell you our founder was a great warrior as well as a monk? While they fought, he pulled one of the monster’s eyes from its head. He brought it to Iona.’

Aidan sat down heavily at the Scriptorium table and buried his head in his hands.

Pangur came up to him and rubbed her body against his arms, trying to comfort him. Aidan continued:

‘Some say that before the crystal became known as the Eye of Colmcille, it had an ancient name. Named for the creature that Colmcille won it from. It was called the Eye of Crom Cruach.’

Brendan gasped, remembering Crom Cruach’s cave and the way he had been pulled towards its terrible darkness.

Aidan sat for a moment with his head in his hands. Then he looked up and rubbed his eyes wearily. He began to draw the crystal on a piece of parchment.

‘I can’t tell you which parts of the story are true. But the Eye looked like this.’

He showed the picture to Brendan. It was a strange, many faceted pattern which somehow terrified Brendan. And yet it reminded him of the designs that had been carved on the entrance to the cave of the Dark One. He placed his hand on it to hide it; but when he lifted his hand, the Eye stared back at him, imprinted on his palm. He shivered. Aidan was looking into the fire, his shoulders bent in sorrow. His voice was shaking when he spoke.

‘I have failed you too, Brendan, for you could have used the Eye to create something that would be treasured forever. I am just a useless old man …’

‘You are not,’ said Brendan. He tried to think of something else he could say to make Aidan feel better. But there was nothing to say.

That night, as darkness lay over the monastery, Brendan slipped from his bed and pulled on his cloak. Pangur sat in front of him, meowing in a worried way.

‘I know it will be dangerous,’ Brendan said to her. ‘But it was Crom Cruach that Colmcille fought, and that is why Crom Cruach has only one

eye. So his other eye must be a crystal too. And it’s up to me to get it so that the Book can be finished …’

He shivered. Even the thought of going back to that dreadful place in the woods where Crom Cruach had his den was enough to make the hairs on the back of his neck rise up in fear. But I have to get it, he thought; Aidan is too old and there is nobody else to do it.

Even if I do manage to do it, he thought ruefully, and am not killed by the monster, Uncle will probably kill me anyway if he finds out I’ve left the monastery again. But somehow the thought of his uncle’s anger no longer seemed so frightening. He moved carefully to the door of his room. Picking Pangur up and cuddling her, he said, ‘Don’t worry, Pangur, I won’t be alone. But it is too dangerous to bring you along this time. You stay here and mind Aidan while I’m gone.’

Brendan left the tower and began to creep down the steps into the mist, looking back to make sure that Pangur had stayed behind. And so, not looking where he was going, he walked straight into a tall figure. There, blocking his way and

looking angrier than he had ever seen him, was the Abbot. His uncle’s voice was very cold when he said, ‘And where do you think you are going?’

Brendan gulped and said nothing.

‘This has gone on long enough, Brendan. It has to stop. You will have to learn obedience. That is one of the great lessons of this life. Not to question those who know better. You have been getting worse, more foolhardy and disobedient by the day. Especially since you started spending time with Brother Aidan, who no doubt has been putting all sorts of ideas into your head. You have been forbidden to leave the Abbey. Now you are forbidden to enter the Scriptorium. You are forbidden to speak to Aidan, and you are forbidden to paint or draw or illustrate. Your days will be spent doing chores or helping with the wall. Is that clear?’

‘Crystal,’ muttered Brendan, thinking of the Eye. But he couldn’t leave it at that. He had to try to make his uncle understand. He began, ‘But Uncle, just let me explain …’

Cellach interrupted him. ‘There is no need for explanations. I understand perfectly well. I

understand that you are a wilful, disobedient little boy with a head full of dreams and nonsense! I understand that every day the Northmen come closer to us and that the work on the wall cannot be delayed by dreamers and artists! Now it is

you

who must understand. No more excursions, no more Scriptorium, and no more Brother Aidan!’

The Abbot started to walk away from Brendan.

Brendan looked at his back and said quietly, ‘No.’

The Abbot turned around and Brendan looked stubbornly at the ground. It had cost him all of his courage to say that one small word to his uncle.

‘What did you say?’ The Abbot’s voice was as cold as winter.

‘I can’t do that. I can’t give up the Book.’ Brendan could feel tears coming to his eyes but he kept talking. ‘If you would only look at it, at one page of it, you would know why I have to keep making it. It’s so beautiful.’

He paused. For a moment, he thought his uncle was going to relent. He continued eagerly, ‘You must realise how important it is; it’s much more important than the wall. You used to make art

yourself … Brother Aidan said you were an illuminator once …’

But Brendan had gone too far and the Abbot lost patience. ‘That’s enough!’ he said sharply. He grabbed Brendan by the arm and pulled him down the stairs to the little cell in the bottom of the tower, where he banged the door behind him and locked him in. ‘If I can’t trust you to stay out of harm’s way, you will have to remain here until you see sense.’

He sighed, and said more quietly, ‘I don’t want to do this, believe me. But it’s a hard and dangerous world, Brendan. Making pretty drawings is not going to save you from all the bad things that can happen. I wish you could realise that. I’m going to Brother Aidan now, to get that accursed book from him and lock it away somewhere. Somewhere where it won’t take everyone’s mind off the work they are supposed to be doing. Every monk in the place is distracted and Aidan is the cause of it all. That man has caused nothing but trouble since he came here … And as for you, you can stay there until you learn a bit of respect and obedience. Until then, I wash

my hands of you.’

He began to make his way upstairs. Brendan was left listening to the angry swish of his cloak on the stone as he walked quickly up the steps.