The Second World War (90 page)

This lengthy foray may not have been successful, but it provided a boost to morale for Slim’s Fourteenth Army and for the public at home, due to highly optimistic reporting. Important lessons were learned, above all the need to clear proper dropping zones and even landing strips in the jungle. And once the Allies were in a position to provide sufficient transport and fighter support, such operations were more likely to bring rewards. Yet this first long-range penetration had a more important effect. It provoked the Japanese into preparing a major offensive for the spring of 1944, which would lead to the decisive battles of the Burma campaign.

APRIL–AUGUST 1943

S

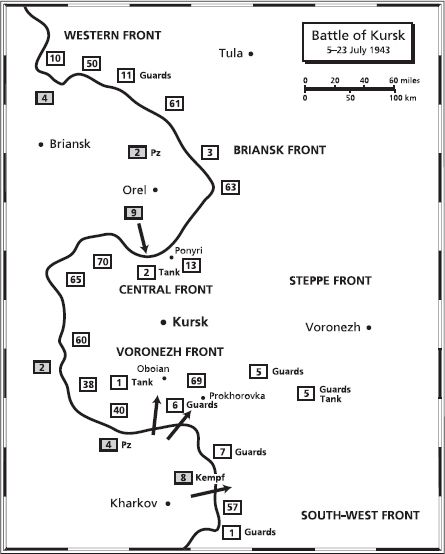

eldom has a major offensive been as obvious to the enemy as the Germans’ Operation Citadel to cut off the Soviet salient round Kursk. Stalin’s commanders estimated that the Germans could afford only one major attack, and the Kursk bulge was clearly the most vulnerable sector of their line. Zhukov and Vasilevsky managed to persuade their impatient leader that the best strategy was to prepare for this double thrust, defeat it in defence and then go over to the offensive themselves.

The German build-up in April 1943 was carefully observed by air reconnaissance flights, by partisan detachments behind the lines and by Soviet agents. The British passed on a warning based on an Ultra intercept, but heavily disguised to conceal its source. The Soviet spy John Cairncross provided far more detail. Yet uncertainty was caused in Moscow by repeated German delays. Generalfeldmarschall von Manstein wanted the operation launched in early May after the end of the spring rains, but Hitler was uncharacteristically nervous and delay followed delay.

The Führer was staking virtually all their reserves on this one giant gamble to shorten the front and regain the initiative, to reassure wavering allies after the defeat at Stalingrad and the retreat in the Caucasus. ‘

Victory at Kursk

will be a beacon for the whole world,’ Hitler proclaimed in his order of 15 April. Yet during the Allied victory in Tunisia he began to look anxiously at the map of Sicily and Italy. ‘

When I think of this attack

,’ he told Guderian, ‘my stomach turns over.’

Many senior officers had their own doubts about the offensive. To compensate for its numerical inferiority, the German army had always relied on its greatest ability: to wage a

Bewegungskrieg

or war of movement. But the Kursk Offensive looked as if it might turn into a battle of attrition. As in a game of chess when you are already several pieces down, the risks multiply the moment you lose the initiative and try to attack again. The German army’s queen, its armoured forces, was about to be thrown into a battle which would be more dangerous for the Wehrmacht than for the Red Army, which now enjoyed such superiority in numbers and weaponry.

OKW staff officers began to voice doubts about the thinking behind Operation Citadel, but this, perversely, now made Hitler more determined to continue. Planning for the operation took on a momentum of its own.

Hitler felt unable to back down. He dismissed the air reconnaissance reports on the strength of Soviet defences, claiming they were exaggerated. Yet, despite Manstein’s desire for an early attack, Citadel was still postponed numerous times to allow more tanks, such as the new Mark V Panther, to be rushed to the front after the delays caused by RAF bombing. The great offensive did not in the end begin until 5 July.

This crucial breathing space granted to the Red Army was not wasted. Its formations and some 300,000 mobilized civilians were put to work on the construction of eight lines of defence, with deep tank ditches, underground bunkers, minefields, wire entanglements and over 9,000 kilometres of trenches. Every soldier, in true Soviet style, was set a target of digging five metres of trench every night since it was too dangerous by day. In places the defences went back nearly 300 kilometres. All civilians not involved in digging and who lived within twenty-five kilometres of the front were evacuated. Reconnaissance patrols were sent out at night to seize Germans for interrogation. These snatch parties consisted of men picked for their size and strength to overpower a sentry or ration carrier. ‘

Each reconnaissance group

was given a couple of sappers who would lead them through our mines and make a corridor for them in the German minefield.’

Most importantly, a large strategic reserve known as the Steppe Front and commanded by Colonel General I. S. Konev was assembled to the rear of the bulge. It included the 5th Guards Tank Army, five rifle armies, another three tank and mechanized corps and three cavalry corps. Altogether the Steppe Front mustered nearly 575,000 men. They were supported by the 5th Air Army. The movement and the positions of these formations were concealed as far as possible, in order to deceive the Germans about the Red Army’s preparations for a powerful counter-stroke. Further deception measures included the massing of other forces in the south and the construction of dummy airfields to imply preparations for an offensive there.

Normally an attacking force requires a superiority of up to three to one over the defenders, but in July 1943 this was reversed. The Soviet army groups involved–Rokossovsky’s Central Front, Vatutin’s Voronezh Front, Malinovsky’s South-Western Front and Konev’s Steppe Front–totalled over 1,900,000 men. German strength for Operation Citadel did not exceed 780,000. It represented a huge gamble.

The Germans placed their faith in panzer wedges, using companies of Tiger tanks as spearheads to batter a hole in the Soviet defence lines. The II SS Panzer Corps, which had retaken Kharkov and then Belgorod in March, was refitting. Brought up to strength mainly by Luftwaffe ground personnel, the 1st SS Panzer Division

Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler

put the new arrivals through an intensive training programme. SS

Untersturmführer Michael

Wittmann

, who was to become the greatest panzer ace of the war, took command of his first Tiger platoon at this point. But despite the unquestioned superiority of the Tiger, the Waffen-SS panzergrenadier divisions were acutely conscious of their inferiority in equipment. The SS

Das Reich

even had to equip one of its companies with captured T-34s.

Ultra intelligence, passed by Cairncross to the Soviet Foreign Intelligence Department through his handler in London, had also identified the

Luftwaffe airfields

in the region. Some 2,000 aircraft were being concentrated there, the bulk of what was left on the eastern front after so

many squadrons had been sent back to defend Germany from the Allied air forces. Red Army aviation regiments were thus able to launch preemptive strikes early in May, apparently destroying more than 500 aircraft on the ground. The Luftwaffe also suffered from a shortage of aviation fuel, which restricted its ability to support the attacking troops.

German supply problems had been growing with the ferocious partisan campaign fought far behind the Wehrmacht’s lines. Certain areas, such as the forests south of Leningrad and large parts of Belorussia, were almost completely controlled by partisan forces, now directed from Moscow. The German anti-partisan sweeps grew in violence. SS Brigadeführer Oskar Dirlewanger and his group recruited from released criminals exterminated and burned whole villages. For the Germans’ Kursk Offensive, Soviet partisan groups were put on standby to attack railways lines to slow supplies.

The continued postponements of the German offensive encouraged impatient commanders such as Colonel General Vatutin to argue that they should not wait. The Red Army should launch its own attack instead. Zhukov and Vasilevsky again had to calm Stalin and persuade him that they must be patient. They would destroy far more Germans for fewer losses in defence than in attack. Stalin was not in the best of moods, having heard from Churchill at the beginning of June that an Allied invasion of northern France was now pushed back until the following May.

Stalin was also bitter about the international row which had broken out over the mass murder of Polish prisoners of war, in the forest of Katy and elsewhere. In late April the Germans, on hearing of the mass grave, summoned an international commission of doctors from allied and occupied nations to examine the evidence. The London-based Polish government-in-exile demanded a full inquiry by the International Red Cross. Stalin angrily insisted that the victims had been killed by the Germans, and that anyone who doubted this was ‘aiding and abetting Hitler’. On 26 April, Moscow severed diplomatic relations with the London Polish government. The death of General

and elsewhere. In late April the Germans, on hearing of the mass grave, summoned an international commission of doctors from allied and occupied nations to examine the evidence. The London-based Polish government-in-exile demanded a full inquiry by the International Red Cross. Stalin angrily insisted that the victims had been killed by the Germans, and that anyone who doubted this was ‘aiding and abetting Hitler’. On 26 April, Moscow severed diplomatic relations with the London Polish government. The death of General

Sikorski

on 4 July had been the result of a tragic accident, when the cargo aboard the Liberator he was on shifted to the back of the plane on take-off. After the news from Katy , and Sikorski’s demands for a full inquiry, Poles naturally suspected sabotage.

, and Sikorski’s demands for a full inquiry, Poles naturally suspected sabotage.

On 15 May, Stalin, apparently in an attempt to reassure Britain and especially the United States which provided such vital assistance with Lend– Lease, announced that he had abolished the Comintern. But this gesture was also intended to divert attention from the row over the Katy killings. In fact the Comintern, directed by Georgii Dimitrov, Dmitri Manuilsky and Palmiro Togliatti, simply continued to operate from the International Section of the Central Committee.

killings. In fact the Comintern, directed by Georgii Dimitrov, Dmitri Manuilsky and Palmiro Togliatti, simply continued to operate from the International Section of the Central Committee.

In the afternoon of 4 July, a hot and humid day with occasional cloudbursts, German panzergrenadier units from the

Grossdeutschland

and the 11th Panzer Division finally began their probing attacks against forward Soviet positions on the southern Belgorod sector. That night, German pioneer companies from Model’s Ninth Army began to cut wire and remove mines on the northern sector. A German soldier was captured and interrogated. Information was passed to General Rokossovsky, commander-in-chief of the Central Front, that H-Hour was to be at 03.00 hours. He rapidly gave the order for a massive harassing bombardment with guns, heavy mortars and Katyusha rocket-launchers against Model’s Ninth Army. Zhukov rang Stalin to tell him that the battle had finally started.

Vatutin’s forces on the southern side of the salient, who had also interrogated a German prisoner, began their pre-emptive fire against Hoth’s Fourth Panzer Army soon afterwards. Both the Ninth Army and the Fourth Panzer Army felt obliged to delay their attacks by up to two hours. They even wondered whether the Soviets were about to launch their own offensive. Although the Germans suffered comparatively few casualties from this shelling, they now knew for certain that the Red Army was ready and waiting for them on their axes of advance. Combined with a heavy thunderstorm, it was hardly an encouraging start.