The Savage Altar

PENGUIN BOOKS

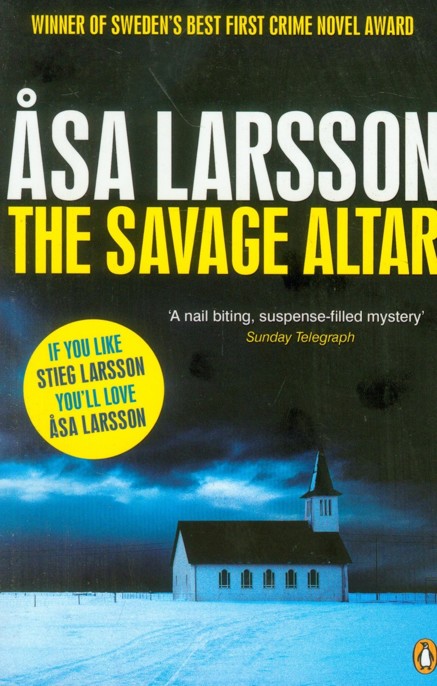

THE SAVAGE ALTAR

Åsa Larsson was born in Kiruna, Sweden, in 1966.

The Savage Altar

won Sweden’s Best First Crime Novel Award. Åsa Larsson’s second novel,

The Blood Spilt,

will be published by Viking in 2008.

THE SAVAGE

ALTAR

Åsa

Larsson

Translated by Marlaine Delargy

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in Sweden by Albert Bonniers as

Solstorm

2003

First published in the United States of America by Bantam Dell as

Sun Storm 2006

First published in Great Britain by Viking as

The Savage Altar

2007

Published in Penguin Books 2008

1

Copyright © Åsa Larsson, 2003

Translation copyright © by The Bantam Dell Publishing Group,

a division of Random House, Inc. 2003

All rights reserved

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN: 978-0-14-191716-0

It grows like a tree of rage

behind my brow

with flashing red leaves, blue leaves, white!

A tree

still quivering in the wind

And I will crush

your house, and nothing

will be unfamiliar to me,

not even

what is human

Like a tree from the inside

forces its way out

and crushes

the skull

And glows

like a lantern deep in the forest

deep in the darkness

Göran

Sonnevi

And evening came and morning came, the first day

W

hen Viktor Strandgård dies it is not, in fact, for the first time. He lies on his back in the church called The Source of All Our Strength and looks up through the enormous windows in its roof. It’s as if there is nothing between him and the dark winter sky up above.

You can’t get any closer than this, he thinks. When you come to the church on the mountain at the end of the world, the sky will be so close that you can reach out and touch it.

The Aurora Borealis twists and turns like a dragon in the night sky. Stars and planets are compelled to give way to her, this great miracle of shimmering light, as she makes her unhurried way across the vault of heaven.

Viktor Strandgård follows her progress with his eyes.

I wonder if she sings? he thinks. Like a lonely whale beneath the sea?

And as if his thoughts have touched her, she stops for a second. Breaks her endless journey. Contemplates Viktor Strandgård with her cold winter eyes. Because he is as beautiful as an icon lying there, to tell the truth, with the dark blood like a halo round his long, fair, St. Lucia hair. He can’t feel his legs anymore. He is getting drowsy. There is no pain.

Curiously enough it is his previous death he is thinking of as he lies there looking into the eye of the dragon. That time in the late winter when he came cycling down the long bank toward the crossroads at Adolf Hedinsvägen and Hjalmar Lundbohmsvägen. Happy and redeemed, his guitar on his back. He remembers how the wheels of his bicycle skidded helplessly on the ice as he tried desperately to brake. How he saw the woman in the red Fiat Uno coming from the right. How they stared at each other, the realization in the other’s eyes; now it’s happening, the icy slide toward death.

With that picture in his mind’s eye Viktor Strandgård dies for the second time in his life. Footsteps approach, but he doesn’t hear them. His eyes do not have to see the gleam of the knife once again. His body lies like an empty shell on the floor of the church; it is stabbed over and over again. And the dragon resumes her journey across the heavens, unmoved.

Monday, February 17

R

ebecka Martinsson was woken by her own sharp intake of breath as fear stabbed through her body. She opened her eyes to darkness. Just between the dream and the waking, she had the strong feeling that there was someone in the flat. She lay still and listened, but all she could hear was the sound of her own heart thumping in her chest like a frightened hare. Her fingers fumbled for the alarm clock on the bedside table and found the little button to light up the face. Quarter to four. She had gone to bed four hours ago and this was the second time she had woken up.

It’s the job, she thought. I work too hard. That’s why my thoughts go round and round at night, like a hamster on a squeaking wheel.

Her head and the back of her neck were aching. She must have been grinding her teeth in her sleep. Might as well get up. She wound the duvet around her and went into the kitchen. Her feet knew the way without her needing to switch on. the light. She put on the coffee machine and the radio. Bellman’s music played over and over as the water ran through the filter and Rebecka showered.

Her long hair could dry in its own time. She drank her coffee while she was getting dressed. Over the weekend she had ironed her clothes for the week and hung them up in the wardrobe. Now it was Monday. On Monday’s hanger was an ivory blouse and a navy blue Marella suit. She sniffed at the tights she’d been wearing the previous day; they’d do. They’d gone a bit wrinkly around the ankles, but if she stretched them and tucked them under her feet it wouldn’t show. She’d just have to make sure she didn’t kick her shoes off during the day. It didn’t bother her; it was only worth spending time worrying about your underwear and your tights if you thought somebody was going to be watching you get undressed. Her underwear had seen better days and was turning gray.

An hour later she was sitting at her computer in the office. The words flowed through her mind like a clear mountain stream, down her arms and out through her fingers, flying over the keyboard. Work soothed her mind. It was as if the morning’s unpleasantness had been blown away.

It’s strange, she thought. I moan and complain like all the other young lawyers about how unhappy the job makes me. But I feel a sense of peace when I’m working. Happiness, almost. It’s when I’m not working I feel uneasy.

The light from the street below forced its way with difficulty through the tall barred windows. You could still make out the sound of individual cars among the noise below, but soon the street would become a single dull roar of traffic. Rebecka leaned back in her chair and clicked on “print.” Out in the dark corridor the printer woke up and got on with the first task of the day. Then the door into reception banged. She sighed and looked at the clock. Ten to six. That was the end of her peace and quiet.

She couldn’t hear who had come in. The thick carpets in the corridor deadened the sound of footsteps, but after a while the door of her room opened.

“A

m I disturbing you?” It was Maria Taube. She pushed the door open with her hip, balancing a mug of coffee in each hand. Rebecka’s copy was jammed under her right arm.

Both women were newly qualified lawyers with special responsibility for tax laws, working for Meijer & Ditzinger. The office was at the very top of a beautiful turn-of-the-century building on Birger Jarlsgatan. Semi-antique Persian carpets ran the length of the corridors, and here and there stood imposing sofas and armchairs in attractively worn leather. Everything exuded an air of experience, influence, money and competence. It was an office that filled clients with an appropriate mixture of security and reverence.

“By the time you die you must be so tired you hope there won’t be any sort of afterlife,” said Maria, and put a mug of coffee on Rebecka’s desk. “But of course that won’t apply to you, Maggie Thatcher. What time did you get here this morning? Or haven’t you been home at all?”

They’d both worked in the office on Sunday evening. Maria had gone home first.

"I’ve only just got here," lied Rebecka, and took her copy out of Maria’s hand.

Maria sank down into the armchair provided for visitors, kicked off her ridiculously expensive leather shoes and drew her legs up under her body.

“Terrible weather,” she said.

Rebecka looked out the window with surprise. Icy rain was hammering against the glass. She hadn’t noticed earlier. She couldn’t remember if it had been raining when she came into work. In fact, she couldn’t actually remember whether she’d walked or taken the Underground. She gazed in a trance at the rain pouring down the glass as it beat an icy tattoo.

Winter in Stockholm, she thought. It’s hardly surprising that you shut down your brain when you’re outside. It’s different up at home, the blue shining midwinter twilight, the snow crunching under your feet. Or the early spring, when you’ve skied along the river from Grandmother’s house in Kurravaara to the cabin in Jiekajärvi, and you sit down and rest on the first patch of clear ground where the snow has melted under a pine tree. The tree bark glows like red copper in the sun. The snow sighs with exhaustion, collapsing in the warmth. Coffee, an orange, sandwiches in your rucksack.

The sound of Maria’s voice drew her back. Her thoughts scrabbled and tried to escape, but she pulled herself together and met her colleague’s raised eyebrows.

“Hello! I asked if you were going to listen to the news.”

“Yes, of course.”

Rebecka leaned back in her chair and stretched out her arm to the radio on the windowsill.

Lord, she’s thin, thought Maria, looking at her colleague’s rib cage as it protruded from under her jacket. You could play a tune on those ribs.

Rebecka turned the radio up and both women sat with their coffee cups cradled between their hands, heads bowed as if in prayer.

Maria blinked. It felt as if something were scratching her tired eyes. Today she had to finish the appeal for the county court in the Stenman case. Måns would kill her if she asked him for more time. She felt a burning pain in her midriff. No more coffee before lunch. You sat here like a princess in a tower, day and night, evenings and weekends, in this oh-so-charming office with all its bloody traditions that could go to hell, and all the pissed-up partners looking straight through your blouse while outside, life just carried on without you. You didn’t know whether you wanted to cry or start a revolution but all you could actually manage was to drag yourself home to the TV and pass out in front of its soothing, flickering screen.

It’s six o’clock and here are the morning headlines. A well-known religious leader around the age of thirty was found murdered early this morning in the church of The Source of All Our Strength in Kiruna. The police

in Kiruna are not prepared to make a statement about the murder at this stage, but during the morning they have revealed that no one has been detained so far, and the murder weapon has not yet been found…. A new study shows that more and more communities are ignoring their obligations, according to Social Services….

Rebecka swung her chair round so quickly that she banged her hand on the windowsill. She turned the radio off with a crash and at the same time managed to spill coffee on her knee.

“Viktor,” she exclaimed. “It has to be him.”

Maria looked at her with surprise.

“Viktor Strandgård? The Paradise Boy? Did you know him?”

Rebecka avoided Maria’s gaze. Ended up staring at the coffee stain on her skirt, her expression closed and blank. Thin lips, pressed together.

“Of course I knew of him. But I haven’t been home to Kiruna for years. I don’t know anybody up there anymore.”

Maria got up from the armchair, went over to Rebecka and pried the coffee cup from her colleague’s stiff hands.

“If you say you didn’t know him, that’s fine by me, but you’re going to faint in about thirty seconds. You’re as white as a sheet. Bend over and put your head between your knees.”

Like a child Rebecka did as she was told. Maria went to the bathroom and fetched paper towels to try to save Rebecka’s suit from the coffee stain. When she came back Rebecka was leaning back in her chair.

“Are you okay?” asked Maria.

“Yes,” answered Rebecka absently, and looked on helplessly as Maria started to dab at her skirt with a damp towel. “I did know him,” she said.

“Well, I didn’t exactly need a lie detector,” said Maria without looking up. “Are you upset?”

“Upset? I don’t know. Frightened, maybe.”

Maria stopped her frantic dabbing.

“Frightened of what?”

“I don’t know. That somebody will—”

The telephone burst in with its shrill signal before Rebecka could finish. She jumped and stared at it, but didn’t pick it up. After the third ring Maria answered. She put her hand over the receiver so that the person on the other end couldn’t hear her, and whispered:

“It’s for you and it must be from Kiruna, because there’s a Moomintroll on the other end.”