The Real History of the End of the World (10 page)

Read The Real History of the End of the World Online

Authors: Sharan Newman

BOOK: The Real History of the End of the World

7.33Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

This providential line caused his conversion to be total. He was baptized along with his son. They set off to return to Africa, with Augustine's mother, Monica, and with friends and family members. While waiting for a ship at Ostia, Monica fell ill and died. This loss crushed Augustine, and he spent another year in Rome working through his grief. When he returned to Africa, his son, Adeodatus, suddenly died at the age of about fifteen.

Afterward, perhaps to work through his grief Augustine founded a monastic retreat where he stayed until he was ordained a priest in 389. He became bishop of Hippo in 396 and remained so until his death in 430, while a Vandal army was besieging the city.

Although in his last days Augustine may have felt that the world had to be ending, his philosophy argues that, even though the end will come, it is not possible to predict. This is most thoroughly expressed in book twenty of his monumental

City of God.

City of God.

Augustine uses his rhetorical training to present each of the main points of his argument. He begins with the statements given by Jesus in the Gospels. Starting with Matthew and the parable of the wheat and the tares, Augustine deduces that Christ has promised a day of judgment at which the dead shall rise (Matthew 13:37-43). The twelve Apostles are also told that they shall sit in judgment of the twelve tribes of Israel (Matthew 19:28). Augustine also cites several places in which the faithful are assured that the wicked shall be punished.

dt

dt

Then Augustine departs from the still-current belief that the end will come soon by quoting from John (5:25): “The hour is coming and is now.” Augustine takes this to mean that the time has come for believers, who were once dead to Christ, to be reborn in the Church. “He, therefore, who would not be damned in the second resurrection, let him rise in the first.”

du

du

Next Augustine tackles the millenarians, who have been driving him crazy. He thinks that the idea of a thousand years of Sabbath is not bad and admits that he once believed this himself. But many people seem to have decided that the Sabbath didn't mean going to church, praying, and appreciating creation. They thought it meant a thousand years of holiday, to party with everything one could think of to eat and drink.

dv

dv

Patiently, Augustine explains the allegorical interpretation of the Apocalypse. We are in the millennium, he states. It began with the incarnation, at which time Satan was thrown into the abyssâthat is, into the hearts of the wicked and unbelievers. He is chained and prevented from seducing the nations of the faithful. At the end of a thousand years, Satan shall be freed and gather an army to attack the Church. But Augustine is firm that the true believers shall never be fooled into following him. Some weak Christians may be swayed, but those predestined for heaven won't waver.

dw

dw

Therefore, Augustine is a postmillennialist. He believes that we are living in the first thousand years and at the end of it will come the Second Advent. Augustine interprets Gog and Magog of Revelation to mean the nations in which the Devil was confined. He states that it's pointless to try to identify them with real places. He also admits that the Apocalypse seems to skip from literal to figurative terms. “No doubt, though this book is called the Apocalypse, there are in it many obscure passages to exercise the mind of the reader, and there are few passages so plain as to assist us in the interpretation of the others, even though we take pains; and this difficulty is increased by the repetition of the same things, in forms so different, that the things referred to seem to be different, although in fact they are only differently stated.”

dx

dx

I find it comforting that someone as brilliant and devout as Augustine couldn't make sense of the book, either.

Augustine agrees with the by then established belief that the dead shall rise bodily at the end, that the saints and sinners shall be judged, and that there shall be a blissful eternity for the elect.

By the time he finished the

City of God

, about 426, Augustine was nearly seventy. He had witnessed cataclysmic changes in the Roman Empire. However, instead of looking for omens of the end in earthquakes and wars, he insisted that the real battles were spiritual.

City of God

, about 426, Augustine was nearly seventy. He had witnessed cataclysmic changes in the Roman Empire. However, instead of looking for omens of the end in earthquakes and wars, he insisted that the real battles were spiritual.

He was also irritated by people who constantly tried to figure out when the Second Advent would be. “A most unreasonable question,” he tells them. “For if it were good for us to know the answer, the Master, God himself, would have told His disciples when they asked him.”

dy

dy

Augustine was not the first or the last to say this, but he was one of the most eloquent. His books,

Confessions, The City of God,

and

On Christian Doctrine

were tremendously influential in setting the policy of the Roman Church for the next thousand years. While people still tried to figure out the end time, since humans naturally have a need to know and control events, there were few real millennial movements until the early fourteenth century.

Confessions, The City of God,

and

On Christian Doctrine

were tremendously influential in setting the policy of the Roman Church for the next thousand years. While people still tried to figure out the end time, since humans naturally have a need to know and control events, there were few real millennial movements until the early fourteenth century.

Augustine also considered astrology to be nonsense and did not believe that Jews should be persecuted because their ancestors had a role in the death of Christ. These ideas were too much for most of his contemporaries and later readers to accept. However, his reading of the Apocalypse helped hold down doomsday panic throughout the Middle Ages.

Then came the Reformation, and all hell broke loose, so to speak.

PART THREE:

The Middle Ages

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

The Calm between the Panics

Just before the third year after the millennium, throughout the

whole world . . . men began to reconstruct churches. . . . It was

as if the whole world were shaking itself free, shrugging off the

burden of the past and cladding itself everywhere in a white

mantle of churches.

whole world . . . men began to reconstruct churches. . . . It was

as if the whole world were shaking itself free, shrugging off the

burden of the past and cladding itself everywhere in a white

mantle of churches.

âRadolphus Glaber,

Historia Libri Quinque,

book III, part 13

Historia Libri Quinque,

book III, part 13

Â

Â

Â

Â

T

he image of the European Middle Ages in popular fiction and film is generally one of dirt, superstition, and religious fanaticism. Thus people who have only that impression of the time from, say, 900 to 1450 would expect it to be full of millennial and apocalyptic movements. That isn't the case, at least not for medieval Europe.

he image of the European Middle Ages in popular fiction and film is generally one of dirt, superstition, and religious fanaticism. Thus people who have only that impression of the time from, say, 900 to 1450 would expect it to be full of millennial and apocalyptic movements. That isn't the case, at least not for medieval Europe.

By the Middle Ages, people in Western Christendom had become used to the idea of the Second Coming, Armageddon, and the Last Judgment. Scenes of them were in art everywhere one looked. But, for most people, the end of the world was rather like background radiation or Muzak. They knew it was there but didn't pay much attention to it. The monk Robert of Flavigny found this distressing. “Such is the state of the Church today that you see people of perfect faith, with whom, if you have a conversation about the final persecution and the coming of Antichrist, it seems as if they hardly believe it will come, or, if they believe it, in a dreamy way will attempt to demonstrate that it will happen after many centuries.”

dz

dz

Of course, an earthquake or a particularly nasty invasion might jolt people into wondering if this were the Big One, rather like Californians who know a monster quake is coming but assume it won't be right now. Still, whenever there's a tremor, it crosses their minds that they might have been wrong.

The years between about 1000 and 1350 were a time of expansion. The climate was mild and harvests abundant. This allowed peasants, who usually paid a fixed amount in taxes and tithes, to have enough left over to sell at markets. Many settled new villages under favorable terms from local lords. Now I don't think it was just good weather that kept medieval society from believing that the Apocalypse was imminent. But good crops, spare cash, and new frontiers do tend to make people think things aren't so bad. By the late 900s even the Vikings were settling down and learning French.

There were a few interesting apocalyptic trends, particularly toward the end of the period, when the earth entered the little Ice Age.

ea

The increasing cold led to crop failure, famine, and disease. These set the stage for both political and religious upheaval.

ea

The increasing cold led to crop failure, famine, and disease. These set the stage for both political and religious upheaval.

There is another reason that there were few millennial movements in Europe during this time. It wasn't a politically sound proposition. The Roman Church had come to terms with the Book of Revelation. The end was coming, of course, but there were a lot of things that needed to be done first. One of the standard beliefs was that Christ would not return until all the Jews converted to Christianity. Now, I know that forced baptism occurred, especially in the Rhineland and in Spain. However, it was never sanctioned by Rome. The sensible reason they gave was that conversion has to come from the heart. The reason that carried more weight with the public was that, if all the Jews became Christian, then doom was at hand. Unlike the First Christians, most medieval Christians weren't all that eager for the end.

That didn't prevent them from talking about it, writing about it and painting pictures of it.

What medieval philosophers, theologians, and visionaries did was set the stage for later developments. It's at this time that the stories of what would happen at the end and of the Antichrist were developed.

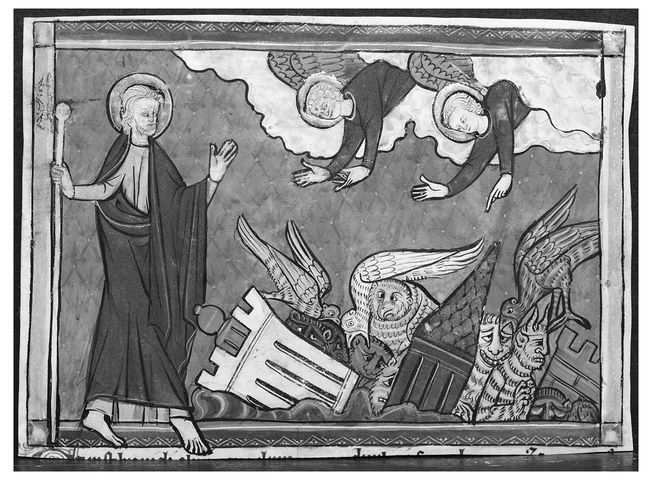

Miniature from a Manuscript of the Apocalypse: The Fall of Babylon

. France, Lorraine, c. 1295. Ink, tempera, and gold on vellum, 12 14.2 cm.

The Cleveland Museum of Art, John L . Severance Fund, 1983.73.1.b

. France, Lorraine, c. 1295. Ink, tempera, and gold on vellum, 12 14.2 cm.

The Cleveland Museum of Art, John L . Severance Fund, 1983.73.1.b

This is reflected in the late-thirteenth-century picture from the Apocalypse of John shown above. The scene is the fall of Babylon, and John is on the left. Unlike similar scenes from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the sense is that Babylon is a stage set from one of the religious plays staged every year by the guilds. The beasts are very much like Maurice Sendak drawings. In this and in most high medieval representations of the Apocalypse, there is no sense of terror or foreboding. It's something to make fun of because the reality is a long way off.

They knew it was a long way off because by the sixth century, when the world didn't end in 500 C.E., as predicted by some theologians, the concept of the ages of the world that the Greeks had perfected had been firmly adapted to Christian time, and while they were probably in the final age (aren't we always?), it was still early on.

Â

Â

IT had been suggested that the crusades were a millennial movement in the sense that returning the Holy Land to Christians was the beginning of the events that would lead to the Second Coming. It seems plausible that there were some crusaders who did think so, although not all by any means.

eb

The crusaders didn't take their millennial belief from the Bible so much as the Tiburtine Sibylline Oracles. The Sybil had been keeping up her prophecies through a number of Christian interpreters (and forgers) with hardly a break since the fall of Rome. In a popular forecast, she tells of a Last World Emperor, a human king who will destroy the Muslims, establish himself in Jerusalem, and usher in a Golden Age that will prepare the world for the end.

ec

Whether the conquerors of Jerusalem thought of themselves in the light of an army out to pave the way for the Last World Emperor is hard to say. In my own work on the Crusades, I don't sense that Godfroye de Bouillon, his brother Baldwin, or any of the other leaders of the armies that took Jerusalem played the millennium card in their struggles for power after the conquest.

eb

The crusaders didn't take their millennial belief from the Bible so much as the Tiburtine Sibylline Oracles. The Sybil had been keeping up her prophecies through a number of Christian interpreters (and forgers) with hardly a break since the fall of Rome. In a popular forecast, she tells of a Last World Emperor, a human king who will destroy the Muslims, establish himself in Jerusalem, and usher in a Golden Age that will prepare the world for the end.

ec

Whether the conquerors of Jerusalem thought of themselves in the light of an army out to pave the way for the Last World Emperor is hard to say. In my own work on the Crusades, I don't sense that Godfroye de Bouillon, his brother Baldwin, or any of the other leaders of the armies that took Jerusalem played the millennium card in their struggles for power after the conquest.

But that doesn't mean that the rank and file among the crusaders didn't see their actions as helping the millennium along. One of their earliest efforts to end the world was to massacre the Jews in the Rhineland. Their rationale for this has always been that these were the infidels in their midst; therefore, it was only right to rid Europe of them. The vague understanding that all the Jews were supposed to be converted before Christ returned became secondary to stamping them out, although there were also a number of forced conversions.

Other books

The Ghosts of Kerfol by Deborah Noyes

Simply Pleasure by Kate Pearce

Twitter for Dummies by Laura Fitton, Michael Gruen, Leslie Poston

FROSTBITE by David Warren

Loud: The Complete Series (A Bad Boy Alpha Male Romance) by Claire Adams

Devil Sent the Rain by D. J. Butler

The Prince Charles Letters by David Stubbs

Hard Bite by Anonymous-9

Ghostwritten by David Mitchell

The Lieutenant’s Lover by Harry Bingham