The Penguin Book of Card Games: Everything You Need to Know to Play Over 250 Games (148 page)

Read The Penguin Book of Card Games: Everything You Need to Know to Play Over 250 Games Online

Authors: David Parlett

scored simultaneously, as at Hol ywood Gin (q.v.). Game is 100

points.

Mau-Mau

(3-5p, 32c) This is apparently the earliest member of the family to

require beginners to learn the rule by play rather than by

instruction. Deal five each from a 32-card pack, turn the next as a

starter, and stack the rest face down. Play as Crazy Eights, except

that Jacks are wild instead of Eights. You must cal ‘Mau’ upon

playing your last card, or ‘Mau-Mau’ if it is a Jack, in which case

you win double. The penalty for not doing so is to draw a card

from stock and keep playing. Cards left in others’ hands score

against them thus: each Ace 11, Ten 10, King 4, Queen 3, Jack 2 (or

20), others zero (or face value). End when someone reaches 100

penalties.

Neuner

(‘Nines’) (3-5p, 32c) As Mau-Mau, except that a Joker is added, and

it and al Nines are wild.

Go Boom

(3-10p, 52c) This game only dif ers from Rol ing Stone (see Durak

family) in that players who cannot fol ow draw from stock instead

of from the played-out cards.

Deal seven cards each (or, by some accounts, ten) from a ful

pack – or, if more than six play, a doubled pack of 104 cards – and

stack the rest face down. Eldest leads any card face up. Each in turn

thereafter must play a card of the same suit or rank if possible. A

player unable to do so must draw cards from stock until able, or,

when no cards remain in stock, must simply pass. When everyone

has played or passed, the person who played the highest card of the

suit led turns the played cards down and leads to the next ‘trick’.

Play ceases the moment anyone plays the last card from their

hand. That player scores the total values of al cards remaining in

other players’ hands, with Ace to Ten at face value and courts 10

each.

Switch(Two-Four-Jack, Black Jack)

2-7 players, 52 cards

This game became popular in the 1960s, and gave rise to a

successful proprietary version cal ed Uno. Play as Crazy Eights or

Rockaway, except that a player unable to fol ow draws only one

card from stock, and with the fol owing special rules.

Aces are wild.

Twos Playing a Two forces the next in turn either to play a Two, or,

if unable, to draw two cards from stock and miss a turn. If he

draws, the next in turn may play in the usual way; but if he does

play a Two, the next after him must either do likewise or draw four

cards and miss a turn. Each successive playing of a Two increases by

two the number of cards that must be drawn by the next player if

he cannot play a Two himself, up to a maximum of eight.

Fours have the same powers, except that the number of cards to be

drawn is four, eight, twelve or sixteen, depending on how many are

played in succession.

Jacks Playing a Jack reverses (‘switches’) the direction of play and

forces the preceding player to miss a turn, unless he, too, can play a

Jack, thus turning the tables.

Twos, Fours and Jacks operate independently of one another. You

cannot escape the demands of a Two by playing a Four instead, or

of a Jack by playing a Two, and so on.

The game ends when a player wins by playing his last card. A

player with two cards in hand must announce ‘One left’ or ‘Last

card’ upon playing one of them.

The penalty for any infraction of the rules (including playing too

slowly) is to draw two cards from stock.

The winner scores the face value of al cards left in other players’

hands, with special values of 20 per Ace, 15 per Two, Four or Jack,

and 10 per King and Queen.

Bartok (Warthog)

A form of Crazy Eights in which the winner of each round makes

up a new rule of play. For example, Oedipus Jack means any Jack

can be played on any Queen, regardless of suit, but not on any King,

even of the same suit. (From Lisa Dusseault’s website.)

Eleusis

4-8 players, 104-208 cards

Eleusis formal y resembles a game of the Crazy Eights type, but

turns the whole idea on its head by concealing the rule of matching

that determines whether a given card can legal y be played to the

discard pile. The current dealer invents the rule and the players

have to deduce what it is before they can successful y play their

cards of . This involves a process of inductive thinking similar to

that which underlies scientific investigation into the laws of Nature:

you observe what happens, hypothesize a cause, test your

hypothesis by predicting the outcome of experiments, modify it

until it appears to work, then accept it as a theory so long as it

continues to produce results. Eleusis was invented by American

games inventor Robert Abbot in his student days, and was first

described in Martin Gardner’s Mathematical Games department of

Scientific American in 1959. A more refined version appeared in

Abbot ’s New Card Games (1963), and this further extension

separately in 1977, to which the inventor has recently added some

scoring refinements incorporated below. Abbot ’s bril iant

innovation probably generated the current craze for requiring

newcomers to games of the Crazy Eights family to pick the rules up

as they go along.

Preliminaries From four to eight players start by shuf ling two 52-

card packs together. At least one other pack should be available,

but must be kept apart until needed (if ever). Cards rank

A23456789TJQK. Unless otherwise stated, an Ace counts as

numeral 1, Jack as 11, Queen 12, and King 13.

Deal Nobody deals twice in the same session, but the dealership

should not rotate regularly but be al ocated at random to someone

who has not yet dealt. The dealer receives no cards and plays a

dif erent role from the others. Deal fourteen to each other player,

then one card face up as a starter, and stack the rest face down.

Players’ object To deduce the rule that wil enable them to play of

Players’ object To deduce the rule that wil enable them to play of

their cards to a mainline sequence extending rightwards from the

starter. A card can be played to the mainline only if it correctly

fol ows a rule of play secretly specified by the dealer. Deductions

are made by formulating and testing hypotheses as to what the rule

might be, on the basis of information gained by noting which cards

are accepted and which rejected by the dealer.

Dealer’s object To devise a rule that is neither too easy nor too hard

to deduce. A typical elementary rule is: ‘If the last card is red, the

next card played must be even; if it is black, the next must be odd.’

The dealer writes this rule down on a piece of paper, and may refer

to it at any time, but does not say what it is (though he may give

clues, such as ‘Colours are significant, but not individual suits’).

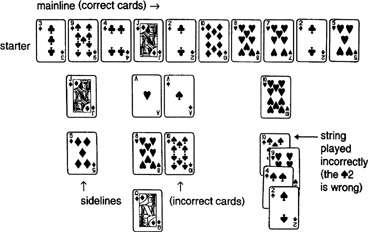

Play Each in turn tries to play a card to the mainline. If the dealer

says ‘Right’, it stays put and the player’s turn ends. If not, it is

replaced below the last card played in a ‘sideline’ extending at right

angles to the mainline. If a sideline already exists for that card, it

goes at the end of the sideline.

If you think you know The Rule, you can at empt to play a

‘string’ of two, three or four cards, of which you believe the first

correctly fol ows the last mainline card and the others correctly

fol ow that rule among themselves. Again, if the dealer says ‘Right’

they stay in place, but if ‘Wrong’ (and he won’t say how many or

which ones are wrong) they must be added to the latest sideline. In

this case they should be overlapped, to show that they were

at empted as a string and not one per turn.

When an at empt is declared wrong, and the incorrect card or

cards have been added to the sideline, the dealer deals to the

defaulting player twice the number of cards made in the at empt –

that is, from two to eight cards as the case may be.

Can’t play If you think you know The Rule, but have no card in

hand that wil go, you can declare ‘Can’t play’. In this case you must

hand that wil go, you can declare ‘Can’t play’. In this case you must

expose your cards so everyone can see them, and the dealer wil say

whether your claim is right or wrong.

If you’re wrong, the dealer must play to the mainline any one of

your cards that wil fit, then deal you five more from the stock.

What happens if you’re right depends on how many cards you

have left. If five or more, the dealer counts your cards, puts them at

the bot om of the stock, and deals you from the top of the stock a

number of cards equivalent to four less than the number you held

when you made the claim. If four or fewer, they go back into the

stock and the game ends.

Adding another pack If four or fewer cards remain in stock after

someone has been dealt more, shuf le them into the spare pack and

set it face down as a new stock.

The Prophet If you think you know The Rule, you may, instead of

simply playing al your cards out, seek to improve your eventual

score by declaring yourself a Prophet and taking over the functions

of the dealer (who, as the Ultimate Rule-maker, is known in some

circles as God). But there are four conditions:

1. There can only be one prophet at a time.

2. You cannot become a prophet more than once per deal.

3. At least two other players must stil be in play (discounting

yourself and the dealer).

4. You may declare yourself Prophet only when you have just

played a card (whether successful y or not), and before the

next in turn starts play.

On declaring yourself a prophet, you place a marker (such as a

coin) on the card you just added to the layout, whether or not on

the mainline, and stop playing your cards – but keep hold of them,

in case you get deposed and have to play again. You then proceed

to act as if you were the dealer, making the appropriate

announcementsof ‘Right’or‘Wrong’ as other players at empt to play.

announcementsof ‘Right’or‘Wrong’ as other players at empt to play.

The dealer must either confirm or negate each decision as you

make it, and you remain the Prophet so long as they are confirmed.

As soon as you make a wrong decision, you are deposed as Prophet,

are debited with a 5-point penalty, and must take up your hand of

cards and become an ordinary player again. The dealer takes over

again and immediately places correctly the at empted card or cards

that you wrongly adjudicated. Furthermore, whoever played them

is absolved from having to take extra cards even if their at empted

play was wrong.

Expulsion There comes a point at which it is assumed that everyone

has had long enough to deduce The Rule. Once that point is

reached, as soon as you make a play that is rejected as il egal you

are expel ed from the remainder of the deal, and place your cards

face down on the table. The expulsion point is reached when there

is no Prophet in operation and at least 40 cards have been played

to the mainline, or, if a Prophet is currently operating, at least 30

cards have been added to it since the Prophet took over. To keep

track, it helps to place a white piece on every tenth card from the

starter until a Prophet takes over, and then a black piece on every

tenth card from the Prophet’s marker. If a Prophet is overthrown,

the black pieces are removed and a white piece is placed on every

tenth card from the starter, but nobody can be expel ed on that

turn.

A round can go in and out of expulsion phases. For example, one player may

be expelled when there is no Prophet and more than 40 cards have been placed.

But if the next player then plays correctly and becomes a Prophet, and the player after that fails to place a card, the latter is not expelled, as fewer than 30 cards have been placed since the Prophet took over.

Ending and scoring Play ceases when somebody plays the last card

from their hand, or when everybody except the Prophet (if any) is

expel ed. Everybody scores 1 point for each card left in the hand of