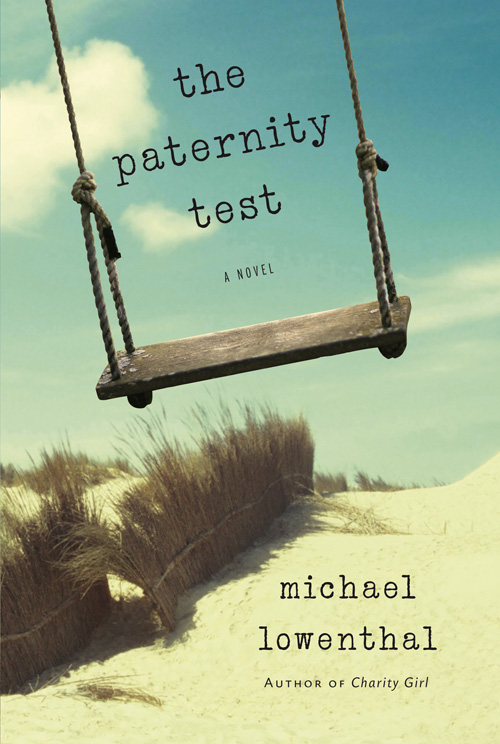

The Paternity Test

Read The Paternity Test Online

Authors: Michael Lowenthal

also by michael lowenthal

The Same Embrace

Avoidance

Charity Girl

the paternity test

michael lowenthal

terrace books

a trade imprint of the university of wisconsin press

Terrace Books, a trade imprint of the University of Wisconsin Press, takes its name from the Memorial Union Terrace, located at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Since its inception in 1907, the Wisconsin Union has provided a venue for students, faculty, staff, and alumni to debate art, music, politics, and the issues of the day. It is a place where theater, music, drama, literature, dance, outdoor activities, and major speakers are made available to the campus and the community. To learn more about the Union, visit

www.union.wisc.edu

.

Terrace Books

A trade imprint of the University of Wisconsin Press

1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor

Madison, Wisconsin 53711-2059

3 Henrietta Street

London WC2E 8LU, England

Copyright © 2012 by Michael Lowenthal

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any format or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews.

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lowenthal, Michael.

The paternity test / Michael Lowenthal.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-299-29000-9 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-299-29003-0 (e-book)

1. Gay men—Fiction. 2. Surrogate mothers—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3562.O894P38 2012

813′.54—dc23

2012009962

for my father

abraham lowenthal

cape codder by birth,

and for

mitchell waters

one

It’s not too late,” I said. “You could still change your mind.”

“What?” said Stu. “Now?” He glanced down at his watch. “Quarter till. They might already be there.”

We’d rumbled down the hill in our rust-corrupted Volvo, my parents’ “summer clunker” we inherited with the cottage. Now Stu turned and steered us through the narrows of 6A: past the shuttered ice-cream stand (“C U all next season!”), the barns with empty clamshell drives and sluggish whale-shaped vanes. Weathered shingles, the gull-gray sky, the browned, static marsh—the sober shades of Cape Cod in December.

But this was what I’d longed for: a hushed and dullish outback. I hadn’t set foot in New York since we’d moved.

“So call them,” I said. “Say you thought of a better place. It’s fine.”

With one sure hand, Stu veered to dodge a road-kill squirrel; the other hand was fidgeting with his scarf. “What kind of a first impression is that?” he said. “We can’t even commit to a

restaurant

?”

The Pancake King, where we were headed, had been his bright idea, overriding my suggestion of the Yarmouth House or one of our other surf-and-turf standbys. Someplace less expensive, he’d insisted: “Cheap enough so they’ll feel at home if they’re not used to fancy—or, if they are, maybe they’ll think it’s witty.”

He’d made a decent case, but it was just conjecture. We knew so very little about Debora and Danny Neuman, certainly not enough to safely judge what they might like. And yet here we were, crossing the Cape to meet them, to see if she’d agree to have our baby. Had ever there been an odder double date?

While Stu tossed and turned about the question of where to meet, I was trying to float atop the waves of my own worry: Would Debora and her husband see the patched-up, worthy Stu and Pat? Would any of our old frayings show?

I didn’t remind Stu—not in so many words—that it was he who’d pushed us toward a restaurant so silly. What I said (too carelessly) was, “Well, there’s always the Yarmouth House . . .”

“Perfect,” he said. “I knew you’d say ‘I told you so.’ I knew it!”

With a stagy crunch of gravel, he pulled to the shoulder and stopped. He stabbed the hazards button, got them clacking.

Stu was that incongruous thing, a Jewish airline pilot, and his manner could be just as oxymoronic. Forcefully indecisive, authoritatively whiny. With me, at least, in private, that could be his way. Strangers noted his rinsed-of-accent speech, his stringent crew cut, a gaze that seemed to own the whole horizon—the earned-in-sweat antithesis of a nebbish (a word he’d taught me). But late at night, or during sex, when Stu let down his guard, I could see his impressive eyes inch a smidgen closer, as though he wanted to stare at his own nose.

His eyes were like that now. I guessed they were, behind his Ray-Ban shades.

“Patrick,” he said. “Pat, hon. Be honest. You’re not nervous?”

The quaver of his humbled voice disarmed me. “Kidding?” I said. “Of course I am. I almost puked this morning.”

“Okay. And Debora and Danny—you think they feel the same?”

Considering what we’d ask of them, how could they not? I nodded.

“Right,” said Stu. “So, please, can’t you let

me

feel that, too?”

The world at large got Captain Stuart Nadler, at the stick. Who did I get? Someone neurotic about his choice of lunch spots.

“Just let me spaz a little,” he said. “It’s nothing. It’s routine turbulence. I mean, look at us. Look where we finally are!”

Where we were was a cattail-shaded stretch of silent road. Not a single car had passed since Stu had pulled us over.

I thought of an evening shortly after we had made the move, when I still worried he might quit and head back to the city; I had feared that our new life wouldn’t—that

I

wouldn’t—be enough. We went to see

Shrek 2

at the theater down in Sandwich, the lobby empty except for the wizened lady who took our tickets, who offered also to make a batch of popcorn. Stu, as the trailers started, looked around and whispered, “We can’t be, can we? The only people here?” He flung a kernel of popcorn at the screen. But then, after the lights went dark, seeing that we were indeed alone, he jumped up and took my hand and skipped us down the aisle, belting out the soundtrack in falsetto. Our own Kingdom of Far, Far Away!

Now, in the car, he removed his aviators. “Kiss me,” he said.

There

was the Stu I craved: my own top gun.

I followed his order, and tasted his familiarly foreign tongue: still, after a decade-plus, surprising in its saltiness.

“Ready?” he said, and revved the engine.

“I’ve

been

ready,” I said. “You know that.”

And so into the brackish Cape Cod bluster we charged, back on the road and off to the Pancake King to meet our womb.

A surrogate mother, at last! A woman who could give us what we couldn’t give ourselves.

I was thrilled, even if I’d hoped we’d get here sooner. How could we have wasted nine full months since we had moved?

Our first excuse for stalling—the one we’d dared to voice—had to do with all the stresses of taking over the cottage. On a ridge in West Barnstable, above the stylish dunes of Sandy Neck, the home was where we Faunces, for thirty-some years, had summered. Or, to follow Stu’s edict that

summer

was not a verb, the cottage was my family’s “summer home.” (Stu had tried, less successfully, to wean me off of

cottage

: with four bedrooms, two baths, a two-car garage, the house would be a mansion in Manhattan.) I had stayed at the cottage every school break as a kid, and since my parents had died, had co-owned it with my sisters, but suddenly it was mine alone—actually, mine and Stu’s—and suddenly, too, was meant to be the scene of our redemption.

All we’d known together was a queered-up city life: a life of sexual license, of looking the other way, our love stretched so thin it almost snapped; now we were nesting in this tranquil bayside home, having convinced each other that a baby would be the answer . . .

. . . and every domestic mishap gave a little karmic poke:

You really believe in happily ever after?

A clogged oil-burner nozzle. A leak in the chimney flashing. A bombardiering blue jay that mistook our picture window for the sky and left it smithereened with cracks.

The old poetry major in me couldn’t help but see the cottage in metaphorical terms. My answer was to make of the place a bold “objective correlative”: an external framework to stand in for—and influence?—our emotions. Thus came my compulsion to de-bramble ancient blueberry bushes that never, till just now, had called for rescue, and my early-morning passion for repointing decorative garden walls (the ones now made more visible by de-brambling).

In order to prove our readiness to raise a child together, I would get the place—and us—in unimpeachable shape.

Not that I minded the effort. In fact, I sort of loved it. As someone who wrote textbooks, shuffling words and phrases, getting the chance to grapple with actual objects pleased me greatly. More than that, I liked the work because it now was my work. At thirty-six, at last I had my private patch of earth.

My

work,

my

private patch of earth. But the house was also Stu’s now—or should have been, and had to be. And that required additional adjustments.

Stu insisted, rightfully, that he should make his mark upon the house, which basically hadn’t been touched since Mom had died. First to go was the sign—routered driftwood dangling from rusty chains—that had touted the property, ungrammatically, as “The Faunce’s.” Also tossed away were some dozen wall-hung photos, depicting scenes a great deal like (or maybe they were) our deck’s bay view; Mom had bought them, as if to claim her view as pictur

esque

she needed actual pictures for comparison. In their stead, Stu put up his raft of vintage travel posters. “Come to Ulster, the Holiday Wonderland, for a Real Change and Happy Days”; “Visitez L’Afrique en Avion.” He also set out keepsakes to remind him of New York: a coffee table whose surface was made of inlaid subway tokens; a sign from Yonah Schimmel’s: “Eat Knishes!”

Better, then. Much better. But still, sometimes, he told me, he felt like a hermit crab in some other creature’s shell. (It took all I had to keep from noting that his simile was proof of his becoming a Cape Codder.) “I watch you,” he admitted, one April Sunday morning, when I was sprawled on the living room’s shag carpet, doing a crossword. “The way you walk around from room to room. It’s like you’ve got your memories, this massive

net

of memories, throwing it over every inch, to claim things.”

True enough, and I wasn’t about to block those recollections. Even if I’d wanted to, I couldn’t.

The answer was to work on making memories now together, to co-star in our own all-new show.

Here we are, planting a row of rhubarb in the yard, dreaming aloud about the jams and chutneys we’ll cook up. In the house, we take the muslin, mollusk-patterned curtains down, replacing them with sleek bamboo shades. And, acceding to beachy norms, but also being camp, we park a homely trinket on the lawn: a whirligig whose plywood fisherman forever hooks a big one.