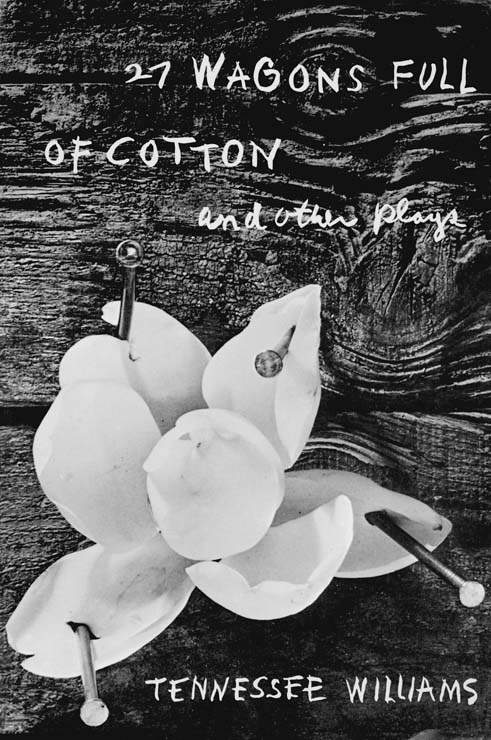

27 Wagons Full of Cotton and Other Plays

Read 27 Wagons Full of Cotton and Other Plays Online

Authors: Tennessee Williams

27 Wagons

Full of Cotton

AND OTHER ONE-ACT PLAYS BY

Tennessee Williams

A NEW DIRECTIONS BOOK

“Something wild . . .”

W

HILE

I W

AS

on the road with

Summer and Smoke

I was entertained one evening by the company of a successful community theater, one of the pioneer outfits of this kind and one of the few that operate on a profitable self-supporting basis. It had been 10 years since I had had a connection with a community theater. I was professionally spawned by one 10 years ago in St. Louis, but like most offspring, once I departed from the maternal shelter, I gave it scarcely a backward glance. Backward glances are a bit impractical, anyhow, in a theatrical career.

Now I felt considerable curiosity about the contact I was about to renew: but the moment I walked in the door I felt something wrong. Not so much something wrong as something missing. It seemed all so respectable. The men in their conservative business suits with their neat hair-cuts and highly polished shoes could have passed for corporation lawyers and the women, mostly their wives, were impeccably lady-like. There was no scratchy phonograph music, there were no dimly lit alcoves where dancing couples stood practically still, no sofas with ruptured upholstery, no garlands of colored crepe paper festooning the ceiling and collapsing onto the floor.

In my opinion art is a kind of anarchy, and the theater is a province of art. What was missing here, was something anarchistic in the air. I must modify that statement about art and anarchy. Art is only anarchy in juxtaposition with organized society. It runs counter to the sort of orderliness on which organized society apparently must be based. It is a benevolent anarchy: it must be that and if it is true art, it is. It is benevolent in the sense of constructing something which is missing, and what it constructs may be merely criticism of things

as they exist. I felt in this group no criticism but rather an adaptation which was almost obsequious. And my mind shot back to the St. Louis group I have mentioned, a group called The Mummers.

The Mummers were sort of a long-haired outfit. Now there is no virtue,

per se,

in not going to the barber. And I don't suppose there is any particular virtue in girls having runs in their stockings. Yet one feels a kind of nostalgia for that sort of disorderliness now and then.

Somehow you associate it with things that have no logical connection with it. You associate it with really good times and with intense feelings and with convictions. Most of all with convictions! In the party I have mentioned there was a notable lack of convictions. Nobody was shouting forâor againstâanything, there was just a lot of polite chit-chat going on among people who seemed to have known each other long enough to have exhausted all interest in each other's ideas.

While I stood there among them, the sense that something was missing clarified itself into a tremendous wave of longing for something that I had not been conscious of wanting until that moment. The open sky of my youth!âa peculiarly American youth which somehow seems to have slipped a little bit out of our grasp nowadays. . . .

The Mummers of St. Louis were my professional youth. They were the disorderly theater group of St. Louis, standing socially, if not also artistically, opposite to the usual Little Theater group. That opposite group need not be described. They were eminently respectable, predominantly middle-aged, and devoted mainly to the presentation of Broadway hits a season or two after Broadway. Their Stage was narrow and notices usually mentioned how well they had overcome their spatial limitations, but it never seemed to me that they produced anything in a manner that needed to overcome limitations of space. The dynamism which is theater was as foreign to their philosophy as the tongue of Chinese.

Dynamism was what The Mummers had, and for about five yearsâroughly from about 1935 to 1940âthey burned like one of Miss Millay's improvident little candlesâand then expired. Yes, there was about them that kind of excessive romanticism which is youth and which is the best and purest part of life.

The first time I worked with them was in 1936, when I was a student at Washington University in St. Louis. They were, then, under the leadership of a man named Willard Holland, their organizer and their director. Holland always wore a blue suit which was not only baggy but shiny. He needed a hair-cut and he sometimes wore a scarf instead of a shirt. This was not what made him a great director, but a great director he was. Everything that he touched he charged with electricty. Was it my youth that made it seem that way? Possibly, but not probably. In fact not even possibly: you judge theater, really, by its effect on audiences, and Holland's work never failed to deliver, and when I say deliver I mean a sock!

The first thing I worked with them on was

Bury the Dead,

by Irwin Shaw. That play ran a little bit short of full length and they needed a curtain-raiser to fill out the program. Holland called me up. He did not have a prepossessing voice. It was high-pitched and nervous. He said I hear you go to college and I hear you can write. I admitted some justice in both of these charges. Then he asked me: How do you feel about compulsory military training? I then assured him that I had left the University of Missouri because I could not get a passing grade in the ROTC. Swell!, said Holland, you are just the guy I am looking for. How would you like to write something against militarism?

So I did.

Shaw's play, one of the greatest lyric plays America has produced, was a solid piece of flame. Actors and script, under Holland's dynamic hand, were one piece of vibrant living-tissue. Now St. Louis is not a town that is easily impressed. They love music, they are ardent devotees of the symphony concerts, but they preserve a fairly rigid

decorum when they are confronted with anything off-beat which they are not used to. They certainly were not used to the sort of hot lead which the Mummers pumped into their bellies that night of Shaw's play. They were not used to it, but it paralyzed them. There wasn't a cough or creak in the house, and nobody left the Wednesday Club Auditorium (which the Mummers rented out for their performances) without a disturbing kink in their nerves or guts, and I doubt if any of them have forgotten it to this day.

It was The Mummers that I remembered at this polite supper party which I attended last month.

Now let me give you a picture of the Mummers! Most of them worked at other jobs besides theater. They had to, because The Mummers were not a paying proposition. There were laborers. There were clerks. There were waitresses. There were students. There were whores and tramps and there was even a post-debutante who was a member of the Junior League of St. Louis. Many of them were fine actors. Many of them were not. Some of them could not act at all, but what they lacked in ability, Holland inspired them with in the way of enthusiasm. I guess it was all run by a kind of beautiful witchcraft! It was like a definition of what I think theater is. Something wild, something exciting, something that you are not used to. Off-beat is the word.

They put on bad shows sometimes, but they never put on a show that didn't deliver a punch to the solar plexus, maybe not in the first act, maybe not in the second, but always at last a good hard punch was delivered, and it made a difference in the lives of the spectators that they had come to that place and seen that show.

The plays I gave them were bad. But the first of these plays was a smash hit. It even got rave notices out of all three papers, and there was a real demonstration on the opening night with shouts and cheers and stamping, and the pink-faced author took his first bow among the grey-faced coal-miners that he had created out of an imagination never stimulated by the sight of an actual coal-mine. The second play

that I gave them,

Fugitive Kind,

was a flop. It got one rave notice out of the

Star-Times,

but the

Post-Dispatch

and the

Globe Democrat

gave it hell. Nevertheless it packed a considerable wallop and there are people in St. Louis who still remember it. Bad plays, both of them, amateurish and coarse and juvenile and talky. But Holland and his players put them across the footlights without apology and they put them across with the bang that is theater.

Oh, how long ago that was!

The Mummers lived only five years. Yes, they had something in common with lyric verse of a too romantic nature. From 1935 to 1940 they had their fierce little flame, and then they expired, and now there is not a visible trace of them. Where is Holland? In Hollywood, I think. And where are the players? God knows. . . .

I am here, remembering them wistfully.

Now I shall have to say something to give this recollection a meaning to you.

All right. This is it.

Today we are living in a world which is threatened by totalitarianism. The Fascist and the Communist states have thrown us into a panic of reaction. Reactionary opinion descends like a ton of bricks on the head of any artist who speaks out against the current of prescribed ideas. We are all under wraps of one kind or another, trembling before the spectre of investigating committees and even with Buchenwald in the back of our minds when we consider whether or not we dare to say we were for Henry Wallace.

Yes, it is as bad as that.

And yet it isn't

really

as bad as that.

America is still America, democracy is still democracy.

In our history books are still the names of Jefferson and Lincoln and Tom Paine. The direction of the Democratic impulse, which is entirely and irresistibly away from the police state and away from any and all forms of controlled thought and feelingâwhich is entirely

and irresistibly in the direction of that which is individual and humane and equitable and freeâthat direction can be confused but it cannot be lost.

I have a way of jumping from the particular to the abstract, for the particular is sometimes as much as we know of the abstract.

Now let me jump back again: where? To the subject of community theaters and their social function.

It seems to me, as it seems to many artists right now, that an effort is being made to put creative work and workers under wraps.

Nothing could be more dangerous to Democracy, for the irritating grain of sand which is creative work in a society must be kept inside the shell or the pearl of idealistic progress cannot be made. For God's sake let us defend ourselves against whatever is hostile to us without imitating the thing which we are afraid of!

Community theaters have a social function and it is to be that kind of an irritant in the shell of their community. Not to conform, not to wear the conservative business suit of their audience, but to let their hair grow long and even greasy, to make wild gestures, break glasses, fight, shout, and fall downstairs! When you see them acting like thisânot respectably, not quite decently, even!âthen you will know that something is going to happen in that outfit, something disturbing, something irregular, something brave and honest.

The biologist will tell you that progress is the result of mutations. Mutations are another word for freaks. For God's sake let's have a little more freakish behaviorânot less.

Maybe 90 per cent of the freaks will be just freaks, ludicrous and pathetic and getting nowhere but into trouble.

Eliminate them, howeverâbully them into conformityâand nobody in America will ever be really young any more and we'll be left standing in the dead center of nowhere.

(

This introduction for the second edition of this collection first appeared in “The New York Star,” by the kindness of whose publisher it is here reprinted.

)