To Ruin A Queen: An Ursula Blanchard Mystery at Queen Elizabeth I's Court

Read To Ruin A Queen: An Ursula Blanchard Mystery at Queen Elizabeth I's Court Online

Authors: Fiona Buckley

Rave reviews for Fiona Buckley

and her Ursula Blanchard mysteries

“Buckley writes a learned historical mystery. Ursula, too, is a smart lass, one whose degrees must include a B.A. (for bedchamber assignations) and an M.S.W. (for mighty spirited wench).”

—USA Today

“Queen Elizabeth maintains a surprisingly vital presence … although it is Ursula who best appreciates the beauties—and understands the dangers—of their splendid age.”

—The New York Times Book Review

“Tantalizing.”

—Detroit Free Press

“Ursula is the essence of iron cloaked in velvet—a heroine to reckon with.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“Fantastic historical fiction filled with royal intrigue. … Fiona Buckley … makes the Elizabethan era fun to read about.”

—Midwest Book Review

“Fine writing and deft plotting … vividly [bring] the past to life. … [Buckley] effortlessly integrate[s] fact and fiction.”

—Publishers Weekly

(starred review)

Other Ursula Blanchard mysteries

Available from Pocket Books

The Siren Queen

To Shield the Queen

The Doublet Affair

Queen’s Ransom

And coming soon

Queen of Ambition

Ruin a Queen

An Ursula Blanchard Mystery

at Queen Elizabeth I’s Court

F

IONA

B

UCKLEY

| Pocket Books |

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2000 by Fiona Buckley

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Scribner Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

First Pocket Books trade paperback edition November 2008

POCKET and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-800-456-6798 or [email protected]

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ISBN-13: 978-1-4165-7353-1

ISBN-10: 1-4165-7353-4

eISBN-13: 978-0-7432-1365-3

This book is for John and Kerry,

without whom it would never have been written.

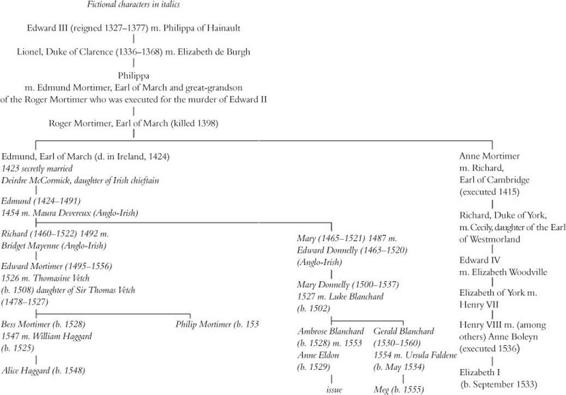

MORTIMER FAMILY TREE

The Power of Life and Death

The journey that took me from the Château Blanchepierre, on the banks of the Loire, to Vetch Castle on the Welsh March began, I think, on April 4, 1564, when I snatched up a triple-branched silver candlestick and hurled it the length of the Blanchepierre dinner table at my husband, Matthew de la Roche.

I threw it in an outburst of fury and unhappiness, which had had its beginnings three and a half weeks before, in the fetid, overheated lying-in chamber in the west tower of the château, where our first child should have come into the world, had God or providence been kinder.

I had begged for air but no one would open the shutters for fear of letting in a cold wind. Instead, there was a fire in the hearth, piled too high and giving off a sickly perfume from the herbs which my woman, Fran Dale, had thrown onto it in an effort to please me by sweetening the atmosphere.

The lying-in chamber was pervaded too by a continual murmur of prayers from Matthew’s uncle Armand, who was a priest and lived in the château as its chaplain. It was he who had married us, three and a half years ago, in England. To my fevered mind, the drone of his elderly voice sounded like a prayer for the dying. Possibly, it was. Madame Montaigle had fetched him after using pepper to make me sneeze in the hope that it would shoot the child out, and then attempting in vain to pull him out of me by hand, which had caused me to scream wildly. She told me afterward that she had despaired of my life.

Madame Montaigle was my husband’s former housekeeper. She had been living in a retirement cottage but she had skill as a midwife and Matthew had fetched her back to the château to help me. I wished he hadn’t for she didn’t like me. To her, I was Matthew’s heretic wife, the stranger from England, who had let him down in the past and would probably let him down again if given the ghost of a chance. I did not think she would care if I died. I would have felt the same in her place, but I could have done without either Madame Montaigle or Uncle Armand as I lay sweating and cursing and crying, growing more exhausted and feverish with every passing hour, fighting to bring forth Matthew’s child, and failing.

During the second day, I drifted toward delirium. Matthew had gone to fetch the physician from the village below the château but I kept on forgetting this and asking for him. When at last I heard his voice at the door, telling the physician that this was the room and for the love of God, man, do what you can, it pulled me back into the real world. I cried Matthew’s name and stretched out my hand.

But Madame Montaigle barred his way, exclaiming in outraged tones that he could not enter, that this was women’s business except for priest and doctor, and instead of pushing past her as I wanted him to do, he merely called to me that he had brought help and that he was praying to God that all would soon be well. It was the physician, not Matthew, who came to my side.

The physician was out of breath, for he was a plump man and Matthew had no doubt propelled him up the tower steps at speed. “I agree,” he puffed to Dale and Madame Montaigle, “that this is rightly women’s business. It is not my custom to attend lying-in chambers. However, for you, seigneur,” he added over his shoulder, addressing Matthew and changing to a note of respect, “I will do what I can.” He turned back to my attendants. “What has been done already?”

Madame Montaigle explained, about the pepper and her own manual efforts. Dale spoke little French and her principal task was to lave my forehead with cool water, smooth my straggling hair back from my perspiring face, and offer me milk and broth. The shutters made the room dim and the physician asked for more lights. I heard Matthew shouting for lamps. When they were brought, the physician, without speaking to me, went to the foot of the bed and began doing something to me; I couldn’t tell exactly what. I only knew that the pain I was in grew suddenly worse and I twisted, struggling. The physician drew back.

“The child is lying wrong and it is growing weak. Seigneur …”

Matthew must still have been hovering just outside the room, for the physician was speaking to him from the

end of my bed. He moved away to the door to finish what he was saying out of my hearing, and I heard my husband answer though I could not hear the words that either of them said. I called Matthew’s name again but still he wouldn’t defy convention and enter. I was left forlorn, bereft of any anchor to the world. I was dying. I knew it now. Here in this shadowed, stinking room, tangled up in sweaty sheets and with Uncle Armand practically reciting the burial service over me; before I was thirty years old; I was going to slip out of the world into eternity.

“I don’t want to die!” I screamed. “Matthew, I don’t want to die! I want to see Meg again!”

My daughter, Meg, was in England. I hadn’t seen her for two years and this summer, she would be nine. Now, a vision of her, as vivid as though she were actually there, filled my overheated mind. I saw her, playing with a ball on the grass outside Thamesbank House, where she lived with her foster parents. Her dark hair was escaping from its cap, and her little square face, so like the face of her father, Gerald, my first husband, was rosy with exercise. I could see the gracious outlines of the house, and the ripple of the Thames flowing past. For a moment, it was all so real that I called her name aloud, but the vision faded. She receded from me and was gone.

“If I die now I’ll never see Meg again and I’ll never see England again!” I wailed. “Somebody help me!”

“Hush.” Dale was in tears. “Don’t waste your strength, ma’am. Take a little warm milk.”

“I don’t want milk!” I flung out an arm in a frantic gesture of rejection and sent the cup flying out of Dale’s hand, spilling the milk on the trampled rushes and also

on Uncle Armand. “I want to give birth and get this over and I wish I’d never married again!”

Uncle Armand, brushing white spatters from his black clerical gown, said reprovingly: “Hush, madame. All things are according to the will of God. Women who die in childbirth may, I think, receive martyrs’ crowns in heaven.”

“I don’t want to be a bloody martyr!” I shouted at him. “I want to live!”

Peering through the lamplight and the red fog of my pain and fever, I saw the physician and Matthew anxiously conferring in the doorway. The fever seemed to have sharpened my senses for although the physician’s voice was still pitched low, this time I heard what he was saying.

“It is a son, seigneur, but there is little chance of saving him, I fear, and if I try, we shall almost certainly lose the mother. If we try instead to save her, the chance of success is better, but it will surely mean the child’s death. I cannot hope to save them both; that much is sure. It is for you to decide.”

I cried out, begging for my life. I had wanted Matthew’s child but in that moment it ceased to be real to me. Nothing was real except the threat, the terrible threat of extinction. Everything became confused. As delirium finally took over, I saw the physician come back to me but after that I remember very little. The pain became a sea in which I was drowning. Then came darkness.

When I became conscious again, I was still in pain but in a new, localized way. My body was no longer struggling. Its burden was gone. Dale and Matthew, very pale, were beside me and the physician stood

watchfully by. Uncle Armand and Madame Montaigle had left the room.