The Passport in America: The History of a Document (21 page)

Read The Passport in America: The History of a Document Online

Authors: Craig Robertson

Tags: #Law, #Emigration & Immigration, #Legal History

The State Department fits into this hesitant adoption of bureaucratic methods and new office technologies that were intended to facilitate an efficient, modern office environment. Through the nineteenth century and into the twentieth century, the department frequently relied on the memory of two long-serving officials, William Hunter and Alvey Adee. Their overlapping careers spanned ninety-five years, beginning with Hunter’s appointment as a clerk in 1829 and ending with Adee’s death in 1924 at the age of eighty-two. Hunter became second assistant secretary of state in 1853, a position formerly known as chief clerk that had been changed with the creation of the position of assistant secretary of state. He remained the department’s number three until his death in 1886, having worked for fifty-seven years under twenty-one secretaries of state. Adee, appointed to a temporary position in the State Department in 1877, succeeded Hunter and remained in that position until his death. Throughout their careers Adee and Hunter’s encyclopedic knowledge was regularly noted.

12

In the 1870s Hunter’s immediate superior described him as the “personification of the department’s work… its memory, its guiding hand.”

13

In one instance Hunter alerted the secretary of state

that a treaty the Dutch government had recently made a claim under had in fact been abrogated; in this instance it took considerable time to confirm his suspicion, as Hunter’s initial memory of the date proved inaccurate.

14

Although, Hunter’s memory, the State Department’s primary (re)collection of knowledge, was not always accurate through his almost six decades of service, it was critical in an office that until the 1870s lacked a bureau in charge of archives and collected its papers in chronological volumes, each with its own index. Adee took on a similarly crucial role, described in 1915 by a colleague as the “anchor of the State Department.”

15

His importance to the daily functioning of the department was recognized in the establishment of an Office of Coordination and Review in the State Department soon after his death. Although, as the personification of the department’s memory, Adee challenged the impersonality of the newer forms of bureaucratic administration one of his final wishes acknowledged the erasure of subjectivity critical to bureaucratic objectivity—he ordered all his personal papers burned at his death.

16

Particular individuals who possessed a broad knowledge of all that mattered in a government department, men who could claim impartiality and authority through personal reputation, became less critical to government as the prioritization of specialization and efficiency increased.

17

Thus, somewhat appropriately, Gaillard Hunt, who did much in his bureaucratic career to secure the history of the federal government in documentary form, began work in the State Department in 1887, a year after the death of Hunter. A decade later Hunt, then a passport clerk, completed the 233-page book

The American Passport: Its History and a Digest of Laws, Rulings and Regulations Governing its Issuance by the Department of State

. This book, including a detailed table of contents and an index, centralized the previously dispersed correspondence and memoranda on passport policy; it is primarily a collection of excerpts from the State Department’s external and internal correspondence, to which Hunt provided limited commentary.

18

Outside of this book the documents existed within the general State Department filing system based on bound volumes of correspondence created to store information, not to facilitate retrieval. While the digest as a collection of quotes had long been a model for codes of law, it is significant that the application of this format to U.S. passport policy occurred in a period in which the federal government was increasingly adopting bureaucratic practices in its day-to-day administration. Beyond its legal origins, the compilation of

The American Passport

signaled an attempt to produce knowledge

that was logical, rational, retrievable, and ultimately “reasonable.” The verification of precedent through retrieval no longer required personal knowledge of when and who wrote a letter or memo in order for it to be found in bound volumes. It simply required the clerk or official to read the book’s index. The book pared down the vast amount of passport correspondence to those extracts that critically Hunt and the current department believed mattered.

19

However, such innovations were only one aspect of the gradual emergence of bureaucratic practice. The year Hunt’s book was published, John Hay was appointed secretary of state. He arrived at a State Department described as an “antiquated, feeble organization, enslaved by precedents and routine inherited from another country, remote from public gaze and indifferent to it. The typewriter was viewed as a necessary evil and the telephone an instrument of last resort.”

20

Despite Hay’s overseeing such initiatives as the Passport Bureau, comments from his successor illustrate that introducing bureaucratic practices was no easy task. In 1905 Secretary of State Elihu Root described himself as “a man trying to conduct the business of a large metropolitan law-firm in the office of a village squire.”

21

A request for correspondence on any specific topic provided one source for his frustration. Because of the department’s record-keeping practices, any such demand usually led to the delivery of several large volumes, if indeed the requested documents could be located. Incoming and outgoing correspondence was stored in chronologically ordered bound volumes. Until 1870 records were indexed in the front of each volume. After 1870 the department made use of folio index books.

22

While these changes lessened the reliance on personal memory, the records themselves were still stored in multiple places. Reportedly annoyed at being brought several bound volumes after he requested a handful of documents, Root insisted a more efficient system of storage and retrieval be adopted.

23

In 1909 the department began to use a numerical subject filing system with the files stored in folders in filing cabinets; this was further refined by the introduction of a more comprehensive decimal filing system in 1917.

24

Innovations such as the filing cabinet and compilations like

The American Passport

provided a basis for a more impersonal and mobile memory that could be consulted in the absence of any specific individual; it facilitated the production of what Matt Matsuda labels the “memory of the state.”

25

These developments illustrate the “modern” recognition of the need for a systematic approach to information rather than the mere awareness of the

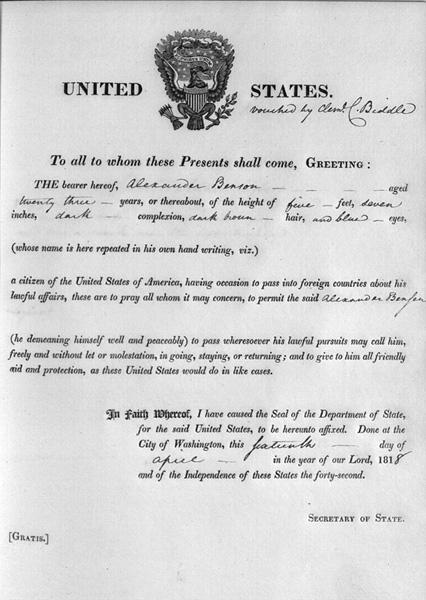

Figure 7.1. Copies of early passports were stored in a press book. This example from an 1818 volume shows that the file copy was used to note who had vouched for applicant (National Archives, College Park, MD).

need for information.

26

Akin to the move to use impersonal modes to verify identity, the demand for these techniques occurred in response to an increase in scale, specifically the volume of documents an office such as the State Department now produced. Information was organized so the state could have a memory over and above that of the individuals who worked in it. In most early nineteenth century large scale offices the memory of long-term workers (like Hunter and Adee in the State Department) had been required to locate relevant material on a topic because outgoing and incoming correspondence had been stored in two separate places. Incoming correspondence was usually stored in bound volumes and/or boxes, and copies of outgoing correspondence were created in tissue press books; in the first decades of the nineteenth century the State Department issued passports out of a press book (

figure 7.1

).

27

In each case documents were not indexed by subject but by author or destination, if at all. Initial attempts to store documents by subject in a centralized location through flat filing (pigeonholes and letter boxes) had limited success. In contrast the introduction of vertical filing solved these problems so successfully that it won a gold medal at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair; it ensured that after enabling officials to communicate, correspondence could become part of the state’s memory.

28

Rather than being a consequence of origin and chronology, storage could now be determined in anticipation of future use; carbon paper and typewriters assisted this development. With storage made more systematic the filing cabinet, combined with an appropriate indexing system, effectively increased the amount of readily available information on a particular subject by gathering all files on a topic in a location where, importantly, new files could be added easily. In making information available that had previously been hard to locate, the filing cabinet functioned to produce new knowledge.

The development of complex systems of filing played an important role in the first attempt to use documents to verify identity at the U.S. border as a result of the Chinese Exclusion Acts.

29

From the beginning of the twentieth century, extensive cross-referenced files centralized in Washington, D.C., were constructed as part of an attempt to improve channels of communication between the Bureau of Immigration and its agents at ports of entry; this attempt was also extended to State Department officials in China who issued documents to Chinese verifying their claim to be exempt from the act. The

systematic ordering of files was necessary because of the ongoing attempt to limit discretion and ensure predictability through an increasing reliance on procedures and documents. The turn to documents was a response to initial problems with the general enforcement of the act in the 1880s and 1890s and to specific instances of corruption.

The standardization of procedures, the documentation of decisions, and the centralization of records were more successful within the Bureau of Immigration in the United States than with the Asian-based diplomatic and consular service of the State Department. By the second decade of the twentieth century, with the prioritizing of structure and predictability, officials and clerks at the newly opened Angel Island immigration station near San Francisco were regularly rotated between cases in a further effort to limit personal attachment and emphasize the impartiality of the rules and procedures of the inspection system. In China the State Department had the most success in standardizing the methods of investigation that its representatives used to make Chinese people correspond to bureaucratically defined categories of exemption such as “merchant” or “student.” In this case the increasing use of documents was intended to remove both Chinese and officials from their local environment and relocate them into a centralized bureaucratic network. Except for the category of familial exemption, the social relations and interactions that usually defined an applicant’s identity were no longer relevant to the identity categories associated with Chinese exclusion. The act provided the identity that an official had to verify and the State Department generated a set of procedures to ensure this was done effectively and with a claim to objectivity; with this system of enforcement a migrant could only be a “merchant” if that identity could be verified through the appropriate standardized forms and cross-referenced files. In this scenario local Chinese were considered “interested parties,” in contrast to the purportedly bureaucratically neutral U.S. government officials whose attempts to enforce the act did not apparently come with any “interest.”

The attempt to create a bureaucratic system of predictability to manage Chinese immigration was frequently viewed as a clash of cultures between a modern, rational United States and an uncivilized, illogical China.

30

However, in the United States the hesitant development of the passport as a standardized identification document also led to a cultural clash when this rationalized administration encountered localized practices of trust and identification. In this manner the Chinese Exclusion Acts illustrates the formation of a documentary regime of verification, but the pervasive appearance of such a regime

in U.S. society cannot be explained without acknowledging the contested extension of documentation practices to the wider population. The passport as one of the first wider encounters with documentation is a critical example of how people initially responded to official identification. While the novelty of bureaucracy was challenged or only gradually accepted in the offices of business and government, such practices were more frequently perceived as foreign when they were applied to the identification of certain individuals; the objectivity critical to bureaucracy challenged the subjective claims long considered inherent to any authentic claim to identity, even the popular understanding of the legal category of citizenship. When a more rigorous documentation of identity was applied to marginal populations such as criminals and Chinese, it tended to make sense to the population at large, but it made much less sense to the larger population when they themselves became subjected to bureaucratic identification practices and found their word increasingly discounted. As previous chapters have noted, this marginalization of people’s opinion and socially produced reputation created for some a sense that the identity being asked for in the application and presentation of a passport did not necessarily belong to them. In issuing a passport in this manner, the State Department seemed interested in a distinct, if not altogether new, identity separate from people’s cultural and social understanding of who they were.