The ode less travelled: unlocking the poet within (25 page)

To conclude with the pair that started this excursion: in British English there is no rhyme for our voiced

with

, whereas the Americans can happily rhyme it with

pith, myth, smith

and so on. Weirdly we British

do

voice the ‘th’ of

with

in ‘forth

with

’ (but not for some reason in ‘herewith’). All of these pronunciations are, of course, natural to us. All we have to do is use our ears: but poets have to use their ears more than anyone else and be alive to all these aural subtleties (or ‘anal subtitles’ as my computer’s auto-correct facility insisted upon when I mistyped both words). Rhyming alerts us to much that others miss.

Feminine and Triple Rhymes

Most words rhyme on their

beat

, on their stressed syllable, a weak ending doesn’t have to be rhymed, it can stay the same in both words. We saw this in

Bo Peep

with

find

them/

behind

them. The lightly scudded ‘them’ is left alone. We wouldn’t employ the rhymes

mined gem

or

kind stem

.

Beat

ing rhymes happily with

meet

ing, but you would not rhyme it with

sweet thing

or

feet swing

. Apart from anything else, you would wrench the rhythm. This much is obvious.

Such rhymes,

beating/heating, battle/cattle, rhyming/chiming, station/nation

are called feminine. We saw the

melteth

and

pelteth

in Keats’s ‘Fancy’ and they naturally occur where any metric line has a weak ending, as in Shakespeare’s twentieth sonnet:

A woman’s face with Nature's own hand

paint

ed

Hast thou, the master-mistress of my

pass

ion;

A woman’s gentle heart, but not

acquaint

ed

With shifting change, as is false women’s

fash

ion;

And we saw feminine and masculine endings alternate in Kipling’s ‘If’:

If you can dream–and not make dreams your

mast

er,

If you can think–and not make thoughts your

aim

;

If you can meet with Triumph and Di

sast

er

And treat those two impostors just the

same

;

It is the stressed syllables that rhyme: there is nothing more you need to know about feminine rhyming–you will have known this instinctively from all the songs and rhymes and poems you have ever heard and seen.

As a rule the more complex and polysyllabic rhymes become, the more comic the result. In a poem mourning the death of a beloved you would be unlikely to rhyme

potato-cake

with

I hate to bake

or

spatula

with

bachelor

5

for example. Three-syllable rhymes (also known as triple-rhyme or

sdrucciolo

6

) are almost always ironic, mock-heroic, comic or facetious in effect, in fact I can’t think of any that are not. Byron was a master of these. Here are some examples from

Don Juan

:

But–oh! ye lords and ladies intellectual

Inform us truly, have they not hen pecked you all?

He learn’d the arts of riding, fencing, gunnery,

And how to scale a fortress–or a nunnery.

Since, in a way that’s rather of the oddest, he

Became divested of his modesty

That there are months which nature grows more merry in,

March has its hares, and May must have its heroine.

I’ve got new mythological machinery

And very handsome supernatural scenery

He even manages

quadruple

rhyme:

So that their plan and prosody are eligible,

Unless, like Wordsworth, they prove unintelligible.

Auden mimics this kind of feminine and triple-rhyming in, appropriately enough, his ‘Letter to Lord Byron’.

Is Brighton still as proud of her pavilion

And is it safe for girls to travel pillion?

To those who live in Warrington or Wigan

It’s not a white lie, it’s a whacking big ’un.

Clearer than Scafell Pike, my heart has stamped on

The view from Birmingham to Wolverhampton.

Such (often annoyingly forced and arch) rhyming is sometimes called

hudibrastic

, after Samuel Butler’s

Hudibras

(the seventeenth-century poet Samuel Butler, not the nineteenth-century novelist of the same name), a mock-heroic verse satire on Cromwell and Puritanism which includes a great deal of dreadful rhyming of this kind:

There was an ancient sage philosopher

That had read Alexander Ross over

So lawyers, lest the bear defendant

And plaintiff dog, should make an end on’t

Hudibras

also offers this stimulating example of

assonance

rhyming:

And though his countrymen, the Huns,

Did stew their meat between their bums.

Rich Rhyme

The last species worthy of attention is

rich rhyme

.

7

I find it rather horrid, but you should know that essentially it is either the rhyming of identical words that are different in meaning (

homonyms

)…

Rich rhyme is legal tender and quite sound

When words of different meaning share a sound

When neatly done the technique’s fine

When crassly done you’ll cop a fine.

…or the rhyming of words that

sound

the same but are different in spelling

and

meaning (

homophones

).

Rich rhyming’s neither fish nor fowl

The sight is grim, the sound is foul.

John Milton said with solemn weight,

‘They also serve who stand and wait.’

Technically there is a third kind, where the words are identical in appearance but the same neither in sound nor meaning, which results in a kind of rich eye-rhyme:

He took a shot across his bow

From an archer with a bow.

This rhyme is not the best you’ll ever read

And surely not the best you’ve ever read.

Byron rhymes

ours/hours, heir/air

and

way/away

fairly successfully, but as a rule

feminine

rich rhymes are less offensive to eye and ear for most of us than full-on monosyllabic rich rhymes like

whole/hole

and

great/grate

. Thus you are likely to find yourself using

produce/ induce, motion/promotion

and so on much more frequently than the more wince-worthy

maid/made, knows/nose

and the like.

A whole poem in rich rhyme? Thomas Hood, a Victorian poet noted for his gamesome use of puns and verbal tricks, wrote this, ‘A First Attempt in Rhyme’. It includes a cheeky rich-rhyme triplet on ‘burns’.

If I were used to writing verse,

And had a muse not so perverse,

But prompt at Fancy’s call to spring

And carol like a bird in Spring;

Or like a Bee, in summer time,

That hums about a bed of thyme,

And gathers honey and delights

From every blossom where it ’lights;

If I, alas! had such a muse,

To touch the Reader or amuse,

And breathe the true poetic vein,

This page should not be fill’d in vain!

But ah! the pow’r was never mine

To dig for gems in Fancy’s mine:

Or wander over land and main

To seek the Fairies’ old domain–

To watch Apollo while he climbs

His throne in oriental climes;

Or mark the ‘gradual dusky veil’

Drawn over Tempe’s tuneful vale,

In classic lays remember’d long–

Such flights to bolder wings belong;

To Bards who on that glorious height,

Of sun and song, Parnassus hight,

8

Partake the divine fire that burns,

In Milton, Pope, and Scottish Burns,

Who sang his native braes and burns.

For me a novice strange and new,

Who ne’er such inspiration knew,

To weave a verse with travail sore,

Ordain’d to creep and not to soar,

A few poor lines alone I write,

Fulfilling thus a lonely rite,

Not meant to meet the Critic’s eye,

For oh! to hope from such as I,

For anything that’s fit to read,

Were trusting to a broken reed.

II

Rhyming Arrangements

The convention used when describing rhyme-schemes is literally as simple as

abc

. The first rhyme of a poem is

a

, the second

b

, the third

c

, and so on:

At the round earth’s imagined corners, blow | a |

Your trumpets, angels; and arise, arise | b |

From death, your numberless infinities | b |

Of souls, and to your scattered bodies go; | a |

All whom the flood did, and fire shall o’erthrow, | a |

All whom war, dearth, age, agues, tyrannies, | b |

Despair, law, chance, hath slain, and you whose eyes | b |

Shall behold God, and never taste death’s woe. | a |

But let them sleep, Lord, and me mourn a space; | c |

For if, above all these, my sins abound, | d |

’Tis late to ask abundance of thy grace | c |

When we are there. Here on this lowly ground, | d |

Teach me how to repent; for that’s as good | e |

As if thou hadst sealed my pardon with thy blood. | e |

J

OHN

D

ONNE:

Sonnet: ‘At the round earth’s imagined corners’

This particular

abba abba cdcd ee

9

arrangement is a hybrid of the Petrarchan and Shakespearean sonnets’ rhyme-schemes, of which more in Chapter Three.

As to the descriptions of these layouts, well, that is simple enough. There are four very common forms. There is the

COUPLET

…

So long as men can breathe and eyes can

see

So long lives this, and this gives life to

thee

.

…and the

TRIPLET

:

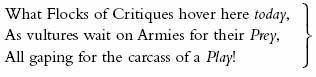

In the poetry of the Augustan period (Dryden, Johnson, Swift, Pope etc.) you will often find triplets

braced

in one of these long curly brackets, as in the example above from the Prologue to Dryden’s tragedy,

All For Love

. Such braced triplets will usually hold a single thought and conclude with a full stop.

Next is

CROSS-RHYMING

, which rhymes alternating lines,

abab

etc:

I wandered lonely as a

cloud

That floats on high o’er vales and

hills

,