The ode less travelled: unlocking the poet within (24 page)

Squat on my life?

Can’t I use my wit as a pitchfork

And drive the brute off?

Six days of the week it soils

With its sickening poison–

Just for paying a few bills!

That’s out of proportion.

The whole poem continues for another seven stanzas with loose consonantal para-rhymes of this nature. Emily Dickinson was fond of consonance too. Here is the first stanza of her poem numbered 1179:

Of so divine a Loss

We enter but the Gain,

Indemnity for Loneliness

That such a Bliss has been.

The poet most associated with a systematic mastery of this kind of rhyming is Wilfred Owen, who might be said to be its modern pioneer. Here are the first two stanzas from ‘Miners’:

There was a whispering in my hearth,

A sigh of the coal,

Grown wistful of a former earth

It might recall.

I listened for a tale of leaves

And smothered ferns;

Frond forests; and the low, sly lives

Before the fawns.

Ferns/fawns, lives/leaves

and

coal/call

are what you might call

perfect

imperfect rhymes. The different vowels are wrapped in

identical

consonants, unlike Larkin’s

soils/bills

and

life/off

or Dickinson’s

gain/been

which are much looser.

In his poem ‘Exposure’, Owen similarly slant-rhymes

war/wire, knive us/nervous, grow/gray, faces/fusses

and many more. His most triumphant achievement with this kind of ‘full’ partial rhyme is found in the much-loved ‘Strange Meeting’:

I am the enemy you killed, my friend.

I knew you in this dark: for you so frowned

Yesterday through me as you jabbed and killed.

I parried: but my hands were loath and cold.

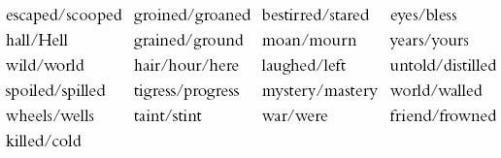

Here is the complete list of its slant-rhyme pairs:

All (bar one) are couplets, each pair is different and–perhaps most importantly of all–no

perfect

rhymes at all. A sudden rhyme like ‘taint’ and ‘saint’ would stand out like a bum note. Which is not to say that a mixture of pure and slant-rhyme is

always

a bad idea: W. B. Yeats frequently used a mixture of full and partial rhymes. Here is the first stanza of ‘Easter 1916’, with slant-rhymes in

bold

.

I have met them at close of

day

Coming with vivid

faces

From counter or desk among

grey

Eighteenth century

houses

.

I have passed with a nod of the

head

Or polite meaningless words,

Or have lingered awhile and

said

Polite meaningless words,

And thought before I had

done

Of a mocking tale or a

gibe

To please a

companion

Around the fire at the

club

,

Being certain that they and

I

But lived where motley is

worn

:

All changed, changed

utterly

A terrible beauty is

born

.

Assonance rhyme is suitable for musical verse, for the vowels (the part the voice sings) stay the same. Consonance rhyme, where the vowels change, clearly works better on the page.

There is a third kind of slant-rhyme which

only

works on the page. Cast your eye up to the list of para-rhyme pairs from Owen’s ‘Strange Meeting’. I said that all

bar one

were couplets. Do you see the odd group out?

It is the

hair/hour/here

group, a triplet not a couplet, but that’s not what makes it stands out for our purposes.

Hair/here

follows the consonance rule, but

hour

does not: it

looks

like a perfect consonance but when read out the ‘h’ is of course silent. This is a consonantal version of an

EYE-RHYME

, a rhyme which works visually, but not aurally. Here are two examples of more conventional eye-rhymes from Shakespeare’s

As You Like It

:

Blow, blow thou winter

wind

Thou art not so

unkind

…

Though thou the waters

warp

Thy sting is not so

sharp

It is common to hear ‘wind’ pronounced ‘wined’ when the lines are read or sung, but by no means necessary: hard to do the same thing to make the

sharp/warp

rhyme, after all.

Love/prove

is another commonly found eye-rhyme pair, as in Marlowe’s ‘Passionate Shepherd to his Love’.

Come live with me and be my

love

And we will all the pleasures

prove.

It is generally held that these may well have been true sound rhymes in Shakespeare’s and Marlowe’s day. They have certainly been used as eye-rhymes since, however. Larkin used the same pair nearly four hundred years later in ‘An Arundel Tomb’:

…and to prove

Our almost-instinct almost true:

What will survive of us is love.

In his poem ‘Meiosis’ Auden employs another conventional eye-rhyme for that pesky word:

The hopeful falsehood cannot stem with

love

The flood on which all move and wish to

move

.

The same poet’s ‘Precious Five’ shows that eye-rhyme can be used in all kinds of ways:

Whose oddness may provoke

To a mind-saving joke

A mind that would it

were

An apathetic

sphere

:

Another imperfect kind is

WRENCHED

rhyme, which to compound the felony will usually go with a wrenched

accent

.

He doesn’t mind the language being

bent

In choosing words to force a wrenched

accént

.

He has no sense of how the verse should

sing

And tries to get away with wrenched rhym

ing

.

A bad wrenched rhyme won’t ever please the

eye:

Or find its place in proper poe

try.

Where ‘poetry’ would have to be pronounced ‘poe-a-try’.

3

You will find this kind of thing a great deal in folk-singing, as I am sure you are aware. However, I can think of at least two fine

elegiac

poems where such potentially wrenched rhymes are given. This from Ben Jonson’s heart-rending, ‘On My First Son’.

Rest in soft peace, and asked say, ‘Here doth lie

Ben Jonson his best piece of poetry.’

Auden uses precisely the same rhyme pair in his ‘In Memory of W. B. Yeats’:

Let the Irish vessel lie

Emptied of its poetry.

I think those two examples work superbly, and of course no reader of them in public would wrench those rhymes. However, we should not necessarily assume that since Yeats and Jonson are officially Fine Poets, everything they do must be regarded as unimpeachable. If like me you look at past or present poets to help teach you your craft, do be alive to the fact that they are as capable of being caught napping as the rest of us.

Quandoque bonus dormitat Homerus

, as Horace famously observed: ‘sometimes even the great Homer nods’. Here is a couplet from Keats’s ‘Lamia’ by way of example:

Till she saw him, as once she pass’d him by,

Where gainst a column he leant thoughtfully

Again, a reader-out-loud of this poem would not be so unkind to poet or listener as to wrench the end-rhyme into ‘thoughtful-eye’. Nonetheless, whether wrenched or not the metre can safely be said to suck. The stressed ‘he’ is unavoidable, no pyrrhic substitutions help it and without wrenching the rhyme or the rhythm the line ends in a lame dactyl.

Where

gainst

a

col

umn

he

leant

thought

fully

Add to this the word order inversion ‘gainst a column he leant’, the very banality of the word ‘thoughtfully’ and the archaic aphaeretic

4

damage done to the word ‘against’ and the keenest Keatsian in the world would be forced to admit that this will never stand as one of the Wunderkind’s more enduring monuments to poesy. I have, of course, taken just one couplet from a long (and in my view inestimably fine) poem, so it is rather mean to snipe. Not every line of

Hamlet

is a jewel, nor every square inch of the Sistine Chapel ceiling worthy of admiring gasps. In fact, Keats so disliked being forced into archaic inversions that in a letter he cited their proliferation in his extended poem

Hyperion

as one of the reasons for his abandonment of it.

Wrenching can be more successful when done for comic effect. Here is an example from Arlo Guthrie’s ‘Motorcycle Song’.

I don’t want a pickle

Just want to ride on my motorsickle

And I’m not bein’ fickle

’Cause I’d rather ride on my motorsickle

And I don’t have fish to fry

Just want to ride on my motorcy…cle

Ogden Nash was the twentieth-century master of the comically wrenched rhyme, often, like Guthrie, wrenching the spelling to aid the reading. These lines are from ‘The Sniffle’.

Is spite of her sniffle,

Isabel’s chiffle.

Some girls with a sniffle

Would be weepy and tiffle;

They would look awful

Like a rained-on waffle.

…

Some girls with a snuffle

Their tempers are uffle,

But when Isabel’s snivelly

She’s snivelly civilly,

And when she is snuffly

She’s perfectly luffly.

Forcing a rhyme can exploit the variations in pronunciation that exist as a result of class, region or nationality. In a dramatic monologue written in the voice of a rather upper-class character

fearfully

could be made to rhyme with

stiffly

for example, or

houses

with

prizes

(although these are rather stale ho-ho attributions in my view).

Foot

rhymes with

but

to some northern ears, but then

foot

in other northern areas (South Yorkshire especially) is pronounced to rhyme with

loot

.

Myth

is a good rhyme for

with

in America where the ‘th’ is usually

unvoiced

. This thought requires a small explanatory aside: a ‘sidebar’ as I believe they are called in American courtrooms.

Voiced

consonants are exactly that, consonants produced with the use of our vocal chords. We use them for z, b, v and d but not for s, p, f and t, which are their

unvoiced

equivalents. In other words a ‘z’ sound cannot be made without using the larynx, whereas an ‘s’ can be, and so on: try it by reading out loud the first two sentences of this paragraph. Aside from expressing the consonant sounds, did you notice the two different pronunciations of the word ‘use’? ‘We

use

them for…’ and ‘without the

use

of…’Voiced for the verb, unvoiced for the noun. Some of the changes we make in the voicing or non-voicing of consonants are so subtle that their avoidance is a sure sign of a non-native speaker. Thus in the sentence ‘I have two cars’ we use the ‘v’ in

have

in the usual voiced way. But when we say ‘I have to do it’ we usually un-voice the ‘v’ into its equivalent, the ‘f’–‘I

haff

to do it. ‘He

haz

two cars’–‘he

hass

to do it’, ‘he

had

two cars’–‘he

hat

to do it’. When a regular verb that ends in an unvoiced consonant is put into the past tense then the ‘d’ of ‘-ed’ usually loses its voice into a ‘t’: thus

missed

rhymes with

list, passed

with f

ast, miffed

with

lift, stopped

with

adopt

and so on. But we keep the voiced -ed if the verb has voiced consonants,

fizzed, loved, stabbed

etc. Combinations of consonants can be voiced or unvoiced too: the ‘ch’ in

sandwich

has the voiced ‘j’ sound, but in

rich

it is an unvoiced ‘tch’; say the ‘th’ in

thigh

and it comes out as an unvoiced lisping hiss, say the ‘th’ in

thy

or

thine

and your larynx buzzes.