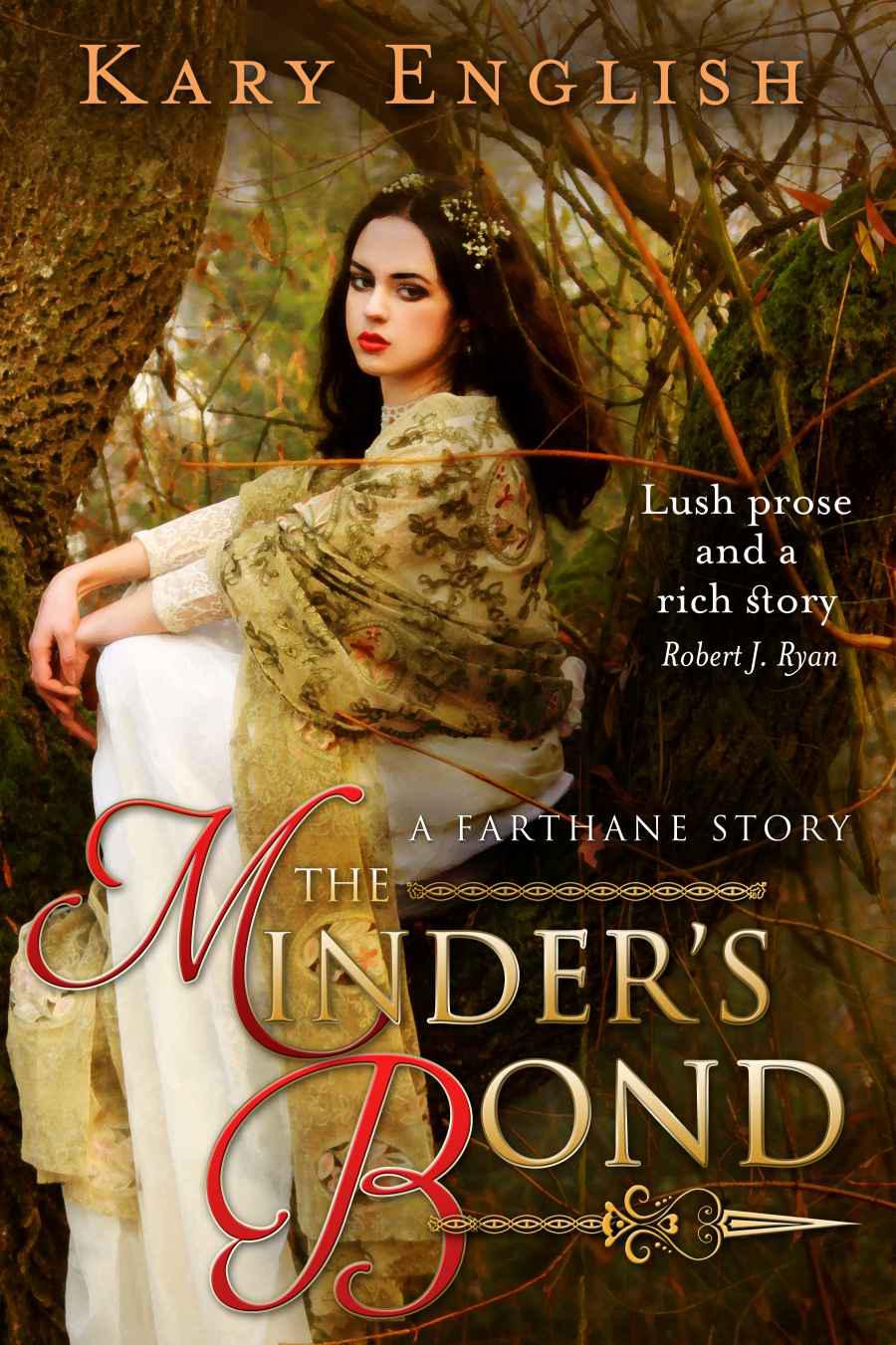

The Minder's Bond (Farthane Stories)

Read The Minder's Bond (Farthane Stories) Online

Authors: Kary English

by Kary English

W

hen I first beheld

the fabled port of Remidia, it was like something out of a tale. The city draped itself over the hills and valleys of the coastal range like a courtesan on silken cushions. White houses with bright tiled roofs adorned the hillsides like jewels at her throat.

More beautiful still was the blue of the

Southron Sea lapping at Remidia's shores. Balmy air coursed over my skin. The scent of salt air mingled with exotic spices.

If I had the power to remake the world, it would be this image of

Remidia that lingered in my mind instead of the brutal chaos that followed.

Marrec

, riding at my side, was speaking to me, but the first sight of the ocean's blue vastness drove his words from my mind. I had to look away from the white-fringed waves before I could answer.

"Caravan duty? I thought you said this was important?"

Marrec laughed. "For you, Finn Oxley, it is very important." Marrec slowed our pace to let the horses pass into the shade of a tree heavy with fruit. "Remidia's Publican is a man named Vicenna. His daughter Raimurri is a young Mender. I want you to guard her on our journey to Djefre."

Marrec

plucked two green globes from the tree. He kept one for himself and tossed the other to me. The fruit's leathery skin yielded under Marrec's teeth. He tore a strip away to reveal a fleshy center of indelicate pink.

"

Vicenna is highly placed in the ruling council. Do well, and you will gain his favor. Do poorly—" Here Marrec sucked the fruit's sweet pulp from its skin, then spat the bitter rind into the road where the horses trampled it into the dust. "—and you'll wish you'd never heard of Minders much less become one."

I'm not one to miss a warning, though I admit I was needled by it. I tossed the fruit back to

Marrec. "You may tell Vicenna that I am partial to the northern fruit of my upbringing." I fished an apple from my saddlebag and took a flamboyant bite. "So he needn't worry about my sampling the local delicacies."

I crunched for a moment before I continued. "Baby-sitting. Your star protégé. My first real mission, and you want me to play nursemaid on a caravan route that's safer than my grandmother's parlor?"

Marrec didn't rise to my banter. "Not with the drought in Cimya. We've had caravans attacked, drovers and children killed."

Marrec's

voice held a distant note, one that I recognized and didn't like. "You've seen something?"

Marrec

shook his head. "I know something. We've lost a full score of Menders and Judicars in the last six months. Someone is hunting our sister orders."

I whistled through my teeth. "Menders, too? Who'd want to kill a Mender?"

"Cimya, for one," said Marrec, "if they're spoiling for war. But this has the feel of something deeper, darker. The caravan attacks are a smokescreen. If there's trouble, get the girl to safety and leave the caravan to me. Understood?"

"You have my word," I said.

Supper at Remidia's Public House that night did homage to the sea. We dined on a covered patio, the walls open to the ocean breeze. Dark-eyed girls served us bowls of fragrant broth studded with sea creatures steamed in their shells, and a golden ale that tingled in the mouth.

I was wiping the bowl with a chunk of bread when

Vicenna joined us at the table with his daughter in tow. We stood to bow, and I remained politely silent while Marrec made our introductions.

The girl's eyes were brown as a winter doe's, as was her hair, which hung to her waist in a cascade of loose tendrils and fine braids laced with tiny gold beads. Earlier, her voice had lilted like a stream over pebbles when she greeted patrons or laughed at their jests. Here, though, she was stiffly silent, her back straight and her lips pressed into a line.

I bowed again when Marrec spoke my name. Raimurri's startled eyes flitted to my hair. The foxtail red was uncommon enough in my home village, but the looks I'd gotten here marked it as a spectacle.

"My daughter,

Raimurri daVicenna." Publican Vicenna gestured to the girl, whose rigid bob of a curtsy strained the bounds of politeness. "You will kindly forgive her," he continued smoothly. "She is apprehensive about the journey."

Raimurri

looked away from her father in silent negation. Her lips tightened further, and her hands on the tray she carried.

Apprehensive? I didn't think so. She looked angry. They'd argued, I guessed, with

Raimurri the loser. My hopes for an easy ride filled with pleasant conversation faded into disappointment.

At a signal from her father,

Raimurri served dessert while Marrec and Vicenna reviewed security precautions for the caravan. The bowl in front of me held a green fruit with the skin peeled back into four pointed petals. The pink sections had been teased apart like a hot-house flower, then drizzled with cream and honey.

Vicenna

excused himself, and Raimurri followed, the firelight glinting off the beads in her hair. When I picked up my spoon, I found that Marrec had stolen the fruit-blossom away.

"You," he said, placing a hard, green apple on the table in front me, "are partial to apples, remember?"

* * * *

We left

Remidia two days later. Coastal fog hung light and low in the valleys, and the sunny morning promised excellent weather for travelling. The passing wagons brushed the vegetation at the side of the road, filling the air with the scent of rosemary.

I kept my eyes on the blue-green hillsides. This helped me ignore

Raimurri, who rode at my side, and whose vigorous brushing of her long, dark hair helped her ignore me.

I'd greeted her with a polite word when the caravan assembled, holding up my hand with the fingers splayed in the gesture we Minders use to greet the ones we Mind. The barest touch of her fingertips would have strengthened my senses, tuning them to her above all others. Instead, I could see in the curl of her upper lip and the narrowing of her eyes that I might as well have offered her a handful of dung from the gutter.

"Let us understand each other, Mr. Oxley." She leaned close and kept her voice low. "Duty commands me to Djefre, but I am not a child. I don't need a nursemaid, and I don't need you."

I thought I was past being stung by the words of a girl, but the heat in my cheeks disagreed. "Duty, is it? Then you understand that I'll be guarding you whether you need it or not."

We'd mounted after that, me studying the scenery while Raimurri applied the brush to her hair.

* * * *

There was a jovial air in camp that night. The stars were bright, and the first hint of winter's chill made the fire seem cheerier by comparison. The drovers started a song about a recalcitrant mule that had everyone joining in for the chorus.

Vicenna's

generosity included fresh beef sizzling over the fire—my mouth watered at the smell—and several small casks of ale and cider. We'd be down to trail food by the end of journey, but tonight we were warm, well-supplied and enjoying the fellowship of the road. Even Raimurri seemed happy. That is, until she caught me watching her, which made her glare and look away.

The second day was much the same

—pleasant weather, easy riding, and proud-necked silence from Vicenna's dark-haired daughter. The hair brushing had become a daily ritual. Each morning when we mounted, she fetched out her rosewood brush, twisted her thin braids into a knot, then brushed out the loose tresses with long, languid strokes.

The process seemed meditative for her, as if her thoughts soared free while the brush was in motion. When she finished, she plucked the bristles clean and released the tangled strands into the air where they floated on the wind like fluff from a cottonwood tree.

That night, Marrec seated himself on one of the casks, refusing to let it be tapped until he'd rehearsed us all for next day's crossing of the Tirn River.

Raimurri

ignored me. Unused to sleeping rough, she'd looked rumpled and wan this morning.

Taking care to stay in

Raimurri's earshot, I asked one of the drovers how to pitch my tent for warmth. Then I shared my secret of blowing into one of the wide, flat waterskins the horses carried to make a pillow. Perhaps a good night's sleep and distance from her father might improve her disposition.

* * * *

Raimurri rewarded me the next morning, or so I thought, with the first willing words she'd ever spoken to me.

"Have you crossed the river before? Will we have to swim?" She didn't make eye contact, but her voice was carefully neutral and free of the resentment.

"Once. On the way here," I answered. "The current is too fast for swimming. We'll be crossing on the ferry."

"Ferry - you mean a boat?"

"More like a raft, a flat piece of dock that rides on ropes. Marrec wants us to hold back, go last. He's worried about trouble on the other side."

By mid-afternoon, we'd reached the river. We halted in the shade a hundred yards back.

Raimurri stood in the stirrups, craning her neck to see over the horses and wagons. Her mount sidestepped, unsettled by its agitated rider.

I felt a niggling pressure against my senses. Not a threat, but an unease that prickled the hair on the back of my neck.

I let my vision go soft, my eyes half-lidded. My danger-sense touched the river, the wagons, the surrounding landscape—nothing. The feeling stemmed from Raimurri herself. I took in her tense shoulders, her fingers twitching at the reins.

"

Raimurri, look at me." The command in my voice made her look before she could stop herself.

"What?" she asked.

"Can you swim?" I watched her with a Minder's gaze. Her reactions came in quick flashes. Wide, startled eyes. Flushed cheeks. A slight flare of her nostrils.

"I live on the ocean. Of course I can swim." She turned her back to me, stiff and proud once more.

A lie, then, or most of one.

When the last wagon boarded the ferry, I dismounted and drew a stick across the leading edge of a shadow on the ground. Six inches of afternoon shadow

—that's how long Marrec told me to wait.

Across the river, the caravan reassembled. The road climbed upward from the riverbed, so I could still see most of the wagons.

Raimurri's nervousness made her mount white-eyed. "We'll need to board on foot," I told her. "Water makes the horses nervous." It was my turn to lie, it seemed.

I offered my hand to help, though I wasn't surprised when she spurned it.

I reminded myself that duty was something one did because it was right and honorable, not because it was pleasant.

The ferry bobbed on the river ahead of us. It was made of strong planks nailed over round timbers and floating on barrels. It could hold two wagons with teams and crew, or maybe a hundred men if they stood close.

The logs underneath were worn smooth, and algae hung from the knots and crevices. The planking smelled of pine and new pitch. A handrail ran along the sides, and there was a drop gate at each end for easy boarding.

The platform wobbled as it took our weight. I barely noticed, but

Raimurri stood frozen on the deck. Her eyes darted to the rails. Too scared to approach the place where wood met water, she clung to her horse's stirrup instead.

The ferry lurched again as we edged into the current.

Raimurri stumbled; I steadied her. I was showing her how to loosen her knees to keep her balance when a flurry of activity on shore caught my eye.

Ragged men and women swarmed toward the caravan, throwing rocks and brandishing dull-looking weapons.

Marrec charged up and down the line shouting orders. I was proud of Remidia's soldiers, prouder still of the wagon-masters as each man snapped to his duty, hurling small bags of dried fruit, rice and beans into the onrushing mob. The amount was small, enough to feed a family for a night or two at most.

Several of the band stopped their charge, scrabbling in the dust to grab at the packages. We knew they were hungry, so we'd hoped the food would separate the desperate from the hardened criminals.

I ran to the bow of the ferry, clutching the rail in white-knuckled frustration. I wanted to be in the thick of the battle with Marrec, but my charge was Raimurri, who stood just behind me with her fists knotted in my sleeve.

My danger sense flared white-hot. I whirled to see what could possibly attack us mid-river and lost precious seconds to confusion. The answer

—a black-shafted arrow—buried itself in the shoulder of Raimurri's mount. I thrust her behind me, putting the wounded animal between us and the hidden bowman.

Two more shafts whistled through the air. One thudded into the wood of the rail. The other protruded from the throat of the screaming horse.

A glance at the distant riverbank told me all I needed to know—too much river, not enough cover.

I severed the rope that held the ferry's drop-gate closed. I grabbed

Raimurri in one hand, my horse's reins in the other, and plunged us into river's turgid waters. A slicing pain in my shoulder told me I'd been hit as we leapt.