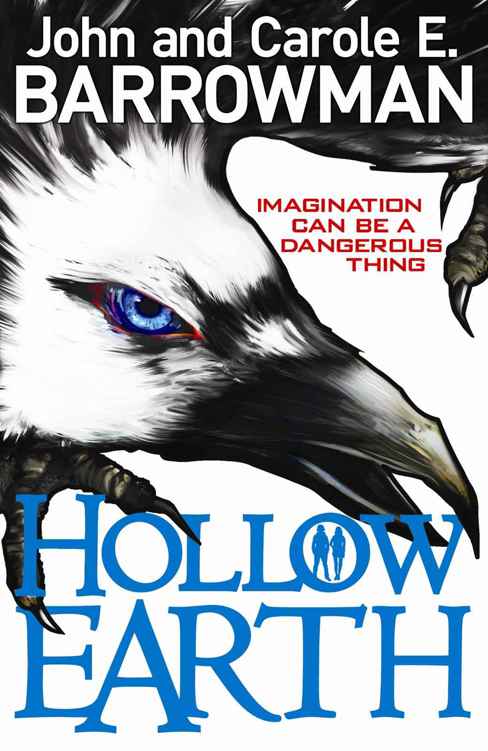

Hollow Earth

HOLLOW EARTH

‘In the universe, there are things that are known, and things that are unknown, and in between, there are doors.’

William Blake

First published in Great Britain in 2012 by Buster Books,

an imprint of Michael O’Mara Books Limited,

9 Lion Yard, Tremadoc Road, London SW4 7NQ

www.mombooks.com/busterbooks

www.hollow-earth.co.uk

Text copyright © John Barrowman and Carole E. Barrowman 2012

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Illustration copyright © Buster Books 2012

Illustrations by Andrew Pinder

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978–1–907151–64–4 in paperback print format

ISBN: 978–1–78055–084–8 in Epub format

ISBN: 978–1–78055–085–5 in Mobipocket format

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Designed and typeset by

www.glensaville.com

To Clare and Turner, Kevin and Scott, Marion and John, with love and thanks.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

John Barrowman is a presenter, a singer, a dancer and an actor, best known for playing Captain Jack in the television series

Doctor Who

and

Torchwood

.

Carole E. Barrowman teaches English and creative writing at Alverno College in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. She also writes for newspapers and regularly appears on television to talk about books. Carole and her brother have already written two books together, but

Hollow Earth

is their first novel for children.

Contents

PART ONE

ONE

The Monastery of Era Mina

Auchinmurn Isle

West Coast of Scotland

Middle Ages

T

he book the old monk was illuminating began with these words.

THIS Book is about the nature of beasts.

Gaze upon these pages at your peril

The old monk yawned, his chin dropped to his chest, and his eyes fluttered shut. The quill dropped from his fingers, leaving a trail of ink like tiny teardrops across the folio. He was working on one of the book’s later pages, a miniature of a majestic griffin with talons clutching the foot of an imposing capital G. As the old monk nodded off, the griffin leaped from its place at the corner of the page and darted across the parchment. In its haste to flee, the beast brushed its coarse wings across the old monk’s fingers.

The monk’s eyes snapped open. In an instant, he thumped his gnarled fist on to the griffin’s slashing tail, pinning the beast to the page. He glared at it. The griffin snorted angrily and scratched its talons deep into the thin vellum of the page. The monk shook off his exhaustion, focused his mind, and in a rush of colour and light the griffin was once again gripping the G at the top of the page.

Glancing behind him, the old monk spotted the bare feet of his young apprentice, poking out from under the wooden frame that held the drying skins to make parchment.

Something will have to be done,

the monk thought.

When he was sure the image was settled on the page, the old monk crouched to retrieve his quill. He was angry with himself. He would have to be punished for this terrible lapse in concentration and go without his evening meal. He patted his soft, round belly. He’d survive the loss.

But – the boy. What to do about the boy now, given what he’d witnessed? That loss would hurt. The old monk did not relish having to train another apprentice. He had neither the strength nor the inclination for such a task. Not only that, but this boy had already demonstrated a great deal of skill as a parchmenter, and was a natural at knowing how long to soak the skins in lime and how carefully to clean and scrape them. And, at such a young age, he was already an elegant calligrapher, and a brilliant alchemist with inks. Between the two of them these past months, they’d almost completed the final pages for

The Book of Beasts

. The boy and his talents would be sorely missed.

The boy sensed that the old monk was debating his future. He could hear the weight of the monk’s ideas in his head, like a drumming deep inside his mind. He associated the sound with the monk because at its loudest, when the monk was concentrating hardest, the drumming was deep and full and round, much like the monk himself.

The boy’s mother was the only other person the boy could sense in his head: a feeling not unwanted, although often peculiar. Not because he missed her. Far from it. His mother and his brothers and sisters still lived in the village outside the monastery gates. But his mother’s echo in his head had helped him escape her wrath, warranted or not, many times. Quickly, the boy lifted his pestle and mortar and finished crushing the iron salts and acorns for his next batch of ink.

The old monk straightened himself against his desk. What should he do? What if he were to fall asleep again while illuminating, only the next time his dozing was too sound? He didn’t dare think about the consequences of such a terrible slip. Only once before had he let such a thing happen, with tragic results. He’d been a young man and had not had the benefit of his training yet. In his nightmares, he could still hear the apprentice’s screams. Oh, and there had been so much blood.