The Last Stand of Fox Company: A True Story of U.S. Marines in Combat (22 page)

Read The Last Stand of Fox Company: A True Story of U.S. Marines in Combat Online

Authors: Bob Drury,Tom Clavin

Next they rummaged through the captured backpack. It contained a small bowl of frozen rice, a pair of steel-spiked boots too small to fit either of them, a tin of special rifle oil-whale oil?-for use in subfreezing temperatures, and a foldout brochure with photographs of people they assumed were Chinese dignitaries. The only face they recognized was Mao's.

At the bottom of the backpack was a crinkled photograph of its owner. He was posing in front of a pagoda in what looked like a big city with his wife and two children. They were all wearing Western clothes and smiling. Ernest and Freddy glanced from the photo to each other. Neither said a word.

Up at the two tall rocks the First Platoon's resituated light machine gun emplacement was down to four men. Corporal Dytkiewicz and Private First Class Gleason, who manned the gun, knew by now what had happened to Corporal Ladner's team the last time the Chinese had attacked. They expected no subtlety from their opponents. The Chinese would charge down the saddle, straight on and straight up, until they died.

The only cover for the machine-gun nest was some thin brush, and Dytkiewicz and Gleason shot envious glances at Ezell and Triggs frantically chipping out a hole behind the larger, more forward rock a few yards away. As the sky glazed purple in the west, almost to the color of a mussel shell, more "dead" enemy soldiers jumped up from snow holes and dashed across the saddle. The four Marines snapped off shots at these blurry figures while sniper bullets from the rocky knoll and the rocky ridges ticked through the branches around them.

"We either get 'em now or get 'em when they come later," Ezell yelled to Dytkiewicz. The corporal replied with a long burst that raked the ridgelines of Toktong-san.

At 6:05 p.m., Ezell flinched at a crunching of snow behind himbut he lowered his weapon when he recognized a Marine uniform. "Here," the Marine said, handing over eight hand grenades to be divided among the four-man crew. "It's all we can spare."

He had taken only a few steps back down the hill when he stopped and turned. "Listen," he said, "when you pull the pin, don't forget to pull the spoons up, too. They're probably frozen to the skin of the grenades."

At 6:30, a light snow began to fall. Ezell, Triggs, Dytkiewicz, and Gleason settled into what was technically a fifty-fifty watch. Although they were all exhausted, no one really slept.

Sometime around 7 p.m., Warren McClure woke from a deep sleep. He saw that he was still lying in the northeast corner of a sixteenby-eighteen tent, but something had changed. He was at such an angle that he felt he was about to slide down on top of the man below him. Then he remembered that the aid station had been moved and he was no longer on flat ground.

He looked around, wondering who had carried him here. Every square foot of the canvas tent floor was covered with wounded men. Most were suffering in silence, but many were in agonized positions. It was warm in the tent, the warmest McClure had felt in a long time, and he noticed pine branches burning in a portable kerosene stove near the tent's downhill flap.

Despite the heat McClure was in excruciating pain. Moving slowly, so as not to intensify what felt like the red-hot poker gouging into his chest, he began searching his pants and dungaree field jacket for his first-aid kit. In his right breast jacket pocket his fingers felt the morphine syrette that the corpsman McLean had left with him on the outcropping. He tore open the paper packaging and injected the tiny needle into his left wrist.

Someone-he couldn't tell who-pulled back the tent flap and announced that, according to scuttlebutt, a company of cooks and bakers was heading up the road from Hagaru-ri to relieve them. A smile creased McClure's face. Imagine what they'll say back at battalion. A line company of Marine riflemen rescued by the kitchen staff? Suddenly the pain was deadened and McClure nodded off into dreamless oblivion.

Dick Bonelli was certain this was a gag. He hadn't fired a machine gun since Pendleton and wasn't shy about letting Lieutenant McCarthy know it. The platoon commander had handed Sergeant Keirn's old light machine gun to one of the West Coast Marines, an Apache everyone called "Big Indian." Then McCarthy had tapped Bonelli as his assistant gunner. Bonelli thought that being assigned a dead man's gun was a bad enough omen. But then the lieutenant had ordered them to set up their nest out in front of the Third Platoon's forward line at the top of the hill. Like two sitting ducks.

They had barely dug in when it began snowing hard. As the flakes built up on the gun barrel, the Big Indian started shaking. At first Bonelli thought it was from the cold. Then he realized something was not right, and he wondered if it had to do with the fact that the Big Indian had been the only member of Wayne Pickett's fire team to avoid capture during the first attack. He was pondering just how, in fact, this had occurred when the Apache bolted from the hole with nary a word. Not a good sign.

Bonelli kept an eye out for his return as he sorted through the machine gun belts. Half of them, each holding a hundred or so bullets, had "crimped," or bent beyond repair, in their ammo boxes. He stacked these defectives toward the back of the foxhole while laying all the good belts, maybe half a dozen, within easy reach.

When he finished this housekeeping there was still no sign of his gunner, so he left the hole himself and made his way back to McCarthy's bunker command post. He found McCarthy and the Big Indian huddled around a single candle. The Apache had one lit cigarette in his mouth and another burning in his hand.

"What the hell's happening, Lieutenant?"

Bonelli was not one of Lieutenant McCarthy's favorite Marines. More than once McCarthy had to warn the wise-ass New Yorker to shape up or he'd be so deep in the brig they would have to shoot peas at him for chow. Now he just looked at Bonelli, exasperated.

"He can't make it," McCarthy said.

"Hell you mean he can't make it?"

McCarthy looked at Bonelli like he was three-quarters stupid. "I mean, he can't make it."

"Jesus Christ. The party's gonna start. Who's on the gun?"

"You got the gun," McCarthy said. "Get yourself an assistant. And when they come I'd better find you firing that gun or dead over it."

Bonelli took a last, disgusted look at the Big Indian, who would not return his gaze, and backed out of the dugout, fuming. The first foxhole he stumbled across was occupied by Private First Class Homer Penn of the Third Platoon-Penn from Pennsylvania, as everybody called him. Bonelli rapped him on the helmet. "You're coming with me," he said.

Penn from Pennsylvania cursed Bonelli during the entire trek up the hill. When they reached the machine-gun nest Penn eased himself into the foxhole as if there might be snakes inside.

At precisely 10 p.m., a loud series of beeps and electric feedback emanated from a loudspeaker set up under the lip of the west valley's deep ravine where it joined the saddle. A Chinese voice, speaking in perfectly enunciated English, explained that the Americans were surrounded and outnumbered, and their only rational course was to surrender. The man spoke patronizingly, as if he were addressing a classroom of particularly dull children.

A few Marines on the west slope caught an occasional glimpse of the Red behind the voice. He was tall and wore a full-length quilted coat with what appeared to be an officer's insignia on his shoulders and cap. They were maddening, these glimpses-too fleeting and coming from all about the shadowed ravine. It was as if the Chinese was aware of the Americans' desire to kill him and enjoyed playing this game of cat and mouse. He was too far away to reach with a grenade, and orders had been passed earlier among all Marines to save their little ammunition for a clear shot.

The enemy officer repeated his demand several times, and then the loudspeaker played Bing Crosby singing "White Christmas." When that ended, another song was played. It too was in English, but with a heavy accent. The chorus seemed to be, "Marines, tonight you die." When the music ended a huge bonfire erupted at the lee side of the rocky knoll, throwing into relief scores of moving, white-clad figures.

At 11 p.m., How Battery fired a white phosphorous shell from Hagaru-ri to register distance on the West Hill. The shell fell far short, and Gray Davis and Luke Johnson nearly jumped from their foxhole "all the way to Japan" when the round landed no more than ten yards in front of them. Unlike a howitzer shell, "Willie Peter" made no rustling whistle as it flew through the sky. The expanding shower of glowing, acrid-smelling, talclike orange particles filled the air around their hole. Both men were hit with chunks of the smoldering debris. Davis picked one up and studied it by the moonlight. The stuff was supposed to keep burning through anything it touched. Too damn cold to burn, he thought. Good thing.

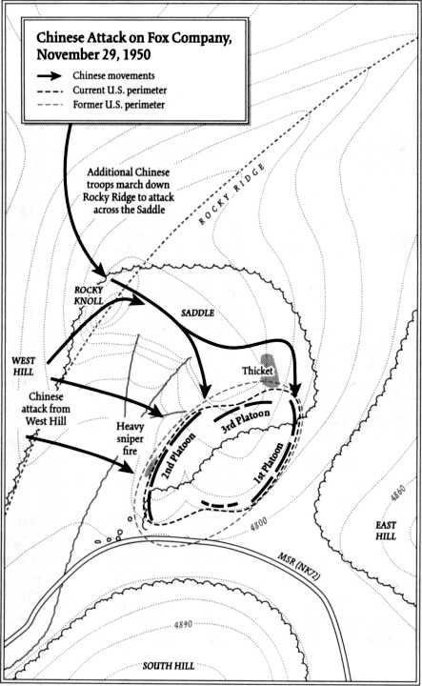

Thirty minutes later, their range corrected, How Company began an intermittent howitzer bombardment of the West Hill, the rocky knoll, and the rocky ridge. Fox Company's 81-mm mortar unit joined in, concentrating its fire on the rocky knoll and what the Marines were now calling the "sniper ridges" of Toktong-san.

It was almost midnight, and the four men manning the First Platoon's light machine-gun emplacement by the two tall rocks could clearly see many Chinese moving into and out of the light of the glowing bonfire. To Bob Ezell they looked like Indians performing a slow-motion war dance.

DAY THREE

NOVEMBER 29, 1950, 12 A.M-3 A.M.

6

Fox Company was hit by friendly fire at 2:15 a.m. when two artillery shells fell within the perimeter almost simultaneously. No one could tell whether they were launched from the howitzers at Hagaru-ri or the company's own 81-mm mortars.

The first exploded in one of the wide gaps along the Second Platoon's lines on the west slope, knocking a corpsman, McLean, against a tree but otherwise causing no harm. The second landed nearly on top of a Third Platoon foxhole just below the hilltop, killing one Marine and wounding two others, including the squad leader-the former seminary student Corporal Ashdale. The company's forward air controller told Captain Barber that the belowzero temperature had probably compressed the gases in the shells' propelling charges. Nothing could have been done; it was just a coldweather accident.

As the friendly fire demonstrated, the weather was affecting more than just Barber's men. A few days before heading up to the pass the captain and his communications officer, Lieutenant Schmitt, had noticed that as the artillery recoil mechanisms in How Company's howitzers froze, the cannoneers were forced to push the tubes back into the batteries by hand. This prompted Barber to order Schmitt to set up a temporary firing range outside the village to test the company s weapons.

The M1 rifles had handled the subfreezing temperatures better than the carbines. The gases in the smaller cartridges of the carbines had compressed in the cold, and their clips had failed to feed ammunition into the chamber. Schmitt experimented with various options, including stretching the gun's operating slide spring to give more force to the forward motion of the bolt. The results were inconclusive. The BARs also proved balky as the temperature dropped lower. But both the heavy and the light machine guns testfired adequately. Of course it was a hell of a lot colder up on Toktong Pass than it had been down at Hagaru-ri, as Jim Holt had discovered during last night's fighting when the water in the barrel jacket of his heavy machine gun froze solid.

Holt's gun crew had been forced to wait until sunrise, thaw the barrel, and substitute antifreeze. Corporal Jack Page did the same. The air-cooled light machine guns posed a different problem. The only way to prevent the carbon around the barrel tips from freezing up was to fire off a burst every hour or so. But cold, drowsy, lethargic men were likely to forget this task, and too often they were wary of giving away their emplacements. A couple of ingenious machine-gun crewmen hit on the idea of pissing on the barrels-if they were willing to expose themselves to enemy snipers.

The mortar crews also had difficulties. Their tubes' metal baseplates had to be relocated every few hours lest they freeze solid to the ground, and the baseplates were also beginning to show straining cracks from recoiling off the rock-hard hill. As for the grenade fuses, the men could only guess whether or not one would detonate after it was tossed.