The Last Stand of Fox Company: A True Story of U.S. Marines in Combat (17 page)

Read The Last Stand of Fox Company: A True Story of U.S. Marines in Combat Online

Authors: Bob Drury,Tom Clavin

Despite having taken back the hilltop, Barber ordered Lieutenant McCarthy of the Third Platoon to maintain his defensive perimeter where it had re-formed down the slope, about ten yards above the tree line. This would give McCarthy's men some cover from the snipers on the rocky knoll and high ridges of Toktongsan. Barber also realized that the Third Platoon was too depleted to dig in again and hold the entire crest. Preliminary casualty reports coming in to his command post indicated that McCarthy's outfit had been nearly halved.

8

Private First Class Ken Benson, wounded in the face by grenade fragments, groped blindly on his hands and knees.

"You passed out for a minute," said Hector Cafferata. "Nothing but dead Chinks is all you can see." He told Benson how he had noticed an enemy soldier's hand move in a pile of corpses not far from their hole and had bellied out to investigate. "Thought the guy was croaked by the time I get there. So I turn and I'm halfway back here and what's the bastard do? Heaves a grenade at me. Jesus. Thank God it was a dud. Went back out and put two in his head."

Benson was only half-listening. He knew he needed to get to the aid station. Ignoring Cafferata's offer to help, he started off on his own, crawling across the hill. He might have crawled all the way to Hagaru-ri had he not fallen into Private First Class Bob Ezell's foxhole near the First Platoon's light machine-gun emplacement on the upper east slope.

Ezell stuck a lit cigarette into Benson's mouth while Benson related the story of the "battle of the slit trench" in which he, Pomers, and Smith had emptied their rifles and sidearms into the Chinese charging across the saddle until their ammo was nearly gone. He described how Cafferata had batted grenades back with his entrenching tool, and how after being blinded he himself had squatted at the bottom of the freezing fucking foxhole reloading Hector's M 1 while what sounded like cannons blasted in his ears.

"It's really true," Benson told Ezell. "You lose one sense and the rest pick up the slack. After I couldn't see, everything else became so goddamn loud. My nose, too. Because I tell you, I smell coffee brewing somewhere."

Ezell stared at Benson in disbelief. He could smell no coffee, but the man was obviously not lying about being blind. Frozen blood caked both his eyes. Ezell wanted to rip off the bloody scabs but dared not. He was no corpsman. But batting potato mashers back in mid-flight with a shovel? Ezell had to wrap his mind around that one. Back in the States he'd been a pretty good hitter. But grenades? Well, he guessed it could be done.

Captain Barber, making rounds across the hill, happened by Ezell's post as Benson was relating his incredible story. For a moment the CO listened, rapt. He then instructed Ezell to help Benson down to the new aid station, the old mortarmen's tent at the bottom of the hill. Ezell, who like most of the First Platoon had missed the fight, was aghast at the number of dead Chinese he passed while guiding Benson down to the corpsmen. Halfway there Ezell picked up the scent of coffee brewing, too. When they reached the med tents someone handed Benson a steaming cup of joe. He didn't know whether to drink it or dip his freezing hands in it.

While Benson drank coffee, Barber ordered Ezell's light machinegun crew, commanded by Sergeant Judd Elrod, to pack up and move all the way over on the northwest crest, to the old emplacement between the Second and Third Platoons where Corporal Ladner's gun had been overrun and captured. This new experience-fighting the Chinese at night-had taught him a lesson. When they came again, Barber sensed, they'd come by the same route.

Where was everybody? Ernest Gonzalez awoke to bad thoughts, insane thoughts. His mind raced. He was alone on this hill. Everyone else was dead. He too would be dead soon enough. Should he fight? Surrender? Most of Fox Company had heard stories about the commie prison camps. How they bent your mind with drugs, or sleep deprivation, or maybe even the Chinese water torture. No, he decided, he would fight. He sat up and crawled from the slit trench. He heard gunfire down the hill, a bit to his left. A lone BAR, he thought. Somebody was shooting at something. He grabbed his M 1, checked the clip, and took off in that direction.

He edged over scores of dead Chinese soldiers, keeping low. Someone had defecated on the face of one of them. He half-ran, half-stumbled toward the sound of the gunfire. Bursting through a clearing in the trees he saw men. Marines. Alive. The shots he'd heard were from his own BAR man tearing up the saddle, shooting at stragglers. The BAR man turned toward Gonzalez. "Like qualifying on the range," he said.

Gonzalez thought of the rifle practice Barber had insisted on. Then, in a row of wounded Americans on blankets outside an aid tent, he spotted his fire team leader. Blood was leaking from both of his ears. Gonzalez did a double take. He was positive he'd seen this man die in his hole. No, he was alive too, all right-blown up from the two grenades, but alive. Jesus.

"We need ammo. Got any ammo?" A Marine was talking to him. Gonzalez snapped out of it.

Yeah, ammo, sure, back up in the slit trench. He turned and began climbing. He reached the trench and felt around under his sleeping bag. One lousy grenade. He searched the hole, and then the entire trench, for spare clips. There were none.

On his way back down Gonzalez fell in behind Sergeant Audas's detail clearing the crest. He stepped on a lump of-what? It was a Chinese soldier, curled into a fetal position facedown in the snow. The man had a wedge the size of a large slice of pie missing from the back of his head. Gonzalez could see his brain. He rolled him over and saw his eyelids flicker as irregular puffs of steam escaped his mouth. Gonzalez shot him in the chest. This was the last wounded man he would ever kill. He knew it wasn't exactly murder, but it was powerful, bad joss. He'd heard somewhere that joss was what the Chinese called luck.

Catching up to Audas's mop-up detail Gonzalez now came across a bloody Marine-issue sleeping bag at the bottom of a shallow foxhole. He unzipped the bag and discovered the body of Sergeant McAfee, bayoneted where he slept. Not far away he found the frozen body of the corpsman Jones, kneeling, with his hands between his knees, as if he had been executed. For some reason this sparked a memory: the snoring Marine, the fucker who had slept through the firefight. He wheeled and ran, hopped over his old slit trench, and found the foxhole. At the bottom of the ditch was a dead man with a gaping hole in his chest. So he wasn't snoring after all. The poor guy had been breathing through his sucking chest wound. The safety on the man's rifle was still on.

On his way back across the hilltop Gonzalez nearly stepped on another wounded Marine, still in his sleeping bag, bullet holes stitched across his stomach. He hollered for help and a corpsman appeared with a stretcher. They carried the man down to the new CP in the trees. Ernest Gonzalez gave the guy a pat on the head, turned, and took off up the hill searching for the Third Platoon's re-formed lines.

All night on the upper, northeast corner of the hill Corporal Eleazar Belmarez and two privates first class-John Scott and Lee D. Wilson -could only listen in frustration to the sounds of a firefight close by, just over on the far side of Fox Hill's main ridge. Their foxhole constituted the ultimate high left flank of the First Platoon's defensive line, separated from the right flank of the Third Platoon by the ridgeline's solid wall of gnarled granite and the tangled, impassable thicket.

Wilson was a decorated veteran of World War II, and at first he had not been happy to be paired with Belmarez, a new boot from San Antonio. From the moment they had begun digging in eight hours earlier Wilson grasped the tactical problem inherent in not being able to see their Third Platoon linkup, Corporal Koone's four-man fire team. It could make things dicey, and though Wilson knew and trusted Scott, he had no idea what size cojones Belmarez brought to the situation.

As they'd struggled to make a hole in the frozen ground, Wilson's ire rose when he saw his squad leader, Sergeant Daniel Slapinskas, along with Corporal Charles North, jump into an abandoned foxhole about ten yards down the slope to their right. The hole was chest-deep and must have been dug by the North Koreans during the summer, when a man could sink a shovel into this turf.

"Lucky bastards," he'd said aloud.

"Maybe, maybe not," Belmarez said as he'd jammed his spade into rock-hard turf like a jackhammer. "I'd rather be at the top. Higher ground, better fighting ground."

Maybe, thought Wilson, this kid will be OK. His black mood dissipated when Belmarez showed no sign of panic as they listened to the adjoining firefight.

Now, sometime just before 6 a.m., the snow had lightened to a fine white mist as Belmarez strode down the slope to Sergeant Slapinskas's hole and requested a recon mission. Slapinskas nodded and told him to take along the fourth member of their fire team, Corporal North.

The four Marines edged over the snowy ridgeline, keeping the thicket to their right. They were dumbfounded at the mounds of Chinese corpses. Belmarez and Wilson were the first to spot a Chinese soldier pop up from a snowhole and begin running, a light machine gun cradled in his arms. They had no way of knowing it had once belonged to Sergeant Keirn. All four fired and the man fell over. He was dead when they reached him. Wilson test-fired the machine gun. It worked fine.

As the four inched over the crest of the hill another Chinese soldier jumped from a pile of bodies. Wilson cut him down with the machine gun. At the rapid report of the gun, more Chinese began hopping up from scattered heaps of corpses and taking off toward the saddle. Wilson sprayed them, too, until each hit the ground. Were they dead? There was no sense in taking a chance. From that instant the First Platoon fire team administered a coup de grace to every prone body.

Not far from where Wilson had shot the first enemy soldier with the machine gun, three more Chinese rose to their knees, their hands in the air. Belmarez patted them down, noting that they were no more than kids. He ordered Private First Class Scott to take them back to Sergeant Slapinskas's hole. While they waited for Scott to return, Belmarez drew up a plan. They would circle the forty or so yards around the tangled thicket and emerge on the opposite slope of Fox Hill. This, Belmarez said, would give them a clear field of fire to the enemy bunched together on the rocky knoll. When Scott rejoined them and all four moved out, however, they discovered that even at the far corner of the thicket they still did not have a clear sight line to the rocky knoll, which was about 275 yards away.

Belmarez and Wilson, carrying the light machine gun and its bipod, crawled another fifty yards out. North and Scott covered them from the corner of the brush. Once out in the open, Wilson set up the machine gun and began raking the rocky knoll while Belmarez fed the belt. The Chinese at the base of the knoll fell or scattered. But the enemy soldiers on the higher ridgelines soon had a bead on Wilson and Belmarez, and a heavy volley of automatic weapons fire scorched their position.

Belmarez and Wilson dived into a shallow depression, sucked in air, counted to three, and sprinted back toward the thicket, still carrying the recaptured machine gun and its bipod. They fell in behind North and Scott, out of breath, laughing uproariously. Soon all four were convulsed in laughter. Wilson had seen this before, during the last war. It was a form of nervous release.

The caps of the lonely, undulant mountains glowed ruddy one after the other as the angled sun rose slowly on the eastern horizon, its rays reflected blindingly off the snow. Gray Davis could hear wounded Chinese soldiers moaning and praying in the valley separating his hole from the West Hill. At least he thought some were praying-they sounded very different from the yelping cries of the men who still wanted to live. He and Luke Johnson were almost out of ammo again. In covering the stretcher bearers who had dragged Jack Griffith away, they had used most of what Griffith had retrieved. Davis told Johnson he was going to go scare some up.

He crawled over the lip of their foxhole and out into the valley close to where it met the road, trying to keep in among the scrub that ran down to the pile of five big rocks. He was struck-as were so many Marines on Fox Hill-by the grotesque forms of the fro zen dead. He was also impressed by the efficiency with which the Chinese had policed the battlefield. He couldn't find a gun or a box of cartridges to save his life-and now that he thought about it, that had become more than just a cliche.

Then Davis heard whimpering beyond a small, two-foot hump farther out in the valley. He "breast-stroked" about thirty yards through the foot-deep snow until he was face-to-face with a wounded enemy soldier. He was out in the open now, closer to the West Hill than he preferred. Through half-lowered eyelids the dying man-such a little guy-looked at Davis and attempted to extract a potato masher from his quilted jacket pocket with fingers that were frozen and swollen. Davis rose to his knees and shouldered his M I. The snow around him exploded with bullets from the West Hill.

Davis hit the ground and watched for another long moment, almost hypnotized, as the man continued to fumble for the grenade. Then he spotted a Belgian-made automatic rifle and a box of bullets a few yards away. He stood and ran, zigzagging at top speed back to his line, barely breaking stride to scoop up the rifle and ammo. Slugs snapped past his head and thudded into the snow around his feet. Luke Johnson laid cover fire across the slopes of the West Hill. Davis fell into the foxhole, broke open the cardboard box, and began divvying up the cartridges.

9

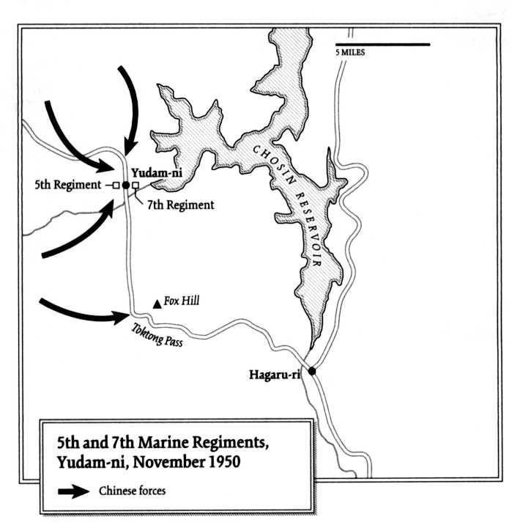

Up at the Chosin Reservoir, Colonel Homer Litzenberg had concluded that the Seventh Regiment's best chance for survival was strength in numbers. Twelve hours earlier he had had eighteen rifle companies at his disposal, ready to push on to the Yalu. They were now down to a battered fifteen-with two of those surrounded on hills several miles away, their future effectiveness in doubt. Litzenberg had to find a way to reunite Fox with his remaining forces at Yudam-ni.