The Last Stand of Fox Company: A True Story of U.S. Marines in Combat (18 page)

Read The Last Stand of Fox Company: A True Story of U.S. Marines in Combat Online

Authors: Bob Drury,Tom Clavin

He reached Barber by radio as the captain was overseeing the erection of the new company command post tent about fifty yards east of the shallow gully that ran up the center of Fox Hill. Litzenberg asked Barber his thoughts about quitting the hill and fighting his way north.

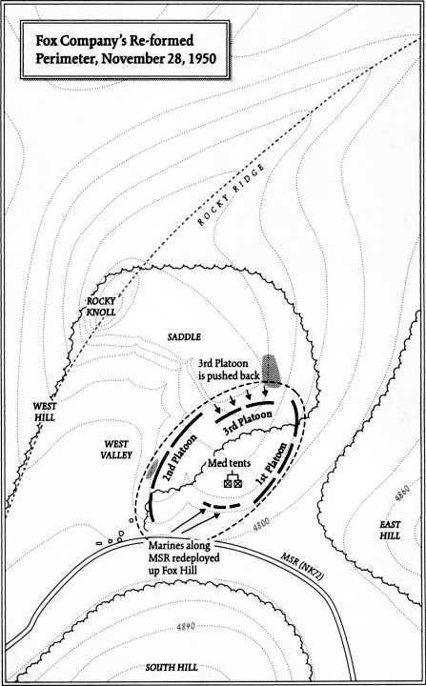

Barber had been worrying this bone for a while, and he considered the idea impractical in the extreme. He had taken too many casualties to move anywhere, and his ammunition stores had nearly run out. Lieutenant Peterson reported that his Second Platoon was down to between three and six bullets per man. Moreover, his small band of Marines was the only obstacle holding open the back gate from the Chosin. If the Chinese took these heights there was little chance Litzenberg's troops would get out alive.

The captain kept that thought to himself, however, and without explicitly citing the number of his wounded, lest any Chinese monitoring their radio frequency overhear, he indicated to Litzenberg by mentioning "tactical necessities" that he could not abandon his position.

Litzenberg's cryptic reply signaled that he understood Barber's meaning and intent, and before signing off Barber ended the exchange on an upbeat note. Just get us some airdrops, he said, ammo and food, especially grenades-and we'll hold this piece of real estate until the enemy drops from exhaustion.

Litzenberg could do better than that. Following his conversation with Barber he immediately radioed Lieutenant Colonel Lockwood in Hagaru-ri and ordered the formation of a composite force from the Marines remaining in the village-cooks, bakers, clerks, drivers, and communications and intelligence people. He wanted every soldier in Hagaru-ri with the exception of the artillery gunners and a small rear guard to get up that road and reinforce Fox. It was time to implement the Corps rule "Every Marine a rifleman." He called Barber back to tell him that relief was on the way.

After dropping Ken Benson at the aid station, Bob Ezell returned to his light machine-gun emplacement on the east side of the hill. The crew was gone. He asked around and learned that Captain Barber had ordered the gun dug in between the Second and Third Platoons on the northwest crest near the two tall rocks. Ezell had never been on that side of the hill, and it took him several minutes to orient himself and crawl across the crest. He used the scores of Chinese corpses as cover from the constant sniping; there were so many they reminded him of sagebrush in the desert.

He had just spied the two giant domino-like rocks a little above him when someone came tumbling down the hill. Sergeant Judd Elrod practically rolled into his arms. He had been shot in the same hip that had taken a Japanese bullet seven years earlier at Tarawa. But the force of the impact had been blunted by his binoculars case. Elrod, who had also been wounded in the fighting around Seoul, handed Ezell his smashed binoculars. "Ain't gonna do me any good," he said.

Ezell noticed that one of the glass eyepieces was shattered. He bent to help Elrod up, but the sergeant waved him off.

"Get your ass up to the emplacement," he said. "I can get down to the med tents by myself."

By the time Ezell reached the light machine-gun nest yet another Marine was down. Private First Class Dick Bernard, an ammo carrier, had been hit twice within ten minutes by sniper fire. The first bullet grazed his right leg. The second broke his left femur. Ezell barely had time to take in the situation before someone yelled, "Duck-he's got a grenade."

Ezell wheeled and spotted a Chinese soldier emerging from a depression thirty yards away, where the deep ravine running up the west valley met the saddle. The man had a long, stringy mustache that fell below his chin; he reminded Ezell of the evil mastermind Fu Manchu in the movies. He instinctively put three slugs into the man's chest. It was the first time Ezell had fired his rifle since Camp Pendleton. A moment later, two full enemy squads charged from the same depression. The machine gun knocked over about half of them and the rest dropped their weapons, threw up their hands, and surrendered. Ezell figured they must have been short a po litical commissar. One Marine wanted to shoot them, but another didn't like that plan: "If we shoot 'em, nobody else will ever surrender."

So the prisoners were rounded up and led down to Captain Barber's tent. Once again the Americans were struck-and disgusted -by how young the Chinese seemed. Who the hell is sending fifteenand sixteen-year-old kids out to fight a man's war?

A corpsman, carrying a rolled stretcher, passed the enemy prisoners and their Marine guards as he ran up the hill. Ezell noticed that the sniping trailed off considerably while the Chinese were in the open area between the two tall rocks and the tree line. As soon as they disappeared into the woods, however, it picked up again. If he'd known that was how their minds worked he would have made the Chinese carry Dick Bernard down to the med tents. Instead, using the rocks as cover, the light machine-gun crew rolled the private onto the litter and Ezell joined the corpsman and two more Marines at the corners. They counted to three and took off, running as fast as they could and nearly bouncing Bernard right off the canvas stretcher.

Near the command post Ezell bumped into Freddy Gonzales. Freddy was Roger Gonzales's cousin, and Roger and Ezell had played summer ball in San Pedro. But Roger's real forte had been track and field. He was a thirteen-foot pole-vaulter and a low-twominute half-miler. Before the war Ezell and Roger Gonzales had shared their secret hopes: making the major leagues and competing in the Olympics, respectively.

"What do you hear from Roger?" Ezell said.

Freddy Gonzales lit a cigarette and scuffed the snow with the toe of his shoepac. "KIA during the night."

THE SIEGE

DAY TWO

NOVEMBER 28, 1950 6 A.M.-MIDNIGHT

1

At 6 a.m. the Marines strung up and down the hill unofficially declared the first night's battle for Fox Hill over. The action at the Sudong Gorge had been a vicious skirmish, but still only a skirmish. Now Fox Company had engaged in a full-scale firefight with Chinese Communists for the first time and had held their own.

The snow had stopped falling and pale sunlight streamed through the smoky scene as now and again another "dead" enemy soldier would rise like a ghost and scamper back across the saddle toward the rocky knoll. Sometimes a Marine would pick him off; sometimes he would make it. Intermittent sniper fire from the ridges and folds of the West Hill and the ridges of Toktong-san continued, and two Americans were wounded by a burst of automatic fire at 6:07 a.m. But for the most part both sides were content to use the daylight hours to lick their wounds and regroup.

Men hopped from their foxholes and began dragging Chinese bodies to use as sandbags. Although there were fewer enemy dead on the west slope of the hill, Bob Kirchner managed to find half a dozen corpses to pile in front of his hole, including the two men he had bayoneted and the bugler Sergeant Komorowski's grenade had beheaded.

To his everlasting sorrow, he also dragged Roger Gonzales's body out of his hole and added it to the stack. He was sure the dead Marine would have understood; Kirchner certainly would have if the tables were turned.

Up at the two tall rocks Captain Barber directed Bob Ezell's machine-gun crew, now down to four men, to register several white phosphorous rounds-"Willie Peter"-lofted toward the rocky knoll and the rocky ridge by the 81-mm mortars. The shells were not very effective because the small mushroom clouds, with their white, spindly spider legs, did not contrast with the snow. Meanwhile, Marines across the hill began scrounging among the enemy corpses. They were amazed to find U.S. Navy-issue field glasses and Americanmade Palmolive soap, Colgate toothpaste, and Lucky Strike cigarettes. Many of the captured packs and knapsacks also held small picks and shovels. After the firefight the Americans, who now understood the danger they faced, found it miraculously easier to dig into the frozen ground.

But the most stunning discoveries were the guns and ammunition. They ran a global gamut, and the recovered weaponry flabbergasted the Americans. There were a dozen or so Thompson submachine guns, the "Chicago typewriters" that the United States had shipped to Chiang Kai-shek by the boatload during World War II and the Chinese civil war. To these were added aluminum Russian burp guns, Japanese automatic rifles, British Lee-Enfields and Stens, American Springfields, and several ancient wooden rifles of indeterminate origin. Numerous khukri blades, knives carried by generations of Ghurka infantrymen, were also turned up, and the late Corporal Ladner's light machine gun was discovered half-buried in the snow near the lip of the ravine running up the west valley. Finally, Lieutenant McCarthy ordered his men to take the weapons and ammo from any dead Marines, a particularly unpleasant task.

At 8 a.m., Ezell was one of the Marines sorting through the captured weapons on the hilltop when he saw Hector Cafferata crawling in his socks out onto the saddle toward the listening post he had escaped six hours earlier. Ezell could only imagine how awful the big man's feet must have felt as he slithered into the hole and bent down to gather his gear and shoepacs. As soon as he stood he was knocked down again by a sniper bullet. Ezell dived into a trench and called out to him, but Cafferata merely let loose a torrent of curses and oaths. Shit-shit-fuck-shit. Fuckinggoddamn sniper. Motherfucking fucker.

Ezell yelled again. "Hector! Is it bad?"

Between curses Cafferata waved at him to keep down. "I can make it!" he hollered.

Cafferata had no way of knowing that the bullet had pierced his right shoulder, ricocheted off a rib, and punctured his lung. What he did know was that he was in agony-the pain was so great that he did not even know where, or how many times, he'd been hit. His chest felt as if it had been run through by a spear, and his groin was on fire. He assumed they'd also gotten him in the balls. When he reached down with his good right hand his underwear was pooling with blood. He could not feel his testicles. That's it, he thought. No kids for me. A wave of remorse washed over him as he undid his web belt, fashioned a sling, and lurched down the hill.

The Americans down near the road were also stirring from their foxholes and defensive positions. Corporal Robert Gaines was venturing down from Private First Class Holt's heavy machine-gun nest-the gun was finally unfrozen-when he heard a combination of voices and moans from the large hut adjacent to the MSR. He peeked through a bullet hole in the planking and saw at least a squad of wounded Chinese on the dirt floor. He pulled the pins on two grenades, tossed them inside, and ran back up the hill.

Not long afterward Corporal Harry Burke of the bazooka section and a corpsman arrived at the same hut. Burke was hoping to retrieve the sleeping bag he'd stowed in the large cooking pot when he'd first arrived on the hill. Gaines's grenade had left two Chinese still alive, though badly torn up. The light brown color of their frozen flesh reminded Burke of wax dummies. He and the corpsman put them out of their misery with sidearms, and Burke found his bag right where he had left it. Everything else, however, was gone. Shoepacs, parkas, and packs had been carried away in the night.