The Hundred Years War (25 page)

Read The Hundred Years War Online

Authors: Desmond Seward

This may well have been how the Dauphinists saw him, and at this period they themselves were short of even moderately good commanders.

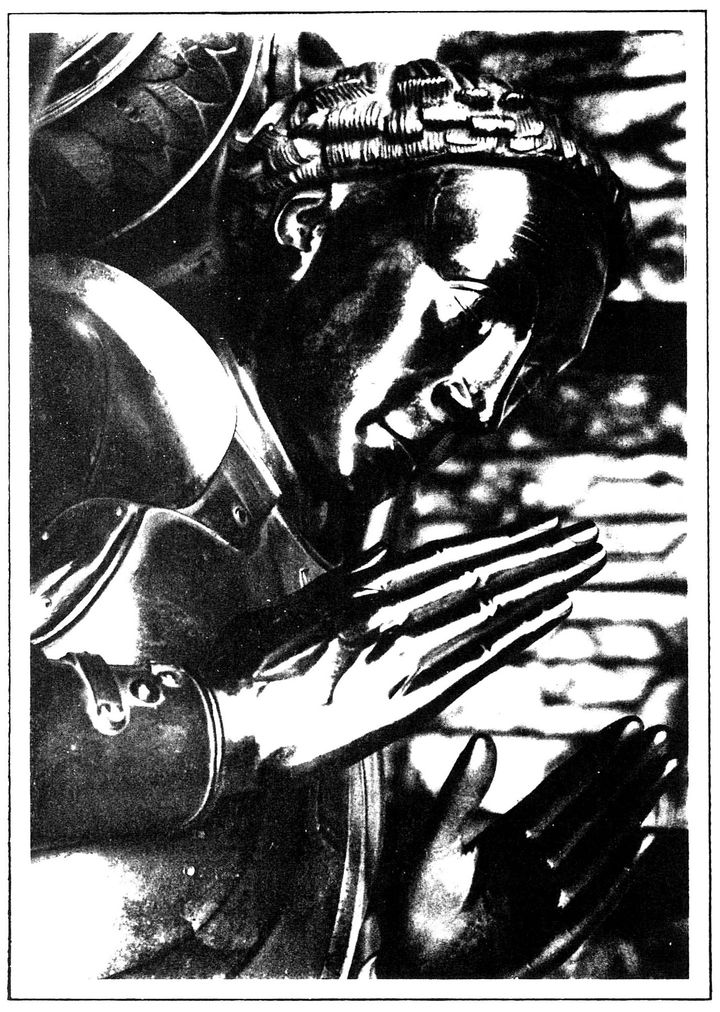

There was a third Englishman of the same calibre as Bedford and Salisbury, Richard Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick and Count of Aumale. However although undoubtedly as capable, despite long and conscientious service in France he achieved less. Warwick’s fascination is that he is almost the only English commander in the Hundred Years War (other than a monarch) of whom a probable natural likeness has survived. His effigy at Warwick shows a fine-boned face, fastidious yet powerful and unmistakably patrician, with an expression which is both graceful and arrogant. Even his hands have the same haughty elegance. Moreover we know a good deal about his life from the account written a generation later by the antiquarian John Rous. Born in 1382, Warwick fought and routed Owain Glyndwr when he was only twenty. In 1408 he went on a remarkable pilgrimage to Jerusalem, and en route was the guest of Charles VI at Paris and of the Doge at Venice, besides fighting a triumphant tournament with Pandolfo Malatesta at Verona. On the way home he visited Poland and the Teutonic Knights in Prussia and Germany. After taking part at the siege of Harfleur in 1415 he received Emperor Sigismund at Calais, when he declined to accept the gift of a sword for King Henry, suggesting that the Emperor should present it in person. Warwick played an important part in the conquest of Normandy and in the negotiations which led to the Treaty of Troyes. At various times Captain of Calais, Rouen, Meaux and Beauvais, ‘Captain and Lieutenant General of the King and the Regent in the Field’ in 1426—1427, and a member of the Council of Regency in England, he was a pillar of the Anglo-French state. Immensely wealthy, with an income of nearly £5,000, and of ancient lineage—the Beauchamps had been Earls since 1268—he had the honour of being appointed tutor to the young Henry VI. Due to lack of space there is not much about chivalry in these pages, but its ideals were real enough, and there was no better fifteenth-century English exponent of it than Warwick. It is therefore all the more interesting that this was the man who would burn Joan of Arc.

Salisbury and Warwick could rely on an unusually gifted team, most of whom worked together for twenty years or more. They were not knights-errant like the Earl of Warwick, but professional soldiers. They included Lord Willoughby d’Eresby, Lord Talbot, Lord Scales, Sir John Fastolf, Sir Matthew Gough, Sir Thomas Rempston, Sir Thomas Kyriell and Sir William Glasdale. Brave, brutal men, they throve on a life of battles, raids and skirmishes, an existence which even when not campaigning was a routine of camp, saddle and fortress. One or two lived to be killed in the Wars of the Roses, and nearly all made fortunes.

Many took French titles, for the expropriation and hand-out of these continued, each one being accompanied by large estates (although in most cases there was a rightful holder alive in Dauphinist France). They included some of the best-known dignities in French history ; Lord Willoughby became Count of Vendôme, Lord Talbot Count of Clermont and Lord Scales Vidame of Chartres. Nor was such ennoblement confined to peers. Sir John Fastolf was made Baron of Sillé-le-Guillaume and of La Suze-sur-Sarthe, and Sir Matthew Gough Baron of Coulonces and Tillières. Such counties and baronies were eagerly sought after.

King ‘Henri’ was eventually recognized by all France north of the Loire, save for isolated Dauphinist enclaves. A good deal of this was controlled by the Duke of Burgundy —he occupied most of Champagne—while Brittany was independent under Duke John V. At its widest extent the territory directly under English rule consisted of Normandy (with the

Pays de Conquête—the

rest of the Seine valley—and Maine and Anjou), Paris and the Ile de France, some of Champagne and Picardy, and of course the Pas de Calais and Guyenne. The Dauphin reigned over the rest, after a fashion. His Council was at Poitiers but as his court was sometimes at Bourges he was contemptuously called ‘The King of Bourges’. In practice he was seldom there, moving from château to château.

Pays de Conquête—the

rest of the Seine valley—and Maine and Anjou), Paris and the Ile de France, some of Champagne and Picardy, and of course the Pas de Calais and Guyenne. The Dauphin reigned over the rest, after a fashion. His Council was at Poitiers but as his court was sometimes at Bourges he was contemptuously called ‘The King of Bourges’. In practice he was seldom there, moving from château to château.

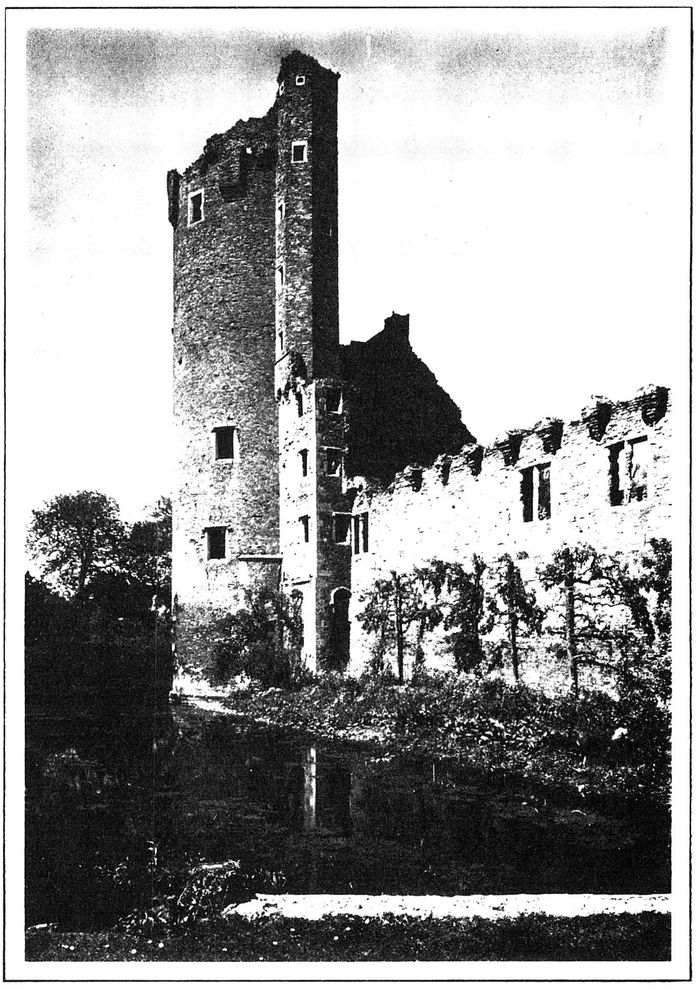

Caister Castle, Norfolk—in its day furnished with splendour and luxury. Built by the soldier Sir John Fastolf, originally an esquire of £46 a year, who out of the profits of war in France and their careful investment had increased his income to £1,450 a year when he died in 1459.

The man who burnt Joan of Area Richard Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick and Count of Aumale, Captain of Rouen and many other French cities (1382—1439). He was finally Lieutenant-General of France from 1437—1439

The Anglo-French realm was kept entirely separate from England and governed through long-standing institutions by Frenchmen supervised by a few senior English officials. Despite the promises made at Troyes, Normandy (with the Pays de

Conquête,

and Maine and Anjou) was administered as a state apart—the Regent being determined to turn the duchy into a Lancastrian bastion—by a council at Rouen. Though the

baillis

were always Englishmen, almost all other civil officials were natives. Bedford did his best to make English rule popular with the Normans, encouraging trade, founding a university at Caen and issuing an excellent gold coinage in his nephew’s name—the

salut.

Conquête,

and Maine and Anjou) was administered as a state apart—the Regent being determined to turn the duchy into a Lancastrian bastion—by a council at Rouen. Though the

baillis

were always Englishmen, almost all other civil officials were natives. Bedford did his best to make English rule popular with the Normans, encouraging trade, founding a university at Caen and issuing an excellent gold coinage in his nephew’s name—the

salut.

The government of Paris was quite distinct. It possessed what has been described as the beginnings of ‘an Anglo-French secretariat’, for even before an English garrison had been installed, its bureaucracy had been purged of Dauphinist symphathizers and had no qualms at co-operating with the English. Some of these Burgundian officials worked in Rouen and in London as well as in Paris. When at the capital Bedford lived at the Hôtel des Tournelles, where he gave splendid parties for the Parisians like that in June 1428 for 8,000 guests; the Bourgeois says that the nobles and clergy were invited ‘then the doctors of every science and the lawyers from the

Parlement,

the Provost of Paris and the officials from the Châtelet, then the Provost of the Merchants, the Aldermen, the Bourgeois and even the commons’. The Regent was particularly careful to keep on amiable terms with the University, the

Parlement

and all the civic dignitaries.

Parlement,

the Provost of Paris and the officials from the Châtelet, then the Provost of the Merchants, the Aldermen, the Bourgeois and even the commons’. The Regent was particularly careful to keep on amiable terms with the University, the

Parlement

and all the civic dignitaries.

Yet however anxious he may have been to make Plantagenet rule popular, Bedford none the less tried to force his subjects to contribute to the war effort. Paris had to endure ferocious taxation, but the Normans suffered most—‘Normandy was indeed, in the full sense of the term, the milch cow of Lancastrian rule,’ is Perroy’s comment. Besides the subsidies granted by the Estates there was a gabelle, a

quatrième

on wine and cider, and a sales tax on all goods. In addition the guet was levied, a hearth tax to pay the troops. During crises such as the great campaign in 1428, even more was demanded. The peasants also had to suffer from the English garrisons—foraging, looting and kidnapping for ransom, and the

pâtis

or protection racket. The same sort of demands, official and unofficial, were made in Anjou and Maine and in the Ile de France. As time passed and the English became increasingly desperate for money, both the taxation and the plundering grew still more oppressive.

quatrième

on wine and cider, and a sales tax on all goods. In addition the guet was levied, a hearth tax to pay the troops. During crises such as the great campaign in 1428, even more was demanded. The peasants also had to suffer from the English garrisons—foraging, looting and kidnapping for ransom, and the

pâtis

or protection racket. The same sort of demands, official and unofficial, were made in Anjou and Maine and in the Ile de France. As time passed and the English became increasingly desperate for money, both the taxation and the plundering grew still more oppressive.

Life was made almost intolerable for the peasants by English freebooters and by

écorcheurs.

One of the most notorious of the former was Richard Venables, who came to Normandy in 1428 with only three men-at-arms and a dozen archers but who soon collected an army of deserters and set himself up in the fortified Cistercian monastery of Savigny, from where he rode out to rob and murder. His bloodiest exploit was at Vicques near Falaise where he massacred an entire village. Venables’s band was only one among many. The

écorcheurs,

or flayers, were gangs of highwaymen who were the heirs of the

routiers :

they took their name from their custom of stripping victims to the skin and even flaying them alive. Bedford did his best to defend the unfortunate country people. In Normandy he gave them arms and tried to make them practise archery on Sundays. In Maine he issued certificates of protection under his own seal (for a household or for a parish as a whole) together with travel permits and safe conducts, though all these had to be paid for in hard cash.

écorcheurs.

One of the most notorious of the former was Richard Venables, who came to Normandy in 1428 with only three men-at-arms and a dozen archers but who soon collected an army of deserters and set himself up in the fortified Cistercian monastery of Savigny, from where he rode out to rob and murder. His bloodiest exploit was at Vicques near Falaise where he massacred an entire village. Venables’s band was only one among many. The

écorcheurs,

or flayers, were gangs of highwaymen who were the heirs of the

routiers :

they took their name from their custom of stripping victims to the skin and even flaying them alive. Bedford did his best to defend the unfortunate country people. In Normandy he gave them arms and tried to make them practise archery on Sundays. In Maine he issued certificates of protection under his own seal (for a household or for a parish as a whole) together with travel permits and safe conducts, though all these had to be paid for in hard cash.

But despite Bedford’s heroic endeavours, Lancastrian France eventually became a wilderness laid waste by its garrisons, by deserters, by

écorcheurs

and by Dauphinist raiders. At the end of the 1420s the revenues from Normandy began to fall drastically. It was painfully obvious that the conquered territories were not going to pay for the War.

écorcheurs

and by Dauphinist raiders. At the end of the 1420s the revenues from Normandy began to fall drastically. It was painfully obvious that the conquered territories were not going to pay for the War.

From the very beginning only Burgundian support made it possible for the dual monarchy to function at all. ‘Burgundian’ in this context did not of course mean someone from Burgundy but was the name of a political allegiance —those Frenchmen who preferred to be governed by the Duke of Burgundy or his allies rather than by Dauphinists. Many now genuinely believed that a strong English régime would bring peace and put an end to the bloody civil war of the last dozen years ; moreover they also thought that—on past form—the English were bound to win a war with the Dauphinists (in much the same way that Pétainists estimated German chances in 1940). Remembering the Armagnac terror, every Parisian dreaded the massacres which would surely follow the return of the Dauphin, a fear echoed in every town in Anglo-Burgundian France. Even before the Lancastrian occupation, the Bourgeois of Paris thought it better to be a prisoner of the English than of the Dauphin ‘and those people who call themselves Armagnacs’. Later, describing Armagnac campaigns, the Bourgeois said they perpetrated crimes worse ‘than any man or demon could commit’; this rational and decent observer, probably a Canon of Notre-Dame, uses such terms as ‘worse than Saracens’ or ‘unchained devils’. Unfortunately the English position depended on more than fear of Armagnacs.

The most dangerous threat was the difficult nature of Duke Philip. Splendid in appearance, he was arrogant and violent-tempered-in his rages his face took on a bluish hue —and extremely touchy. Still more disconcerting, this pillar of chivalry was a notorious liar ; little reliance could be placed on his word, for he was whimsical and changeable. Although intent on strengthening his power in his own domains and on acquiring more territory in the Low Countries, and though bored by French politics, the Duke was proud of his Valois blood and could never really accept a Plantagenet France. As the memory of his father’s murder faded he was increasingly ready to flirt with the Dauphinists. He showed his hand by declining to become a Knight of the Garter and thus refusing to swear an oath of loyalty to English brethren. Bedford strove desperately to keep on good terms with him.

In April 1423 the Dukes of Bedford, Burgundy and Brittany met at Amiens to sign a treaty in which each swore ‘brotherhood and union as long as we live’ and tacitly pledged himself to work for the Dauphin’s final overthrow, though entering into no military commitment. Burgundy and Brittany signed with reservations, later making a secret treaty in which they promised to remain friends should either of them ally with the Dauphin. In May the Regent married Philip’s sister, Anne of Burgundy, a purely political match which became a noticeably happy marriage—although she was ‘as plain as an owl’. A contemporary commented: ‘My Lord the Regent loves Madame Regent so well that always he brings her with him to Paris and everywhere else.’ Intelligent, gay and devout, Anne tried hard to preserve the alliance between her husband and her brother.

If there was no proper strategic co-operation between the English and the Burgundians, a good working military relationship often existed in the field. This was very much in evidence throughout 1423. An allied army took Le Crotoy, while a similar force under the Duke of Norfolk and Jean de Luxembourg routed the Dauphinist Poton de Xaintrailles. Everywhere English and Burgundians joined in raids and skirmishes. In the south-west however, the English and Guyennois had to fight by themselves, raiding and counter-raiding on the borders of Guyenne, over into the Saintonge and Poitou and into the Limousin and Périgord ; they had to repel Dauphinist attacks on La Réole and in the Entre-deux-mers.

Other books

Adela's Prairie Suitor (The Annex Mail-Order Brides Book 1) by Elaine Manders

Texas Funeral by Batcher, Jack

The Untamed Mackenzie by Jennifer Ashley

Darkest Love by Melody Tweedy

Two Against the Odds by Joan Kilby

Jellied Eels and Zeppelins by Sue Taylor

Admissions by Jennifer Sowle

Silver City Massacre by Charles G West

The Body in Bodega Bay by Betsy Draine

One Wild Night by Jessie Evans