The Hundred Years War (21 page)

Read The Hundred Years War Online

Authors: Desmond Seward

Next morning the English trudged on through a torrential downpour which was blown into their eyes by a driving wind. For several days they continued their march without serious incident, covering as much as eighteen miles a day, all of it beneath the unrelenting rain. On 24 October the Duke of York’s scouts saw through the drizzle the French army advancing on their right like ‘an innumerable host of locusts’, in a direction which meant that they would soon intercept the English line of advance. Henry took up battle positions along a ridge, and the French, who had now sighted their quarry, also took up positions. The enemy appeared to have learnt a good deal since Crécy and would not attack such a strong position so late in the day. Nonetheless, they continued to advance so that by nightfall they had effectively blocked the English road to Calais.

All hope of retreat had gone. The English plodded on up the muddy road to the little village of Maisoncelles. The King himself slept near the village of Blangy, no doubt under cover. His men had to sleep in the open beneath the drenching rain, the luckier finding some wretched shelter beneath trees or bushes. There were now less than 6,000 of them—about 5,000 archers and perhaps 800 men-at-arms. Many were still suffering from dysentery while even the strongest had been weakened not only by their miserable march through the wet but by lack of nourishment, being reduced to a little cold food supplemented by nuts and raw vegetables taken from the fields. They seem to have had few fires that night. The archers must have been especially tired as unlike the men-at-arms many of them had no horses and had to carry their weapons, which included quivers holding fifty arrows and wooden stakes for defence. All were terrified by the enormous size of the force facing them. Even Henry was shaken and released his prisoners, sending a message to the enemy commanders in which he offered to return Harfleur and pay for any damage he had done if he were allowed safe passage to Calais ; but the French terms were too steep —renunciation of his claims in France to everything save Guyenne.

The King ordered his troops to be silent during the night, threatening knights with the confiscation of horse and armour, lower ranks with the amputation of an ear. Understandably an eerie quiet prevailed throughout the English camp, interrupted only by armourers hammering and sharpening, and by the whispers of men being shriven by their chaplains. The French took it for a good sign, believing that the English thought themselves already beaten. Many of the latter must surely have felt like this, hearing all the confident noise and bustle from the enemy camp where there were between 40,000 and 50,000 men-at-arms. Meanwhile Henry sent out scouts to examine the ground.

By dawn both armies were preparing for battle. The rain had at last stopped, but the ploughed land underfoot was nothing but slippery mud—in some places knee-deep. The King drew up his bedraggled troops in a field of newly sown wheat (in a formation similar to that used by Edward III at Crécy). He himself commanded the centre, the Duke of York the right, and Lord Camoys KG the left ; there were three ‘battles’ of dismounted men-at-arms, the gaps between the battles being filled by projecting wedges of archers ; while the main body of bowmen formed horns on the wings, standing slightly forward so they could shoot inwards if the French attacked the centre. There was no reserve, but at least the English flanks were protected by woods.

The French position, directly north of the English, also lay between these two small woods, one of which was close to the little village of Tramecourt, the other to that of Agincourt. It was a badly chosen position ; not only was it too narrow but the ploughed fields in front had been churned up by horses’ hooves. The actual formation consisted of two long lines of dismounted men-at-arms carrying sawn-off lances, while behind them and on the wings were the remaining men-at-arms who were still on horseback. The artillery was on the wings too, but was hampered by the confusion among the men-at-arms who found their heavy armour a terrible hindrance on the sodden ground. Marshal Boucicault and the Constable d’Albret were nominally in command, though in practice there was no proper command-structure or leadership of any sort. However, for the moment the French had the sense to wait for the English to attack.

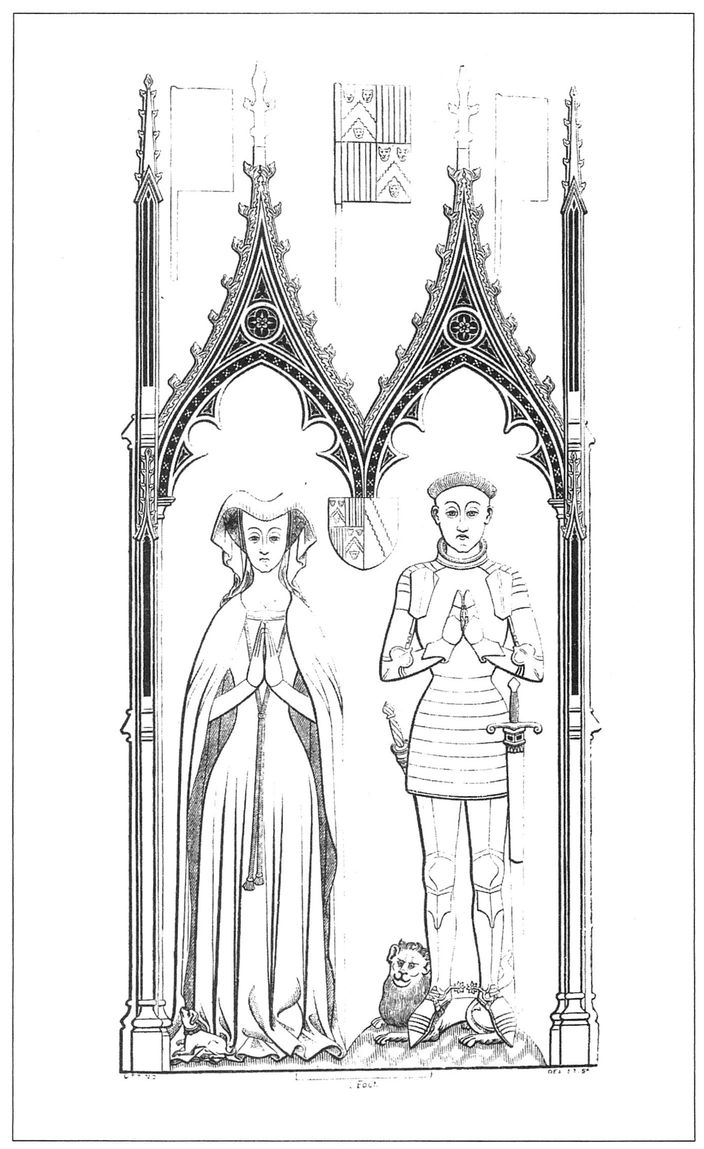

Sir Hugh Halsham, who fought at Agincourt in Lord Arundel’s retinue; and his wife, Joyce Culpeper. Brass of 1441 at West Grinstead, Sussex.

King Henry heard three Masses and took communion before addressing his men. He told them ‘he was come into France to recover his lawful inheritance’, and that the French had promised to cut three fingers off every English archer’s right hand so ‘they might never presume again to shoot at man or horse’. Although he rode only a little grey pony he must have been an impressive figure, in his gold-plated helmet with its golden crown of pearls, rubies and sapphires. His army shouted to him, ‘Sir, we pray God give you a good life and the victory over your enemies.’ Undoubtedly they admired him and believed in his genius, and were confident that he would rescue them from this terrifying situation.

The King must have prayed for the French to attack so that he could use his bowmen. But for several hours the French stayed calmly in their positions. At about nine o‘clock Henry therefore told Sir Thomas Erpingham, ‘a grey-headed old knight‘, to take the archers on the wings forward within range of the enemy. When this had been done the King gave the order for the rest of his little army to move forward—‘Banners advance ! In the name of Jesus, Mary and St George !’ After making the sign of the Cross and kissing the earth, the English marched forward solidly over the dirty ground in good order. Most of the bowmen ‘had no armour but were only wearing doublets, their hose rolled up to their knees, with hatchets and axes or in some cases large swords hanging from their belts ; some of them went barefoot and had nothing on their heads, while others wore caps of boiled leather’. They halted at a little less than 300 yards from the enemy and, after sticking their pointed stakes in the ground in front of them, began to shoot. The French put their heads down, the English arrows falling so thick and fast that no one dared look up. In desperation the mounted French men-at-arms on the wings charged the archers. As always the horses suffered most from the arrows, becoming unmanageable or bolting, while those that did reach the English lines were impaled on the six-foot stakes which were set a horse’s breast high.

The first line of the enemy’s dismounted men-at-arms then formed themselves into a column, hoping fewer would be hit by arrows, and toiled slowly forward towards the English through the thick mud which had been churned up still further by the horses. The English on the wings shot steadily into the sides of the column, inflicting many casualties, their arrows making a terrifying hiss and clatter. When the French at last reached the English lines they were in no coherent formation and too tightly packed, while the deep mud had slowed them almost to a halt. This combination of disorder and immobility would cost them the battle.

Nevertheless at the first impact the French threw back the front line of English men-at-arms at Henry’s centre, almost knocking them off their feet. The King quickly ordered his archers to drop their bows and go to the men-at-arms’ assistance, whereupon seizing ‘swords, hatchets, mallets, axes, falcon-beaks and other weapons’ they hurled themselves on the enemy. The liquid mud of the battlefield gave the advantage to the bowmen who were able to dance round the ponderous Frenchmen, whom they stabbed through the joints of their armour or bowled over. Some of the latter lay writhing on their backs like capsized crabs until their visors were knocked open and daggers thrust into their faces ; most drowned in the mud or died of suffocation, pressed down by the bodies of their comrades on top of them.

The enemy’s second line of men-at-arms, also in column, came on in equal disorder to meet with the same reception from the English, who were now standing on piles of French corpses. Their leader, the Duke of Alençon, fought like a lion, striking down the Duke of Gloucester and beating the King to his knees—he actually hacked a

fleuret

from his crown—but was eventually overwhelmed. He surrendered to Henry, taking off his helmet, but was at once cut down with an axe by a berserk English knight. The Duke of Brabant, who had arrived late without his surcoat and donned a herald’s tabard instead, was disarmed ; not being recognized, he had his throat cut. After only half an hour both the first and the second French columns had been annihilated; in some places the heaped bodies were higher than a man’s head. The English turned them over, searching for loot and any valuable prisoners still alive, who were sent to the rear. Henry and his commanders soon made the men return to their positions. There was still a threat from the remaining French troops.

fleuret

from his crown—but was eventually overwhelmed. He surrendered to Henry, taking off his helmet, but was at once cut down with an axe by a berserk English knight. The Duke of Brabant, who had arrived late without his surcoat and donned a herald’s tabard instead, was disarmed ; not being recognized, he had his throat cut. After only half an hour both the first and the second French columns had been annihilated; in some places the heaped bodies were higher than a man’s head. The English turned them over, searching for loot and any valuable prisoners still alive, who were sent to the rear. Henry and his commanders soon made the men return to their positions. There was still a threat from the remaining French troops.

While the King was waiting for a third enemy assault, a cry went up that the French had received reinforcements. At the same moment he learnt that hundreds of peasants were attacking his baggage. Henry immediately ordered the execution of all prisoners save the most distinguished. The men guarding them were most reluctant to lose so many valuable ransoms, so the King detailed 200 archers to do the job, the Frenchmen being (in the words of a Tudor historian) ‘sticked with daggers, brained with poleaxes, slain with mauls’—to make quite sure, they were also ‘paunched in fell and cruel wise’. One group was burnt to death by setting fire to the hut where they were confined. English writers attempt to whitewash this piece of

Schrechlichkeit

by Henry, usually with reference to ‘the standards of the day’, but in fact by medieval criteria it was a particularly nasty atrocity to murder unarmed noblemen who had surrendered in the confident expectation of being ransomed.

Schrechlichkeit

by Henry, usually with reference to ‘the standards of the day’, but in fact by medieval criteria it was a particularly nasty atrocity to murder unarmed noblemen who had surrendered in the confident expectation of being ransomed.

In fact the third enemy assault never materialized. Although they still outnumbered the English, the remaining French men-at-arms were so horrified by the butchery in front of them that they refused to attack and rode off the battlefield. In less than four hours the English, against all expectation, had defeated an army many times larger. The French had lost about 10,000 men, among them such great lords as the Dukes of Alençon, Bar and Brabant, the Constable d‘Albret (though his fellow commander Marshal Boucicault survived as a prisoner), the Count of Nevers with six other counts, 120 barons and 1,500 knights. The English had lost perhaps 300 men, the only persons of note among them being Henry’s cousin, the fat Duke of York—he had fallen over and been suffocated by bodies falling on top of him—and the Earl of Suffolk together with half a dozen knights. Many were badly wounded however, notably Henry’s brother the Duke of Gloucester—‘In the hammes’.

The chivalry of the Black Prince was not for King Henry. That night his high-ranking prisoners had to wait on him at table. The troops took another hopeful look at the French casualties still lying all over the field ; anyone who was rich and could walk was rounded up, but the poor and the badly wounded had their throats slit. Next day, laden with plunder from the corpses, the English recommenced their march to Calais, dragging 1,500 prisoners along with them. The rain began again. Wetter and hungrier than ever, the little army reached Calais on 29 October. Here, although the King was fêted rapturously, his men were hardly treated as conquering heroes. Some were even refused entry, while the Calais people charged them such exorbitant prices for food and drink that they were soon cheated out of their loot and rich captives. (Henry kept the great prisoners for himself—he wanted every penny of their ransoms.)

The troops were too exhausted for any further campaigning, so in mid-November the King sailed for England. On 23 November he entered London to receive an ecstatic welcome. There were pageants and tableaux, orations, dancing in the streets and carols—including the famous Agincourt Carol—while the drinking fountains ran with wine. The euphoria was such that Henry was to have little trouble in raising fresh loans for more campaigns during the next few years. Meanwhile he gave thanks at St Paul’s.

In reality, as Perroy emphasizes, the Agincourt campaign decided nothing—It was just another

chevauchée.

Nevertheless it is hardly surprising that Henry was determined to follow it up. He made the most of Harfleur, the sole tangible gain, every inducement including free housing being offered to merchants and artisans in the hope that they would settle there and make it a Norman Calais.

chevauchée.

Nevertheless it is hardly surprising that Henry was determined to follow it up. He made the most of Harfleur, the sole tangible gain, every inducement including free housing being offered to merchants and artisans in the hope that they would settle there and make it a Norman Calais.

Other books

The Lost Years by E.V Thompson

The Sword and the Sorcerer by Norman Winski

Green Fields (Book 4): Extinction by Lecter, Adrienne

Healthy Bread in Five Minutes a Day: 100 New Recipes Featuring Whole Grains, Fruits, Vegetables, and Gluten-Free Ingredients by Francois, Zoe, Hertzberg MD, Jeff

A Summer Hope (Summer Dream Book 3) by Bianca Vix

Unremembered by Jessica Brody

Lovers & Liars by Joachim, Jean C.

Mastered by Her Mates (Interstellar Bride Book 0) by Grace Goodwin

Tell Me Your Dreams by Sidney Sheldon

Bad Science by Ben Goldacre