The Hundred Years War (29 page)

Read The Hundred Years War Online

Authors: Desmond Seward

The Maid began to campaign again in October. She took Saint-Pierre-le-Moutier on the upper Loire, but failed to capture the nearby town of La Charité. She was not always merciful; on at least one occasion she ordered the beheading of an enemy commander who had been taken prisoner. In May 1430 she moved to Compiègne. During a skirmish outside the town on 24 May she was plucked from her charger by a Burgundian soldier. Monstrelet noted that the English and the Burgundians ‘were much more excited than if they had captured 500 fighting men, for they had never been so afraid of any captain or commander in war as they had been of the Maid’. In November Joan was handed over to the English. At Rouen she received rough treatment from Warwick’s soldiers—they tried to rape her, and Lord Stafford actually drew a dagger on the girl.

Joan’s trial began on 21 February the following year after a lengthy and unscrupulous investigation by canon lawyers. The prosecution’s case (no doubt with rumours about Charles VII in mind) was that this ‘false soothsayer’ had rejected the authority of the Church in claiming a personal revelation from God, in prophesying, in signing her letters with the names of Christ and the Virgin, and in asserting that she was assured of salvation. These not unreasonable accusations were accompanied by lesser charges, such as her sexual perversity in wearing male dress—‘a thing displeasing and abominable to God’—and her insistence that the saints spoke French and not English. The entire justification of the Lancastrian right to the French throne was at stake : she had to be found guilty. After much bullying, trickery and misrepresentation the lawyers trapped her, and on 30 May 1431 she was burnt by Warwick’s soldiers in the market-place at Rouen as a relapsed heretic. She died quickly and the executioner pulled the charred corpse out of the fire so that people could see that it was that of a woman. She was only nineteen.

King Charles had made no attempt to save her. However, twenty years later he ordered an enquiry, and eventually the Papacy annulled the sentence. She was not canonized until 1920. For at least two centuries the English remained convinced that she was a witch; as Bedford wrote, in a letter to the Duke of Burgundy, she had ‘turned away the hearts of many men and women from the truth, and turned them towards fables and lies’.

Joan’s execution made little stir. However, since then the sorceress maid from Domrémy has aroused far greater interest than in her own short day. In the 1460s François Villon referred to Joan among other of the world’s famous women :

and from Voltaire to Shaw to our own day, a surprising range of gifted writers have been fascinated by this Catholic saint. In France some traditionalist Frenchmen still consider veneration of their

petite pucelle

to be one of the hallmarks of a true patriot. In a different way she inspires no less devotion in England and America. Nevertheless she failed in her mission.

Et Jehanne la bonne Lorraine

Qu’Englois brulèrent à Rouen

Qu’Englois brulèrent à Rouen

petite pucelle

to be one of the hallmarks of a true patriot. In a different way she inspires no less devotion in England and America. Nevertheless she failed in her mission.

The Regent saved the dual monarchy through sheer determination. It was a very near thing, for although Charles was incapable of exploiting the situation, towns all over northern France had opened their gates to his supporters ; English Champagne was lost and Maine looked like going the same way. There were even risings in Normandy, where between 1429 and 1431 Bedford had his headquarters, in Rouen at a modest

hôtel

ironically named

JoyeuxRepos.

English troops deserted in large numbers, some making for the Channel ports, in the hope of finding a passage to England, while others became bandits. Luckily, Philip of Burgundy was impressed by the fact that the English had held Paris, and until he had complete control of Hainault and Holland—which he did not achieve until 1433 —he was nervous of losing the Regent’s friendship.

hôtel

ironically named

JoyeuxRepos.

English troops deserted in large numbers, some making for the Channel ports, in the hope of finding a passage to England, while others became bandits. Luckily, Philip of Burgundy was impressed by the fact that the English had held Paris, and until he had complete control of Hainault and Holland—which he did not achieve until 1433 —he was nervous of losing the Regent’s friendship.

The English had to pay heavily for such support. Between 1429 and 1431 Philip obtained £150,000 from them for his services and was owed a further £100,000. After 1431 he was paid a monthly pension of 3,000 francs (about £330). In addition in March 1430 the English ceded Champagne to him—though this was already occupied by Dauphinists—together with 50,000 gold

saluts

(Anglo-French gold crowns minted at Rouen), in return for military assistance against the Dauphinists for two months.

saluts

(Anglo-French gold crowns minted at Rouen), in return for military assistance against the Dauphinists for two months.

Slowly the Regent restored the situation. Château Gaillard was recovered in June 1430, and the English continued to regain ground everywhere throughout 1431. In March Bedford himself retook Colummiers, Gourlay-sur-Marne and Montjoy ; at the same time the Earl of Warwick annihilated a raiding force which had tried to ambush the Regent, capturing its commander Poton de Xaintrailles, together with a shepherd boy who was supposed to be Joan’s successor (he deliberately bloodied his hands and feet in imitation of St Francis’s stigmata). In October Louviers fell to Bedford, after a siege of nine months. The Duke of Burgundy was not so successful, losing territory to the Dauphinists.

The impetus generated by Joan’s revivalism had ground to a halt. The apathy of the Dauphinists is understandable enough. It was not simply because of the supine nature of the man who was the leader and the symbol of Valois France, but because more fighting meant more devastation. Basin wrote how ‘from the Loire to the Seine the peasants had been slain or put to flight’. The bishop continued : ‘We ourselves have seen the vast plains of Champagne, of the Beauce, of the Brie, of the Gâtinais, Chartres, Dreux, Maine and Perche, of the Vexin (French as well as Norman), the Beauvaisis, the Pays de Caux, from the Seine as far as Amiens and Abbeville, the countryside round Senlis, Soissons and Valois right to Laon and beyond towards Hainault absolutely deserted, uncultivated, abandoned, empty of inhabitants, covered with scrub and brambles; indeed in most of the more thickly wooded districts dense forests were growing up.’

The capital itself was in a frightful state. As a result of interrupted communications and exposed supply routes, together with harassment by brigands and peasants, many Parisians were starving, while travellers were ambushed by raiding parties lurking outside the city. At night wolves continued to prowl the streets, looking for dead bodies or children. Thousands left in despair. Now that Burgundy had relinquished his governorship Bedford could act, and on the last day of January 1431 he returned to Paris

‘en très belle compagnie’,

bringing up with him seventy barges laden with food. The Bourgeois records how Parisians said that ‘for 400 years people had never seen so much to eat’. But it was only a drop in an ocean, and the famine became even worse, the price of wheat doubling. The Parisians ‘often cursed the Duke, not only in private but in public as well, giving way to despair and ceasing to believe in his fine promises’.

‘en très belle compagnie’,

bringing up with him seventy barges laden with food. The Bourgeois records how Parisians said that ‘for 400 years people had never seen so much to eat’. But it was only a drop in an ocean, and the famine became even worse, the price of wheat doubling. The Parisians ‘often cursed the Duke, not only in private but in public as well, giving way to despair and ceasing to believe in his fine promises’.

Bedford decided to play his trump card. At the end of November the nine-year-old ‘Henri II’ arrived at Saint-Denis and on 2 December made his

joyeuse entrée

into the capital of his Kingdom of France. Yellow-haired and in cloth of gold, he rode on a white charger through the icy streets to be greeted by the Provost and the Councillors of the

Parlement

in their red satin. Although starving, the Parisians gave the King a tumultuous welcome, crying ‘Nowell’; obviously they hoped for a rich bounty from the royal largesse. On Sunday 16 December he went on foot to Notre-Dame, accompanied by citizens who sang melodiously. A huge dais had been erected in front of the choir, its steps painted sky-blue and studded with golden fleur-delys, and here Henry was anointed King of France by Cardinal Beaufort. Alas, Beaufort, who was in charge of the proceedings, ruined everything by tactlessness, ill-management and parsimony. The Bishop of Paris, whose cathedral it was, had to take a back seat, while the service was conducted according to the English Sarum rite and not the Gallican usage of France, and a silver-gilt chalice was stolen by English officers. The coronation banquet was little better than a riot. The Paris mob forced its way into the Hôtel des Tournelles ‘some to see, others to devour and others still to steal‘, and in the end the representatives of the University and the

Parlement

and the aldermen gave up trying to throw them out; those who managed to find something to eat learnt with horror that the food had been cooked the preceding Thursday, ‘which appeared very strange to Frenchmen’. Later the sick at the Hôtel-Dieu complained they had never known such a poor and meagre bounty. In the Bourgeois’s view, Paris had seen merchants’ marriages which had been ‘of more profit to the jewellers, goldsmiths and other purveyors of luxury than this coronation of a King, with all its jousts and Englishmen’. Henry left Paris the day after Christmas, without having pardoned any prisoners or abolished any taxes as was customary. ‘One heard nobody, in private or in public, commend his stay and yet no King was ever more honoured than he had been at his

joyeuse entrée

or at his consecration, especially when one considers the depopulation of Paris, the evil times and that it was full winter and how dear was food.’ Instead of making the régime popular, the coronation had merely infuriated the Parisians.

joyeuse entrée

into the capital of his Kingdom of France. Yellow-haired and in cloth of gold, he rode on a white charger through the icy streets to be greeted by the Provost and the Councillors of the

Parlement

in their red satin. Although starving, the Parisians gave the King a tumultuous welcome, crying ‘Nowell’; obviously they hoped for a rich bounty from the royal largesse. On Sunday 16 December he went on foot to Notre-Dame, accompanied by citizens who sang melodiously. A huge dais had been erected in front of the choir, its steps painted sky-blue and studded with golden fleur-delys, and here Henry was anointed King of France by Cardinal Beaufort. Alas, Beaufort, who was in charge of the proceedings, ruined everything by tactlessness, ill-management and parsimony. The Bishop of Paris, whose cathedral it was, had to take a back seat, while the service was conducted according to the English Sarum rite and not the Gallican usage of France, and a silver-gilt chalice was stolen by English officers. The coronation banquet was little better than a riot. The Paris mob forced its way into the Hôtel des Tournelles ‘some to see, others to devour and others still to steal‘, and in the end the representatives of the University and the

Parlement

and the aldermen gave up trying to throw them out; those who managed to find something to eat learnt with horror that the food had been cooked the preceding Thursday, ‘which appeared very strange to Frenchmen’. Later the sick at the Hôtel-Dieu complained they had never known such a poor and meagre bounty. In the Bourgeois’s view, Paris had seen merchants’ marriages which had been ‘of more profit to the jewellers, goldsmiths and other purveyors of luxury than this coronation of a King, with all its jousts and Englishmen’. Henry left Paris the day after Christmas, without having pardoned any prisoners or abolished any taxes as was customary. ‘One heard nobody, in private or in public, commend his stay and yet no King was ever more honoured than he had been at his

joyeuse entrée

or at his consecration, especially when one considers the depopulation of Paris, the evil times and that it was full winter and how dear was food.’ Instead of making the régime popular, the coronation had merely infuriated the Parisians.

Beaufort had now upset even Bedford. The Cardinal insisted that he must resign his Regency while the King was present. Not only was it an insult but it prevented Bedford from correcting Beaufort’s mistakes and from curbing his arrogance.

Undoubtedly Bedford was unusual among contemporary Englishmen in his genuine affection for the French. ‘For though the English ruled Paris for a very long time, I do honestly believe that there was not one of them who had any corn or oats sown or so much as a fireplace built in a house, save for the Regent, the Duke of Bedford,’ the Bourgeois informs us. ‘He was always building wherever he went; his nature was quite un-English, for he never wanted to make war on anyone, whereas in truth the English are always wanting to wage war on their neighbours without cause. Which is why they all die an evil death.’ The Bourgeois was not the only Frenchman to respect the Regent. Basin admits that Normandy was better cultivated and more highly populated than the rest of northern France because of Bedford, who was ‘courageous, humane and just’. He adds that the Regent ‘was very fond of those French lords who obeyed him and took care to reward them according to their deserts. As long as he lived the Normans and the Frenchmen in this part of the realm had a great liking for him.’

In 1432 the English position began to deteriorate noticeably. On the night of 3 February a force of 120 Dauphinists scaled the walls of the

Grosse Tour

of the citadel at Rouen with ladders let down by a traitor and seized the great fortress. Though the Rouennais stayed loyal and within a fortnight the enemy surrendered (to be beheaded), it was nonetheless a serious blow to English prestige. In March, on the eve of Palm Sunday, some Dauphinists entered Chartres hidden in provision wagons and took the city after a fierce battle in the streets ; the English lost an important source of supplies for Paris.

Grosse Tour

of the citadel at Rouen with ladders let down by a traitor and seized the great fortress. Though the Rouennais stayed loyal and within a fortnight the enemy surrendered (to be beheaded), it was nonetheless a serious blow to English prestige. In March, on the eve of Palm Sunday, some Dauphinists entered Chartres hidden in provision wagons and took the city after a fierce battle in the streets ; the English lost an important source of supplies for Paris.

In May, anxious to regain the initiative, the Regent laid siege to Lagny, a fortress which commanded the Marne and whose garrison was continually ambushing convoys on their way to Paris. The town was strongly fortified, guarded on two sides by the Marne, so Bedford blockaded it. A relief army under the Bastard of Orleans and the Castilian mercenary Rodrigo de Villandrando arrived on 9 August; no doubt the Bastard hoped to use the tactics he had employed at Montargis five years earlier.

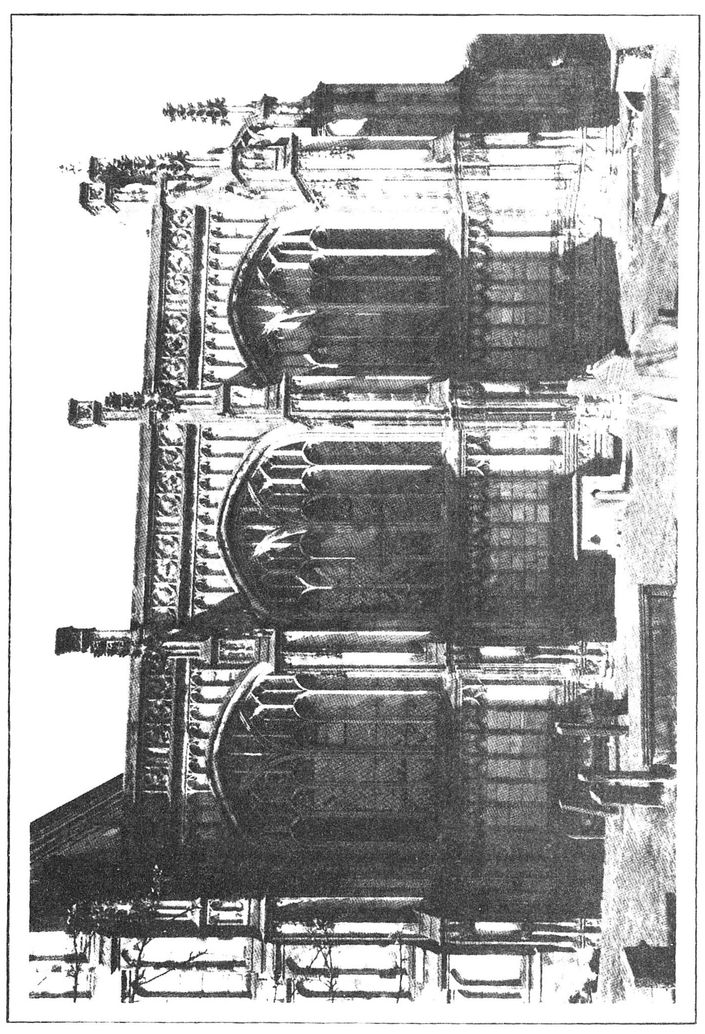

The Beauchamp chapel at Warwick, built by Earl Richard from a fortune which owed much to the French wars.

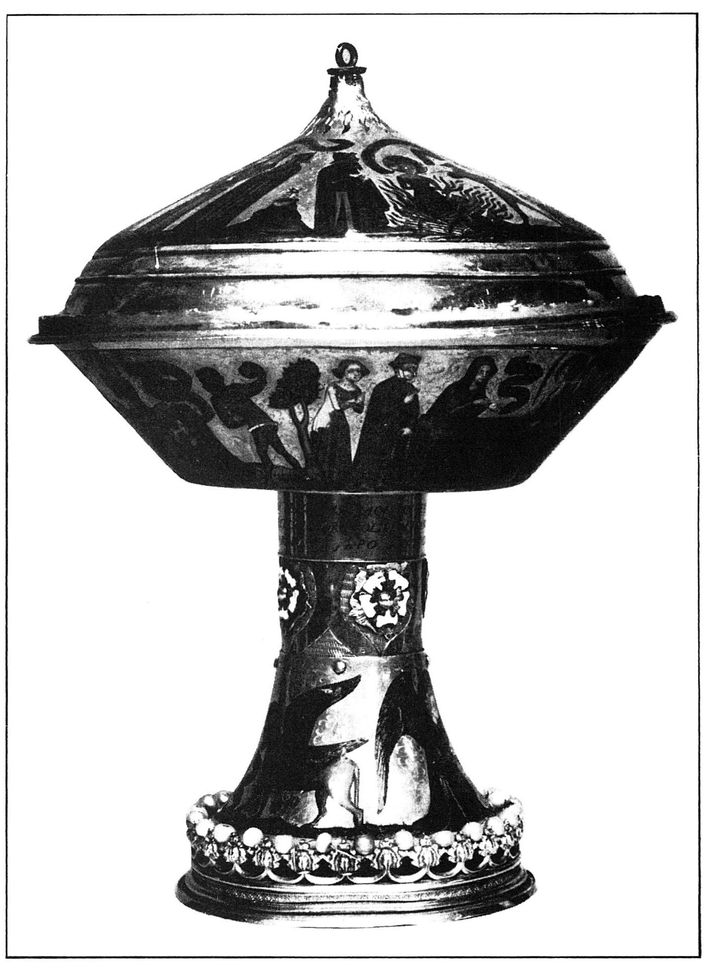

Royal plunder. The Cup of the Kings of France and England, made for Charles V

c.

1380, was in Bedford’s hands by the 1430s and was later taken to England.

c.

1380, was in Bedford’s hands by the 1430s and was later taken to England.

On 10August, a day of blazing heat, the Dauphinists tried to fight their way into Lagny and the besiegers tried to stop them. The struggle centred round a redoubt which defended the west gate; the English left wing captured it, but when their right wing was routed the Bastard attacked them and the townsmen joined in, the redoubt being retaken by the enemy. The Regent led another ferocious assault on the redoubt to stop Dauphinist wagons entering the city, and the fight surged backwards and forwards. At 4 o’clock Bedford reluctantly gave the order to disengage; the confused, untidy battle had lasted eight hours, several of his troops had died from heat-stroke and every man-at-arms, including himself, was exhausted—dehydrated, choked by dust, blinded by sweat, stunned and deafened by blows. (It is probable that Bedford’s exertions damaged his health permanently.) He had lost only 300 men but had suffered a moral defeat. He was further discouraged by a sudden change in the weather which brought heavy rain and caused the Marne to flood. When the Bastard made a feint as if to march on Paris, Bedford decided he had had enough and on 13 August raised the siege, abandoning his artillery.

Other books

Ruin by Rachel Van Dyken

Lost in His Arms by Carla Cassidy

The Right Time by Susan X Meagher

Elvis Has Left the Building by Charity Tahmaseb

Snapped by Kendra Little

Prime Target by Hugh Miller

Seven Into the Bleak by Matthew Iden

Killer Show: The Station Nightclub Fire by John Barylick

La aventura de la Reconquista by Juan Antonio Cebrián

The Seal of Solomon by Rick Yancey